IN THE AFTERMATH OF EVEREST ’96, Sandy Hill was portrayed as a socialite who paid her way up the peak. In fact, Hill (she dropped her married name, Pittman, after divorcing in 1997) had been climbing since she was a teenager, and with her Everest ascent she became only the second American woman to have climbed the Seven Summits. A former television producer and writer, Hill married retired futures trader Thomas Dittmer in 2001 and now divides her time between New York, Miami, and Oak Savanna, her ranch and vineyard in California’s Santa Ynez Valley. Here, in an interview with ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° deputy editor Mary Turner, she talks about the heroes who saved her life, the infamous cappuccino maker, and why she thinks journalists mostly got it wrong.

Sandy Hill

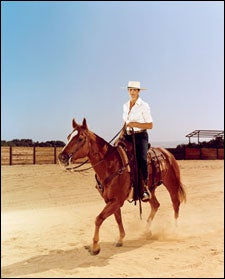

Hill at her California ranch in June 2006.

Hill at her California ranch in June 2006.I don’t think about Everest ’96 at all. It’s not that I deliberately don’t think about it, or can’t think about it┬ŚI just don’t. It was ten years ago. It seems to me that most people have figured out that most of what was reported in 1996 was prejudiced,

There was really only one writer who made scapegoats and pointed fingers and placed blame. That’s the writer who got the most airplay. I don’t really know him personally. I only met him briefly a couple of times. Most people think that because of the way so much of that year was portrayed, there was some intimate knowledge or something. That’s just not so.

How did it feel? Terrible. At the time, I was in mourning for the loss of our expedition leader, Scott Fischer, I was stunned by my own near-death experience, and my husband had filed for divorce a few months before I went to Everest. It was pretty much the worst year of my life.

Of all the coverage, Anatoli Boukreev’s book The Climb got the story best. Of course, it was written from the point of view inside his climbing boots, but at least I recognized what he wrote as being the same trip I was on. I didn’t write my own account because when I got home, I was paralyzed with grief. By the time the paralysis had passed, there had already been too much written by others, and at that point I would’ve been forced to write from a position of defense. That’s an ugly and inelegant place to start a book.

I wish I could’ve seen Everest then as I do today. I was privileged to have been on Everest three times, and in ’96 with such a wonderful team. We were together for two months, and for all but the last few days, they were some of the best times of my life. We had fun as a group, and that really is the memory that’s taken so long for me to feel comfortable feeling. Even though we were a commercial expedition, everyone was experienced, confident, and skilled, and we were a real team. If that weren’t so, none of us would have lived. Instead, because we behaved in the face of danger the way the book says a team is supposed to, all of us who were climbing together, watching and looking out for ourselves and the others, we all lived.

I credit two people with saving my life: Tim Madsen, for being there after everyone had made the dash back to camp and forcing me to stay positive and alert until Anatoli finally found us; and then of course Anatoli, who was in real life the kind of person that superheroes in the movies pretend to be. I remember his big hands reaching down to take mine and how he kept my wobbly legs stable until I got back to the safety of the tent.

I’ve always been sick about the way so many people second-guessed what Anatoli should and shouldn’t have been doing that day. I honestly believe that if he had deviated one single step from those that he took and had instead chosen to do anything different, as his detractors have suggested in hindsight┬Ślike use oxygen or not come down ahead of us┬ŚI for one would not be alive today. And I’ve always been sorry that Scott Fischer was not recognized for being the good leader and fine person that he was. He insisted that we go to the summit “like a Cub Scout troop marching in formation.” He said, “We go up together and we come down together.” We all did that, and I do think that’s what saved us.

I have no idea where the rumors started that I brought along a cappuccino machine. But my coffeepot is a single stovetop aluminum percolator thing that weighs less than two pounds. Once you have the coffee made, you put a little hot water and a spoonful of powdered milk into a lidded mug and shake it really hard to make it foamy. Then you pour coffee into the mug, and it’s like a fake cappuccino. I thought it was clever. The men do it and people say, “The dude really loves his java.” I do it and they say, “She’s so spoiled.”

I haven’t climbed since ’96. I hike all the time, and I went back to Everest Base Camp twice, the first year to build a memorial for Scott and the following year to make sure it was taken care of. My circumstances changed so much after Everest ’96: I wasn’t really in a position to keep climbing. I was a single parent. I still think climbing any mountain is a great and worthy goal, and no person should be so arrogant, cynical, or judgmental of other people to dismiss Everest or any other dream just because it’s already been climbed. I assume that everybody who’s there has his own reasons for being there, and I’m not in a position to judge who’s got adequate or inadequate experience. We’re all adults and capable of making our own decisions.

Sandy Hill is at work on a book called Entertaining at Oak Savanna, to be published by Artisan Press in 2007.