Bloody War!

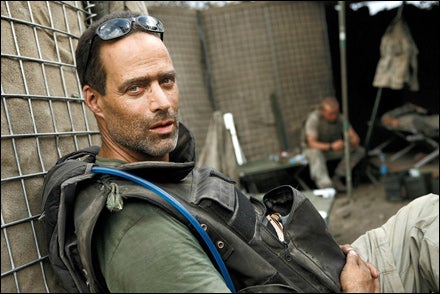

War, by Sebastian Junger

War, by Sebastian Junger

War, by Sebastian Junger“War is a lot of things and it’s useless to pretend that exciting isn’t one of them.” These words explain, in part, why Sebastian Junger, author of The Perfect Storm, spent the better part of a year in Afghanistan’s six-mile-long Korengal Valley, embedded with the U.S. Army, to write War (Twelve Books, $27, May). The title suggests the ambition of the work; Junger set out to write the definitive account of the modern soldier’s experience, and the men he embeds with deliver the goods. The Second Platoon of Battle Company is a collection of chain-smokers half Junger’s age who often fight the Taliban sporting nothing but shorts, flip-flops, and INFIDEL tattoos. Their home is Restrepo, a mountaintop base with no electricity but enough ammo to “keep every weapon rocking…until the barrels have melted…and every tree in the valley has been chopped down with lead.” Restrepo, named after a medic killed in battle, is also the title of a forthcoming film co-directed by Junger and photographer Tim Hetherington. The two-legged, Sebastian-does-Afghanistan project reminds us that Junger has become a brand. But his reporting reminds us that he’s earned his star: Junger grasps the soldier’s fear by living with it, once narrowly escaping death by IED. In April, the Army announced its departure from Korengal, and War will stand as a lasting account of the failed American experiment in this cruel little valley.”It certainly isn’t beautiful up there,” Junger writes of Restrepo, “but the fact that it might be the last place you’ll ever see does give it a kind of glow.”

Books: Playing God!

Lucy, by Laurence Gonzales

Lucy, by Laurence Gonzales

Lucy, by Laurence GonzalesIt’s hard enough being a teenager today. Just try it if you’re half ape. That’s the deal in Laurence Gonzales’s coming-of-age-except-I’m-also-part-bonobo biotech thriller, Lucy (Knopf, $25, July). Raised in the Congo by her scientist dad, Lucy is orphaned when insurgents attack their camp; she’s scooped up by a neighboring primatologist, an American named Jenny, and the two leave the jungle for weirder terrain: suburban Chicago. Boy, is Jenny surprised when Dad’s notebooks reveal what the reader already suspects: Lucy’s mom is a bonobo, artificially inseminated by the scientist. Lucy, it turns out, is beautiful, quotes Shakespeare, and prefers to nest in trees. But she’s got some ‘splaining to do when she tosses a wrestler across her high-school gym. Before long, things turn mighty dark for our girl as she juggles YouTube, her budding sexuality (bonobos are omnivorous lovers), and guys in white coats who chase the teen, hoping to open her skull in the name of research. Gonzales goes over the top with Lucy’s perspective on our fallen American lives—OMG, high school is just like the jungle!—but mainly this is an enjoyable ride that makes you think (just not too much) about what it means to be human.

Books: ���ϳԹ��� Heroes!

Wolf: The Lives of Jack London, by James L. Haley

Wolf: The Lives of Jack London, by James L. Haley

Wolf: The Lives of Jack London, by James L. HaleyIn Wolf: The Lives of Jack London (Basic Books, $30, June), biographer James L. Haley gives the Oakland-raised writer the chronicling he deserves. At 21, London had already toiled as a cannery stuffer, an oyster pirate, a game warden, a seal hunter, and a coal shoveler. Then a steamship docked in San Francisco with Klondike gold and London hopped the next boat north. His 1897 Yukon folly gave him material for The Call of the Wild and made him vow to give voice to the hardworking poor. There’s been speculation that misery caught up to him back in California (some called London’s 1916 morphine overdose a suicide), but Haley sees his death as an accident: London went out seeking sleep, not suicide. Haley stakes a claim here as a rising voice of the West, with a biography that’s perfectly suited to London’s two-fisted, fortune-seeking life.

Books: Endless Surf!

Sweetness and Blood, by Michael Scott Moore

Sweetness and Blood, by Michael Scott Moore

Sweetness and Blood, by Michael Scott MooreWhen Michael Scott Moore, a SoCal kid raised in Redondo Beach, moved to Germany as a political journalist, he discovered something shocking in das Deutsche wasser: surfers on Munich’s Isar River canals. That made Moore wonder: Is the globalization of surf culture a force for good or an ugly Americanization? He chronicles his quest for an answer in Sweetness and Blood: How Surfing Spread from Hawaii and California to the Rest of the World, with Some Unexpected Results (Rodale, $26, June). Moore drops in on surf culture in Japan, Morocco, Indonesia, Israel, Cuba, and the UK, charting both the history of the sport’s growth and its effect on local behavior. It’s a fascinating journey—Moore takes on everything from the politics of the 2002 Bali bombing to the lineup etiquette of England’s Severn Bore—that ends with a satisfying answer: Surfing may have been spread by America’s global expansion, but the sport’s positive chi has overcome its imperial origins. The eternal appeal of boards in waves boils down to what one Japanese surfer told Moore: “It has good energy.”

Books: Killer Animals!

Deadly Kingdom, by Gordon Grice

Deadly Kingdom, by Gordon Grice

Deadly Kingdom, by Gordon GriceDid you know that albatrosses once pecked at the eyes of shipwreck survivors? Or that caterpillars can bite? These facts and many, many more are on gleeful display in Gordon Grice’s Deadly Kingdom: The Book of Dangerous Animals (Dial Press, $27, May), a highlight reel of anthropophagy spiced up with dashes of science. Grice’s delight is palpable when he describes a shark eating a surfer “as if sampling pâté on a cracker,” his disappointment obvious when he concedes that “sharks and crocodilians are the only aquatic animals that unequivocally take people as prey.” The book is high on one-sided battles—Steve Irwin and Roy Horn get nods—and low on political correctness. There’s no they-have-more-to-fear-from-us-than-we-do-from-them malarkey here. Grice posits that, thanks to guilt wrought from the Jaws phenomenon, we fear predators less than ever. But that’s not why you should read this book. Read it for lines like this: “Men sped across the face of the water, propelled by unseen sharks.”

Books: Legendary Battles!

The Last Stand, by Nathaniel Philbrick

The Last Stand, by Nathaniel Philbrick

The Last Stand, by Nathaniel PhilbrickJust when you thought nothing more could be written on Lieutenant Colonel George Custer, along comes a brilliant narrative that gives new life to the U.S. Army’s most embarrassing domestic defeat. The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn (Viking, $30, May), by National Book Award winner Nathaniel Philbrick, rivals Evan S. Connell’s Son of the Morning Star: Custer and the Little Bighorn in its breadth and accessibility, following the converging paths of Custer and Sioux chief Sitting Bull. Philbrick blames the Seventh Cavalry’s massacre on commander General Alfred Terry, who knew Custer lacked the humility to back down from a fight and who has since “slunk back into the shadows of history, letting Custer take center stage in a cumulative tragedy for which Terry was…responsible.” The Seventh doesn’t come off much better, depicted as a band of drunk savages led into battle with those most famous of last words: “Boys, hold your horses. There are plenty of them down there for us all.”

Books: Crazed Jocks!

The Renegade Sportsman, by Zach Dundas

The Renegade Sportsman, by Zach Dundas

The Renegade Sportsman, by Zach DundasIt’s time we reclaim the raw heart of the game from what Zach Dundas calls the “sports-industrial complex” in The Renegade Sportsman: Drunken Runners, Bike Polo Superstars, Roller Derby Rebels, Killer Birds, and Other Uncommon Thrills on the Wild Frontier of Sports (Riverhead, $15, June). After reading this nationwide tour of alt athletics, you’ll want to join the Hash House Harriers, a Portland, Oregon–based running group that fuels up with beer. The Renegade Sportsman establishes Dundas, a first-time author, as a P.J. O’Rourke for the bike polo set: irreverent without the snark, and often hilarious. There’s someone drinking beer on nearly every page as he takes you deep into, in his words, “sports’ terra incognita, where the tigers and dragons and drunk cyclocrossers and lesbian rugby players dwell.” And Dundas doesn’t always feel the need to go the Plimptonesque immersion-journalism route. Instead of pedaling the Trans Iowa, a 300-mile gravel grinder through corn country, he opts for driving the course with Guitar Ted, a Nugent fanatic turned race director; the 22-hour drive proves to be a much greater—and funnier—sufferfest.

Books: Epic Quests!

The Last Empty Places, by Peter Stark

The Last Empty Places, by Peter Stark

The Last Empty Places, by Peter StarkA few years ago, ���ϳԹ��� correspondent Peter Stark dug up a satellite image of the United States taken at night, found the unlit areas, and began to plot. Like many Americans, he didn’t consider his country wild—too much connective pavement, too many yellow arches—but he wanted to prove himself wrong. So Stark traveled through Maine, Oregon, New Mexico, and Pennsylvania looking for emptiness. He failed: In every destination, Stark unearthed stories of the settlers and Native Americans who’d come earlier. That’s what makes the resulting book, The Last Empty Places: A Past and Present Journey Through the Blank Spots on the American Map (Ballantine Books, $26, June), so intriguing, both a solid refresher on our savage colonial history and a smart rumination on what it means to get lost. Stark’s conclusion: While there may be no such thing as a literally “blank” spot on the map, that fact can’t diminish the power of the wilderness. What he perfectly captures is the electric wonder a person feels when setting eyes, for the first time, on a fast river breaking through a forest. “In the blank spots,” he writes, “what exists, we hope, is meaning.”