It’s an auspicious day in the Himalayas. I haven’t consulted a Buddhist astrologer to confirm whether it’s officially auspicious in the traditional sense of the word, but good omens are everywhere. The sun blazes in a cerulean sky, the distant peaks sparkle like diamond-studded snow cones, and I’m speeding through the Bhutanese countryside in a bus piloted by a driver named Danbahadur who tackles the 20 S-curves per mile like a seasoned NASCAR racer.

Bhutan

The fortress of Trongsa Dzong; right, the Zhiwa Ling hotel

The fortress of Trongsa Dzong; right, the Zhiwa Ling hotelBhutan

Children in Ngalhakhang; right, a boy in a gho

Children in Ngalhakhang; right, a boy in a ghoBhutan

SPIRITUAL PATH: Students on the road to the town of Trongsa.

SPIRITUAL PATH: Students on the road to the town of Trongsa.Bhutan

REVERENCE POINT: Trongsa Dzong monastery; left, its head monk.

REVERENCE POINT: Trongsa Dzong monastery; left, its head monk.Bhutan

But something feels a little off. It’s only my third day in the world’s last independent Tibetan Buddhist kingdom, and I’m already getting cultural whiplash from the ping-ponging yin-and-yang

Then there are the penis paintings. As the bus rolls by Wang’s Wood, a small mom-and-pop sawmill on the banks of the Paro River, we pass a ten-foot phallus rendered in impressive detail on the

I’m contemplating these juxtapositions when Danbahadur slams on the brakes and politely yet urgently asks us to disembark. I assume we have a flat tire or engine trouble┬Śa bad omen! But I soon realize that all the other vehicles on Bhutan’s only major highway have also come to a stop.

Robert A. F. Thurman, the spiritual guru of our eclectic crew of 23 international travelers, isn’t sure what all the fuss is about. The 64-year-old is slightly hard of hearing and has had his head buried in a Tibetan meditation book, practicing what he calls the “ultimate tolerance of cognitive dissonance”┬Śin Bobspeak, to be here and not be here at the same time. But Thurman is a veteran road-tripper and knows how to go with the flow.

“OK, campers, off the bus!” he shouts cheerfully, following the example of our logistical leader, 48-year-old Brent Olson, who is shooing people off the twin vehicle that holds the rest of our group.

@#95;box photo=image_2 alt=image_2_alt@#95;box

In addition to being this tour’s head “psychonaut”┬Śa term Thurman coined to describe a person on an extreme inner journey┬ŚTenzin Bob (as his friends call him) is also chairman of the religion department at Columbia University, author of nine books, the first Westerner to be ordained a Tibetan Buddhist monk, a close friend to His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and father of Hollywood superstar Uma.

A self-described “Buddhaholic,” Thurman is in Bhutan teaching the dharma, leading daily meditations, and providing one-on-one guidance as part of a two-week, $6,395 crash course in Buddhism offered by San Francisco┬ľbased luxury outfitter Geographic Expeditions. For travelers, it’s a doubleheader of enlightenment: We get inside the remote and mysterious “It” destination of Himalayan adventure, while at the same time exploring our inner frontiers under the tutelage of a man who’s been called the Billy Graham of Buddhism.

As we wait for the traffic to ease, a few of us wander to a bridge over the confluence of the Thimphu and Paro rivers. I’m so stir-crazy from sitting in a bus all day, I’m half tempted to cannonball into it, just for the sheer joy of being in a place where the rivers run wild and free.

Lily Bafandi, a forty-something Swiss investment banker with flowing blond hair and an orange bindi dot between her eyebrows, has unplugged from her iPod playlist of spiritual mantras and stands mesmerized by the churning waters.

“Is this the Stream of Consciousness?” asks David Bullard, a psychologist from San Francisco, interrupting our reveries.Before either of us can respond, Olson shouts, “The royal family is coming! The royal family is coming!”

Sure enough, 30 seconds later the royal caravan┬Śan entourage of police jeeps and five black Land Cruisers┬Śspeeds by. The bespectacled 50-year-old Royal Majesty Jigme Singye Wangchuck sits in the backseat of the lead SUV, followed by his four wives, all sisters, each in her own vehicle. We eventually learn that the family is on its way to the remote village of Ha┬Śthe king has drafted a new constitution, and he’s visiting every outpost to hash over the document with his subjects. Snapping photos is prohibited, but in my nanosecond glance I surmise that the king is definitely a looker.

Hours later we reach Dochu La, a Himalayan pass festooned with multicolored prayer flags. On a clear day, it’s possible to see 200 miles of summits from this 10,000-foot-high vantage point. Today doesn’t disappoint: The peaks expand to the east and west like a giant rammed-earth fence keeping the rest of the world at bay.

Tim DeFour, a 38-year-old real estate developer from San Francisco, takes in the view. “It’s so nice to be in a place where things are real and not just a Disney version,” he says.

But in this enigmatic little kingdom, I’m thinking, the real and surreal are one and the same.

OUR WELL-HEELED POSSE is a wild bunch, ranging in age from 28 to 76. It includes a Russian entrepreneur and his wife; a Wells Fargo bank veep; an Internet exec; an aspiring novelist and self-described “beach-bum philosopher” from Oahu; a brother-sister duo from Nevada and Manhattan; a 42-year-old day trader who splits her time between Santa Monica and Bhutan (yes, you can get a work visa if you invest in the local economy under various criteria); and miscellaneous other high-octane spiritual seekers. Some, like Linda Colnett┬Śa 63-year-old artist from San Francisco who recently lost her husband to cancer┬Śare in search of healing. Others are ticking off another country on a life list of nation bagging.

The physical well-being of this band falls squarely on the shoulders of co-leader Olson, a bearded, blue-eyed Californian who, owing to years of meditating or just plain niceness, refuses to come

Thurman lives in Manhattan, where he splits his life into a million little pieces, teaching two classes per semester at Columbia; keeping track of his five children and five grandchildren; traveling to his meditation center, Menla Mountain Retreat, in the Catskills; and overseeing his pet project, Tibet House, the Manhattan institution he cofounded in 1987 with actor Richard Gere and composer Philip Glass to preserve Tibetan culture. (Each person on this tour was asked to donate $1,100 to the organization, in addition to the trip fee.)

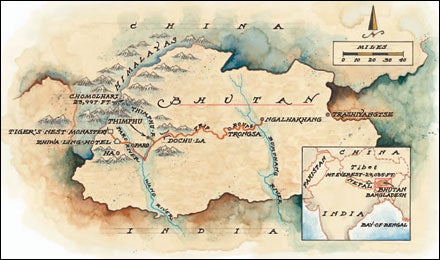

As a major-league Buddhist scholar, Thurman is in constant demand, and these days so is Bhutan. An oasis between India and Tibet, it’s one of Asia’s trendiest destinations┬Śat least for travelers who can afford the minimum $200-per-day tariff, which buys you a visa, transportation, and basic lodging.

After watching the cultural and environmental decay that took place in nearby Nepal, which has historically catered to the $5-per-day backpacker crowd, Bhutan chose a different path┬Śrestricting visitors to only those who can pay mightily for the pleasures of paradise. At this point, those pleasures come in four basic flavors: a vehicle-based cultural tour; a high-country trek on one of 13 government-approved routes; an on- or off-road cycling tour; or a whitewater adventure with one of the handful of outfitters who have begun to explore the country’s endless network of rivers. Whatever visitors choose, they must be accompanied full-time by a certified guide. In Bhutan, there’s no such thing as DIY.

The strictures haven’t hurt the nation’s cachet. In 2005, a record 13,643 tourists flocked in, thanks in part to the recent openings of two five-star resorts in the nirvana-like Paro Valley┬Śthe Uma Paro, a beautifully renovated $500-per-night, 29-room lodge; and the austere and elegant $900-per-night, 24-suite Amankora. This was a 47 percent increase from the year before and an ungodly number of chilips for a Switzerland-size country of about 800,000 that, until the sixties, barred almost all outsiders and had few cars or paved roads, no nationwide school system, very little health care, no national currency, and a barter economy.

@#95;box photo=image_2 alt=image_2_alt@#95;box

But a lot can happen in four decades, especially if the country is ruled by an enlightened being. His Majesty Jigme Singye Wangchuck has presided over Bhutan since 1972, when, at age 16, he became the youngest monarch in the world. In his 34-year reign, King Wangchuck has pulled Bhutan out of the Middle Ages, expanding a 2,700-mile road system and providing universal health care and free education. Subsistence farming is still the mainstay for about 90 percent of the population, but the nation is enjoying more prosperity and modernity than ever before. In 1999, the king legalized Internet use and television viewing (Bhutan was the last place on the planet to permit the latter), allowing satellite dishes to sprout on rooftops in the remotest villages.

There are three screaming headlines about the fourth royal Wangchuck: First, his four gorgeous wives live in separate residences in the most fashionable neighborhood of Thimphu, the capital city, while the king himself lives in a humble log cabin outside of town, to maintain the privacy he craves. Second, the devout Buddhist was once a fanatical basketball player, but he has recently switched his loyalties to golf; and third, in the late eighties, he dreamed up one of the most revolutionary concepts in contemporary world politics: gross national happiness.

Quantifying human happiness is an elusive project, but the king framed it around four steadfast pillars: environmental preservation, cultural promotion, economic development, and good governance. So instead of billboards advertising real estate deals or cheap cell-phone plans, Bhutan’s public ad spaces are consumed by slogans like “Feel the environment,” “Love nature,” and “Trees are deep, dark, and lovely.”

By law, the nation must maintain 60 percent of its land as forest, a mandate that the king holds inviolable. To protect the high country, mountain climbing is banned. As for fishing, catch-and-eat is frowned upon. Selling tobacco products and using plastic bags (which cause litter) are also forbidden.

“The king is way ahead of his time,” Bruce Bunting, a vice president at the World Wildlife Fund, told me. “National parks and reserves cover 26 percent of the country. Bhutan is the last place in the Himalayas where you have continuous forest cover┬Śand the only place on earth where tigers coexist with snow leopards.”

The most obvious evidence of cultural promotion, the second pillar of happiness, is the requirement that every Bhutanese man, woman, and child wear traditional dress, which they can accessorize as they please. For females, that means a kimono-like kira┬Śa hand-woven ankle-length dress often paired with high heels. Males wear a knee-length bathrobe-type outfit called a gho, which they usually pimp out with argyle socks, a baseball hat, and shades. The dress code is lifted on weekends, which makes designer jeans a coveted import.

Ancient traditions still hold sway, but the 21st century is gaining ground. Bhutan’s economic revenues are expected to surge in 2006 after a $900 million India-financed hydroelectric plant on the Wangchu River begins supplying power to northern India, for which Bhutan can charge hefty fees. In Thimphu, construction crews are putting the last touches on a brand-new five-star Taj hotel.

Even the Buddha is getting in on the action: To commemorate 100 years of the Wangchuck dynasty in 2007, Bhutan approved the building of a $20 million, 169-foot bronze statue of the enlightened one┬Śthe largest in the world┬Śon Thimphu’s outskirts.

The most ironic step the king has taken toward fulfilling his good-governance goals was his recent announcement that he’s quitting. Last December, after spending four years devising a new 34-article constitution, which he posted on the Internet so that citizens could offer comments, he proclaimed to a crowd of 8,000 in the far-eastern village of Trashiyangtse that he will abdicate the throne in 2008 to his Oxford-educated son Jigme Khesar Namgyal Wangchuck. If all goes according to plan, the crown prince, now 26, will lead the country’s transition from a monarchy to a parliamentary democracy. His Majesty’s announcement came as such a shock to his subjects that many of them wept at the news. But his strategy was simple. “The best time to change a political system,” the king told the gathering, “is when the country enjoys stability and peace.”

IT’S NOT HARD TO ENJOY peace when you’re standing in the afternoon sun on a rocky promontory looking toward 23,997-foot Chomolhari, the sacred “Divine Mountain of the Goddess,” a peak that hasn’t been scaled from the Bhutan side since 1970, owing to the national ban on climbing. Behind me is Tiger’s Nest, the 300-year-old monastery where, in a.d. 748, Guru Rinpoche, the saint who brought Buddhism to Bhutan, is said to have flown in on the back of a tigress and meditated in a cave for three months. Considering that we’ve just hiked three sweaty hours to reach this famous compound, which looks as if it were plunked down by a divine hand on an uninhabitable, 3,000-foot-high cliff, a visit by a flying tigress doesn’t seem out of the question.

Since foreign visitors need special permission to enter Tiger’s Nest┬Śthe home of about 60 monks, many of whom look no older than 12┬Śwe’re waiting in the walled yard for the rest of the group before we enter the temple. Olson does a head count. There’s one person missing.

“Where’s Lily?” asks Thurman.

It’s no surprise that Lily is AWOL. The ultimate 21st-century pilgrim, she not only brought her iPod mantra playlist but also lugged two suitcases full of brilliantly colored outfits that she matches to her mood of the day. In between bouts of wanderlust, which have taken her from India to New Mexico to study with famous gurus, she lives in a house in Z├╝rich and hosts revered leaders like the Dalai Lama.

After a bit, someone spots her glowing blond hair high up on a mountainside. She’s bushwhacking her way toward us across the slope. Olson dispatches a Bhutanese guide to fetch her, while the rest of us filter in.

The dank, cool space is an assault on the senses, like entering somebody else’s dream halfway through. Flickering candlelight throws shadows on giant clay Buddhas painted a shimmering gold and lined up behind the altar like benevolent sentinels. On every wall are murals of Buddhas entwined with their consorts in tantric embraces, and the altar is flush with plastic flowers, tarnished coins, butter sculptures, and food offerings. Through the open window, horns bellow from a distance . . . until they’re drowned out by the insistent ringing of a cell phone.

While the rest of us glance at one another, wondering how much bad karma comes with improper cell-phone etiquette within earshot of a Buddhist temple, Milissa Tranovich, the day trader┬Śwho’s been standing near the doorway┬Śhurries back outside to quiet her phone. The call, it turns out, is from a Bhutanese government official Tranovich met while playing golf at the country’s only course.

Lily still hasn’t surfaced, so the rest of us sit, close our eyes, and begin the hourlong meditation.

“Think of being in a high, free zone, visualizing the enlightened beings above you,” says Thurman. “If you’re not Buddhist, put Jesus up there. And if you’re not Christian, put Krishna or Jade Queen or Uma or Gwyneth up there,” he laughs.

Today’s theme is the immediacy of death, a topic that could easily be intimidating, given a glance at the man in charge. Thurman has a prosthetic eye that stays open when he meditates┬Śhe lost it in a freak accident with a tire iron while changing a flat at age 19┬Śand at six foot three, he bears a slight resemblance to John Wayne. But instead of being scary, he’s reassuring, the type of guy who’s prone to smart, goofy humor and all-encompassing bear hugs. I drift off into bliss until I’m brought back by the voice of Bob.

“We are going to die!” he booms. “We won’t see anything. Our eyes won’t work, our ears won’t work, we won’t smell anything, we won’t taste anything, and we can’t touch anything. So put aside the denial┬Śthis ma├▒ana, ma├▒ana, ma├▒ana feeling┬Śand face the fact that you will die!“

Buzzkill. But this is the dharma, the nature of reality. Since I can’t do much to alter the arrival of my own death, I readjust my lotus position, breathe deeply, and listen.

“When I think about dying, I first get all paranoid and scaredy-cat,” Thurman continues. “But actually it gives me freedom. True freedom. Soul freedom. Spiritual freedom. Inner freedom. Ultimate freedom! Nirvanic freedom! Freedom that is indivisible from bliss!”

Just when I get close to nirvanic freedom myself, meditation time is up. Tranovich steps outside to resume her conversation with her golf buddy, someone complains about the chill, and a boy-monk in a saffron robe shyly asks me for a stick of gum. I don’t have one, so I give him my pen and start heading back down the mountain. On the way, I’m struck by the zoolike sensation of this spiritual mission. But I can’t tell who the real captives are: us foreigners, trying to glean happiness and inner peace in an alien place, or the Bhutanese, who are trying to preserve their ancient way of life while simultaneously stepping into the present.

BY DAY NINE OF NEAR-TOTAL togetherness, I’m worn out by a few of my compadres’ complaints over the lack of electrical outlets for their blow dryers, the insufficient speed of their hotel Internet connections, and the monotony of our buffet lunches, which usually consist of rice topped by ginger beef, cheesy potatoes, and hot chiles.

To cap it off, last night while I was sitting in a restaurant having a glass of wine and asking the guides a few questions, Lily┬Śwho’d just returned from a shopping spree in the village and was wearing new multicolored yak-herder boots to accompany her Cartier dragon pendant┬Śtold me I was acting too inquisitive and instead should just “be.” This was somewhat ironic coming from her; earlier in the afternoon, she’d gone wandering off by herself again, earning one of Olson’s rare reprimands.

“I came here to dance with God!” she told me afterwards. “I didn’t come here to have a chain around my neck!”

Since today’s itinerary includes a relatively straightforward trek to a luxe campsite just beyond the village of Ngalhakhang, I decide to pull a Lily. So I hang back at the trailhead until the last hikers round the farthest bend.

My solitary trek turns out to be the perfect antidote to group-dynamic overload. The Bumthang Valley is thick with forests that eventually give way to jagged peaks, and the mighty Bumthang River roars in my ears like a natural chant. I stop on a footbridge for a while to watch the thunderous swirl and wonder at the way water flows into water. As if to underscore the cosmic abundance around me, I soon discover that the dirt trail is lined with wild marijuana. (Lighting up is forbidden, but some farmers reputedly feed it to their pigs, who fatten up nicely on the weed.)

After two hours of trekking and finding nothing that resembles a village, I’m tracked down by Tshering, one of the locals who’s helping with the trip. Sweating and out of breath, he’s not pleased. “Ma’am,” he scolds me, “you are way off track.”

Chagrined, I follow him up a rutted trail, making stupid gestures and apologizing in English as we walk. He smiles and accepts my apology, but still looks stressed out.

When we finally reconvene with the others at our camp (complete with his-and-hers outdoor showers, roomy tents, and a bar stocked with rum-infused Dragon Warmer cocktails), I expect to be chastised, but instead I’m greeted with the offer of a granola bar and a stick of beef jerky. The generosity heightens my guilt. A true bodhisattva, a person destined to achieve enlightenment, would feel only love and compassion for her fellow psychonauts┬Śnot try to flee from them.

But then I remember what Thurman told me over lunch a few days ago about his own escapist past. A native of Manhattan, Thurman is the son of a stage actress and a journalist, and his first epic quest came in 1958, at age 16, when he ran away from Exeter to join the Cuban revolution. He made it as far as Miami before recruiters for Fidel’s army rejected him because he was too young. Expelled from the tony boarding school, Thurman decided to spend a year in Mexico. Soon after, he was accepted into Harvard and allowed to enter as a sophomore, based on his off-the-charts test scores. Thurman stayed there long enough to become a senior (he would return to the school and graduate six years later), marry a Houston oil heiress, father a child, “behave badly,” and lose his eye. During his post-op anesthesia haze, he decided to head to India.

“I wanted to put my life on the line to find out what I wanted to find out,” he explains.

The heiress promptly filed for divorce, and in 1961 Thurman took a nearly yearlong journey through Europe and the Middle East to India. When he returned, he moved to New Jersey to learn Tibetan and study with a guru, Geshe Wangyal, who, as part of his teachings, traveled back to India with Thurman and introduced his pupil to the then-29-year-old Dalai Lama. “I was 23 when we met,” Thurman recalls. “I thought he was a little juvenile.”

The Dalai Lama was supposed to be monitoring Thurman’s progress. “But I was only the second person he knew who could explain things to him about the West in Tibetan,” Thurman says. “We would have these great gabfests. Then, against the wishes of my guru, he ordained me.”

The monastic life didn’t suit Thurman, however, and a year and a half later, in 1966, he resigned. “I was a failed experiment,” he says. By 1967, he had earned his diploma from Harvard, embarked on his Ph.D., and married a Swedish model named Nena Von Schlebrugge, the ex-wife of LSD pitchman Timothy Leary.

Thurman and the Dalai Lama met on occasion during Thurman’s travels to Asia, but it wasn’t until 1979, when he returned there with Von Schlebrugge and the first two of their four children┬Ś11-year-old Ganden and nine-year-old Uma┬Śthat Thurman felt an overwhelming connection to Tibet’s spiritual leader in exile.

“When I saw him this time,” says Thurman, “I was bowled over by his charisma and spiritual power.” The two have since collaborated on projects like Tibet House, the cause c├ęl├Ębre of glitterati like Christy Turlington, David Bowie, Iman, and, of course, Uma.

Anyone who’s seen the younger Thurman’s hit portrayal of an avenging samurai badass might think her interest in Buddhism is a little contradictory. But Tenzin Bob disagrees. “My take on Kill Bill?” he says. “I hated the violence, but Uma is like a subliminal Kali icon,” a symbol of the Hindu goddess of destruction. “That’s why she’s so popular in Asia.”

THE STAR IN TRIMPHU a few days later is Thurman himself, who’s slated to meet with students and dignitaries for a discussion about gross national happiness, followed by dinner with Bhutan’s best and brightest. The whole entourage is invited. But first we head downtown to support the economy.

A mountain-wrapped city of 55,000 along the banks of a river, Thimphu is the only national capital on earth without a traffic light. The buildings, trimmed with latticework, give off a Swiss vibe, and the shops have suspiciously Western names, like the Buzz Club and U.S. Enterprises. There’s no shortage of Internet caf├ęs, either.

“Thimphu is looking grotty,” Brent Olson says, as we pass gangs of dogs and a crew of workers manually raising a streetlamp.

He has a point: After the stillness of the countryside, the cacophony of dogs barking, horns honking,

The only souvenir I want is a hand-sculpted clay Buddha from the local crafts school we just toured. But they aren’t for sale. And then it hits me┬Śfor two weeks I’ve been surrounded by paintings, statues, and drawings of divine beings, from mustached Guru Rinpoches to Milarepas (a skinny saint from Tibet) and every other possible manifestation of enlightened ones. Their visages appear in temples, on truck dashboards, and carved into rock faces in so many incarnations that I’ve started taking them for granted┬Śjust as I’ve started taking the companionship of my fellow psychonauts for granted.

And now, after meditating jointly on death and selflessness┬Śand after sharing the last 42 meals together, eating things like wild boar and topping it off with an excess of Dragon Warmers┬Śwe’ll disperse to all corners of the globe. Some of us will have found serenity, others will keep trying to muscle their way to it, and some just won’t get it. I’m wavering in the middle, but at least tenet 18 in “The Way of Purification” from The Teaching of Buddha has become crystal clear to me: It is hard to attain a peaceful mind. Or, as it occurred to me at the confluence of the Paro and Thimphu rivers, I can either drive myself mad trying to distinguish where one river begins and the other ends, or I can let myself be mesmerized by the raucous crash they make as they flow downstream as one.

At the festivities a few hours later, Thurman is in exquisite form. He works the crowd like a Buddhist Seinfeld (“Nirvana is that which one seeks through orgasm and death!”) and then launches into a heartfelt plea for Buddhist education. Teaching traditional spiritual values, he says, is the best way to maintain the country’s identity at its most crucial turning point, when it could go the way of isolationism and risk poverty and despair or go the way of globalization and risk being consumed by the beast of Western values.

At dinner, I sit near Chencho Dorji, Bhutan’s only practicing psychiatrist; his clientele’s number-one disorder is anxiety, a result, he says, of fast-paced lifestyle changes. Across the table is Tshewang Dendup, the scruffily handsome actor who starred in the 2003 movie Travelers and Magicians, the first feature film shot entirely in Bhutan. Ironically, he plays the character who is desperately trying to leave Bhutan and get to America, the land of his dreams.

It seems that even Buddhists, the masters of finding nirvana in the here and now, can’t always overcome the urge to search elsewhere. But when I ask Dendup, who is currently making his living as a cameraman for Bhutan’s sole television station, why he’s not heading to Hollywood, he laughs, then sets me straight. “Why would anyone want to go there?”

Freewheeling travelers accustomed to exploring every inch of a foreign land might have a hard time accepting Bhutan’s stiff regulations┬Śnamely the $200-per-day tariff, the required accompaniment by a certified guide, and the fact that some wilderness areas and sacred temples are off-limits. But the restrictions are the very reason the Himalayan kingdom still has so much to offer. And even if busting loose is verboten, creative new itineraries are cropping up all over. Here are some of the best Bhutan tours out there.

Geographic Expeditions offers a wide array of options┬Śfrom meditating with famed Buddhist scholar Robert Thurman to hiking with Bart Jordans, the Dutch author of the 2005 book Bhutan: A Trekker’s Guide (Cicerone Press, $25), the kingdom’s first handbook for hoofing it. The next Thurman adventure is a 14-day trip in November ($6,395); Jordans guides a 36-day trip starting in September ($7,995). 888-777-8183,

Needmore ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°, a rafting-and-kayaking company based in Bryson City, North Carolina, gets you off the beaten path and into whitewater with Exploration of Western Bhutan, a 13-day kayaking-and-trekking odyssey that starts on the rivers of the Punakha Valley and ends at the border of India. On the 13-day Rivers, Mountains, and Dzongs (fortresses) trip, you’ll explore eight different Class III and IV runs, ranging from high-alpine creeks to big-water cascades. $4,400 each; 888-900-9091,

Backroads’ multisport biking-and-walking tour offers marquee cultural attractions, with cardio to boot. You’ll start off the nine-day journey at the chic Uma Paro hotel, in Paro, then loop through Thimphu and the Punakha Valley, home to the massive 360-year-old Punakha Dzong. $4,298; 800-462-2848,

║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°s Abroad lets you compare the idyllic mountains and dense forests of Bhutan with the vast starkness of the Tibetan Plateau and the lush grandeur of the Indian state of Sikkim on a 26-day tour of all three mystical lands. $4,970; 800-665-3998, ┬ŚS. P.

Instant Karma

Bhutan isn’t South Asia’s only magnet for spiritual seekers. For thousands of years, travelers have sought enlightenment in the region’s sacred and spectacular places, from the mountains of Tibet to the plains of India. These five destinations top the bliss list.

Kailas, Tibet This 22,028-foot mountain isn’t for climbing; it’s for circumambulating. Completing the three-day, 33-mile trek around the peak, which Buddhists and Hindus consider to be the sacred hub of the universe, is said to cleanse a lifetime of sin. Circle it 107 more times (that’s 3,500 miles) and obtain complete nirvana.

Swayambhunath Stupa, Kathmandu, Nepal A white dome and golden tower adorned with enormous unblinking eyes greet those who ascend the 365 steps to this hilltop temple. According to Buddhist legend, a shining lotus flower created the pyramid-shaped hill, a pilgrimage destination for more than 1,500 years.

Ganges River, Haridwar, India In the Himalayan foothills where the Ganges flows onto the fertile plains, the city of Haridwar each year attracts millions of pilgrims who come to meditate and soak at five sacred points along the banks of the river, which is associated with the Hindu gods Vishnu and Shiva.

Sri Pada (Adam’s Peak), Ratnapura, Sri Lanka Four faiths claim the oversize footprint pressed into solid rock on this 7,360-foot peak in south-central Sri Lanka, reachable by a four-mile-long ancient stone staircase. Muslims declare the foot was Adam’s; Christians credit Adam or Saint Thomas; Hindus advocate Shiva; and Buddhists say the great Buddha left the impression in a leap from the mountaintop.

Dharamsala, India The Tibetan government in exile resides in this mile-high city, nicknamed “Little Lhasa,” in the breathtaking Himalayan foothills of northern India. When he’s in residence, the Dalai Lama gives public audiences inside the ornate Tsuglagkhang temple; other sacred sites in the nearby Kangra Valley and Dhauladhar Range include the freshwater springs at the Hindu shrine of Bhagsunath and the rock temples of Kunal Pathri. ┬ŚJason Stevenson