On a warm mid-April day in northeastern Nepal, on the outskirts of the village of Phaplu, scores of Nepalese—all of them blind or partially blind—lined up at a screening table in the grassy courtyard of the Solu Regional Hospital. They had walked or been carried here by the hundreds—Brahmans, Chetris, Rai, Tamang, Sherpas, Newar, members of the many tribes and castes commingled in the countryside—to undergo a form of treatment that they considered not so much modern as mystical. Around them, radiant sunshine strafed the crenellated, 20,000-plus-foot peaks of Khatang and Karyolung; schoolkids skipped along the hardpan main street past a convoy of porters hunched under their loads; teenage soldiers from the Royal Nepalese Army idled by the airstrip in blousy blue fatigues, rifles slung low like guitars.

Himalayan Cataract Project

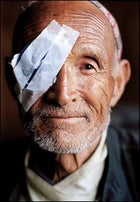

VISION QUEST: A post-op patient at an eye camp in Jiri, Nepal.

VISION QUEST: A post-op patient at an eye camp in Jiri, Nepal.Himalayan Cataract Project

“ITCHING TO GIVE BACK”: Dr. Geoff Tabin says goodbye to patients in Phaplu, Nepal. Behind him are his stepdaughter, Ali Demarchis-Tabin, and climber Pete Athans.

“ITCHING TO GIVE BACK”: Dr. Geoff Tabin says goodbye to patients in Phaplu, Nepal. Behind him are his stepdaughter, Ali Demarchis-Tabin, and climber Pete Athans.Himalayan Cataract Project

Dr. Sanduk Ruit and Dr. Geoff Tabin in Phaplu

Dr. Sanduk Ruit and Dr. Geoff Tabin in PhapluHimalayan Cataract Project

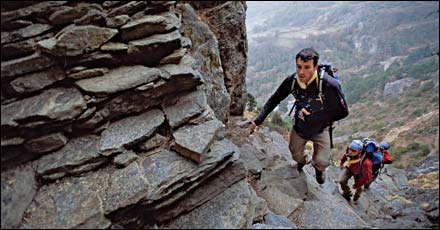

NOBODY’S BURDEN: Cataract patient Buddha Maya hitches a ride on her nephew’s back into Junbesi, on the trail to Phaplu, with climber Kevin Thaw bringing up the rear. After the surgery, Maya was able to walk home.

NOBODY’S BURDEN: Cataract patient Buddha Maya hitches a ride on her nephew’s back into Junbesi, on the trail to Phaplu, with climber Kevin Thaw bringing up the rear. After the surgery, Maya was able to walk home.Himalayan Cataract Project

BRIGHT EYES: A Tamang woman in Jiri, sight fully restored.

BRIGHT EYES: A Tamang woman in Jiri, sight fully restored.Himalayan Cataract Project

ON THE TRAIL TO CHOLATSE: Kris Erickson and Abby Watkins grind it out between Namche Bazaar and Phortse.

ON THE TRAIL TO CHOLATSE: Kris Erickson and Abby Watkins grind it out between Namche Bazaar and Phortse.But the patients were oblivious to all that. They waited, clutching their pre-op paperwork and the hands of their relatives, looking nervous or bewildered, lost inside themselves.

In the operating room—its spare furnishings limited to a stainless-steel table, a sink, and some antique metal cabinets—49-year-old American ophthalmologist and mountaineer Dr. Geoff Tabin sat in a ripped vinyl office chair, hovering over his first case of the day. For the past 11 years, Geoff has run the Himalayan Cataract Project (HCP), a U.S.-based nonprofit that’s raised more than $2.9 million to provide eye care in impoverished areas of Nepal, India, Bhutan, and Pakistan. The bulk of that money, $2.2 million, has gone to the Kathmandu-based Tilganga Eye Centre, whose surgeons have cured an astounding 74,903 cataract cases since 1994—including 34,070 at mobile eye camps like this clinic.

“This one’s like a 5.12,” Geoff said brightly, peering through his microscope into the milky cataract of a 76-year-old Nepali woman named Chandra Maya. “I’m going to take it real slow.”

Slow isn’t Geoff’s usual pace. The athletic, five-foot-eight physician—director of the Department of International Ophthalmology at the University of Utah’s John A. Moran Eye Center, in Salt Lake City—has so much energy that it pulses out of him in a nearly constant stream of ticks, twitches, and jokes. That energy has carried him up Mount Everest three times, among other peaks—hence his use of the climbing lingo. A less complicated surgery rates a 5.10. The simplest would get a 5.9, but that’s as low as he’ll go. Geoff is curing blindness, after all; it’s never exactly a walk-up.

Geoff swabbed the woman’s eye with a cotton ball soaked in Betadine, then propped her eyelid open with a speculum. The procedure required only local anesthesia, and the woman squirmed on the table. “No, no,” a nurse trainee barked in Nepali. “Don’t move.”

Geoff hooked a needle through the rectus, the gossamer-thin muscle that controls eye movement, then immobilized it with a suture. Next he angled in with a narrow scalpel called a crescent knife, making a small incision along the side of the cornea and working his way carefully toward the cataract—the eye’s opaque, calcified lens. The air was pungent and antiseptic, stoking my light-headedness as Geoff talked cheerily about his profession.

“Medicine is one of the great bastions of risk-averse overachievers,” he said. “You’re virtually assured money, a job, respect in the community. But how does that become meaningful? How does that make the world a better place?”

It was 7:30, almost dark, by the time Geoff started in on his 21st consecutive, and final, operation. He’d been at it for seven solid hours. No food. No water. No bathroom breaks. Johnny Cash piped in from an iPod plugged into portable speakers on a small desk, where Geoff’s 18-year-old stepdaughter, Ali Demarchis-Tabin, logged patient data into a laptop. (Geoff and his ophthalmologist wife, Jean, have a brood of five, including three kids from Jean’s first marriage.) Once again, Geoff reached the crux of the procedure: coaxing the lens through the small incision, a move about as easy as extracting the yolk from a hard-boiled egg without removing the shell. After a few tense minutes, the lens slid out cleanly; Geoff nonchalantly brushed away the wasted scrap of tissue.

The nurse handed him a small blue case, which contained a replacement interocular lens, or IOL, produced at a lab in Kathmandu. Using tweezers, Geoff carefully removed the tiny, pliable plastic disc. It was shaped like a miniature galaxy, with two curved spurs, called haptics, sticking out from opposite sides to secure it in place. He slipped it through the incision, which would seal without stitches, and leaned back from the table, his latexed hands floating in the air like a conductor’s.

“This morning she saw only light and dark,” Geoff said.

“Tomorrow she’ll have 20/20.

“Take a look,” he added, nodding down at the microscope. “It’s perfect.”

WE WERE IN PHAPLU as part of the Sight-to-Summit Expedition, a hybrid of altruism and adventure that brought a group of climbers, sponsored by The North Face (TNF), to volunteer for two weeks at two of the Tilganga Eye Centre’s mobile surgery camps, in the villages of Jiri and Phaplu—and then spend two more weeks climbing a 21,129-foot peak called Cholatse. If that seems like an unusual pairing of missions, it was. But it was also a new way to publicize one of the boldest public-health initiatives of the past quarter-century: the restoration of vision to tens of thousands of Himalayan villagers.

Cataracts are the world’s leading cause of blindness, typically forming after the age of 50 when protein cells in the eyes’ lenses start to harden, creating an expanding occlusion, like fog on a windshield. According to the Geneva, Switzerland–based World Health Organization (WHO), some 20 million people suffer from cataracts severe enough that they can see only light and dark; another 160 million are visually impaired. Even in the United States, more than 50 percent of people between the ages of 75 and 85 will experience some vision loss from cataracts, making cataract surgery the single most common major operation in America. In the developing world, cataracts develop unchecked and with greater frequency, due to factors that include higher-than-average genetic predisposition, disease, poor nutrition, and, particularly in mountainous areas like Nepal, intense ultraviolet radiation.

“There’s just so much need,” Geoff had told me when I met him in Kathmandu a week earlier. “The first time I came here, to climb Everest in 1983, I couldn’t believe the disparity between health care in the developed and developing worlds.”

Most families in rural Nepal scrape out a living farming small plots of near-vertical topography, getting around on foot over rough trails. Because even the oldest family members contribute to a household’s welfare, blindness takes a huge toll. The afflicted can be neglected and malnourished, and depression often sets in. One 1993 study of cataract sufferers in India and Africa by John Javitt, a Georgetown University ophthalmology professor, revealed that, once a person goes blind from the condition, his or her remaining life expectancy shrinks to barely a third that of otherwise healthy adults.

“I’ve seen patients treated like animals—worse than animals,” says Dr. Sanduk Ruit, the 52-year-old Nepalese ophthalmologist who cofounded Tilganga. “They’ll just get put in a corner and left there to die, some with no help whatsoever.”

Dr. Ruit grew up in a small trading village in northeastern Nepal, in the shadow of 28,169-foot Kanchenjunga. In 1968, when he was 17, he watched his older sister, Wangla, die of tuberculosis. There were no doctors in the area, and his family was too poor to get her to a hospital. It was a preventable and tragic loss, even then, and it propelled him into a life devoted to improving health care in his country. After graduating from King George’s Medical College, in Lucknow, India, in 1977, he went on to residencies at some of the finest medical programs n the world, including the University of Michigan School of Medicine and the All India Institute for Medical Sciences, where he specialized in eye care.

“What struck me about ophthalmology,” he says, “was how, in a short time, you could make such a difference in the lives of so many people.”

As recently as 1993, most cataract cases in Nepal were treated with an old-school procedure called intracapsular extraction, in which the surgeon simply cut out the lens and fitted the patient—now completely blind—with Coke-bottle lenses, essentially relocating the lens to the outside of the eye to restore limited sight. Of course, many patients lost or broke their new specs, leaving them worse off than before. Returning to Nepal in 1984, Ruit was apoplectic to see that his peers tolerated, even championed, such an inadequate solution. But they argued that establishing the IOL system would mean endless complications and exorbitant costs.

“They thought I was mad,” he says. “They thought I was just serving my own interests, that I was seeking my own fame and fortune. But that wasn’t it at all.”

Ruit teamed up with a brash and unorthodox Australian ophthalmologist and mountaineer named Fred Hollows, who’d come to Nepal in 1985 to research the bacterial eye disease trachoma for the WHO. Like Ruit, Dr. Hollows was outraged at the prevalence of outdated intracapsular surgeries—and famous for his explosive candor. Ruit recounted one legendary outburst, at a 1986 Kathmandu meeting of the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness, that had become a favorite story of Geoff’s as well. Ater denouncing the assembled medical VIPs as heartless imperialists clinging to a clearly second-rate method, Hollows finished with a hearty “Fuck you all!” and dragged Ruit off to the bar.

Ruit and Hollows dreamed up the idea of an eye hospital based in Kathmandu, one that could provide treatment for anyone who needed it. But there was a big hurdle: Interocular lenses from multinational suppliers cost at least $100 apiece—far too much for mass application among the poor. And another, graver problem soon presented itself: In January 1989, Hollows learned that he had kidney cancer. The prognosis wasn’t good.

Before Hollows’s death five years later, at age 63, he gave his friend a final gift: He established the nonprofit Fred Hollows Foundation, which helped fund construction of a lens-manufacturing facility that could provide IOLs for about $4 each. Factoring in labor, a procedure carrying a $3,000 price tag in the West could cost as little as $20 in Nepal. By 1994, Tilganga and the adjacent Fred Hollows Interocular Lens Laboratory were up and running—building lenses, treating eye problems, training physicians, and, four or five times a year, staging high-quality surgical camps in outlying areas. If the blind couldn’t come to Tilganga, Tilganga would come to them.

ELEVEN YEARS HAD PASSED by the time our crew of would-be eye-camp assistants stumbled out of a cramped bus and stood blinking in the bright afternoon light flooding the front yard of the Jiri View Hotel. The Sight-to-Summit roster included marquee alpinists like 43-year-old Conrad Anker—the Montana climber who made headlines in 1999 when he discovered the body of British mountaineer George Mallory, who’d died attempting Everest in 1924—and fellow American Pete Athans, 48, a seven-time Everest summiter, friend of Geoff’s, and self-described “jack Buddhist” with deep ties in Nepal. Also on board were Abby Watkins, 36, an Australian mountain guide living in British Columbia; Kevin Thaw, 37, a lively, lanky Brit and one of the world’s reigning big-wall specialists; Kristoffer Erickson, 31, a Montana photographer who, in 2002, became the second American to ski from the top of the 26,906-foot Himalayan peak Cho Oyu; and Jordan Campbell, 38, a public-relations consultant from Basalt, Colorado, who’d formerly run The North Face’s expedition program.

Along with Geoff and Ruit, the climbers would be featured in a documentary for Dish Network’s Rush HD channel, scheduled to air April 2, 2006, and being shot by Boulder, Colorado, filmmaker Michael Brown, a 39-year-old director best known for Farther Than the Eye Can See, an account of the 2001 Everest ascent made by blind American climber Erik Weihenmayer.

Brown had brought along Dave D’Angelo, 26, his Serac ���ϳԹ��� Films partner, and John Griber, 39, a big-mountain snowboarder and cinematographer who would do the filming up high on Cholatse. Telluride, Colorado–based photographer Ace Kvale, 46, and I rounded out the rest of the “Westies,” as Thaw liked to refer to the group in his Manchester accent. Finally, two Nepali climbers, friends of Pete, completed the roster: Ang Temba, 36, our base-camp manager, and Dawa Sherpa, 37, who was helping the film team. Grand total of Everest summits among the group: a hefty 17.

The Sight-to-Summit project represented a compelling evolution in the nature of big-time expeditions. Pete had helped Geoff at an eye camp in Mustang in 2003, and the two friends had dreamed of combining another camp with a climb—just the kind of thing that would appeal to TNF’s slightly revised sponsorship criteria. North Face–sponsored expeditions had long included cultural dimensions, but those aspects were formalized in 2004, when TNF partnered with Global Giving, a Bethesda, Maryland–based nonprofit that channels philanthropic donations through the Web. Proposals now hinged as much on cultural components as on adventure ambitions.

Though smaller neo-adventures had already taken place, this trip was the most ambitious attempt yet to fuse corporate philanthropy, high-altitude athleticism, and cause marketing, and there was something in it for everybody: The athletes would get to climb; The North Face and its parent company—Greensboro, North Carolina–based VF Corporation—would advance their philanthropic mission by ponying up close to $65,000 for the trip, including nearly $10,000 to pay for the eye camps; and Rush HD would roll out a high-quality film, one that might attract even more donors to the cause. Most important, several hundred Nepalis would have their sight restored. How it would all blend together on the ground, no one really knew. But it sure sounded good.

That first morning at the eye camp, the climbers busied themselves unloading supplies at the Jiri Technical School, a small vocational campus. The doctors had assembled a remarkably simple and portable system: two microscopes; several crates of sterilized drapes, face masks, caps, and rubber gloves; and a few boxes of sterilized instruments, syringes, anesthetics, blue plastic eye shields, and rolls of gauze and medical tape. Two small classrooms were swept out and lined with sheets of black plastic to create rustic operating theaters.

The camp had been advertised on the radio, and medical assistants had combed the hills, dropping leaflets and prescreening patients. Several hundred had gathered by the time Tilganga’s tan Toyota Land Cruiser arrived and disgorged the docs: Geoff bounding alongside the slightly older, slightly shorter Ruit, whose Buddha belly strained against his white polo shirt, his fleshy face scrunched into a broad smile as he greeted local officials. A few freaked-out patients had already bolted after seeing the anesthesiologist plunge a large needle directly into an eye socket, but now Ruit floated through the throng, touching and reassuring the people with warm tenderness. It was as if Siddhartha himself had strolled down from the high peaks.

Jiri was a homecoming for the two doctors. Geoff had come to Tilganga in 1994 as a corneal fellow from Australia’s Melbourne University, just in time for the center’s maiden eye camp. He’d grown up in the affluent suburbs north of Chicago, attended Yale as an undergrad, completed a master’s in philosophy at Oxford, and gone on to Harvard Medical School, a residency at Brown, and finally Melbourne. Over the years he’d found time to squeeze in some extracurriculars. In 1979, as part of Oxford’s Dangerous Sports Club, he’d been featured on he TV series That’s Incredible! as the first American to bungee-jump. In 1983 he was part of the first—and, to date, only—team to go up the American Direct route on Everest’s Kangshung Face, and in 1989 he became the fourth climber to complete the Seven Summits.

Although Geoff had arrived in Nepal full of self-confidence, the cases he’d confronted as a Western surgeon were nothing like the ones he saw in Jiri: advanced cataracts as large and hard as dimes. What’s more, he was accustomed to using a $65,000 microscope with a top-shelf Carl Zeiss lens, not the $4,000 model provided at the camp. In four days, the two surgeons completed 238 surgeries. Ruit performed 201, Geoff 37.

“I’d seen Dr. Ruit operate in Kathmandu,” Geoff told me with a laugh. “And he just made it look so easy.”

Ruit, for his part, was skeptical at first. Plenty of Western doctors had come to study with him, and few seemed particularly interested in helping the greater cause. But Geoff was different. “He had this strange restlessness,” Ruit told me. “He said the mountains in this part of the world had been a tremendous part of his life. You could tell he was just itching to give something back.”

The two decided to create HCP, which would funnel tax-deductible donations from the U.S. and keep Geoff returning to Nepal three or four times a year. By the time he and Pete Athans cooked up the Sight-to-Summit Expedition, Geoff was hoping to open up a whole new level of support—and get one last shot at making a formidable summit.

THE CLIMBERS WERE ITCHING to give back, too. But there seemed to be little need for high-performance workhorses from out of town. More than a thousand Nepalis had shown up for screening in Jiri, and so had hordes of local volunteers, including a dozen young nursing students from a local technical school who ran around in lavender uniforms, having a pretty good time elbowing the climbers out of the way.

The athletes did the best they could: Abby and Pete helped load syringes in the anesthesia room. Kevin escorted patients to and from surgery and post-op. Conrad was initially squeamish in the OR—a surprise, given all the dangers he’d faced on big mountains—but he helped Kevin ferry patients while the film crew angled for position.

At dinner the last night, the climbers were feeling a little underappreciated, and they sat around the table poking glumly at plates of rice and lentils. Pete said he expected things to improve in Phaplu, but everyone seemed to be thinking the same thing: Sure, the next camp might go better, but the trip there could get a whole lot worse.

We were about to begin a four-day trek east, through the Maoist stronghold of Kenja and over 11,581-foot Lamjura Pass, and it was almost certain we would encounter soldiers of the so-called People’s War, the nine-year-old conflagration between Maoist rebels and the Royal Nepalese Army. The already bad situation in Nepal had deteriorated since the summer of 2001, when eight members of the royal family were massacred by Crown Prince Dipendra. By 2005, close to 10,000 Nepalis had been killed on both sides, and in February the new king, Gyanendra, dismissed his parliamentary government and declared a state of emergency. Cell-phone service was shut off. Journalists were jailed. News was censored, and Nepali TV and radio were restricted to broadcasting little more than Hindu folk dancing and light sitar music.

While Westerners weren’t targets, tourism had gone off a cliff. Trekkers were routinely stopped by Maoist guerrillas and politely required to cough up a 1,000-rupee donation (roughly $23), but a few had been caught in the crossfire. A few days before we arrived, two Russian climbers on their way to Everest had been ambushed outside Kathmandu by Maoist soldiers, who lobbed three pipe bombs toward their taxi. One detonated on the floor of the backseat, tearing off the left heel of climber Sergey Kaymachnikov. His teammate, Alex Abrimov, was a seasoned Himalayan vet who’d been on Everest with Dave D’Angelo two years earlier.

“Seeing them really shook me up,” Dave told me after visiting the Russians in the hospital. “Sergey’s foot was hamburger. I don’t do well with stuff like that at all. I’m nervous as hell here—probably the most scared I’ve ever been in my life.”

Before the climbers departed on the trek, they had assumed everyone would be traveling together, but when we got up we learned that Geoff and Ruit had shipped out at 5:30 a.m. while we were still asleep. Since Ruit’s crew was traveling with a different trek organizer and porters, they operated on a different schedule. Also, as Geoff put it simply, “Dr. Ruit can be moody”—especially when he felt anxious about a huge crew of climbers traveling in Maoist territory. Considering that we were a dozen tall Caucasians decked out in matching North Face backpacks and toting more than $100,000 worth of camera equipment, it was unlikely we’d blend in with the locals.

Still, it felt good to be moving. The climbers, thoroughbred specimens all, had been cooped up for a week, and their mood improved with each step as we ascended the well-beaten dirt track out of the hazy valley. The town’s gritty bustle soon gave way to bucolic pastures and conifer forests. Periodically, the snow-glazed ramparts of Katang and Numbur broached the foothills, their faint, pearly dorsal fins etched against the tourmaline sky.

The next morning, we began the two-day, 6,000-foot climb up Lamjura Pass. We weaved through wagon trains of porters—men, women, and children—some flip-flopped, some barefoot, all tawny and coated in fine dust, humping hundred-pound loads of kerosene, rice, beer, ramen, and other staples along the steep, rocky trail.

One man carried a dhoko—one of the ubiquitous wicker baskets secured at the forehead with a tumpline—that had been modified into a crude chair and lined with fraying wool blankets. It contained an old woman with opaque white eyes, her head wrapped in a purple scarf, gazing blankly back down the trail. She was on her way to Phaplu.

In Sete, we drank hot Tang on the stone patio of our ramshackle teahouse while the sun sank toward the hills, as red as a rhododendron bloom. At dinner, the innkeeper brought us a note from Geoff, sent by a runner. He and Ruit were two hours up the trail in Goyem. Pete read the note aloud.

Jordan, Peter, Michael, et al.,

We have 2 patients with us. You really should come here. The one old lady has NO family and no money. Her village took up a collection to hire a porter to bring her. She went totally blind from cataracts a year ago… She would be perfect for the film, N face, etc. Plus she really does NEED the help. Please think about coming up at 5:00 AM and helping the rest of the way to Phaplu and during the camp! I will see you soon.—Geoff

Pete pocketed the note, shaking his head slightly. It was hard to argue with Geoff, but the urgency seemed excessive, especially since we’d been left behind. No one spoke for a few minutes, then Conrad piped up.

“If there isn’t 220 volts going into a situation,” he said, “Geoff will make sure there is.”

“Well,” Pete said with a sigh. “I guess we’re getting up early.”

We would indeed rise early to go and escort the old woman, Buddha Maya, whose porter turned out to be one of her nephews, to Phaplu. But it wasn’t until after the trek that I’d learn what else had gone on ahead of us. At the top of the pass, Geoff’s group, still ahead of ours, had been stopped by the Maoist regional commander. He was in his forties, with a dozen soldiers, some no older than 13, armed with antique flintlock rifles.

It was a cordial affair. Ruit was well known, even legendary, in Nepal. He had provided eye care both to the king and to Maoist leaders, and the commander appealed to him to bring the Maoist message back to Kathmandu. “We want to help the people here, not hurt them,” the commander said. But Ruit, who had once sympathized with the communist cause, had become stridently apolitical. The revolt had grown too violent, too damaging, too dangerous, he believed. He had no interest in being an emissary for either side.

Instead, he gave the commander a supply of first-aid materials and told him that some friends were coming up the trail, and that they should be allowed through. When we arrived in Lamjura, there was no sign of the Maoists, except for a crude hammer and sickle painted on a stone wall. We stopped at the same teahouse where Geoff and Ruit had sat with the soldiers a few hours earlier, drinking milk tea with Buddha Maya, then we pressed on, undisturbed and unaware, to Phaplu.

WE PULLED INTO the second camp feeling buoyant and eager to make our altruistic adventure a success. Pete was especially keen to see things work out. As with Geoff, his time for difficult summits was waning. He had recently gotten married to American filmmaker Liesl Clark, who had a son from a previous relationship, and the couple was expecting a baby in August. Pete had taken on a kind of emeritus status at TNF—Conrad called him “Celestial Pete Athans”—and it had empowered him to do some real good.

As much as any of us, Pete understood that in the world of nonprofit fundraising, as in high-altitude-résumé building, exposure was everything. If he could leverage his clout as a climber to help HCP and Tilganga, then climbing Cholatse was simply a bonus. “This is an experiment,” Pete told me. “It’s certainly the direction I want my own career to go, and it puts a human face on the brand.”

The spirit of philanthropy was all around us in Phaplu, a commercial hub of 6,500 people with a long history of hosting charitable foreigners. The Solu Hospital itself had been built in 1975 by Sir Edmund Hillary, followed by a school—groundbreaking goodwill projects that were tarnished for Hillary when his wife and daughter were killed in a plane crash on their way to meet him there that year. Now 86, Hillary doesn’t get to Nepal much anymore, but his work continues through the New Zealand– based Himalayan Trust.

Much remains to be done. Mingmar Gyelzen Sherpa, Solu Hospital’s sweet, melancholy director, told me that most people in the area still lack the simplest necessities: soap, birth control, antibiotics. The civil war wasn’t helping, he lamented; the Maoists had doled out uniforms, guns, and a call to action, but they weren’t doing much for the common good. Phaplu had been the site of several bloody melees, attempts to seize control of its airstrip, and Mingmar himself had patched together soldiers on both sides of the fight.

“Tourists used to come here and say, ‘It’s so beautiful. It’s so peaceful,’ ” Mingmar said. “And we would say, ‘What? It is just hills and rocks and trees.’ We didn’t even know what peace was. But now that we have lost it, we know.”

As the second eye camp ramped up, the climbers slotted into the work flow like old pros. Kris and Kevin took up posts in Anesthesia, wiping eyes with Betadine and wrapping feet in sterile blue bags. Conrad and Abby shuttled people to and from the OR. Jordan and Pete hovered near the operating tables, helping Geoff and Ruit, who seemed much more engaged with our team.

Each morning the doctors and patients would gather in the hospital’s sunny courtyard to remove the bandages from the previous day’s surgeries. This was invariably a joy-filled occasion. These old men and women were about to once again see their gardens, their goats, their stone homes built into green hills beneath gray mountains, the sweet, sooty faces of their grandchildren. They would have their lives back.

As the eye patches fell to the grass, one man leaped up and started dancing with Ruit. Another man, a wiry old Brahman proudly dressed in a threadbare army tunic circa 1970, stood up, clapped his heels together, and snapped his hand to his forehead in salute, his lower lip trembling, tears streaming down his craggy face.

“It is like seven suns,” a Rai woman in her seventies told me, clearly ecstatic. She was getting ready to leave with her granddaughter, who shared her symmetrical features and, now, identical brown eyes. She jostled the girl giddily. “Now I can see what my kids are feeding me.”

Buddha Maya’s bandages came off on the last day. She seemed mildly confused at first, then lit up, shuffling forward with gathering confidence and a brightening expression. She stood out in a blue North Face pullover given to her by Dawa. She touched the doctors and the climbers and then shuffled past us and out of the yard. A few people wondered aloud where she was going. Since she would be walking back home, she’d gone off to do what anyone would do after having their sight wondrously restored—she went shoe shopping.

DURING TWO WEEKS of eye camps, Geoff and Ruit had performed 255 successful cataract surgeries. Some 2,115 other Nepalis had been treated for everything from mild conjunctivitis to minor tumors. This time, the climbers had been able to fully participate in the process.

The work done, it was time to have some fun—that is, if clawing your way up an enormous, lethal, frozen mountain in the middle of the night is your idea of a good time. At 7:30 the next morning, the team piled into an Mi-17 helicopter for the short hop through low clouds to Syangboche, where we’d start the approach to Cholatse.

You cannot set foot in the Khumbu—home to Everest, Ama Dablam, Cho Oyu, and other celebrity peaks—without pausing to admire the global village in action. In the hub of Namche Bazaar, a few hundred feet downhill from the airstrip, the main street was clogged with eager vendors—”Come in, come in! Big sale!”—peddling yak bells and jewelry and knockoff climbing gear, North Face logos slightly askew.

Despite the fact that tourism countrywide was down as much as 50 percent, the Khumbu still percolated with activity. Everest was experiencing its busiest season yet, with more than 300 people on the mountain.

“Poor Everest,” Dawa sighed over pizza in Namche. “Why can’t people leave it alone?”

Dawa was a stout five feet tall and could haul a pack as big as he was uphill at a pace so brisk I had to trot, with virtually no weight, just to keep up. He’d grown up in the Khumbu and gone to work on Everest as a porter at age 20, working his way up to climbing Sherpa. He spoke five languages. Of all the locals I met, Dawa seemed the most keenly aware of the plight of his people. In June, he would set out to mountain-bike over 30 of Nepal’s 17,000-foot passes in honor of his eight-year-old son, Gelu, who has cerebral palsy, and to “inspire people toward peace, not war.”

“We’re chickens in a gold mine,” Dawa told me. “But all we see is the grain. We should be mining the gold. If we had a real government, you’d be working for me instead of the other way around.”

Empowering Sherpas was one of Conrad’s big objectives as well. In February 2004, he and his wife, Jennifer Lowe, and writer Jon Krakauer established the Khumbu Climbing School, training Sherpas on the crags around Phortse, seven miles down-valley from Cholatse. Working in dangerous conditions without technical expertise, too many Sherpas, Anker believed, were dying in mountaineering accidents. But by the spring of 2005, every Sherpa fixing ropes on Everest’s Lhotse Face had graduated from his school.

It was a three-day hike to base camp, 12 miles and more than 4,000 vertical feet up the Gokyo Valley. When we pulled into Cholatse base camp, at 15,500 feet, the team was a tad battered. I was feeling altitude’s familiar vise grip squeezing my skull. Abby and Jordan were coughing and wheezing with colds. Kevin was grappling with intestinal issues. And Geoff was moving slowly. This was his first Himalayan peak in more than a decade, and he would have to leave Cholatse early for Bhutan to meet with the king about a new eye program there.

“My biggest training day for this was a two-hour run,” he said as we turtled our way up the steep ravine that led into camp. “And I was sore for a week!”

Then there was the climb itself. To fix or not to fix ropes: That was the question. No alpinist worth his ice ax wants to be accused of climbing a mountain in lesser style than those who came before. Fixing ropes would give us a better shot at the summit, but it seemed tacky at best. Only 20 people had ever been to the top of Cholatse, and we didn’t want to treat it like a popular North American trade route.

Still, the mountain demanded precaution. “Does that look like Rainier or Denali?” Conrad said one morning on the trek as we viewed recon footage of the mountain. We shook our heads.

“Are we treating it like Rainier or Denali?” he asked. We nodded.

“I just think getting so many people up a technical climb like this is presenting more risks than it’s worth.”

At dinner that first night in base camp, we mulled our options in the mess tent, the large dome glowing yellow under a spray of stars, the shadowy massif of Cholatse due east. At best we’d have a two- or three-day summit window, so, ultimately, how we climbed Cholatse seemed less important than whether we’d have a chance to do so at all. We decided to use fixed ropes—but only on the lower half of the mountain.

Mountaineering is dismal business. The higher you climb, the worse it gets. You learn anew each time to hate cold, hate gravity, hate darkness and snow and ice and rock, hate gray, rehydrated food. You hate peeing in a bottle and crapping in an ice hole. You hate, hate, hate 2 a.m. You hate putting on frozen boots. You hate your runny nose. You hate headaches, stomachaches, lethargy, dizziness, sleeplessness, sunburn, windburn, cottonmouth, cuts, bruises, and belayer’s rigor mortis. You hate the ever-present, low-grade current of fear.

And yet you learn to love having climbed. Geoff was once asked at a slide show what qualities were essential to becoming a high-altitude mountaineer. “Great tolerance for pain,” he responded, “and a lousy memory.”

To climb on big mountains is to enter a realm of personal misery that’s both severe and pointless—until you consider that the severity itself may be the point. Suffering begets enlightenment, say the Buddhists, and enlightenment begets compassion. In many ways, high-altitude climbing is the antithesis of what it means to be a Westie, which is to say it eschews the comforts and luxuries and entertainments that distance us from one another as well as from our own mortality. I can think of no image more relevant to our rapaciously self-absorbed world than that of two climbers tethered together on a knife ridge, living by the mountaineer’s code: If he falls, I jump off the other side.

On May 12, after a 21-hour push, Conrad, Kris, Abby, Kevin, and John made it to the summit of Cholatse. I’d reached 17,500 feet a couple of days earlier before coming down with altitude sickness. Geoff nursed me through the night with diamox and ibuprofen, and then the next morning, as I descended, he went up. He climbed to 20,000 feet with Pete and Mike while Conrad and Kris punched out the route. After 24 hours, and a long ridge still to go, they turned around.

I HIKED PARTWAY OUT with Geoff when he decamped for Bhutan. “That’s probably the last hard Himalayan peak I’ll be on,” he said, looking back up at Cholatse’s southwest ridge. You could see the faint line of his tracks bisecting a snowfield high on the mountain.

“God,” he said, “we were so close, weren’t we?”

When it was time for me to turn back, we stopped and hugged awkwardly around our backpacks. He seemed genuinely sorry to go. The part of his life spent climbing difficult mountains was over, replaced by his medical career and his family—not a bad transition, but a transition nonetheless. For a moment, as though he were experiencing a brief power outage, Geoff stood motionless. A lammergeier, a massive Himalayan raptor, floated on a thermal. The day was crisp and clear, the ragged white skyline of peaks thrusting into the clear sky. A gust blew hard along the hillside, kicking up dust. Then Geoff starting talking buoyantly again.

“Hey, did you hear the one about the monk who found a mistake in the sacred Buddhist scrolls?”

I shook my head, and Geoff launched into a joke on the famed celibacy of those cloistered disciples.

“So the monk goes to the rinpoche, an old man who’s devoted all the days of his life to the monastic pursuit of wisdom, and he says, ‘Rinpoche, monks have been copying the texts by hand for nine centuries. We are worried that errors may have occurred.’

” ‘Impossible!’ says the rinpoche. ‘But I will check the original scrolls myself.’

“The next day the monk returns to find the old master with his head in his hands, sobbing. ‘Rinpoche, what is wrong?’

” ‘You were right,’ the master tells the acolyte. ‘I have found an error. It says, “Celebrate“! “Celebrate“!’ “

It took me a second, but then we both burst out laughing. Geoff turned and started hopping down the trail, tossing his hand up in a wave, moving fast to catch up with his two young porters. Then he rounded a bend and was gone.