IT WAS THE WORST STORY IDEA idea an editor could come up with, let alone assign to a real human being. That’s how I felt on Saturday, May 11, 1996, the day I heard Jon Krakauer had disappeared while reporting for ���ϳԹ��� on the growing phenomenon of commercially guided trips up Mount Everest a story I’d conceived and helped make happen by dealing with an endless stream of logistical headaches. None of that mattered when I heard Krakauer was missing in a deadly high-altitude blizzard. Had I sent him to his death?

Just 24 hours earlier, of course, I’d considered myself a genius. On the morning of May 10, Mark Bryant, ���ϳԹ���‘s editor, made an announcement at the daily editorial meeting in our Santa Fe office. “I have news from Jon Krakauer’s wife,” he quietly told some two dozen staffers. “Early in the afternoon, Nepal time, Jon made it to the summit of Everest.”

A cheer went up; there were high-fives. I pictured Everest, a three-sided granite pyramid jutting into the jet stream, ice crystals pluming off its top. Krakauer was up there in a snowsuit and oxygen mask, taking pictures and notes as he gazed out over the sprawling Tibetan Plateau and, in the opposite direction, the deep glacial basin known as the Western Cwm.

“How long will it take him to get down?” asked Leslie Weeden, a senior editor who tended to get right to the point.

“We’ll probably know something tomorrow,” Bryant said. Then he added, “Remember, he’s not down until he’s really down. A lot can happen on the descent. Keep Jon and all the Everest climbers in your thoughts.”

I cruised the hallways with a tremendous feeling of relief. At various times it had looked as if the project might fall apart. Trying to put a deal together with the guiding companies was a tenuous and maddening process. Krakauer, a longtime ���ϳԹ��� contributor with a reputation for being meticulous and brooding, was game from the start, but he needed occasional coaxing. Over a 12-month period, while he debated the risks, Bryant and I made the arrangements, eventually placing him with Rob Hall, owner of the New Zealand based guiding company ���ϳԹ��� Consultants. Needless to say, I was happy when Krakauer decided to go.

EARLY ON SATURDAY, my wife, Dianna, and I drove to the apartment of Alex Heard, a senior editor who was moving to New York and who, with his wife, Susan, was unloading stuff at a yard sale. We were pulling out to leave when Heard came running up, looking panicked. He’d gotten a phone call. Something catastrophic had happened on Everest.

“There was a big storm yesterday,” he said. “Climbers are missing. Scott Fischer is dead. They didn’t have any information about Krakauer.”

I felt disoriented, then my stomach flopped. “Krakauer is missing?”

I was too rattled to drive, so Di zoomed us through the adobe-lined streets to the ���ϳԹ��� building. Within 15 minutes, other staffers started drifting in. I burst into Bryant’s office, spouting the grim facts to his back. He turned away from his computer and looked up, stunned.

“Say that again?” he said.

People react differently to bad news. I almost started crying. Katie Arnold, an editorial assistant who did much of the fact-checking on “Into Thin Air,” would tell me later that she was seriously spooked after the news broke, she had nightmares in which climbers were immobilized in the clouds near the summit of Everest.

In the hallway, I heard muted giggles the news having inspired a bit of nervous black humor. John Galvin, an assistant editor, was talking to a few people about the Patch, a white rabbit pelt, purchased at our local Hobby Lobby, that Krakauer had carried to the summit as an odd souvenir for us deskbound editors. To make a long story short, the Patch had been used prior to Krakauer’s climb in a jokey nighttime ritual held near the Santa Fe ski basin, a quasi-pagan exercise designed to bring on a season of heavy snow. People couldn’t help wondering whether the Patch had worked too well. Krakauer didn’t know about the Patch’s origins when he took it up, but he admitted later that the coincidence slightly weirded him out.

Sick humor? Yes, but tension works itself out in strange ways. For my part, I spent the rest of the afternoon on the phone, trying to learn whether Krakauer was still alive.

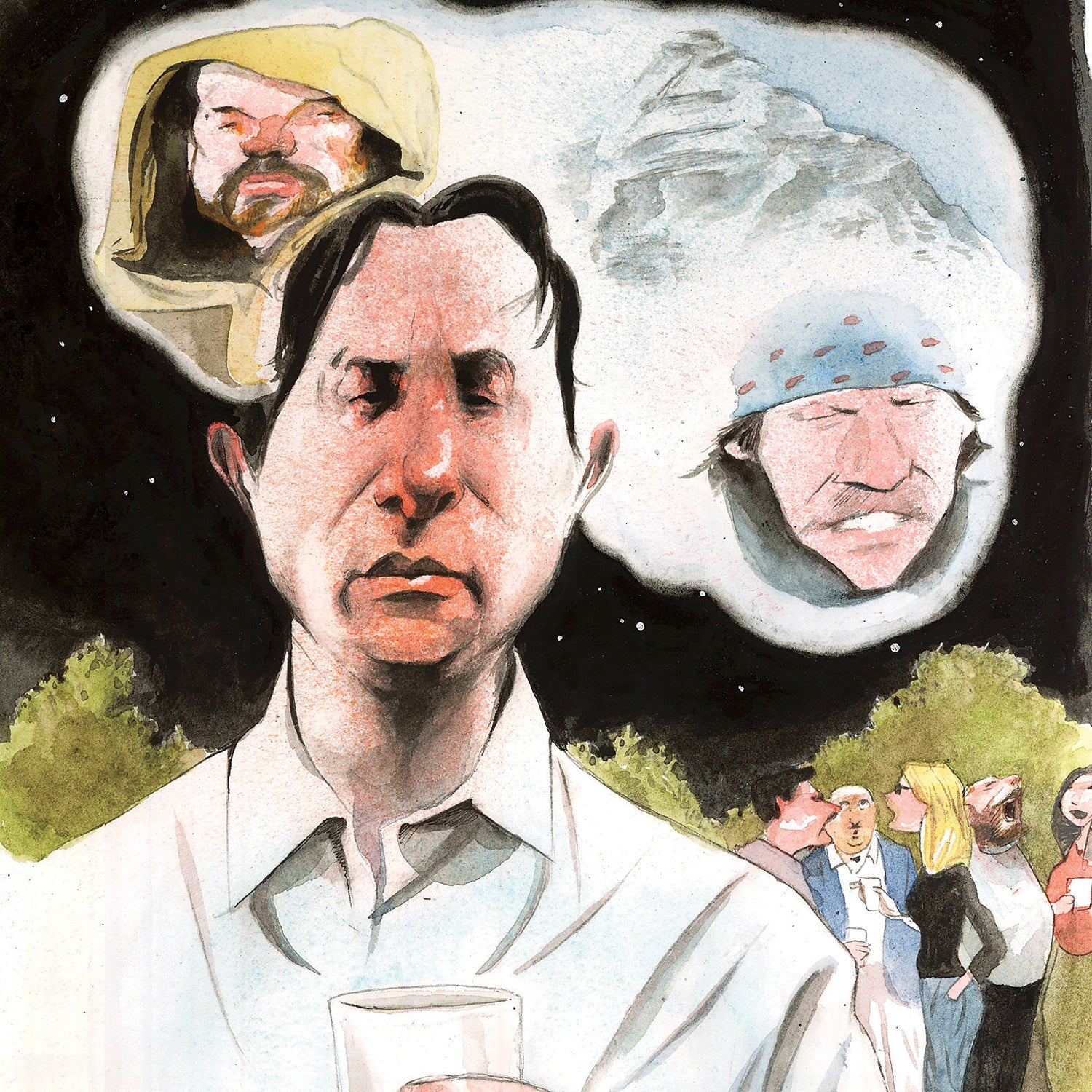

TODAY, WHEN I THINK of that Saturday, I think mostly of the night, which I remember as being black, eerie, and still. There was a going-away party for the Heards at the home of Hampton and Anne Sides Hampton was an ���ϳԹ��� senior editor at the time and by 8 p.m. their back patio was full of buzzing people downing chips and designer beer and talking about you-know-what. The usual going-away stuff had been arranged a fortune-teller, a guy in a chicken suit but Everest hung over everything.

Early in the evening, a local woman who’d done some high-altitude mountaineering showed up, and Heard bluntly told her that Scott Fischer the charismatic, ponytailed leader of Mountain Madness, the other commercial group that made its summit attempt the same day as Krakauer’s was dead. He wasn’t aware that this woman and Fischer knew each other through climbing circles. She instantly burst into tears.

That night I was a bearer of good if frustratingly incomplete news. Late in the afternoon, Bryant had stepped into my office and told me what Linda Moore, Krakauer’s wife, had related to him a moment earlier: Jon was now listed as accounted for. She had no additional details; later we found out that Krakauer made it to his tent just as the storm hit and spent the night shivering and delirious.

I arrived at the party with bad news as well. Rob Hall was stranded at 28,700 feet near the South Summit, trying to hang on in windchill temperatures estimated at minus 100 degrees Fahrenheit. Apparently Hall had stayed with a client who was having trouble getting down the Hillary Step. (It was Doug Hansen, we later learned.) People at Base Camp, talking to Hall via radio, pleaded with him to stand up and move his legs, but he couldn’t. As Hall’s wife, Jan Arnold, would tell Krakauer: “He sounded like Major Tom . . . like he was just floating away.”

THE FEELING WAS BEYOND BIZARRE. Hall was up there dying, and I was standing around with a beer in my hand. I thought about an issue that would be aired more than once in the months ahead: the culpability of ���ϳԹ���‘s editors. Of me.

Both Fischer’s and Hall’s companies had competed hard for the right to guide Krakauer to the top, but, clearly, they also seemed to have been competing on the mountain. It appeared that each man had ignored his turnaround time so he could get the most climbers to the summit. Were they motivated by a desire to show each other up in the magazine? Whatever had happened, I couldn’t help wondering whether our presence on the mountain had created the environment in which the disaster played out.

A few minutes later, I heard Hampton Sides’s voice from the kitchen: “Phone call for Mark.” I followed him inside. It was an editor at ���ϳԹ��� Online, our Internet partner, with updated information about Krakauer. He confirmed that Jon was alive. At the moment, he was descending the Lhotse Face with the storm’s other survivors, on their way to Camp II. From there, it would take them a few days to reach Base Camp.

Mark returned to the patio and shared the good news. And then he passed along the sad part of the story that everybody sensed was coming. “I’ve just been told that Rob Hall quit responding to radio calls a few hours ago,” he said. “Base Camp is presuming that he died.”

I went to the backyard, sat down on the lawn in the darkness, and listened to more of what Mark had to say. Unfortunately, the story he told was as black as the night.