We’ve barely begun our three-day trek through a wild region of Tibet, about a day’s drive southwest of Lhasa, and already the elevation has reduced me to a whimpering heap. Having eschewed the use of drugs like Diamox, I’m one of only two members on this 12-person tour (the youngest, and supposedly one of the fittest, of a group ranging in age from mid-twenties to mid-sixties) almost ready to turn back due to altitude sickness. We departed our tent camp at 15,000 feet just hours ago, and haven’t even come close to the high point, but we’re climbing through a snowy landscape, up a mountain pass that will top out at around 18,000 feet. “We” consists of a mostly high-spirited cadre of Westerners, porters, yaks, and me, riding a pony, because I don’t have the strength to walk. But technically I’m not even riding—I’m being dragged along lead-line style by our doting Tibetan guide, Tenzin. The pony, whose name is something like “Blah” or “Duh,” is shying at every rock and shadow while marching determinedly uphill—a combination of movements that only exacerbate my pounding headache and urgent desire to hurl. Meanwhile, my friend Bridget is scampering alongside us, snapping photos and laughing hysterically at our unintentional parody of Mary and Joseph trudging toward Bethlehem.

Tibet, trekking, Asia

The author, with a pack yak

The author, with a pack yakTibet, trekking, Asia

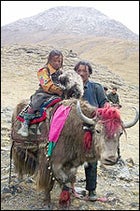

A herder-nomad and his daughter

A herder-nomad and his daughterTibet, trekking, Asia

A porter and his pack pony take a well-earned break

A porter and his pack pony take a well-earned breakTibet, trekking, Asia

A village boy smiles for the camera, while his shy friends turn away

A village boy smiles for the camera, while his shy friends turn awayThis is the “weekend warrior’s” trek. Unlike many Himalayan expeditions, which involve endless slogs into the frigid backcountry and require a fair amount of training and preparation, this trip is designed for the working man who craves adventure yet doesn’t have months of vacation time to spend finding it.

A new venture devised by Allan Wright’s Zephyr ���ϳԹ���s (a tip-top American travel company that somewhat incongruously specializes in rollerblading tours of Europe), the trip begins with a 13-day jaunt through the cities of Lhasa, Shigatse, and Gyantse, before embarking on the trek itself. The winding route through Tibet’s three major cities increases steadily in elevation for acclimatization purposes, and offers an edifying glimpse of both the Tibetan culture and the ravaging Chinese military-industrial presence in the developing areas of this beautiful but woefully oppressed land.

Right now, we’re shuffling through a snowy landscape of rugged peaks, marshy riverbeds, and the stony remains of settlements that have moved to warmer locales for the winter. Here, only a few groups of nomads eek out a living with their herds of sheep and yaks, subsisting on the meat and milk of those animals, and fueling cooking fires with their dehydrated dung. Our porters carry large thermoses of hot tea, and stop us every now and then to make sure we’re still drinking and staying as warm as possible in the sub-zero temperatures.

Soon, we approach a small village, and I’m instructed to dismount while the pony is fed some hay. I sit down on a spare feedbag, and a cluster of local women gathers around me. We stare at each other for a few moments. They’re dressed in heavy wool skirts with head-scarves and colorful aprons, signifying that they’re married. Most of them have weather-beaten but unlined skin, which makes it hard to tell how old they are. One of the women motions for me to come closer. I stand up and walk toward her, and she continues to beckon me closer until our noses almost touch. Then I realize what it is that she wants: a good look at my pale blue eyes. Our group has entered one of the many regions of Tibet where foreigners are virtually never seen, and the villagers I’ve encountered don’t quite know what to make of me. Just to see what will happen, I pull back the hood of my parka and remove my winter hat to reveal a mop of wavy blond hair. The women gasp and leap away. “In Tibetan religion, there are creatures with white hair and white skin,” Tenzin tells me. “They are something like angels. That’s what these ladies think you are.” (Translation: They think you’re a freak.)

After recovering from their initial shock, the women shyly offer me some rancid-smelling yak-butter tea, which I politely refuse, to no avail (there’s a Tibetan custom to refuse hospitality three times before accepting it), knowing I’m too sick to keep it down. Eventually, Tenzin intervenes on my behalf by telling the women something in Tibetan about the weak constitutions of white people, and motions for me to get back on the pony. As we crest the mountain pass, I begin to feel somewhat better and Tenzin encourages me to get off and walk—just in time, too, since the herders want to burden the pony with another woman on the tour who has become tired.

Later that evening, a brief white-out at dusk obscures the tracks of the hikers leading our group, and for a few heart-pounding minutes we stand in the blowing snow, turning this way and that, unable to find our way. Eventually, we regain our bearings and stumble, relieved, into our next camp. It’s a welcoming haven of oversized sleeping tents with cushy foam pads; a mess tent, a kitchen tent, and a bathroom tent—all miraculously set up by the porters before our arrival. This is luxury camping: We sit around a long plastic dining table lit by candles as the cooks serve roasted yak meat, rice, and cucumbers in vinegar. I barely manage to eat any of the delicious food, since the altitude has obliterated my normally voracious appetite.

The next day, I wake to a cup of black tea and a bowl of steaming wash water, and I notice happily that the tumult in my belly has subsided somewhat. After a leisurely breakfast of porridge, we commence walking, making our way up and over a six-mile pass and down into a breathtaking valley where the sun flits between clouds and the sky glistens an unreal shade of sapphire. As we crest the top of the difficult pass, I stop cursing and gasping for a moment to take in the scenery—but only after one of my fellow trekkers gently suggests, “The mountains are patient, take your time.” The group appreciates his sage advice, and we spend the better part of an hour lazing around in a huge meadow, telling stories and basking in the sunshine. Then we pick our way slowly toward camp—a few more downhill miles that bring us to a lower elevation zone where it’s warm enough to shed a layer of clothing. Eventually, we spot a quaint farming community peeking out of a rocky hillside. We sit down on the edge of a cliff overlooking the peaceful village, and watch as the residents thresh their crop of barley, singing all the while. In Tibet, Tenzin explains, there are prescribed songs for every occasion. When you are with your lover, you sing the love song. When you are praying, you sing the praying song. When you are working, you sing the working song, and so forth. But just then, a gang of children spots us sitting on the ridge and runs toward us singing a strangely familiar song: the “Ooh ee ooh ah ah” refrain from the “Witchdoctor Song”—a U.S. hit from the 1960s. I turn in astonishment to our fearless leader, Allan Wright. “That’s the song my girlfriend taught them when we came here last year,” he says, laughing. At that time, Allan, his girlfriend, and his guide, Jon Otto, were the only foreigners ever to have entered this village. A brief discussion with the villagers confirms that no other groups have visited them since. Last year, when questioned about their knowledge of America, the people of the community revealed to Allan and company that they had never heard of our country before. And, refreshingly, the names George Bush, Britney Spears, and Coca-Cola meant nothing to them.

We spend a pleasant hour or so spent visiting with the village children, who are eager to find out what treasures our daypacks hold. We entertain them with stickers and Polaroid photographs before continuing on the last half-mile or so to our next campsite. The sun is setting as we arrive at the tent camp, which is situated near the bank of a small river. In the distance, I see one of our porters coming toward the camp. He is leading the pony I rode when I was sick, but she barely resembles the frisky creature that marched so blithely up the mountain yesterday.

Her neck and flanks are lathered with sweat, and she’s favoring one of her hind legs. I ask Tenzin whether the porter would mind if I took the pony and helped her a little, to repay her for carrying me when I was so weak. He asks the porter, who shrugs and hands the reins over to me. I conjure up a bit of the horsemanship I learned in my youth, and feel down each of her back legs. The left one is hot and swollen around the fetlock, or ankle area, so I take her to stand in the river for a while, where cold water will reduce the swelling. I cover her with a wool blanket, to keep her from getting a chill, and when she’s cooled down I give her some grain mixed with hot water, a little sugar, and hefty dose of aspirin, “borrowed” from the expedition medical kit. That night, my appetite still eluding me, I skip dinner (and a rollicking conversation aided by a bottle of Tibetan barley wine, I later learn) and fall asleep easily in my tent—a relief after several nights of altitude-induced restlessness.

When I wake, I see that the pony is as good as new: perky, bright-eyed, and not limping at all. Our group packs up the camp, loads the yaks, and we set off on the last leg of the trek, a journey that we predict will take six to seven hours. But the hike is shorter than we’d expected. The route is a flat one that follows a shimmering river through red-rock canyons, and apparently it has changed course slightly since last year, uncovering a path that leads us easily past abandoned nomad villages with stone corrals and autumn-colored threshing fields.

We emerge from the canyon at our pre-determined pick-up spot in just under three hours, and with twinges of sadness that our excellent adventure is over, we thank our porters (and yaks, and pony), say goodbye, and pile into the three Land Rovers waiting to take us back to Lhasa.

Trip duration: 13 days total; including transportation days, visits to Lhasa, Shigatse, and Gyantse, and the trek itself (future treks will last four days instead of three).

Trek difficulty: Moderate. Twenty-four total miles of hiking over four days, with a few strenuous sections.

Price: $2,400; includes all meals, accommodations, and activities. Entry into Tibet is from Beijing, and Beijing to Lhasa airfare costs an additional $550 (flights are arranged by Zephyr ���ϳԹ���s).

Contact info: For 2004 itinerary and booking information, visit , or call 1-888-758-8687.