Three Days, Three Legendary Japanese Views

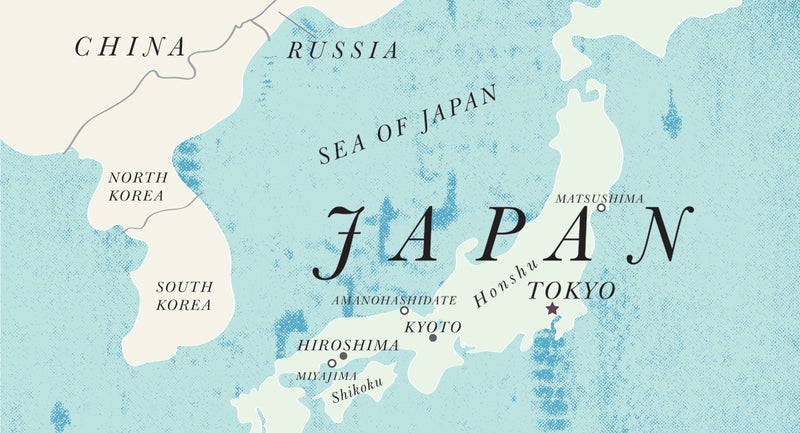

Is there such a thing as the greatest vista on earth? The Japanese think so, and they've got the breathtaking Three Scenic Views, a trio of iconic landscapes that stand above the rest. One writer takes them all in on a breakneck tour.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

The Japanese enjoy a culture of consensus. All things touristed, in particular, take their place in a hierarchy. This is convenient for travelers: the country is organized for best-of consumption. In the three years that my younger brother, Micah, lived there, we joined Japanese tourists in staying on not just the beaten track but the ranked one. We visited the Third Most Famous Original Flatland Castle and the Second Most Famous Garden, as well as the Second Most Famous Large Buddha and the First Most Famous Ancient Hot Spring. There’s even a list of the Three Most Poisonous Creatures. We stayed away from those.

The original triumvirate is the Three Scenic Views, first identified as such by a Confucian scholar in 1643; all subsequent rankings have followed that medieval lead. They are exactly what they sound like. , in western Japan, near Hiroshima, is a shrine; , north of Kyoto, is a land bridge; the third, in northern Japan, near Sendai, overlooks . Together they are not the Three Famous Places, or even exactly the Three Famous Sights. A Famous Sight is something you might behold alone. A Scenic View is something you expect to share—horizontally, with other visitors, and vertically, with the history of other viewers. Its tracks aren’t just beaten but painted and engraved and emblazoned on ancient woodcuts and postcards and T-shirts.

Most Japanese seem pretty content to admire just one of the top-flight castles or hot springs, but many of them try to visit all three of the Scenic Views at least once in their lifetimes. Micah and I always planned to see them, but suddenly time was short. After five years in Asia on an expat contract from an American tech company, Micah had just got married, and soon he and his wife, Sydnie, would be returning stateside. I had just got engaged. For so long we’d had such easy access to adventure—any visit to Micah was, by dint of his distance, effortlessly magnificent—and now the prospect of our shared future looked to be narrowing. A few weeks before the move, he called me up.

“Wanna come once more? Might be our last chance to take in those views.” There wasn’t much time, but we had developed ruthlessly efficient strategies for travel.

“We could do all three in three days,” he said.

Though the Three Views are on the main island, , they’re hundreds of miles apart. Doing them all in three days was a foolhardy proposition.

“You’re on,” I said.

Itsukushima Shrine, more popularly known as , for the island where it stands, is the most visited of the Three Scenic Views and the only one generally known to foreigners. Thousands of tourists come each year. One of the signal images of Japanese guidebooks is its bright red torii, the Shinto gate that separates the sacred shrine from the profane world. The gate rises from the protected Seto Inland Sea, which separates three of the four main islands of Japan. We left Tokyo on a bullet train before dawn, passed around sunup, changed trains three times, and by early afternoon were on the eight-minute ferry across the to Miyajima. We gathered with a few dozen Japanese tourists along the starboard railing, and Micah tried to ferret some meaning from the recorded Japanese-language narration, which unspooled robotically over a background of electronic music. The red gate was a speck of ember against the dark green haunches of the wooded island.

“Um, they’re saying something about 12 meters, and maybe something about 20 meters, and something about 6 meters,” Micah reported.

“Wonderfully illuminating,” I replied. “Thanks.”

“It’s very important to know the precise dimensions.” Micah was joking, but I think he did feel a little protective of the Japanese tendency to quantify.

The boat swung around to take in a close-up view of the gate. It was low tide, the only time when tourists can approach the base of the beached structure. Masses of visitors milled around on the dark wet sand. With the water withdrawn into the sea, the gate looked naked, stripped of the illusion of flotation it maintains on countless postcards.

“It seems, uh,” I coughed, “less impressive than I might have imagined.”

Micah, who had visited once before with his wife, was relieved. “Totally! We thought so, too. But don’t worry, wait until we get to the top of the mountain.” He pointed up and to the west, into the setting sun, where , one of Japan’s most sacred peaks, rose 1,755 feet above the gate.

[quote]A scenic view is something you expect to share—horizontally, with other viewers, and vertically, with the history of other viewers. Its tracks aren't just beaten but painted and engraved and emblazoned on ancient woodcuts and postcards and T-shirts.[/quote]

Back on shore, the harbor area was staged like a theme park, though it smelled like a moldy washing machine full of oyster shells. Japanese pilgrims held cameras close to the faces of the tame deer that staggered about stealing ice cream cones. From the shore, the torii was much larger, the tourists tugging at its broad cedar ankles, but it still looked marooned on the wet sand.

“When will the tide come in?” I asked.

“Oh gee,” Micah cracked, “I’m so sorry that I forgot my Seto Inland Sea tide table back in Tokyo. How would I possibly know that?”

I wanted to hike up Misen, but Micah said the native thing to do was take the mechanized series of small gondolas. We could then hike down on our own. We jogged up a stony path mottled with the shadows of maples, then settled into the five-minute ride. At the top, signs directed us toward the summit. They said the walk should take around 30 minutes.

“Now this is exactly the problem,” Micah said. “They’re great on quantification but terrible on qualification. The relevant data is not that this is a 30-minute hike ahead of us. It’s that it’s a very steep, very difficult 30-minute hike.”

The throngs stuck to the sites at the top of the gondolas, so the trail was ours. Occasionally, we would come over a rise and catch sight of the ridges of the back of the island as they fell off in broken planes toward the sea. At last we clambered up a narrow set of steps cut into the rock, past a makeshift summit shrine with a little red-bibbed stone idol, then hoisted each other over some smooth boulders. We caught our breath and sat in silence with the lowering sun in our faces.

“But I can’t see the torii,” I whined. “We’re looking the wrong direction.”

“Oh, come on,” he said. “Be patient for once in your life.”

The trail down the front of the mountain was a series of gentle switchbacks that ran between small wooden shrines. Alone with the darkening mountains of the main island across the strait before us, we took our time and didn’t feel the need to speak. We came to a shallow clearing before a precipice, and there, far below, was the gate.

The tide had come in, and the settled green of the sea lapped at the base. In the twilight the gate was floodlit from below, the cedar posts shining a glazed mandarin. The clean lines of the posts, the strength and durability of their frame, stood in sharp relief against their rippled, dim echo in the currents beneath. The cameras of tourists flashed from the perimeter like white fireflies in the expanding dusk.

“See?” Micah said. “Way better from up here.”

We caught a bullet train out of Hiroshima, transferred at the First Most Famous Castle Town to the northerly train toward the Sea of Japan, then transferred twice more. It was Sunday morning, and Micah seemed disappointed to find so few other people en route to the second of the famous Scenic Views, , or the “bridge to heaven,” a two-mile-long sandbar, upholstered with a thick hedge of black pines, that bisects a tranquil bay. Most of the time, Micah and I tried to get away from the crowds. But the point of this trip was the component of mass delectation. Though that wasn’t quite it. It was something closer to the feeling that we two were sharing something private in the midst of a crowd. Of the three views, Micah, for reasons he couldn’t quite explain, was most excited for Amanohashidate. Now he worried about the lack of visitors.

At the traditional inn near Amanohashidate, Micah asked our host in pidgin Japanese if this was the low season. No, said the diffident innkeeper, this was the high season—fall foliage had just peaked—but most visitors came on Saturday, not Sunday.

There wasn’t, then, a long line for the chair-lift that took us up the ridge along the eastern end of the sandbar. Speakers on the lift posts played jazzy renditions of too-early holiday standards: “White Christmas” and “Frosty the Snowman.” The hilltop was crowned with a ragged amusement park—three holes of mini golf and a set of bumper cars. The viewing station was a strip of twisted walkway that called to mind an M. C. Escher drawing.

The black pine forest of Amanohashidate, an unfaltering line of evergreen marching down the sandbar, was a natural feature, but the Japanese liked the trees so much that they planted many more; now there are some 8,000. On the far end, the ribbon of pine was notched into the base of a mountain lit with yellow gingkos and candied red Japanese maples holding their last leafy breaths. The visitors around us gasped in recognition; it’s an image they’ve seen hundreds of times, most famously in stylized woodblock prints. When the Japanese come for the view, they’re toting the history of its most famous interpretations, like American hikers gazing at Half Dome and remembering Ansel Adams.

The Japanese, however, didn’t seem to have all that much interest in walking across the sandbar; being on it presumably prevented taking it in. We passed crowds massed at the pier, waiting to take a speedboat across the bay. When we reached the gravel path that traversed the sandbar, we were almost alone. The brochures stated that the stroll would take precisely 50 minutes, but we figured we could beat that handily. The pines were spaciously allotted, their knotted trunks listing leeward to the sea. Some of the pines were set off with wide cordons as objects of appreciation.

“Micah,” I said, “it seems as though some of these trees are even named.”

“Of course they’re named,” he said. “How else could you rank them?”

“Wait, are they actually ranked?”

“I have no idea. But probably.”

In 40 minutes we reached the far side, where a second chairlift took us to a little bus that rolled up a mountain on a narrow lane through scruffy bamboo forest. At the top, the driver pointed in two directions and barked something in Japanese. One lookout was a ten-minute walk along the ridge. The second was a steep 40-minute hike up to the peak above us. Micah asked the driver for a recommendation.

“Oh! Oh! Oh!” the driver said. “View from peak, much better.”

All the other tourists opted for the easy ridge stroll. It’s not that the Japanese don’t like hiking: thousands of them climb 12,380-foot Mount Fuji every year. It’s that the Japanese trust authorities to make reasonable decisions. If the view from the very top were really worth seeing, somebody would have built another chairlift. This was only logical.

Micah jogged past cedar groves and bamboo copses, eager to reach the top before sunset. Each time we turned around, more of the network of bays and capes was revealed, and at the summit we found a sweeping vista. There was the broken cone of , one of Japan’s three Most Sacred Mountains, and further north the remote, windswept , where Micah had once talked our way into receiving free entry at one of Japan’s schmanciest hot springs.

Amanohashidate itself was just a thin band of green separating one blue sea from another; the quiet bays on either side were gently waked with the long V’s of tourist pleasure craft. Micah perched high up on a boulder and I sat on a bench, and for a few minutes we just took in the bay.

“Come here,” Micah said. “Let’s take another selfie.”

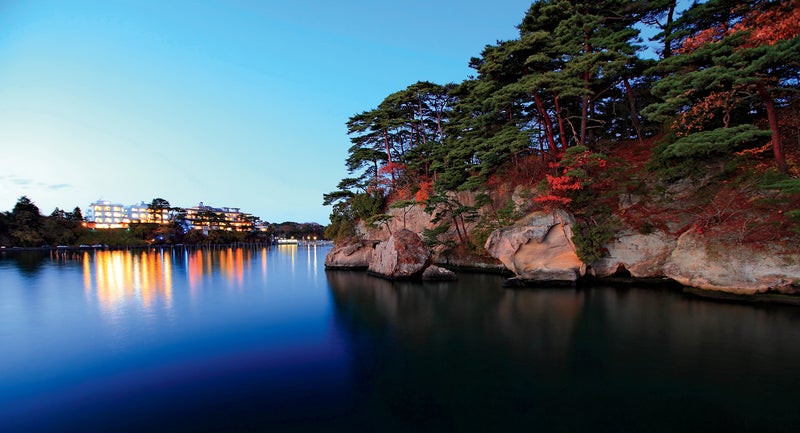

The third Scenic View, , is a constellation of nearly 300 islands in a broad Pacific bay, all of them sprouted with clusters of pines. We arrived at dusk after changing trains five times. Browning maple leaves disintegrated underfoot as we trudged uphill to a spooky hotel. We got drunk in the only open restaurant, where Micah showed the solitary chef pictures of our past few days.

“Oh,” the chef cried. “I live here beside one Scenic View but have never in my life seen the other two.” He thought for a moment. “One day, when I retire.”

In the morning, we were among no more than a dozen people aboard the first boat tour. Stiff, recorded English narration followed the Japanese version, but there was enough of a lag that by the time it began we had long passed whatever islands we were supposed to be learning about. It didn’t matter much; most of the islands were identical. Each featured bouquets of pines planted at oblique angles on plinths of coarse, top-heavy white stone. Darker rock at the submerged base lent an underline to the islands, making them seem as if they were floating just above the waves.

It was cold, and the tourists who weren’t huddled in the cabin threw shrimp crackers to seagulls. We had bought tickets for the lower deck, but once aboard we found that if we paid another 600 yen, or about six dollars, we could stand on the higher deck. Even here, in the bay rather than high above it, there was a premium placed on the better view.

“I look out at the beaches of the islands,” Micah said, “or the little hills and the little cliffs, and I think how fun it would be to be out there swimming and jumping.”

That wasn’t possible. Micah had to be back in Tokyo that afternoon to pack. For my part, in all my sojourns to Japan, I had never taken the narrow road to the deep north. I was going to continue on, toward Aomori and maybe even Sapporo, where it was already wintry. We had only an hour or two to hike up to a special vantage point in a park, a set of clearings cut into the hillside. The pine cover was too thick to see much, but here and there we spotted a sliver of green pine rooted on white stone awash in the gray water. We hurried downhill to catch our trains. At the station in Sendai, Micah pointed to the big board overhead.

“The Aomori train is that way,” he said, and began to turn. But I followed him to the Tokyo one. The adventures promised by Aomori and Sapporo could wait for another time. Or maybe I would never get there. Micah had those select minor places—bars, restaurants, parks—that he wanted to see once more over his last few days in Japan. I wanted to be there with him to take in, as it were, the private views.

is the author of .