November 10, 2004

Nepal

“Kathmandu Under Siege.” “Bombs Close Luxury Hotel in Nepal.” “Nepalese Struggle to Break Rebel Hold on Capital.” These were just a few of the ominous headlines in the international press this past summer after several bombings rocked Nepal’s capital city of Kathmandu and Maoist rebels threatened attacks on traffic headed to the Kathmandu Valley. “Sounds terrible, doesn’t it?” says Ravi Chandra Hamal, 49, CEO of Ama Dablam ���ϳԹ��� Group, a tour operator headquartered in Kathmandu. “But it wasn’t true. It was really alarmist, hysterical media coverage.”

Well, maybe. But hyped by the press or not, last August and September were rough in the mountain kingdom. And, as a bloody November 9 bombing of a government building indicates, the danger remains very real.

Things were looking particularly bleak this past summer. Over the course of a month, beginning in mid-August, alleged Maoists threw pipe bombs onto the tennis courts of Kathmandu’s five-star Soaltee Crowne Plaza Hotel, rebels announced plans to attack traffic on its way to the Kathmandu Valley, forcing the army to provide armed escorts to shuttle food and supplies into the capital for a week, and angry mobs numbering in the thousands trashed downtown mosques and looted Muslim-owned businesses to protest the execution of 12 Nepalese citizens by Islamic militants in Iraq. On September 10, just as life appeared to be limping back to normal, suspected Maoists lobbed two pipe bombs over the wall of the American Center, which houses the U.S. Embassy’s public affairs office, along with the American library and the Fulbright educational foundation. There were no injuries, but the attack—the first against a Western diplomatic target—combined with the previous violence, prompted the Peace Corps, for the first time in its 42-year history in the country, to withdraw all volunteers.

Nepal’s adventure travel industry—already hobbled by a U.S. State Department advisory warning American citizens to avoid all non-essential travel to Nepal since October 2003—was devastated. Tour and hotel bookings for fall, Nepal’s high tourism season, initially plummeted. American arrivals alone dropped 21 percent in September as compared to the same month in 2003, and several international airlines suspended flights to the country. “I was pulling out my hair,” says a leading Kathmandu-based tour operator who suffered a number of cancellations in the aftermath of the unrest. “Clients were terrified to travel to Nepal.”

Of course, Nepal has been through all this before. Since the Maoists launched their armed insurrection in 1996, some 10,000 have died in the violence and periodic flare-ups have sent tourism numbers spiraling downward. The year 2001 was particularly rough: The country saw massive strikes as well as the assassination of nine members of the royal family by Crown Prince Dipendra (who then killed himself), which led to a dramatic drop in travelers to the country. But especially hard for outfitters this time was the fact that 2004 had started off so well, with a 26 percent rise in tourist arrivals in the first six months as compared to the same period the year before.

The good news is that Nepal’s travel industry may be getting better at bouncing back quickly. ���ϳԹ��� travel outfitters canvassed in October and early November (before the November 9 bombing), claimed they might actually be able to salvage the fall trekking season. Bookings were rebounding and Thamel, Kathmandu’s tourist hub, has been hopping. “November doesn’t look that bad,” says Basant Mishra, 51, president of the Nepal Association of Tour Operators. “We had a lot of cancellations, but now they have reinstated.”

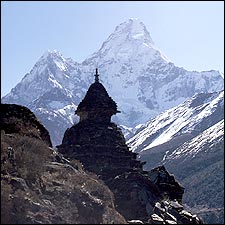

High-altitude mountaineers are also learning to take Maoist flare-ups in stride. Several major commercial guiding companies surveyed for this article reported zero cancellations for fall expeditions. Elizabeth Hawley, the 81-year-old mountaineering matriarch who has been meticulously documenting Himalayan climbs since 1963, says she’s been as busy as ever and estimated that more than 400 climbers were on 22,494-foot Ama Dablam in October.

As has been the case for several years, some of the most popular trekking areas, such as the Khumbu Valley leading up to Everest, and the Mustang plateau and Manang Valley north of Annapurna, remain Maoist-free. And even if you do run into them elsewhere, the threat continues to be to your beer money, not your life. On sections of the popular Annapurna Trail, where Maoist encounters with trekkers have become standard, the rebels demand a 1,000-Rupee (US $13.64) “tax.” Once paid, travelers receive a receipt—stamped with the likeness of Karl Marx, Vladmir Lenin, and Chairman Mao—to prevent them from being stopped again. (The fee can rise to $100 or more in the remote, far western regions of Dolpo or Humla.) The fact remains that not a single foreigner has been kidnapped or killed as a result of the eight-year-old insurgency. During that time, the country has received more than three million visitors. “The risk of being a victim of Maoist violence is clearly much lower than the risks of going trekking, mountaineering, rafting, or simply going in a bus,” says Keith Bloomfield, 57, the British Ambassador to Nepal. “The threat is fairly small.”

That might be true, but the bombing of the American Center raised the specter of U.S. citizens traveling in Nepal becoming targets. The Peace Corps still has no plans to return anytime soon. “The risk was no longer acceptable for us,” says a high-ranking Peace Corps official.

Insiders in the travel industry argue that such a change in Maoist strategy is highly unlikely. “They don’t have the mind-set to harm tourists. If they did, they could have certainly done it by now,” says Ama Dablam’s Ravi Hamal, a 24-year adventure travel veteran. “Tourism is the lifeblood of this country. Even the Maoists realize that.”

So far this fall, it seems Hamal is right. Mark Van Alstine, co-owner of the Colorado-based outfitter KE ���ϳԹ��� Travel, which specializes in trips to Nepal, says his groups haven’t had any trouble on 23 trips to Khumbu, Mustang, and Manaslu. “We planned our trips to run in areas we are comfortable with,” he explains. “We have not had any problems at all.”

Wally Berg, a 49-year-old American climber who runs Alberta-based Berg ���ϳԹ���s International, echoes that sentiment. “Business is booming in the Khumbu,” says Berg, who led a group of 11 clients to the Everest area in October.

It’s still too early to tell how the spring 2005 trekking and climbing seasons will proceed, and many outfitters are in a holding pattern. As for mountaineers, early indications point to another busy year for expeditions on Everest. Todd Burleson, owner of Alpine Ascents International, says he’s already filled the slots for his company’s spring climb of the world’s tallest peak. And Eric Simonson, co-owner of International Mountain Guides (IMG), reports that he already has enough sign-ups to carry on with all his spring Khumbu trips.

Still, if the November 9 bombing is the beginning of another spike in violence, the entire season, if not the entire country, could be thrown out of whack. “We have noticed that the word ‘peace’ is very, very important,” says Basant Mishra. It’s anybody’s guess at this point whether the Maoists will ever give it a go.