I HAD MY PLANE tickets for Islamabad and the perfect travel companion waiting for me in Pakistan: Greg Mortenson.

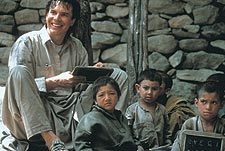

CAI founder Greg Mortenson with schoolkids in Korphe, Pakistan

CAI founder Greg Mortenson with schoolkids in Korphe, Pakistan

Greg is the founder of the Bozeman, Montana-based Central Asia Institute, a nonprofit humanitarian organization devoted to the well-being of the remote mountain people of the Karakoram, Kyrgyzstan, and Mongolia. He has spent much of the last eight years working in Baltistan, a region in far northern Pakistan bordered by Afghanistan, China, and Kashmir. Few Americans know more about this area, an intricate geopolitical knot as jagged and confusing as the landscape itself.

Greg and I had been planning our trip for six months. We intended to spend six weeks walking across the almost unknown mountains of far northern Afghanistan, living village to village. Greg had obtained promises of safe passage from various military commanders, including the leader of the anti-Taliban Northern Alliance, Ahmad Shah Massoud.

I knew a bit of the region’s history—tales of the Raj, the wars and diplomatic skirmishes of the Great Game, the lore of the Karakoram range. Greg undertook the task of bringing me up to date via a correspondence course in realpolitik. Among the books he sent: Eric S. Margolis’s War at the Top of the World, Ahmed Rashid’s Taliban: Militant Islam, Oil and Fundamentalism in Central Asia, Inyatullah Faizi’s Wakhan: A Window into Central Asia. I learned about the centuries of fractious Afghan warlords; about the British spies trickling through the country as far back as 1810; about the 47 British military expeditions, every one of which failed; about the Russian troops sent to conquer this graveyard of armies; about the inexhaustible intrigues of the CIA, the KGB, Pakistan’s ISI, Afghanistan’s KHAD; about the collusion and contradictions of the mujahideen, the jihads, the madrassas. Even on the most remote mountain trek, you are never simply traversing the landscape; you are passing through politics and history.

Then, on September 11, nineteen hijackers turned four U.S. passenger planes into missiles and massacred some 3,000 innocent people. I spoke to Greg, who was visiting CAI projects in northern Pakistan, via satellite phone, the connection fading.

“Massoud has been assassinated,” he said somberly. “Some of our military clearances have been compromised, and I’m no longer certain we have safe passage. Our exit in Faisalabad is particularly problematic.”

Greg and I discussed our options, both of us in shock and overwhelmed with a sense of loss.

“This is not only a horrific tragedy, it’s a taunt,” Greg said. “These terrorists want the U.S. to overreact. They want us to lash out indiscriminately. They want us to ignite a global jihad.”

We decided to suspend any decision about our journey for a few days, to see what time would bring.

I was gravely conflicted. Like all Americans, I was aflame with the desire to do something, to help, a frustrated passion whipped by the emotional winds of helplessness after so much evil and so many deaths. But the uncertainties and complications of war, it seemed, had trumped the simplicity of adventure. We had planned to go trekking through remote valleys along ancient trade routes, dreaming of history and of a better future for the inhabitants of those mountain outposts; now we would be passing through nervous, disconnected fiefdoms bristling with tension and bracing for the battles to come.

LIKE MOST OF MY generation, I never served in the military. I’ve seen the raw borderlands of hot and cold war, however, in South Africa and Burma, in Sierra Leone and Tibet. I’ve been arrested, interrogated, and detained by guerrillas and by “legitimate” military forces. I’ve sidestepped land mines, crawled under barbed wire, and ducked bullets with soldiers and mercenaries. I’ve met their victims. And now this tenuous trip to Afghanistan was forcing me to confront the contradictory relationship between war and adventure.

For much of human history, from the imperial triumphs of Alexander the Great to the conquests of colonialism and our own ultimately world-altering revolution, adventure and war were virtually synonymous. Boys, be they Vikings or Greeks or Mongols or Brits, were taught the fundamental skills of warfare. Swordsmanship, archery, and wrestling were the educational prerequisites for the great test of manhood. The same flags that flew vanguard over expeditions of discovery flew over the smoke and carnage of battlefields.br

Some of the world’s greatest explorers were military men: Sir Richard Burton, Major John Wesley Powell, Captain Robert Falcon Scott. Yet many were not: Ibn Battuta, Marco Polo, Fridtjof Nansen. Both kinds were driven as much by an inextinguishable curiosity as by a sense of national duty. In our own culture, Theodore Roosevelt might be considered the quintessential soldier-adventurer hybrid. He hunted, fished, climbed the Matterhorn, explored Africa; he also served as Assistant Secretary of the Navy and commanded troops and fought in Cuba. “War always does bring out the highest and lowest in human nature,” Roosevelt wrote in his 1913 autobiography, just before the outbreak of World War I. Veterans of the Great War, for one of the first times in history, spoke candidly about the conundrum that Roosevelt had acknowledged. Yes, in war there were untold thousands of heroic, self-sacrificing acts, but there was also untold horror and thousands of acts of cruelty and sadism. To those who had not seen it, war remained a grand and mysterious opportunity for adventure—but few who had seen its unspeakable depravity spoke of it that way.

TWO DAYS PASSED, and when Greg managed to get through via satphone again, the situation had further deteriorated. Radical clerics in Pakistan had called for a fatwa against their own government, and there was rioting in Peshawar.

“It might be difficult to travel right now,” he said. “Things are rather fluid.”

This was Greg’s laconic way of saying the region was a mess. We discussed our misgivings about adventuring through the fields of war: Our journey could potentially jeopardize the lives of those who had sworn to protect us, and yet the urge to go was still keen.

Greg, who is 43, came to his life’s work through mountaineering. He grew up in Tanzania and served in the U.S. military in Germany from 1975 to 1977. In 1993, already a veteran of several Himalayan expeditions, he went to climb K2. After a grueling 75 days on the mountain, during which time his team managed to summit two men, he stumbled down into a Balti village, emaciated, exhausted, spiritually drained. Nursed back to health by the villagers, he vowed to return, not to climb, but to help the Baltis build a school.

That promise took three years to fulfill. He wrote nearly 600 letters asking for donations, and 12 grant proposals, and got nothing. He had sold his climbing gear and his car, and was about to head back to Pakistan when the phone rang. It was Jean Hoerni, a Swiss physicist who had made a fortune in the microchip industry. Hoerni established the endowment that created Central Asia Institute in 1996.

CAI has since built 19 schools, 15 water projects, and four women’s vocational centers in Baltistan, and has launched several dozen community health programs that provide such services as cataract surgery and midwife training. It also supports refugee camps for women and children who have escaped the Taliban.

Doing CAI work, Greg has repeatedly put himself on the line. Five years ago, while visiting water projects in Wuzuristan, 200 miles south of Peshawar, he was kidnapped by a group of warring clansmen.

“Eight men with Kalashnikovs burst into my room at 2 a.m., blindfolded me, and drove me off into the hills,” Greg told me when we were first planning our trip. “I was held in a windowless mud room. At first I became deeply depressed. On the fourth day, I decided I needed to at least try to understand why I was a captive.”

He asked his guards for the Koran. They brought the Koran as well as a teacher. “I studied the Koran with this man, attempting to gain a deeper understanding of their point of view.” Greg ultimately learned that there was a dispute between two local tribes and that he was being held hostage as a potential bargaining chip.

“I told them I was expecting the birth of my first son,” said Greg. “This is a big deal in their culture. After eight days I was driven back across the desert and released.”

Greg believes that it was only through his willingness to reach across the gulf of understanding that he escaped unscathed. “It was a useful lesson for survival.”

WHERE DOES ADVENTURE lie in the range of human endeavor? Somewhere between sport and war.

Any great adventure is a physical challenge. A marathon may last three and a half hours; a Himalayan expedition is seldom shorter than three weeks. And yet it’s not simply stamina that is required, but technique developed through years of practice—the gymnastic ability to pull through a difficult move on rock, the uncoiling precision of a kayaker’s Eskimo roll. But adventure moves beyond the realm of pure sport at the point where sport moves into the realm of mortal consequence.

In most sports, if you make the wrong decision you probably won’t pay for it with your life. You may twist an ankle or break bones, but you won’t die. Make the wrong call climbing a big mountain or kayaking a big river, and it could be your last.

���ϳԹ���s have objective hazards. The jaws of an icefall, boat-swallowing holes, flesh-freezing cold. The secret of getting good at adventure is to develop the skills to accurately assess and circumvent these deadly traps. Some of us are still randomly picked off by rockfall, lightning, and storms, but most deaths can be attributed to bad judgment.

Not so in war. The risk of death, along with the crucial relevance of teamwork, esprit de corps, and trust, are where war and adventure overlap, but there are at least three fundamental distinctions.

First, obstacles in war are other humans (and their manufactured hazards—booby traps, bombs, bullets) who are incomparably more clever and unpredictable than water or rock or weather.

Second, in war, innocent people always die along with the soldiers. When adventure goes wrong, innocent people are not killed. ���ϳԹ���rs usually risk their own lives, not those of others.

Third, in war, participants are not allowed the freedom to make consequential decisions; they must face danger without holding authority over their fate. To maintain discipline amid the terror of war, the chain of command must be rigidly hierarchical. In adventure, the onus is almost always on the individual. This freedom of will is the embodiment of adventure.

Three days later Greg called again. He had just hitched a ride around K2 in a Pakistani military chopper, on the way back from visiting one of CAI’s schools.

“It was gorgeous!” he said, his voice sounding faint from the distance. “I don’t think there is a more beautiful place on the planet. I wish everyone could trek into this part of the Karakoram. But maybe right now’s not the time.”

I told Greg I’d been concerned about the prospect of reporting in a war zone after months of preparing to write about the adventure we’d organized, and that I was wrestling over the distinction between war and adventure.

“They’re poles apart,” he responded. “���ϳԹ��� is a building-up process. It’s about appreciating beauty, nature, and people. War is a tearing-down process.”

He launched into all he’d learned about himself and the world through adventure, from climbing Kilimanjaro in 1969 at the age of 11 to his life-changing attempt on K2 in 1993. Like the rest of us, he still has a list of hoped-for journeys: to follow in the footsteps of 19th-century British Great Game spies across the Himalayas; to ascend a number of unclimbed peaks north of the Hindu Kush; to walk across northeastern Afghanistan as we had planned.

“���ϳԹ��� is touching the fringes of your own physical, mental, and spiritual dreams. ���ϳԹ��� is connecting with other people. You know who are the best ambassadors for America? Not diplomats. ���ϳԹ���rs. Many villagers over here have seen the Rambo movies. But the the ones who actually meet Americans suddenly see us as humans, not villains. And these same travelers return home capable of seeing ‘the enemy’ as human. It sounds so trivial, so simple…”

The line started popping, his voice grew faint. “Mark, I’ll call you back. We have to make a decision.”

ON AN ADVENTURE you are self-selected, a volunteer; you participate of your own free will. In war, the challenge is to overcome the enemy, which directly or indirectly means killing others. On an adventure the challenge is not to take life, but to enrich it, to test one’s will and skill and stamina against the immutability of the earth. Yes, there is sometimes pettiness, selfishness, pride, and hubris, but the gestalt of adventure is still the antithesis of war.

Fascists and fetishists of war have smugly described adventure as an adolescent surrogate for war—as if war were the apogee of human engagement. But even with all the staggering acts of heroism that warfare can engender, even if giving your own life so that others may live is irrefutably the highest sacrifice a human can make, anyone who has been through a war knows the mendacity of such thinking. The boy I’d met on the border of Sierra Leone who’d had his hands chopped off by the rebels knows. The legless soldier in Russia knows. The nine-year-old girls in northern Burma who had been raped by government soldiers know. To all the victims, war—even when morally obligatory and politically unavoidable—is the zenith of human failure.

���ϳԹ��� opens doors to some of the highest human instincts—courage, camaraderie, patience, tenacity—without simultaneously opening a Pandora’s box of atrocities. I remember Andy Lapkass, retching with pleurisy, warming soup for me on the north face of Everest when I was too weak to even light the stove. I remember Belgian hang gliders rescuing me and my brother Daniel after he broke his leg deep in Morocco. I remember the maroon-robed Buddhist monks hiding me from the police in Arunachal Pradesh.

And yet adventure is largely a luxury of peace. And when peace fails, the spirit of adventure is inescapably twisted into the martial form of war.

GREG GOT THROUGH five days later. He was calling from Islamabad, where rumors of an imminent U.S. attack on Afghanistan were flashing through the streets.

“There are nearly 27 million Afghans and probably no more than 45,000 Taliban,” Greg said. “That’s one Taliban for every 600 Afghans. We helped create the Taliban. We funded them, we trained them, we used them in a proxy war to stop the Soviet Union from marching down to the Arabian Sea—basically to keep them away from our oil. Then, after we got what we wanted, we abandoned Afghanistan and its people to the Taliban radicals.”

Greg was appalled at the prospect of more killing in a country that was already “nothing more than a land of starvation, mutilation, and oppression.

“The Afghans know war better than any people,” he said. “They have had two decades of hatred, executions, torture. The long-term solution to terrorism is to help them. Feed them, clothe them, help them create a viable economic infrastructure. If we ever want to reduce terrorism, we will need the support of the Afghans.

“We have to show them that the world can be a better place. We have to show them love.”

I spoke to Greg one last time before he left for the refuge of the mountains. I told him I wouldn’t be coming over, at least not in the next few weeks. At this stage, any trip through Afghanistan could only focus on the crisis. The beauty, the history, the culture would only be footnotes to a story of death and destruction. Journalists from around the world were rushing to Pakistan and Afghanistan to cover the brutal play-by-play. I would not be one of them.

“It’s the right decision,” Greg said sadly.

I asked him what he was going to do.

“Stay here. Go back up to Baltistan. Work on the schools. You know, it sounds absurd, but perhaps none of this would have happened if women were allowed to go to school.”

In some fundamentalist Islamic cultures, women are forbidden even a basic education. The Taliban, who impose an unrecognizably distorted form of Islam on Afghanistan, deny women the right to learn to read and write. From the start, CAI has focused on education for girls and on the empowerment of women; each time CAI funds the building of a school, the villagers must agree to increase girls’ enrollment by 10 percent annually.

“Girls’ education has a major influence on a region’s quality of life,” Greg said. “Educating girls reduces infant mortality and overpopulation, which in turn reduces ignorance and poverty—the most fertile grounds for extremists.”

Greg Mortenson, like Sir Edmund Hillary before him, is a climber who came down from the summit with a conscience. In a ravaged part of the world, he is one man who has severed the Gordian knot entwining adventure with war, and instead has bound adventure to acts of kindness.

“No matter what happens,” he said, “the schools, the children, the mountains—everything that really matters—will all still be here next spring. You can come then.”