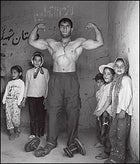

SO THERE’S THIS IRANIAN farmer, a great big strapping bodybuilder guy who lives in a tiny village high in the Elburz Mountains, and he’s working out in a makeshift gym, hoisting homemade weights made from five-gallon jerry cans filled with cement. I’m the first American Parviz Kiai has ever met, and he wants to shake my hand, despite the fact that my mission in Iran is to visit the castles of the Assassins, a radical Islamic sect that was, arguably, the first terrorist group in history. This is an endeavor some think unlikely to redound to Iran’s acclaim or glory.

Iran with a human face: wrestler Parviz Kiai flexes for his fan club.

Iran with a human face: wrestler Parviz Kiai flexes for his fan club. A grizzled mule driver from Garmrud.

A grizzled mule driver from Garmrud. The Elburz Mountains rise over Tehran.

The Elburz Mountains rise over Tehran. Shahram “Shroom” Yassemi leads the pack train out of Pichibon.

Shahram “Shroom” Yassemi leads the pack train out of Pichibon. High lonesome: a farmer and her mule near Alamut.

High lonesome: a farmer and her mule near Alamut. Greetings from Assassin country: the trekking crew leaves Sharestan.

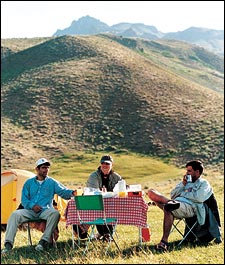

Greetings from Assassin country: the trekking crew leaves Sharestan. Kicking back in the Elburz: left to right, Shahram, the author, and Abbas Jafari meadow-camping at 9,000 feet.

Kicking back in the Elburz: left to right, Shahram, the author, and Abbas Jafari meadow-camping at 9,000 feet.No matter. Parviz motions to the wall of his gym, where there are several photos taped up on the adobe. Affixed highest is the grim and glowering countenance of the Ayatollah Khomeini, whose death in 1989 is mourned each year on an official national holiday called The Heart-Rending Departure of the Great Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Below the defunct ayatollah are dozens of photos clipped from American muscle magazines: huge, freakish steroidal monsters festooned with enormous and appalling dirigibles of muscles. It was, I thought, a wall of dueling Great Satans, an arresting graphic representation of Iran’s current identity crisis. It’s true that angry demonstrators in Iran’s capital, Tehran, had just been out in the street chanting “Death to America.” On the other hand, this is the same city that held a candlelight vigil after the September 11 attacks to express its sympathy and support for America. It’s the same nation that has voted overwhelmingly for political and economic reform in the past two presidential elections. But it’s also a place with a theocratic government that President Bush says is part of an “axis of evil,” a place where┬Śaccording to a U.S. National Security Council spokesman┬Ś”hard-line unaccountable elements…facilitated the movement of Al Qaeda terrorists escaping from Afghanistan,” and where “an unelected few…have used terrorism as an instrument of policy.”

It was the Assassins who pioneered the concept of terrorism as an instrument of policy back between the 11th and 13th centuries. Murdering prominent officials and clerics, of course, was nothing new. People have been whacking kings and emperors since the dawn of recorded history. But early-day assassination had usually been a one-time deal: a Brutus and some conspirators taking out a Caesar. The Assassins repeatedly and systematically killed their enemies with guile and stealth, striking them inside their own strongholds, and used the threat of imminent assassination to bend officials to their will.

In fact, the English word assassin is rooted in the name of the sect, and the Assassins, or so the legends would have us believe, committed their murders under the influence of hashish. They were called hashishiyyin, the Arabic word for hash smokers. The cannabis suggestion invariably generates skepticism among the ranks of those who have inhaled. Ruthless killers, honed to razor-sharp perfection, taking big hits off the bong? Kind of hard to picture.

It was Marco Polo who told their story best. His version of the Assassin legend goes like this:

The leader of the sect┬Śthe Old Man of the Mountain┬Ś”caused a certain valley between two mountains to be enclosed,” and this area he turned into a garden, with every variety of fruit, runnels of milk and honey and wine, not to mention “the most beautiful damsels in the world.” The Old Man, Marco Polo insists, fashioned the garden after the Islamic version of paradise, and “no man was allowed to enter the Garden save those whom he intended to be his Ashishin.”

Young men who became inductees were drugged during a meal, then fell into a deep sleep, and woke in the garden, “where the ladies and damsels dallied with them to their hearts’ content.” Drugged again, a young man woke this time in front of the Old Man of the Mountain, who would say, “‘Go thou and slay So and So; and when thou returnest my angels shall bear thee to paradise.'” That is, they’d get to live in the garden. And if the young man were to die in the assassination attempt, he’d end up in the other, heavenly paradise anyway. It was a kind of win-win situation for the medieval dagger-toting terrorist. “And in this manner,” Marco Polo states, “the Old One got his people to murder any one whom he desired to get rid of.”

This is a great story, lacking only historical veracity. It is more likely, as Bernard Lewis suggests in his 1967 book The Assassins, that orthodox Muslims, writing about a sect they found heretical, used the Arabic word hashishiyyin specifically because it was a term of popular abuse meant to ridicule people who behaved in an outrageous manner.

The story of the Assassins has always fascinated me, and I said as much on my Iranian visa application. There wasn’t much time to wonder if the mention of Assassins might prejudice my case, because the visa came through almost immediately, and I left for Iran a day later, before anyone could change his mind.

Abbas Jafari met me and photographer Rob “the Duck” Howard at the Tehran airport. Abbas, 40, was a guide and climbing pal of some American mountaineers who had helped make the introduction. He wasn’t physically imposing, not at first. He may have been five inches over five feet tall, and I doubt he weighed more than 135 pounds. But his hands were big and scarred, like a rock climber’s, and his wrists and forearms were huge. There was something about the guy.

“He’s a badass,” Rob said.

Little did we know.

LET’S SAY YOUR MOTHER HAS SUFFERED a terrible accident┬Śit doesn’t matter what┬Śand she is bleeding to death in the backseat of your car. The hospital is a 30-minute drive away. The streets are wide, two or three lanes in either direction, and they are filled sidewalk-to-sidewalk with slowly moving cars. It is the worst traffic jam you have ever seen in your life. Your mother has ten minutes to live. How will you negotiate these gridlocked streets as your mother’s eyes dull and death steals up on her?

That’s how everyone in Iran drives, all the time.

Tehran’s traffic is the most terrifying in the world, and simply crossing the street is an exercise in daring and judgment involving several very real life-and-death decisions all happening more or less instantaneously. Urban planning doesn’t exist: There are no underpasses or overpasses or pedestrian crossings. You just stroll out into the street and move into the laneless chaos of oncoming cars. Sometimes pedestrians gather along the sidewalk┬Śit doesn’t have to be at a crossing┬Śand then, as if on cue, they move boldly into traffic, 20 or 30 people at a time, challenging death as drivers attempt to intimidate their way through the herd.

Abbas grabbed my arm and maneuvered me into the rush of cars. It was the most frightening thing I did the entire time I was in Iran: cross the street.

We stopped in a teahouse to discuss the trip. First, we would drive to the vicinity of the Assassins’ castles, then later we’d trek over the mountains by way of Salambar Pass. Abbas spoke English with the precision of Inspector Clouseau, and at times his odd iterations approached poetry. At one point we paused to watch a defeated and mournful-looking woman walk by outside. “The lady,” he said, “is so sad eyes.”

The lady with the sad eyes reminded me that we would be traveling in the footsteps of the indomitable Freya Stark, one of the great travelers of the last century. Between 1930 and 1932, Stark explored Iran (then called Persia) and during her first expedition concentrated her efforts on finding the remains of the castles of the Assassins. Alone, and with very little money, Stark arranged for guides, for donkeys to carry her gear, and then she set off through the passes of the Elburz Mountains, looking for ruins in the place where terror was born.

In 1934 Freya Stark published her account of the journey under the irresistible title The Valleys of the Assassins. Her writing is witty, erudite, wonderfully descriptive, and suggests that she was a woman whose sense of humor served her well in the face of guns, official ineptitude, thuggery, and a few pesky deadly diseases. She was possessed of that uniquely congenial British ability to appreciate that the most appalling dilemma would eventually devolve into a rather amusing anecdote. She wasn’t plucky, not in the ordinary sense: Freya Stark was fearless and daring and courageous. T. E. Lawrence himself called her “a gallant creature.” Dame Freya Stark died a knight of the British Empire in 1993, at the age of 101. She is one of my heroes.

But why on earth would a brilliant woman choose to travel alone, in truly dangerous and fearful situations? Jane Fletcher Geniesse, author of Passionate Nomad: The Life of Freya Stark, gives us one hint. At the age of 13, Freya, visiting a factory in Italy, caught her long hair in a flywheel and was yanked viciously to the ceiling. An onlooking official, rather than cut the power, pulled her free by her ankles. She lost much of her hair, part of an ear, and her right eyelid in the accident. This disfiguring disaster colored Dame Freya’s life: She was, Geniesse declares, “never able to overcome a dread that she might not be attractive to the opposite sex.”

║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° the teahouse, a teenage couple strolled by, holding hands. Four years ago, Abbas said, you wouldn’t have seen that. Reform is measured in such matters. These days, for instance, women are not obliged to wear the head-to-toe tentlike garment called a chador. Government policy does, however, require that all women seen in public, even Western visitors, wear a scarf and a trench-coat-like affair called a manteau. Legs must be covered, but in a recent bit of giddy reform, women are now allowed to appear in public without socks. Some young women, I noticed, were pushing their new freedom: They were wearing sandals that displayed painted toenails.

Sixty-five percent of Iran’s population is under 25 years old. During the Iran-Iraq war, which started in 1980 and lasted ten years, more than 600,000 Iranians died; people were encouraged to have children. Lots of them. And they did. The teens and twentysomethings don’t remember the 1979 Islamic revolution that did away with the shah and his secret police, the SAVAK. They don’t remember the hostage crisis, in which militant Iranian students held 52 Americans from the U.S. embassy for 444 days. Young people want to listen to loud music and dance and go to parties. All the other kids are doing it. They know this; they see it every day on illegal but ubiquitous satellite TV.

So the government is being pushed toward reform by kids and by TV. It is said those who advocated reform were seduced by the fashions and the media of the West. They were “West-toxified.” I asked Abbas, who had switched from fighting in combat to guiding French folks and Italians and Germans and Americans, if he thought he’d been West-toxified.

During the revolution in 1979, he’d been an Islamic idealist, involved with a mosque school. Then he volunteered to teach soldiers mountaineering techniques. He served in the war with Iraq. Eventually he trained as a commando and worked for four years on the border of Pakistan, intercepting massive drug shipments. He spent some time undercover. Of the 24 men he trained with, 18 died.

In all, he’d spent eight years in the army. It wasn’t that Abbas was West-toxified; he’d just gotten tired of killing people.

AND SO THERE WE WERE, the next day, Abbas and Rob and I, packed into a new four-wheel-drive Nissan, barreling north down the road toward the valleys of the Assassins, while cars ahead of us and behind us and on all sides of us emitted whole blizzards of candy wrappers and half-eaten fruit and yogurt cartons and nutshells and sometimes even entire newspapers.

Abbas was in some distress about this. “Always,” he said, “I care about the garbage.”

There was a lot of it to care about.

Abbas’s assistant and our interpreter for the trip, Shahram Yassemi, 33, was staring out into the swirling storm of refuse in a small agony of embarrassment. Shahram is considered “Americanized.” He left Iran at 15 and studied at the University of Wisconsin, where he was known as “Sham,” “Shroom,” and “Shroomer.” Later he went to Oregon State University and studied forestry, which he didn’t like because “it was all about logging and road building.” Eventually he got a master’s degree in forest resources at the University of Idaho. Shahram wanted to use his knowledge to put together small-scale sustainable forestry systems in developing countries. He was generally proud of Iran and Iranians and was acutely sensitive about environmental issues.

“So, Shahram,” I said, as Reza, our driver, battered his way through flying apricot pits and pistachio shells, “your typical Iranian has a hard time differentiating between a public highway and a public dump site.”

“We definitely need some serious public education,” Shahram allowed.

“Hey, Duck,” I said to Rob. “Shahram thinks maybe they ought to have an anti-litter campaign. Here. In Iran.”

The Duck was dumbfounded. “You’re kidding.”

“Really. He thinks his fellow countrymen may actually be a bit profligate with their rubbish.”

“Profligate!” the Duck said. “Rubbish.”

“Hey,” Shahram said, “why don’t you guys bite me.”

Abbas was generally nervous about this kind of exchange. Courtesy was the convention in Iran. But Shahram had fallen in with American and Canadian skiers, with backcountry climbers and the like. In grad school he had spent a couple of winters living in his car (a $300 Toyota) and skiing at resorts like Crested Butte and Jackson Hole. His family hoped he might get a degree in engineering. Some kind of doctorate. Instead he was a grad-school ski bum and had become expert in the American outdoor tradition of giving the other guys a whole bunch of shit.

“So,” Abbas said, obviously changing the subject, “looking now seeing Elburz Mountains.” We were rising into a series of hot and spare and treeless hills. The grass was sunbaked brown. It was a kind of vertical and merciless Bakersfield, and it just kept going up: 6,000 feet, 7,000, 8,000. We came over the pass in the relative cool of the late afternoon. There was a river far below, the Shahrud, which looked, on my Iranian map, to run about a hundred miles, generally in an east-to-west direction. The land along its banks was a brilliant, nearly iridescent, green.

The valley below was prime Assassin country. The sect had had castles up all the drainages that fed the Shahrud, more than 50 of them in the area that was called the River Bank, or the Rudbar. The River Bank is set square in the middle of the northern Elburz and is protected from the plains to the south and east by mountains rising precipitously from the desert; it is also sheltered from the Caspian Sea, to the north, by a crest of craggy, glaciated summits.

We dropped to the rice paddies along the river. About 600 feet above, I could see the shattered walls of a castle undulating along the contours of the hillside.

Abbas got out and began climbing up a steep rock-strewn slope, and it became clear, on this first negligible jaunt, that Abbas and Shahram could climb circles around the Duck and me. The gravel field got steeper toward the summit, and we passed through stones piled where a gate might once have been. This was the Assassin castle of Lammasar.

The Assassin theology is highly complex, and the most simpleminded of explanations would be to say that it is all about succession. When the Prophet Muhammad died in 632, he left no clear instructions about who was to come after him. Abu Bakr, one of the first of the Prophet’s converts, was appointed ruler. A dissident group believed that Ali, the Prophet’s cousin and son-in-law, was the obvious choice. He was, in fact, the fourth caliph, or divinely appointed leader. But Ali was assassinated, and Husayn, his son and successor, was killed in the battle of Karbala.

As time progressed, the Islamic orthodoxy accepted the idea that the office of religious leader could be largely an elective one. The Party of Ali, the Shia, clung to the idea of succession through the line of the Prophet. Iranians are mostly Shiites and are sometimes called Twelvers because they believe there have been 12 imams, descendants of Ali, the last of whom is in hiding and is called the Awaited One.

The Assassins split with the Shia in 765, following the death of Ja’far al-Sadiq, the sixth imam after Ali. The group that was to originate the concept of organized political terror supported al-Sadiq’s eldest son, Isma’il, as imam. But the great majority of Shiites accepted Musa, Isma’il’s younger brother. And that issue┬Śwho was to succeed Ja’far al-Sadiq┬Śput the supporters of Isma’il in direct confrontation with Twelver Shiites.

The Ismailis were a reasonably successful sect for about 300 years, rising and falling in prominence. Sometime in the late 11th century, a remarkably able and frightening man named Hasan-i Sabbah reinvigorated the faith and, through stealth, took over the castle of Alamut, in the middle of the River Bank area. It was from this fortress, Alamut, that the Old Man of the Mountain sent out his Assassins.

As I pondered Islamic history on our climb to the castle, the Duck and Shahram exchanged an assortment of sarcasms, as Americans will. “I bet,” the Duck said, “you’ve never even seen your girlfriend’s hair.”

“No,” Shahram said, “but the chadors with the cutaway nipples are fun.”

The castle had been built into the ridgetop, but there wasn’t much left of it. The walls had once enclosed a space that Freya Stark thought to be about 1,500 feet by 600 feet. What we saw, at the north entrance, were thistles growing in a pile of rubble. There were several stone cisterns, large rectangular holes, one of them at least 25 feet deep, chiseled out of the solid rock: pools to supply the castle in the event of siege.

Marco Polo mangled the truth in his account of the Assassins, but it is a fact that Hasan-i Sabbah was the Assassin master and that he killed some of the most highly placed of his rivals. The initial victim was the vizier Nizam al-Mulk, the Turkish sultan’s chief counselor, killed by dagger blows on October 16, 1092.

“It was the first of a long series of such attacks,” writes Bernard Lewis in The Assassins, “which, in a calculated war of terror, brought sudden death to sovereigns, princes, generals, governors, and even divines who had condemned the Ismaili doctrines.”

The prime tactic was to place an agent, an assassin, in the target’s retinue. Sooner or later, a sultan would ask a stable hand what he thought of a horse, and the answer might be a dagger to the heart. The weapon was always a dagger, and the assassin seldom escaped with his life. No potentate was safe. Many felt it necessary to wear chain-mail shirts at all times.

At the lower, southern end of the castle, there were several nearly intact walls, along with a few turrets and towers. The terrain below was steep enough that a rider would have to lead a horse. A soldier on foot would strain toward the wall, stumbling with his weapons. I stared at a broken tower and the crumbling ramparts built into the sinuous bend of the slope and could see, for a moment, the terrible symmetry that was Lammasar. The castle was absolutely impregnable. It could not be taken, ever, by anyone.

The wind had sprung up, and it whistled through the rubble, as if to emphasize the complete devastation on all sides. There was a lesson here, moving with the wind through the rubble. We camped that night near a small lake, and Abbas moved about, picking up litter here and there, but there was almost more trash than grass.

“Always,” he said, “I care about the garbage.”

“Then how come,” I asked, “we’re camped in a dump?”

Abbas said, “Is campsite.”

“He’s giving you shit,” Shahram explained.

“I see,” Abbas said, but he really didn’t get it at all.

THE BEST STORY WOULD BE that the Mongols, having lost a few officials to Assassins, set out to destroy the sect and, with it, the very concept of terrorism. The fact is that the grandson of Genghis Khan, H├╝leg├╝ Khan, who wished to be called the World Conqueror, had already subdued most of Turkey and southern Persia before he took on the Assassins, entrenched as they were in their mountain fastness. The supreme leader of the Assassins in the year 1256 was Rukn al-Din Khurshah, who had installed himself in the unconquerable cliff-face castle called Maymun-Dez.

The Persian historian Juvayni, whose job it was to glorify H├╝leg├╝, describes the Mongol advance on Maymun-Dez: “They set out…like a flood in their onrush and like a flame of fire in their ascent; and their horses’ hooves kicked dust into the eyes of Time.”

Maymun-Dez was formidable, no doubt about it. We had walked up to it through the village of Shamskalayeh, a jumble of adobe houses, where old men stared at us from glassless windows. As we ascended, the trails degenerated into goat tracks and then disappeared, and I found myself crawling on all fours. Abbas and Shahram took the hill upright, kicking dust into the eyes of Tim.

Presently we arrived at the base of a vertical rock wall. There was some beige plaster stonework on the face of the red rock, and I could see a number of caves set about halfway to the summit. Abbas had climbed up there a few times. These caves, he said, had been carved out to form enormous rooms, and then more rooms on top of rooms, which must have been connected, one to the other, by wooden ladders. A spring near the summit of the cliff fed water to the castle. From where I stood, at the base of the cliff, I could see a man-made walkway between the two largest cave rooms. Abbas wouldn’t hear of a climb to the caves: We had no ropes, and he himself wouldn’t go into those echoing rooms ever again. The caves were collapsing up there.

In November 1256, the Mongols laid siege to Maymun-Dez. They confounded the Assassins with their new and terrible weapons technology. The kaman-i-qav was a huge crossbow-like device capable of firing flaming javelins well over a mile. Juvayni relates that “of the devil-like Heretics, many soldiers were burnt by those Meteoric shafts.”

Rukn al-Din surrendered and sought terms from the Mongols. H├╝leg├╝ ordered him to command the surrender and destruction of all the remaining Assassin castles. Most garrisons obeyed. After Rukn al-Din had served his purpose, he was “kicked to a pulp then put to the sword.” The castles were looted and systematically destroyed. All the captured Assassins were to be executed. One source estimates the number of Ismailis killed at 100,000. As Juvayni put it: “Of him [Rukn al-Din] and his stock, no trace was left, and he and his kindred became but a tale on men’s lips.”

In fact, there are Ismailis today, mostly centered in India, Pakistan, and cities on the Indian Ocean, and their spiritual leader is the present Aga Khan. The Ismailis are among the most pacific and tolerant sects in Islam. Many of them are shopkeepers in Bombay.

Back in the days of the Assassins, however, Alamut, the castle of the feared Hasan-i Sabbah, was the headquarters of the sect. It wasn’t far from the castles we’d already seen, but unlike Lammasar or Maymun-Dez, there were road signs all the way. Set on a massive knob of rock that Freya Stark said looked like the bow of a ship seen from the side, Alamut rises 800 feet above the town of Gazorkhan, which was bustling with foreign visitors.

In the past few years, Alamut has become a tourist destination. There was a series of excavated steps leading to the top of the ship rock. The path plunged through a tunnel of stone and emptied out onto a narrow ridge where there were broken turrets and tumbledown walls and a number of cisterns carved out of the solid rock. The Iranian Cultural Heritage Department was restoring some of the walls and towers.

There was no place that might have been a heavenly hashish-fired garden. If the fabled paradise ever existed, it must have lain below, in Gazorkhan, probably next to the bus station┬Śall in all a rather rinky-dink heaven on earth. Bernard Lewis, in assessing the Assassins’ place in the history of Islam, assures readers that the movement was regarded as a profound threat to the existing order, but what he finds most significant is “their final and total failure. They did not overthrow the existing order; they did not even succeed in holding a city of any size.” And their followers, he notes, “have become small and peaceful communities of peasants and merchants.”

That is the lesson of the castles.

IN GARMRUD, where the Shahrud pours out of the mountains, we rented some mules and prepared to take a run at the peaks, moving north, over passes that rose to 10,000 feet, before dropping to the Caspian Sea, the world’s largest lake, at 92 feet below sea level. We were following, more or less, in the footsteps of Freya Stark.

While Abbas negotiated for mules, the Duck and I spoke with a variety of locals. They’d seen any number of Europeans before, but they’d never met any Americans, a fact that made us momentary celebrities. Did we like Iran? Had we been treated well? We answered in the positive. The men shook our hands and then, in what I found to be a singularly emotive gesture, placed their right hands over their hearts.

The mules, three of them, were loaded, pulled along by two boys, one about 14, the other a few years younger. We set off walking along the Shahrud, through a canyon of towering rock. We were strolling along a dirt road, newly built and as yet unopened. Suddenly a purple Paykan, the Iranian national car, a kind of failed Fiat, sped past. The driver must have skirted the roadblock below. He slammed on his brakes and nearly backed into us. There was a brief, argumentative negotiation with our young mule drivers. The driver of the purple Paykan and the four people with him wanted to rent our mules, which were the last ones available in Garmrud. The driver didn’t care what we had paid, he’d double the price. The boys, to their credit, refused.

Abbas turned off the road, and we began rising into the Elburz at the seriously aerobic and slightly hysterical pace of more than 1,000 vertical feet an hour. We negotiated a number of cruel switchbacks and scree slopes until, about 2,000 feet above Garmrud, we arrived at the village of Pichibon, whose name means “the end of the switchbacks.” There were a few adobe homes, and some men in cowboy hats loading mules. It had a kind of American Southwest flavor to it, except that all the women were dressed modestly in approved Islama-wear instead of turquoise and denim. One of them asked us if we had seen her relatives on the trail. It became clear that these were the people in the purple Paykan who had tried to buy the mules out from under us. Shahram said we’d seen them, and they needed mules. Two boys and four mules were dispatched to pick them up.

We camped in an enormous grassy meadow at about 9,000 feet. Spread out on all sides of us was the unexpected splendor of the Elburz Mountains, rising in this neighborhood to more than 12,000 feet. Glaciers glittered on the shoulders of the highest peaks; it was an entire Switzerland of show-offy, snowcapped summits.

Abbas cooked a dinner of rice and canned stew, then tried to pile my plate, and the Duck’s, completely full, leaving almost nothing for himself or Shahram. This is a kind of self-abnegating variety of well-mannered courtesy so common in Iran that it has a name: ta’arof. Over the past week, it had become clear that unless we absolutely refused extra food, the Iranians would never eat.

“No,” I said to Abbas. I said it three times, until Shahram said, “Don’t ta’arof.”

“I’m not ta’arofing,” I said. “You’re ta’arofing.”

“Am not,” he said, both of us ta’arofing our asses off.

THE NEXT DAY SHAHRAM, the Duck, and I climbed a modest mountain nearby. I suppose it was somewhere near 11,500 feet high, a little more than 2,000 feet above our camp. Shepherds we met along the way called it Mam Ruzu. The face was a forbidding wall of overhanging crags and vertical columns and crumbling rock. The climb was potentially deadly and required great skill, not to mention near-imbecilic audacity.

So we walked up the sloping back side, among sagelike flowering bushes watered by the snowmelt from a few late drifts. Snow-crested mountains soared all about and the sun reflected off the glaciers like so many mirrors. We summited, then found a way down on the east side of the face, skiing in our boots through steeply sloping scree fields that led eventually into decorative and absurdly ornate fields of wildflowers. There were yellow buttercups and purple and white flowers I couldn’t identify, interspersed in various swirling patterns. I saw there the elements of complex design so appealing in Persian rugs or in the tile work of various mosques.

It was still several miles across a vast marshy meadow to camp, and when we dropped over the lip of an undulating swale, six or seven huge shaggy dogs, each weighing in excess of 100 pounds, surrounded us. There were a lot of teeth in evidence, and perhaps a thousand sheep and goats grazing nearby. A shepherd shouted a command and the dogs dispersed, grumbling among themselves. Many of them, I noticed now, were pretty banged-up. They walked with an assortment of limps.

The dogs were a kind of sag gorg, a wolf dog, and some wore thick leather collars with metal studs on them, because wolves always go for the neck in a fight.

“How many times a year do they fight the wolves?” I asked.

“Five or six times a night,” the shepherd said. It seemed an implausible number to me, but then again, it did explain why half the dogs were limping.

Later we watched seven shepherds milk their animals, all in a chaos of dust and finely organized confusion. Shahram translated a few questions back and forth. Later, on the way back to camp, Shahram said, “You are the first Americans they have ever seen. They wanted to know how relations were between our countries.”

“What did you tell them?”

“Could be better. I said that you guys came to meet the people and see the culture here. I said that was good, because the image Americans have of Iran is all desert and camels and terrorists. I said what you were doing would help ignorant people.” We walked on a bit. “Of course I was bullshitting.”

“Actually,” I said, “you weren’t.”

AS WE MADE OUR WAY over Salambar Pass and began the long drop down along the Seh Hezar River, I asked Abbas how he’d started climbing. In school, he said, a teacher noticed he had talent as an artist and gave him a set of watercolor paints. He used to go into the mountains to work and eventually the paints fell aside. He started climbing, and he got good at it.

His skills were valuable in the 1980s. Abbas taught soldiers survival during the Iran-Iraq war. He clearly didn’t like to talk about the combat, but I asked. Sometimes, he said, it was too easy. The enemy would be camped under a cliff, thinking they were sheltered, but the Iranians could simply rappel down the cliff faces and slaughter the Iraqis in their sleep. Somehow, Abbas’s idealism began to fade.

“What changed you?” I asked.

“Ah, es-slowly is coming the hard questions.”

There were many things that contributed to the transformation. Abbas said he’d go through a dead Iraqi’s pockets and find pictures of the soldier’s family, his wife, his children. “I think: He is a man, like me,” he said. “I don’t want to kill.” He paused and added, “My government going one way. I going different.”

Then there were the people he’d guided, or met climbing on his own journeys. Abbas has a globe in his home, and he looks at it often. He points out to himself the countries where his friends live. Now, he said, in his fractured and poetic English, “I am more interested in relations between people.”

“Did you know,” I said, “that today is the independence day of my country?”

Abbas stopped, shook my hand, then placed his right hand over his heart in that gesture I always found so curiously affecting. It was the only time on the whole trip I saw him do it.

We came up over the pass and looked into a huge green amphitheater, entirely treeless, entirely green. It seemed to curve around us for 10 or 20 miles in either direction, and Abbas said, “Next year is coming road.” The road, being built now, would bring electricity to the small villages on this ancient trail from the valley of the Shahrud, over Salambar Pass, and down to the Caspian Sea.

“Is sad,” Abbas said. “But they need.” Last year, he told me, a lady took ill and died on the donkey ride down to the road. “So they need.”

I suppose. Still, it was impossible to look at the vast curve of earth funneling down into a river gorge and not grieve for the land. “I sad,” Abbas said, “because maybe somebodies, he have a picnic.”

And I saw the world clothed in rubbish from horizon to horizon, as Abbas did at that moment. “Always,” Abbas said again, “I worry about the garbage.”

Just below the pass, in the town of Salange Anbar, we met Parviz, the weight lifter who’d decorated his wall in photos. The trail broadened after Salange Anbar, and we followed it down the Seh Hezar to a paved road where we took a bus to the Caspian Sea resort town of Ramsar. The world’s largest lake looked gray and dismal in a stiff wind. Women were required to dress modestly, in chadors or manteaus, which took some of the joy out of the beach experience.

Two days later, back in Tehran, we attended a party at an apartment owned by a man named Ali, a friend of Abbas. We ate various fruits and discussed the state of adventure, such as it was, in Iran. The whole concept of the recreational use of the backcountry was so new in Iran that the men present liked to joke that they had fathered the entire idea. Abbas was “the father of Iranian climbing.” Shahram was the “father of Iranian telemarking.” A man named Kazem Bayram, whom I knew to be one of the best breath-hold divers in the world, was the “father of Iranian diving.” Ali’s wife, who was scarfless and dressed in a sleeveless blouse┬Śwomen are required to cover up only in public┬Śsaid that she was the “father of sitting around worrying about these idiots when they’re gone.”

The day I got home, President Bush gave a speech praising reform in Iran, a move that predictably provoked new “Death to America” demonstrations in the streets of Tehran. Change comes slowly, world peace is a good thing, and I’d just as soon all terrorists joined the Assassins, of whom, Juvayni gleefully wrote, “no trace was left.” I was doing my part, as I saw it, buying every muscle magazine on the stands and mailing them off, as promised, to a bodybuilder in the mountain village of Salange Anbar. I think Freya Stark would have approved, and it was, after all, the least I could do for my new pals, the fathers of Iranian adventure.