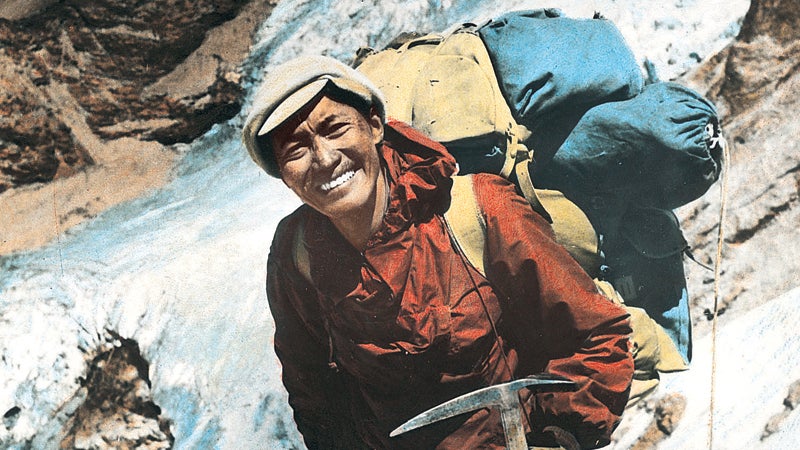

Babu Chiri Sherpa the greatest Mount Everest climber of this or any age, reclines on a couch, slurping milk tea, as his sidekick and business partnerÔÇöwhose first name is also Babu, but who goes by KarmaÔÇöfires up his Pentium PC, checks their e-mail, and downloads a large graphics file. Karma opens the attachment and a bright yellow-and-green design for a promotional ad appears on the screen. “What do you think?” Karma asks. “We’re making a new sticker.”

The obsolete version, one of which is pasted crookedly on the door to their third-floor office in Kathmandu’s Thamel district, is plain white and reads:

BABU CHIRI SHERPA, 9 TIMES EVEREST SUMMITER

NOMAD EXPEDITIONS

HIMALAYAN ADVENTURE TRAVEL SPECIALTIES

TREKKING, EXPEDITIONS, & TOURS

“Looks sharp,” I say of the new design, leaning toward the monitor to check out the text. The words are arranged around a photo of Babu, Nomad’s 34-year-old co-owner and star climbing guide, flashing an arched-brow grin with the peak of Lhotse in the background. “But it’s a little weird to say, “Two unique world records from Nepal.” A world record is unique by definition.”

Karma, a 38-year-old former monk, says something in Sherpa to Babu, who’s sitting under a curtained, glassless window; I can hear pigeons cooing loudly from the concrete ledge outside, along with car and motorcycle horns and the frantic ringing of bicycle rickshaw bells in the two-way street belowÔÇöa sharply crowned, heavily potholed lane barely fit for one-way traffic. Babu replies in a low, guttural grumble.

Karma turns back to me. “What should we say?”

“I don’t knowÔÇömaybe drop ‘unique’ because it’s redundant. You know what I mean?”

“Yeah, sure,” he says. “But we need your help because this is your language.”

“Well, I’d skip ‘Nepal.’ And it should say more about Everest, since that’s where he set the records, right?”

Karma nods knowingly and jots down a few notes.

“Yeah,” I continue. “I mean, who else would you rather have take you up Everest?”

Karma shoots me a wide-eyed look. “Here, will you write it?” he says, pushing his paper and pen at me.

We settle on the phrase “Who better to guide you to the top of the world?”ÔÇöa rhetorical question, really, considering Babu’s track record. He’s climbed Everest ten times, in good weather and bad, from the north and from the south, by himself and chaperoning clients. In May 1999 he spent 21 hours hunkered in a tiny tent at 29,035 feet, by far the longest any human being has stayed at the summit. Last May he sprinted from Base Camp to the top in 16 hours and 56 minutes, the fastest time ever. Except for the final 1,100 feet of his speed climb, Babu has accomplished all of this without the use of supplemental oxygen. And this season he plans to return and summit not once but twice, in the hope of breaking the record of 11 ascents, currently held by his compatriot Apa Sherpa.

“Other Sherpas don’t do this kind of stuff, and it says a lot about Babu’s ambitions,” says Elizabeth Hawley, the 77-year-old doyenne of the mountaineering community in Kathmandu, who has been keeping records of Himalayan climbs since 1963. “Babu has ambitions that go beyond the job.”

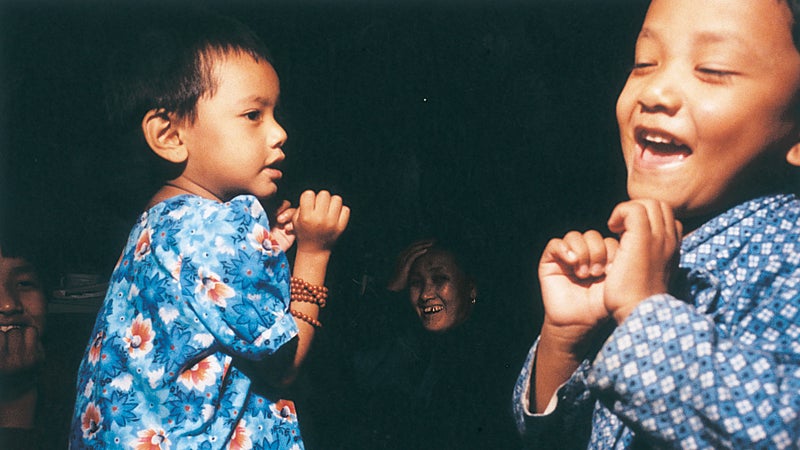

For starters, he has six daughters to put through elite private schools in Kathmandu. He’s trying to get a primary school up and running in a remote valley near Everest so local kids have a shot at clawing their way out of Nepal’s dismal status quo (45 percent of the kingdom’s 22 million citizens live below the poverty line; more than half are malnourished). And when he finally retires, he doesn’t want to end up like the vast majority of climbing Sherpas before him, scratching potatoes out of a patch of dirt and herding yaks, thank you very much.

Where those ambitions will ultimately take him is the subject of some spirited speculation. , a tent designer at Mountain Hardwear, Babu’s sponsor (Zemitis designed the shelter Babu used on top of Everest and calls Babu “Mr. Happy”), predicts that Babu will help to “put a new face on how people view Sherpas.” Jon Tinker, a British mountaineer who has climbed with Babu many times, declares that his friend is a “world-class quarterback” who is helping to push “the seismic shifts going on in Sherpa culture,” in part because he “scores goals, gets results, and has a Monty Pythonish sense of humor.” Tashi Jangbu Sherpa, president of the Nepal Mountaineering Association in Kathmandu, offers up what is perhaps the most unusual theory of all. “Other Sherpas, sometimes they get a tent, or a jacket, or an ice ax or something, but nobody has sponsorship like Babu,” he says “Babu has become an American.”

Like the other 110,400 Sherpas who live in Nepal, an officially Hindu kingdom, Babu is a Buddhist, and both his religion and his culture tend to place more value on humility than swagger. As a Sherpa who works in the Himalayas, he’s supposed to be a dutiful servant: a strong and gracious helper who schlepps the loads, cooks the meals, puts in the routes, and, when necessary, saves the lives of the foreign climbers who pay outfitters up to $65,000 to be guided up the tallest mountain in the world. And he’s supposed to do it all with a cherubic smile.

But Babu sees more in life than the praise, gratitude, and $7-a-day wages that have sufficed for more traditional Sherpas. He is charting a new course for Sherpa business opportunities, Sherpa cultural aspirations, Sherpa community responsibility. He is going global.

[quote]Babu’s ambitions go beyond his job: putting six children through elite schools, founding a primary school of his own, and making sure his retirement won’t be spent scratching potatoes out of dusty dirt. Oh, and becoming the most decorated climber in Everest history.[/quote]

“I want to change things,” Babu says. “A lot of Sherpas go to the mountain with fear, but that’s no way to climb. They have to go, because it’s a job and they’re being paid well for it. If they don’t have any education, they don’t have a choice. I want Sherpa kids to have options. If we can be more famous or more rich and we get that opportunity, we’ll take it.”

Still, despite all this, the enormity of his brand potential is just dawning on Babu and Karma. “Should we change the name,” asks Karma, “to Babu Chiri Sherpa Expeditions?”

But I’m no longer thinking about Babu’s marketing challenges. I’m pondering the days ahead. Babu and I are about to depart Kathmandu for a three-week trek to Everest Base CampÔÇöa Sherpa-style tour of Babu’s native territory and stomping groundsÔÇöand I’m becoming preoccupied by a rather unseemly notion: that this short, stumpy icon of Himalayan mountaineering doesn’t appear to be much of an athlete. Looking at Babu’s taut potbelly, which gives him the outline of a miniature Buddha, I begin to imagine myself handily outstriding him over high passes and along dusty yak trails.

Then the thought grabs hold: I can take this guy.

While trenching through waste-deep snow below Everest’s North Col on the afternoon of June 7, 1922, a teammate of George Mallory, who was leading the first attempt to climb Everest, triggered an avalanche that flushed nine Sherpas over an ice cliff and into a crevasse. Frantically clawing at the frozen debris, the British climbers and other Sherpas managed to free two of the men, one of whom was still alive after having been buried for 40 minutes. The other seven perished. Mallory later lamented, in a letter to his wife, “There is no obligation I have so much wanted to honor as that of taking care of those men.” (Expedition photographer John Noel, expressing a more imperial point of view, later wrote that the surviving Sherpas “had completely lost their nerve and were crying and shaking like babies.”) Those seven were the first climbers to die on Everest. Of the 167 climbers who’ve been killed on the mountain,┬á47 have been SherpasÔÇödouble the number of any other ethnic group or nationality.

Sherpas have lived in the Himalayas for nearly five centuries. They are an ethnic group whose nomadic ancestors migrated in the 16th century 1,250 miles from Kham, a province in eastern Tibet, via an 18,753-foot pass called Nangpa La, and moved into the Solu and Khumbu Valleys in northeastern Nepal. (“Sherpa” derives from the Tibetan word for “easterner.”) No one knows why they left KhamÔÇöTibetan genealogies are their only historical recordsÔÇöbut their tradition teaches that Guru Rimpoche, the eighth-century founder of Tibetan Buddhism, designated the Khumbu as a sanctuary to be used in a time of unrest; they were said to have been following magical descriptions in religious texts when they found the valley.

These high-altitude pioneers settled between 8,000 and 14,000 feet in the Solu-Khumbu region; people often refer to the two valleys as one, because together they’re the cultural heart of Sherpa country, and because they’re linked by the Dudh Koshi River, whose waters flow from Everest. They built houses of stone, tended yaks, and carved narrow terraced plots to grow meager crops of buckwheat and barley. “Sherpas have always lived on the edge,” says Frances Klatzel, a Canadian scholar who has lived in Nepal on and off for 20 years. “They were never able to grow enough food to last the year, and as the population grew, they traveled to trade.”

In the mid-19th century, hundreds of young Sherpa men left the Kingdom of Nepal to seek better work and higher wages as coolies on the tea plantations and road-building projects of the British Raj. Many flocked to the Indian hill station of Darjeeling. From there, after the turn of the century, British adventurers began staging their first surveys of the region around Everest. In the competition for work, Sherpas vied with virtually every hill tribe in the HimalayasÔÇöTibetans, Rai, Limbu, Bhutanese, and othersÔÇöand, as Babu is doing now, aggressively advertised and strived to demonstrate a superior tolerance for cold and high altitude. By the time Mallory’s 1922 expedition assembled for its monthlong trek north across the Tibetan plateau to Everest, the Sherpas had established a unionlike foothold that they’ve been building on ever since.

Over the next three decades, Sherpas distinguished themselves as high-altitude specialistsÔÇöhiring mules or Tibetans to carry loads to the mountainÔÇöwho would happily risk their lives for their sahibs. But they also fought for greater respect. John Hunt, leader of the 1953 British expedition to Everest that put Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary on the summit, learned this the hard way. As described in Sherry Ortner’s 1999 book, , upon assembling the expedition in Kathmandu, Hunt quartered his men inside the British Embassy and stuck the Sherpas in the garage. Furious, the Sherpas registered their outrage and solved a practical problemÔÇöthe garage had no bathroomsÔÇöby urinating in the road outside the embassy the next morning.

[quote]Sherpas distinguished themselves as high-altitude specialists who would happily risk their lives for their sahibs. But they also fought for greater respect.[/quote]

On that expedition, more than 350 porters were required to haul the team’s supplies and equipment. One of the laborers hired on was a 15-year-old boy named Lhakpa SherpaÔÇöBabu Chiri’s father.

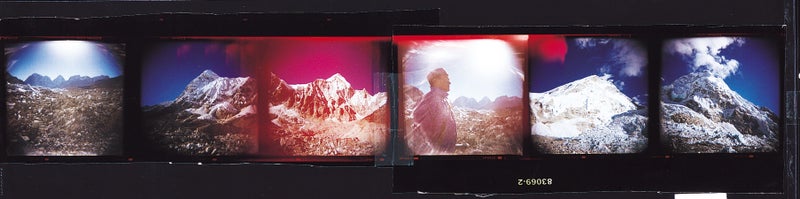

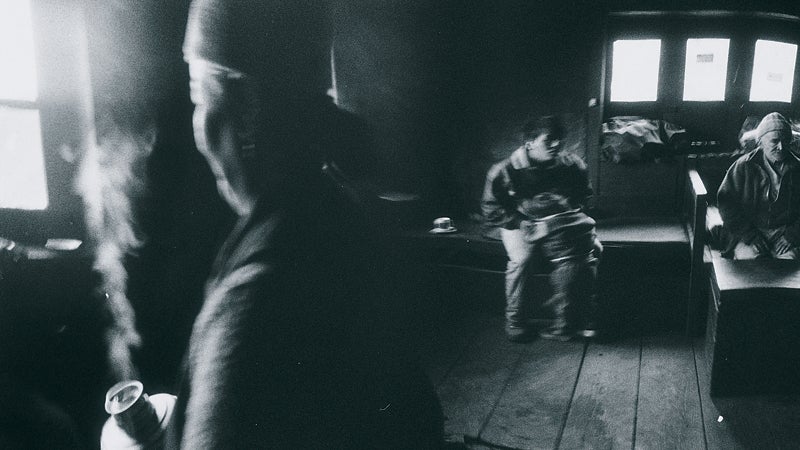

Together with the┬áphotographer Teru Kuwayama, we hop a twin-prop 20-seater from Kathmandu to the Solu village of Phaplu, plunking down on a canted gravel airstrip that could pass for a runaway truck ramp. Here we are joined by Nima Sherpa, a porter Babu has hired to help carry Teru’s camera gear for the trek. After a four-hour ramble on foot through deep gorges, past monasteries, and up steep, forested hillsides, we arrive in Chhulemu, Babu’s home village. We’re detouring from the main trekking route to visit Babu’s parentsÔÇöLhakpa is now 63, and Babu’s mother, Pasi, is 61. At the moment we are sitting in their one-room stone house. And they’re laughing at me.

I’m probing, with limited success, for details about Lhakpa’s lifeÔÇönamely, whether he’s ever worked as an expedition porter. Chongba Sherpa, 44, a friend from a nearby village, has been recruited as an interpreter. (In addition to Sherpa, Babu himself speaksÔÇöand to a limited extent, reads and writesÔÇöNepali, but his English is rudimentary.)

“Yes,” Lhakpa says. He has worked as a porter. And that’s all he offers.┬á

“How many times?”

“Once.”

“When was that?”

“Long time ago.”

“Can you be more specific?”

There is much rapid-fire discussion in Sherpa. Then, an answer:

“1953.”

“For the Hillary expedition!”

“Yes.”

“Wow. OK.” I’m at a loss for words. “How heavy was your load?” I finally ask.

“30 kilos.” Sixty-six pounds.

“He says you asking many hard questions,” interjects Babu. “Nobody ever asking these things in his life.”

But as Babu’s stout mother speed-shuffles around the room with her thermos, topping off teacups, I persist. It turns out that Lhakpa earned five rupees a day carrying a load from Traksindo to Tengboche for the Hunt expedition and has never bothered to mention this fact to his son Babu, the Everest mountaineer. Babu is unfazed by the revelation, obviously unaware that he could now use the word “dynasty” in his company’s marketing campaign. Neither father nor son can understand why anyone would care to learn such things about an anonymous, shriveled-up herder sporting a nice pair of Gore-Tex boots and a toothless smile.

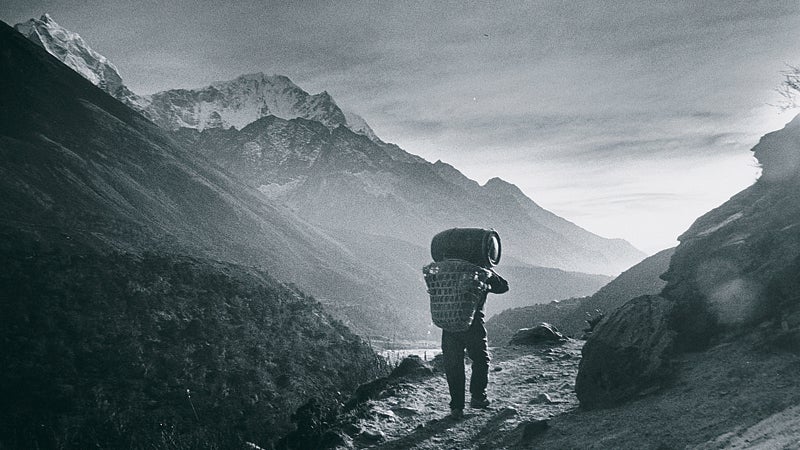

The 45-mile-long Solu-Khumbu Valley has no paved roads and no wheeled vehicles, not even wheelbarrows. (Babu’s parents have no electricity or running water.) Almost everythingÔÇöfood, cases of beer, timber, propane tanksÔÇöis transported by yak or on people’s backs. Though 80 percent of the Khumbu’s 3,500 Sherpas earn a living by catering to the 24,000 trekkers and climbers who tromp through the region every year, many below the Khumbu still get by as herders and farmers, just as they always have.

It’s the only existence Babu knew for the first 16 years of his life. Lhakpa and Pasi built their house 22 years ago, but Babu didn’t exactly grow up in it. The family grazed their cattle at higher elevations in summer, lower in winter, and thus spent much of the year sleeping with the livestock in temporary three-sided shelters woven of bamboo. Babu, the fourth of eight childrenÔÇöfour boys and four girlsÔÇöwas born in such a “cow house,” as he puts it, in 1966.

When Babu was 16, his parents arranged for him to marry Puti Sherpa, a woman from a nearby village who is three years older than Babu. The bridegroom was already scheming to run away to Kathmandu to earn money. (Two of his brothers had previously slipped off to the capital in search of work.) The trekking business in Nepal had started to boom in the early 1980s, and Babu found a job carrying a 66-pound load on a trek for about 17 cents a day. Having spent all his meager pay from that first assignment on food and bus tickets, he arrived home broke and in tears.

[quote]A lot of Sherpas go to the mountain with fear, but that’s no way to climb. They have to go, because it’s a job, and if they don’t have any education, they don’t have a choice. I want Sherpa kids to have options. If we can be more famous or more rich and we get that opportunity, we’ll take it.[/quote]

Two years later, Babu returned to Kathmandu and got a job as a trekking “cook boy.” Though only a slight promotion from porter, it meant a huge step up, because he no longer had to pay for his meals. Puti, who ran a tiny teahouse they’d started, soon gave birth to their first daughter, Yangdi.

Over the next seven years Babu spent each spring and fall as many Sherpa men do, hustling as much trekking work as he could, picking up snippets of English from clients, and hauling back cash and supplies for the teahouse and his extended family. And like many Sherpas, he had a higher goal: to land a position as a climbing Sherpa on an expedition to one of the 7,000- or 8,000-meter peaksÔÇöby far the best-paying and most coveted job in the Solu-Khumbu Valley. Getting hired on usually meant befriending or bribing (or both) the expedition’s sirdar, the Sherpa in charge of logistics and support.

In the spring of 1989 Babu got his first big break: He hitched onto a Soviet expedition that was planning to do the first traverse of 28,208-foot Kanchenjunga, the world’s third-tallest peak. The Soviets spent more than 100 days on the mountain, during which time Babu completed a crash course in alpinism and made an important discovery about his physiology. “When we reach Camp IV, a lot of Sherpas get sick,” he recalls. “I don’t have any kind of problem at altitude. I give help to other Sherpas and climbers; when I get to camp, I prepare some tea and soup.” After ten climbers completed the traverse, two of them, along with one SherpaÔÇöBabuÔÇöclimbed Kanchenjunga’s main summit. And unlike the Soviets, Babu got there without taking oxygen (or “English air,” as Sherpas on the Mallory expedition called it).

“It’s pretty much settled that Tibetans have an advantage at altitude,” says Lorna G. Moore, a professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center in Denver, who has studied high-altitude physiology for 30 years. (Genetically, Tibetans and Sherpas are virtually the same.) “But motivation, cultural factors, nutrition, training, gear, smarts, and a lot of other considerations apply.” Though Sherpas tend to have large lungs, blood vessels that don’t constrict in thin air, and a to pulmonary edema, individual Sherpas can succumb to the devastating effects of high altitude just like anybody else.

“It was like big exam, and they tell me I very strong,” Babu says of his prowess on Kanchenjunga. “I very happy.” He had punched his ticket as a climbing Sherpa, but the next challenge was to make his mark on Everest.

Bushwacking 2,300 feet down a steeply terraced hillside to the pearlescent Dudh Koshi River, hopscotching from one greening barley field to the next, we start our trek in earnest.

We make poor progress the first day because every 75 yards we’re hailed by another one of the neighbors, each of whom plies us with cups of hot tea and platters of boiled potatoes; you peel a spud, dip it in chili sauce, and eat it like an apple. The first dozen are tasty. At about the third stop, I take the risk of offending my host and refuse. Babu takes an entire platter.

Back on the trail, it’s finally time to challenge the master on his own turf. “How much do you weigh, anyhow?” I start in.

“Eighty-two kilos,” he replies. 180 pounds. He’s five-foot-five.

“Ever wonder whether you could’ve done the speed record faster if you weighed less?ÔÇŁ

“Not possible,” he says. “I try. My wife too good cook.”

Climbing up from the river, I make my move, striding urgently uphill with my 45-pound pack, opening up an early lead. Babu is carrying 25 pounds. Teru wears a knapsack and a belt slung with cameras. Nima has everything the rest of us don’t want to haul, maybe 70 pounds of crap, loaded into a full-size backpack with a duffel bag strapped on.

“What’s the matter, Babu?” I call down at one point. “All those potatoes weighing you down?”

He stops, lets out a throaty chortle, and starts trucking straight uphill, cutting the switchbacks. “I’m catching you!” he yells.

“Cheater!” I shout.

On the downhill stretches Babu runs full-tilt, taking the lead and skirting meandering yak trains, dollar-a-day porters carrying 120-pound loads, and the occasional horrified Euro-trekker (we aren’t exactly soaking up the scenery). Nima, clad in flimsy Chinese army-surplus canvas sneakersÔÇöAsia’s answer to Chuck TaylorsÔÇöstays right on Babu’s tail. I try to keep pace without blowing a knee. On the uphills, however, I regain my lead. Grinning devilishly as I pass him, Babu warns me that things will be different once we’re above 10,000 feet.

I’m still ahead by the time we get to the town of Lukla, where we spend the night. The next day we continue our yo-yoing on the five-hour walk to Namche Bazaar, a town of 1,647 people chiseled into a steep-walled cirque at 11,286 feet. We’ve arrived in the high country, the official opening to the Khumbu Valley.

Namche serves as the commercial center of the region, drawing people from several days away on foot to buy and sell goods every Saturday. Thanks to a nearby hydropower project, it boasts electricity, two Internet caf├ęs, three bakeries, and a number of rooftops sporting enormous satellite TV dishes.

[quote]Climbing up from the river, I make my move, striding urgently uphill with my 45-pound pack. Grinning devilishly as I pass him, Babu warns me that things will be different once we’re above 10,000 feet.[/quote]

Babu checks us into the Panorama Lodge, where many Everest mountaineers stay, in part because a flat stretch of land behind the lodge is a perfect staging ground for the yak trains that supply Base Camp. The owner is Sherap Jangbu Sherpa, 46, a member of the growing class of wealthy, educated Sherpa businessmen who have taken advantage of the ever-growing tourist boom. In addition to running his successful lodge, Sherap Jangbu leads luxury treks for outfits like Butterfield & Robinson; he also provides a dramatic measure of how far Sherpas have come in just a few generations. “My grandfather was a farmer, my father was a trader, I’m a guide and hotel owner, and my son is going to be a software developer,” he told me. Babu is trying to make the leap from Third World field hand to First World franchise in one generation.

He has been passing this way for over a decade, ever since he first got the opportunity to work on Everest in 1990. That year he signed on with an expedition led by Marc Batard, a Frenchman who a few years earlier had climbed from Base Camp to the summit in less than 24 hours. During Babu’s first season on the mountain, Batard planned to attempt his next stunt: spending eight hours atop Everest and then immediately climbing neighboring Lhotse from Camp IV. Batard reached the summit and lasted two hours before fear of frostbite forced him to descend, abandoning his sleeping bag and a stove on the summit. Babu, stationed at the South Col, asked Batard if he could take a crack at the summit and got a thumbs-up. He dashed up alone, gathered Batard’s stash, and hauled this proof that he had summited down to Base Camp. It was a formative experience in more ways than one: With Batard as a role model, Babu began to veer off the typical path for Sherpas.

The Panorama Lodge is also popular with trekkers, and here I meet the Seashols: Mike, Suzanne, and their sons, Matt, 28, and Pete, 24. The family takes one or two adventure-travel vacations a year. Mike is a software entrepreneur who has run 30 marathons, Suzanne is a preternaturally cheery and energetic trooper, Matt spent the last year traveling the world (42 countries, including Nepal), and Pete is a big-wall climber.

[quote]Though Sherpas tend to have large lungs, blood vessels that don’t constrict in thin air, and a built-in resistance to pulmonary edema, individual Sherpas can succumb to the devastating effects of high altitude just like anybody elseÔÇöeveryone but Babu.[/quote]

The Seashols love Sherpas. “I’ve never seen people with such an incredible strength-to-weight ratio,” Mike tells me. “They’re so strong! And humble. And gracious.” Suzanne chimes in: “The best part about being with these people is that they are so gracious about sharing their culture. They’re wonderful people. Every question I ask, they answer.”

The Seashols register only one complaint. “It’s been so hard to find people wearing traditional dress,” says Matt over breakfast one morning. Just then I notice Babu entering the dining room wearing a red Mountain Hardwear WindStopper Flex jacket, a pair of khaki Mountain Hardwear Supplex Pack Pants, and a purple Mountain Hardwear WindStopper Nut Beret.

Twenty minutes┬áout of Namche we get our first view of Everest. The dark, humpy peak sneaks in and out of view over the next couple of days as we climb higher into the valley. Pines and rhododendrons give way to scrub brush, until eventually, at around 14,000 feet, there is nothing but moraine. Tablets and boulders carved with Buddhist prayers in Tibetan serve as cairns to lead the way through the drab foothills. Several hours beyond Periche, the last permanent settlement on the trek to Base Camp, we reach 16,000 feet. I’d like to be able to report that I’m holding my own against the great Snow BearÔÇöas Babu’s Sherpa admirers call himÔÇöbut he only seems to grow more robust as I start to bog down in the thinning air.

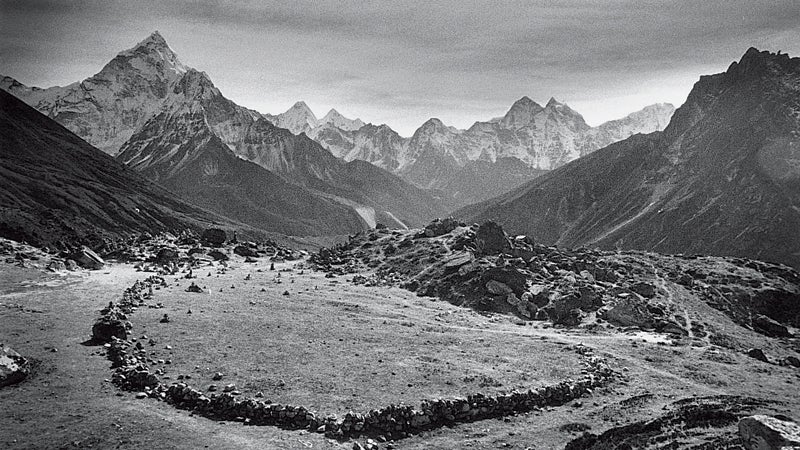

He is waiting for me over a rise. Up ahead, silhouetted against the backdrop of a barren, dun-colored ridge, hundreds of neatly stacked rock towers are scattered helter-skelter across a low knoll. They’re monuments to dead climbersÔÇönot gravestones per se but carefully constructed shrines. Babu and I wander into the sanctuary, looking at chest-high tablets inscribed with epitaphs for both Sherpa and foreign climbers. One stone is dated 1957. Babu pauses in front of a particularly imposing shrine set off by itself. “He was a very good climber,” he says. “It was a waste. He shouldn’t have died.” The stone is dedicated to Scott Fischer, one of the two guides who died in the 1996 disaster on Everest.

Another few hours ahead, set off the trail, is a cremation site for Sherpa climbers called Chukpo Lare (“Rich Man’s Yak Corral”). When the body of a dead climbing Sherpa is recovered, it is brought here, burned to ashes, and ceremonially placed inside a small shrine of stacked rocks. Because Buddhists believe that humans lose their individuality after death, there are no names on these shrines. For Sherpas, there is no more powerful reminder of their mortality in the face of the surrounding peaks than this place. “The whole category of gods who inhabit mountains tend to be irritable,” says Sherry Ortner, the scholar of Sherpa history. “They’re powerful beings who will protect you if you treat them right and who will really give you some bad trouble if you don’t.”

Indeed, climbing Sherpas and their families live with fear just as all climbers and their families do, which is why some end up making the choice of 34-year-old Ang Temba Sherpa, an accomplished climber and businessman at whose lodge we stayed in Pangboche. He first summited Everest in 1991 with the Sherpa Expedition, an endeavor designed to showcase Sherpas’ technical climbing skills and to demonstrate that they’re more than barrel-chested workhorses. After Ang Temba descended, his wife, Yangjing, congratulated him on his accomplishmentÔÇöand then informed her husband that one Everest summit was enough. But six years later he accepted an invitation to join another Everest expedition, knowing that his wife would never agree to let him go. “So I made a lie to her,” he told me. He convinced Yangjing that he was going to visit some friends in Canada and then hooked up with the expedition in Kathmandu. Yangjing got word of his subterfuge, and gave him a tongue-lashing when he returned from the unsuccessful attempt from the north side. “I don’t need moneyÔÇöI need you,” she told Ang Temba. When Babu spent 21 hours atop Everest, his wife back in Kathmandu became so worried that she stopped eating and fell ill. It makes little difference to these women that the Nepalese and Chinese governments require each Everest expedition to insure every climbing Sherpa’s life for $3,500.

Unlike Americans or Europeans, Himalayan Sherpas consider high-altitude climbing to be decidedly unglamorous, dangerous, dirty work. In 1983 Tenzing Norgay’s second son, Jamling, asked his father’s permission to join an Indian expedition to Everest. Tenzing refused, saying he wanted his son to finish high school and go to college. In Jamling’s memoir, , which will be published in April, he recalls his father’s words: “I climbed Everest so that you wouldn’t have to…. You can’t see the entire world from the top of Everest, Jamling. The view from there only reminds you how big the world is and how much more there is to see and learn.” Tenzing died in 1986, and Jamling eventually summited in 1996.

Climbing Everest is formidable enough, but in January 1999, Babu set in motion an even more daunting plan.

“It was hilarious,” says Martin Zemitis, the Mountain Hardwear tent designer. “This five-foot-something guy comes in, hardly speaking any English, and says it’s his dream to spend the night on Everest. I go, OK, we get nuts all the timeÔÇöwe were based in Berkeley thenÔÇöbut this was off the scale. Above 26,000 feet, technically, you’re dying, right? Here’s this guy wanting to stay up there, and nobody really knew if it was possible.”

Once Zemitis learned that Babu had been up Everest eight times without supplemental oxygen, he started taking him seriously. Four days later, Zemitis says, he handed Babu a 2.5-pound shelter the size of a doghouse that was “stronger than snot.”

He also informed the marketing department that Mountain Hardwear was sponsoring Babu Chiri Sherpa. “I was a little miffed at first,” says Jennifer Slaboda, the company’s marketing director. “I thought, Wait, this is going to be a liability issueÔÇöwhat if he dies up there? But now that I know Babu, he’s great to work with.”

Nearly two years later, Babu, Teru, and I arrive at Everest Base Camp, elevation 17,500 feet. Standing amid the December silenceÔÇönobody’s here but usÔÇöit’s almost impossible to picture the transformation that occurs every April. Last season there were more than 500 people here, milling about among huge dome tents, webs of billowing prayer flags, and stone shelters that crumbled after the season with the heaving of the glacier.

This is Babu’s home away from home. He points to where the Khumbu Icefall peters out into the moraine, the very best site at Base Camp because it offers the cleanest water and up-to-date information on route conditions from descending climbers. Babu snagged the spot last year by dispatching a friend to stake it out two months before the season even started. “The last camp before the icefall is a critical spot if you want people to know what you’re doing,” says Jim Litch, an American climber and physician who has provided medical care on a few of Babu’s expeditions. “Babu sets the stage, which is what any good performer does.”

It is difficult to get Babu to offer reasons beyond the mundane to explain why he decided to do the phenomenal things he did in 1999 and 2000. For example: “Just climbing the mountain isn’t good enough. I want to give something back.” He also cites the need to educate his six daughters. He acknowledges the influence of Batard. But the most succinct reason he offers for his feats is this: “It gives me power.”

In 1999 Babu planned to summit with two Swedish clients. The winds at the South Col were so ferocious, however, that his clients couldn’t get beyond the Balcony at 28,700 feet. On May 5, Babu pushed on to the top with his older brother, Dawa, and another Sherpa, Nima Dorje, who helped him dig out a platform for the tent and anchor it to the mountain. Babu crawled inside his 20-below down sleeping bag wearing a 20-below down suit, and commenced waiting.

Doctors had warned him that if he fell asleep he would never wake up. He was supposed to report in via radio every two hours or so, but “nobody could reach him on the radio that night for seven or eight hours,” says Heidi Howkins, an American climber who was at Camp II at the time. “His teammates were panicked about it, crying. They were doing frantic updates on their Web site, absolutely convinced that something had happened to him. It turned out that Babu had been talking all night long with some guys on the Tibet side, making crank calls on his radio. He was calling other base camps and waking them up.” After his 21-hour slumber party, he was greeted by a tsunami of publicity and a parade in Kathmandu.

For an encore, Babu decided he’d climb Everest faster than anyone else. The record was held by Kaji Sherpa, who made the trip in 20 hours in 1998. (Starting from Base Camp, an acclimatized mountaineer usually takes four days to summit.)

On May 20, 2000, Babu left Base Camp at 5 p.m. wearing light hiking boots. He took 40 minutes to eat and change clothes at Camp II and 35 minutes to do the same at Camp IV, which he reached at 2:35 a.m. The wind was blowing at more than 58 miles per hour at the South Summit. Babu proceeded to dash upslope when the wind died down, hitting the deck when it picked back up. He made it in under 17 hours.

[quote]It is difficult to get Babu to offer reasons beyond the mundane to explain why he decided to do the phenomenal things he did.┬áBut the most succinct reason he offers for his feats is this: ‘It gives me power.'[/quote]

With nothing to do and no one to talk to, we spend less than an hour at Base Camp. Up here, I’ve been lurching along like a wooden marionette whose master hasn’t yet mastered his art. As we prepare to go, I turn around and discover the undisputed champion of Everest standing on his head.

“Babu!” I blurt. “What the hell?”

The upside-down climber chuckles. “This is my Base Camp yoga.”

Ang Rita Sherpa┬álives in the village of Thamo, two hours up the trail from Namche on the ancient trade route to Tibet. Like Babu, he is a national hero in Nepal, but his glory days are over. Now in his mid-fiftiesÔÇöhe’s not certain what year he was bornÔÇöhe was the biggest Sherpa mountaineering star for the better part of a decade in the late eighties and nineties.

He retired three years ago, not because he could afford to stop working, but because he has serious health problems. “It’s my liver and my lungs,” he says, attributing his chronic illnesses to climbing without oxygen. When he’s not convalescing, he herds a few yaks and sits in his not-quite-finished guest lodge drinking chang, Nepal’s sour-tasting, grain-mash home brew, and offering up reminiscences about accomplishments that have already been eclipsed by the two Sherpas sitting in the room with him.

Joining Babu and me for our visit is Apa Sherpa, 41, who is as slim as Babu is stout. His presence makes this a minor historic occasion: Sitting around Ang Rita’s dining room are the only three men ever to have climbed Everest at least ten times. (Ang Rita and Babu have ten ascents each; Apa has 11.)

At one point I ask Apa if he knows that Babu intends to climb Everest twice this season, to get 12 ascents, which would leave them tied for the record if Apa summits once, as he intends to. “No, I didn’t know that,” he says quietly, offering a wan smile.

“Well, what do you think?”

“It’s no problem,” he says, with a nearly imperceptible shrug. “I don’t do climbing for myself, or for recordsÔÇöonly for clients.”

Babu does compete with the records of these men, and he has far outstripped them in the realm of self-promotion. Apa, who speaks proficient EnglishÔÇöcrucial to sponsorsÔÇöruns a lodge an hour up the trail in Thame but has so far been unable to leverage his r├ęsum├ę the way Babu has.

There are three ways for Sherpas to make money on the mountain. First, there’s salary. In return for humping loads, fixing lines, setting up camps, and carrying extra oxygen bottles for clients, a Sherpa earns between $7 and $10 a day. Second, when he signs on to an expedition he receives an “equipment allowance” of between $1,500 and $2,000; since many Sherpas already own a full complement of climbing gear, this often goes straight into the pocket. Third, Sherpas can earn bonuses for shuttling loads between camps and sometimes for helping clients summit. Add it all up, and a Sherpa might walk off with $4,000 for a couple of months’ work. An American guide, on the other hand, can make $20,000 to $30,000 leading clients on Everest.

Thus the perennial, seesawing quarrel among mountaineers over what’s fair pay for Sherpas. “Babu is risking his life to get people up there and not getting paid shit, really,” says Jared Ogden, an American climber who has twice hired Nomad Expeditions as his outfitter. “He’s not making what Western guides are making, and that’s grossly unfair.” The per capita income in Nepal is $210, goes the other side. “These guys are my friends, and I pay them well,” says veteran American climber and guide Eric Simonson. “I don’t buy in to the idea that Sherpas are poor and downtrodden. Some of them get paid top dollar.”

Either way you look at it, Babu is starting to chip away at the disparity in income, and I have never heard him complain about it. His real breakthrough was in striking a sponsorship deal with Mountain Hardwear for cash as well as gear. According to his current contract, he receives more equipment than he could ever use, plus $5,000 a year. And that’s not all.

[quote]A sherpa can make money three ways: salary, equipment allowance, and bonuses. They might make $4,000 for a couple months’ work, while an American guide can walk away with $30,000.[/quote]

Babu spent two months last summer doing entirely different work for his sponsor. In an extended guest appearance that thrilled both his supervisor and Babu, he earned $15 an hour working in Mountain Hardwear’s distribution center in Richmond, California, as a common laborer, stocking shelves, breaking down cardboard boxes, and cleaning up.

“I liken him to the Tiger Woods of mountaineering,” says Joe Stadum, Babu’s boss at the warehouse. “But you’d never know it, because he’s so quiet and calm. Most of the guys don’t have a great interest in climbing, but he was on the cover of our catalog, and they liked asking for his autograph.” According to Stadum, he showed up early every day and had to be asked to go home at night.

To Babu, there’s no irony here. “That’s good money,” he told me. “I don’t think because I’m famous I can’t do manual labor. I don’t see the connection.

“I make more than I do on Everest.”