Mumbai: The city’s cattle class train commute has put a big question mark over the future of a brilliant sixteen-year-old girl. Raushan Jawwad, who scored over 92 percent in her class X examination a few months ago, lost both legs after being pushed out of a crowded local train near Andheri on Tuesday.

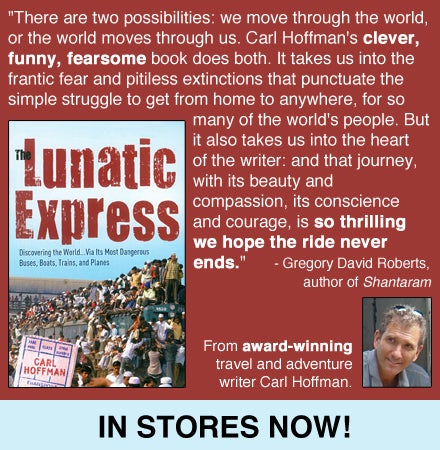

The Lunatic Express

To learn more about the world’s most dangerous buses, boats, trains, and planes, buy and check out .The Lunatic Express

Buy

Buy The Lunatic Express

Buy

Buy The Lunatic Express

buy

buy The Lunatic Express

Buy

Buy The Lunatic Express

Buy

Buy The Lunatic Express

Buy

Buy Times of India, October 17, 2008

“Everything in that book is true,” said Nasirbhai. It was almost 100 degrees, the humidity of the Arabian Sea pressing down, and he was wearing a white dress shirt over a sleeveless undershirt, pleated black slacks, and black oxford shoes. Small scars were etched around brown eyes that studied me from a wide, inscrutable face; a big stone of lapis studded one finger, and a silver bracelet dangled from his wrist. He had a barrel chest and his hands hung at his sides, ready, waitingnever in his pockets. He looked immovable, like a pitbull, like a character from another time and place, and in a way he was. “That book” was Shantaram, the international best-selling novel written by Australian Gregory David Roberts, who’d escaped from prison in Oz and found his way to Bombay two decades ago, where he’d become deeply involved with its criminal gangs and Nasirwho always carried the honorific bhai, “brother.”

“We met in the 1980s,” Nasirbhai said, standing on a corner in Colaba,

By population, the cityjust nineteen miles across, with 19 million soulswas bigger than 173 countries. The population density of America was thirty-one people per square kilometer; Singapore 2,535 and Bombay island 17,550; some neighborhoods had nearly one million people per square kilometer. A neverending stream of Indians was migrating to Mumbai, which was swelling, groaning, barely able to keep pace. In 1990 an average of 3,408 people were packing a nine-car train; ten years later that number had grown to more than 4,500. Seven million people a day rode the trains, fourteen times the whole population of Washington, D.C. But it was the death rate that shocked the most; Nasirbhai was no exaggerating alarmist. In April 2008 Mumbai’s Central and Western railway released the official numbers: 20,706 Mumbaikers killed on the trains in the last five years. They were the most dangerous conveyances on earth.

As we threaded through packed sidewalks and streets toward Chhatrapati Terminus, still mostly known by its old British name, Victoria Terminus (or VT for short), Nasirbhai talked about his life and meeting Roberts. “I was a big man then,” he said. “Fighting every day. Drugs were my business. I sold hash and brown sugar.” Usually when he sold drugs to foreigners, Nasirbhai did the deal and the transaction was over; dealer and buyer went their separate ways. For some reason, however, he and Roberts toked together. “I don’t know why. Destiny. I loved him. And then he started doing brown sugar and I hated him.” The rich smell of garbage and shit filled the heavy air, and Nasirbhai guided me like a child, between lines of traffic and careening buses. “If you’re not like me you cannot live in this city. You have to be tough.” Roberts, like so many foreigners, eventually disappeared, and Nasirbhai didn’t hear from him for fifteen years. He continued to live off the streets and deal drugs. Then, in 2000, he was arrested. Set up. “I sold a lot of drugs to Bollywood starsI grew up with them, with superstars, including Fardeen Khan,” the son of the late legendary director Feroze Khan. For his deals, Nasirbhai used a taxi driver he trusted. The driver had been arrested for selling heroin a few days before, and, under pressure, had agreed to cooperate with police. By the time Nasirbhai met Fardeen on May 4, 2001, police from the Narcotics Control Board were waiting. “We were just making the deal”Nasirbhai had nine grams of cocaine”when a car came up in front and another in back. They jumped out with guns. Fardeen hit the locks, said, What do we do?’ I said, nothing, there is nothing we can do. They have guns.'”

The Bollywood star was released from prison in six days. “His father got him out,” said Nasirbhai, who spent eleven months in Mumbai’s notorious Arthur Road Prison. A few years later, Roberts suddenly reappeared out of nowhere. A ghost, returned. And he wasn’t running from the law anymore, smoking dope and shooting heroin in his veins. He was free, rich, and famous. “It was my destiny; I do not know what I did to deserve this. He told me to stop selling drugs and to reinvent myself. He paid for my house, my daughter’s wedding, my kids’ school, and now he pays me to work for him, only him. He is a man of his word and he saved me. First he became my friend. Then my brother. Then my boss and Godfather.”

VT was like a huge funnel, sucking and channeling the hordes inside; sixteen ticket windows lined the walls, each with a line snaking fifty feet; all of India was here, lying on the floors, walking, running, selling, buying. The line moved quickly.

Nasirbhai barked a few words and out spit two tickets for fifteen rupees eachabout twenty-five cents. We threaded and bounced through the jostling crowds, passed through a bank of inactive metal detectors into the vast departure hall, a vaulted, corrugated roof on cast iron pillars. Built by the British Raj between 1878 and 1888, it echoed Victoria Station in London. “I will show you my style of traveling,” Nasirbhai said. “But first, chai.” It was a constant ritual. Over the next three days, on seemingly every corner, every train station, Nasirbhai and I paused for the sweet milky tea, served in thin, hand-formed clay cups vigorously thrown to the ground or smashed into a bucket when we were done.

“Listen,” he said, as we sipped our tea and a tide of people swept past, “It is very difficult to get inside a train, and once you get in it is more difficult to get out. Sometimes you have to get out three or four stations ahead because you won’t have a chance later.” Many Mumbaikers had commutes of two and three hours each way in and out of the suburbs. A long time to stand up, many had taken to riding the train the wrong way first, to the beginning of the line, where they might get seats. “But sometimes the train changes its route! They get stuck on the wrong train and have to start all over again! And sometimes you get so dirty from the train you feel ashamed. Sometimes it’s so crowded you have to hang outside and there is a very small place between the train and the poles and you hit the poles and you’re fucked. But what can you do? You must reach your job, man. It is fucking terrible.”

We finished our tea, threw the cups on the ground, and strode down the

I didn’t; one of my cardinal rules of traveling was never to carry anything in my back pockets, and I kept my cash divided between the two front pockets, my passport and credit cards and most of my cash strapped to my leg.

“Be careful. You stay close to me. They will look you in your eyes. I meet them and say, Fuck you, man.’ Do what I do, okay?” Sometimes, he explained, when it got really crowded he jumped in the cars reserved for handicapped riders. “And even that is crowded, jammed. People say, You look good, man. Show me your [handicapped] card.’ I say, You show me yours first.’ Fights happen, man. People get killed for their seats.” From his years on the streets Nasirbhai saw the world offensively, a place full of opportunists and thieves and danger lurking around every corner. He was a boxer on the ropes, his guard up every minute. The crowd was a current piling up on the platform like at the wall of a damsaffron and crimson saris and men in blue jeans, and beggars shuffling on their knuckles. “With this crowd, the pickpockets come,” Nasirbhai said. “They work the crowd. But listen, they don’t have magic! They cannot stand far away and make your wallet or phone come to them. They must touch you. So never let anyone touch you anywhere in the world. The beggars are trained. Hello, hello,’ they’ll say, and they’ll feel your pockets. They’ll bump you once. You don’t do anything. They’ll bump you again, and you don’t do anythingyou think it’s an accident. But they’re watching your reaction; the third time they’ll take your wallet or your phone.” In the crowds, hanging on the straps, he warned, opportunists might try to block me with their elbows. But they’d never get Nasirbhai. “My eyes and my brains are how I make money. I can tell: he’s a pimp; he’s a robber. I have that judgment.”

We pushed to the edge of the platform, the crowd building. Waiting. Anticipating. A train came. The crowd shifted; it was one entity. We shuffled to the left, we shuffled to the right. Where would the doorway stop? And before it did, sudden chaoslike the hike of a football on the line of scrimmage. One organism full of individual parts, we scrambled and pushed. The faces were hungry, desperate, and I grabbed the door’s rail and pulled myself onto the train. “And it’s early, man!” said Nasirbhai, laughing, when we squished in. “Come, follow me.” The vestibules were wide and big, but I followed Nasirbhai, squeezing past hot bodies, into the corridor between seats. The trains were industrial, no attempt made for comfort: metal floors, metal walls, metal benches facing each other in groups of two, bars on the windows, hundreds of handles hanging from the ceiling. Nasirbhai pushed me between the windows. It was his spot; there, standing with my ass in one person’s face and my crotch in another’s, my side to the wall, no one could pickpocket me, and fresh air streamed in through the window. Nasirbhai looked triumphant.

The train rocketed through Mumbai, north toward the suburbs. It stopped every few minutes and a mad rush ensued at the doorways. A stream of beggars moved through, including an exotic, sharp-featured woman with skin like mahogany and long black braids woven with marigolds and a red bindi the size of a quarter on her forehead. She wore a tight gold sari and a gold ring in her nose. Nasirbhai gave her a coin and I followed. She blessed us, touching our foreheads. There was something strange and beautiful about her. “A man,” said Nasirbhai.

A man and little girl squeezed through and came to rest, standing, at the end of the bench. Nasirbhai touched the shoulder of the man seated on the end. He ignored Nasirbhai, who tapped again, harder, motioned with his hand to move. Nasirbhai had the look; you didn’t mess with him. The man moved, the woman next to him moved, the whole organism squished more closely together to produce another six inches for the girl to sit.

Nearing Dadar station, we began working our way back toward the

We moved to another platform over a bridge and steps that were shoulder-to-shoulder with people. Sometimes, Nasirbhai said, men just walked up and down the stairs in the crush feeling women. “They go up and down ten times. I don’t understand it, but women, they get fucked. In India, if there weren’t red-light districts, women would not survive.”

We boarded again, this time staying near the open door. DO NOT LEAN OUT OF RUNNING TRAIN AS IT IS DANGEROUS AND CAN BE FATAL, read a sign. Which was like telling the ocean not to leak into a wooden ship. I leaned out, feeling a constant pressure on my back, a wall pushing against me that required resisting at all times. Electrical poles whipped by just six inches away. We cut through slums and past crumbling buildings, black with mold and dripping open pipes, makeshift tents of plastic tarp and string and old tires a foot from the train whipping by. Men and women dozed on charpoyswooden bedsand cooked over open braziers two feet away.

At Thane station I noticed two battered and dented aluminum stretchers leaning against the wall outside the stationmaster’s office. “We have an average of ten deaths a month within seven kilometers of this station,” said Miland Salke, Kandivali’s deputy stationmaster, below a hand-lettered sign: LIST OF HOSPITALS AND UNITS IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD OF KANDIVALI. He shrugged, waggled his head. Today, he said without emotion or amazement, there had been three accidents. Just outside of the station a man had walked up to the tracks and then, at the right moment, laid his head down on the hot steel. He died instantly. A suicide. At 1:00 a.m., nine hours before, the last Western Line train of the night slid into Kandivali Station and cut a fifty-five-year-old man into two pieces. He was trying to cross the tracks. And a few hours later, as another Central Line train pulled into Thane, the crowd ejected a young man out the door. I could feel it, had just felt it as we’d pulled into the station like a watermelon seed squeezed between your fingers. He, too, died instantly.

It was now rush hour, and after another round of chai we prepared for battle. Passengers ten deep waited on the platform stretched out over 100 yards, the womena riot of swirling purples and blues and golds, of black braids and golden bracelets and bangles and nose ringsin their own group, angling for the “ladies'” cars. A train camethey came in fast. It was full, packed, not an inch to spare. The crowd became one again. A thing. It moved forward. Left. Right. Slowly at first; you couldn’t know, after all, where the open doorways would pause. Then, suddenly, an explosion, a riot, a volcanic eruption, a struggle balancing on the edge of life and death.

The train was slowing. People burst from the doorways and leapt into a crowd that was surging forward toward the very same door. The struggle was short and violent; you pushed, were pushed. Your body feels a crushing weight, a powerful wave at your back. You cannot stop or even pause. But your feet cannot move fast enough. You shuffle your feet forward, try to keep them under you. Your only hope is to grasp the door, a pole, a handle. Anything. There is punching. Elbows sharp in my kidneys. I see a man palm another man in the face. I am nearly at the doorway. The man in front of me fallshis body is being pushed, but his feet can’t move fast enoughthey get stuck at the step up onto the train. Another man falls onto his backthis is how people are trampled to deathand I am next. I grab the edge of the door to steady myself, to resist the surging weight and wall at my back, to pull into a place where there is no room. The men will be crushed. The crowd is a spasming muscle. One of the downed men shouts. Somehow, hands reach down and pull them up. A shoe is left behind; it will never be recovered. And then we’re in. Tight, from hips to shoulders. I cannot move, but I must. To stay in the doorway is to risk death at the next station when the next violent pulse comes. “In ten years,” Nasirbhai said, “you will need helmets and football pads just to travel to work!”

It was now dark, after 8:00 p.m., and I felt exhausted. “Come,”

We emerged from the rickshaw at a concrete apartment building, and I followed Nasirbhai down an alley of rubble, the building completely dark, without electricity. We wound through narrow concrete halls and up concrete stairways, and came to a one-room apartment full of shadows and dancing candlelight. There was one chair, a television, a mattress pushed up against the wall, and a poster of Mecca, and three men sat cross-legged on the floor. One of them was old, with a single tooth, wearing a skullcap, and was called Nimagrandfather, said Nasirbhaiintroducing me to his son-in-law’s father and his sons. As they talked in Hindi, someone brought out a chilluma hash pipeand a ball of moist Kashmiri hash, which Nasirbhai rolled and mixed with tobacco in the palm of his hand, back and forth, back and forth, and packed it into the pipe. “I don’t drink or smoke anymore, since my mother died. It makes me bad; I want to fight.” He took a square of white muslin, wet it, squeezed it, and wet it again and squeezed it tight and wrapped it around the mouthpiece and we smoked, except for Nasirbhai, the pipe passing around, as a little girl wandered inthe old man’s great-granddaughterand plunked down in his lap and two generations of the family got stoned together, and the hash was good and sweet and the talk and language rolled and I wondered where I was and how exactly I’d gotten here and the world seemed so varied and rich and beyond my comprehension. We smoked a couple more bowls, the pipe passing round and round, and by the time Nasirbhai and I were back on the train heading downtown, it was nearly empty, just a big steel tube clacking and rattling, the wind hot and smoky at the door, fires burning on the tracks illuminating the dim shadows of hundreds ofpeople walking and squatting in the night.

Nasirbhai knocked on my door at six-thirty the next morning in order to hit the morning rush hour. “Come,” he said. “I have been up since five and we must have breakfast and tea.” We entered a café full of round wooden-legged tables topped with thick marble slabs, the walls covered with mirrors, the waiters all in dhotis and caps, with beards. “This place is very old,” Nasirbhai said as we sipped tea. “It’s been here since I was a boy and it is just the same.”

We spent the morning fighting the crowds on the Churchgate line and, near noon, Nasirbhai took me to St. George’s hospital, around the corner from Victoria Terminus. “Let’s find some bodies,” he said, “some victims of the trains, and you can see for yourself.” That seemed weird and impossible, but he insisted, said he had a friend at the hospital who’d help. The hospital was a huge block of stone, built by the Raj in 1908, with arched windows open to the dust and heat. We stood in an open hallhushedas ceiling fans beat the humid air and the twittering of birds wafted in. A man sat in a wheelchair, his head swathed in bandages like a character in a movie; another man lay on a stretcher. Nasirbhai talked to people, stalked the halls and said his friend wasn’t herehe had been injured on the train! It seemed a joke, but Nasirbhai didn’t acknowledge the irony. “But don’t worry,” he said. “I am known and people will see me and come.” Which people did, approaching him and whispering in his ear, until Nasirbhai barked “Come!” and took off out the front door. We padded down the steps, walked around the hospital and down a cobblestone alley that turned into a crowded row of shacks and houses running alongside the hospital. Big black crows hopped and cawed; mangy dogs covered in scars, with drooping teats, lolled in the sun. Smoke. The reek of garbage. Geese and roosters pecked at the heaps of trash. We came to an eight-foot-high concrete wall, mottled black with mold and soot. A steel gate, crooked on one hinge, lay open. The flag- stone courtyard of a small concrete building with a corrugated roof piled with broken chairs, the limbs of bare trees, a couple of rubber tires. Those big black crows everywhere. Watching. Waiting. Cawing. This was the hospital’s mortuary.

Two men were sitting on a wooden bench. Nasirbhai strode up to them and spoke in rapid Hindi. “Sit down, Carl,” he said, introducing me to Santosh R. Siddu and his son, Sanjay. Santosh, fifty-five, had a long brown face and a prominent, almost Roman nose, a thin mustache. He wore unhemmed

I followed Santosh inside: the room was twenty feet square, unpainted concrete, black with age and mold. Two marble tables stood in the middle; haphazardly spread across one of them, and on shelves in a corner, were plastic jars. “Spleen,” Santosh said, pointing to one that looked like a sponge soaked in blood. “Intestines. Heart. All of these are filled with body parts.” A white enamel tray held a stainless-steel hammer and chisel, a pair of scissors. They had dark stains, bits of something. I had a feeling of dread; it felt hot and cold at the same time. “We have a minimum of two or three bodies every day from the trains,” Santosh said. “Maybe seventy-five percent are unknown, and sometimes the bodies are so destroyed we can’t tell much. Sometimes suicide, sometimes they’re drunk, sometimes they are old and get jarred so much in the crowd they have a heart attack.” A goose honked and poked its head into the room. Deathraw, banal deathhung in the air. So much ceremony surrounded death, gave it meaning, raised it to sadness and glory, and nowhere was that truer than in India. Except this felt like I was seeing the man behind the curtain. One minute you were riding a train to work or to hang out with your family, the next you were cut up on a marble slab in a hot, dirty concrete room. Dead. No glory. No future. A piece of meat. Santosh poked around in a corner piled with papers and pulled out a log book. “Today Balkishan Kakoram. Forty-seven years old. Hindu. He was traveling and fell. He is railway postmortem number 290.” That was, the 290th victim within eight to ten kilometers of the hospital this year. He had died an hour and a half before our visit. “The station sweepers take the body and the railway police bring it here.” In the last twenty-four hours there had been four deaths. One had lost his arm, two their heads.

Santosh led me out of the room, to a tiny antechamber with a corroded steel door with a refrigerator-like handle. He pulled it open. The smell of death made me gag. I almost vomited. A dark room. Bodies lay on shelves. A crumpled, bent, contorted figure lay in a pool of liquid on the floor. Meat. Human meat caught in the mad wheels of the daily grind. A commute that chewed you up and spit you out, so mammoth an assembly line of human movement going so fast that not everyone could keep up.

The crows cawed. Santosh shrugged. “One of them, a man, his whole right side is gone; his liver is gone.”

A call came; a doctor was heading over from the hospital to watch Santosh perform the postmortem on Balkishan Kakoram. He threw on a plastic apron and some rubber gloves and we went outside. He finished quickly. Fifteen minutes later he came out and we squatted in the alley and drank tea, and father and son smoked another bowl of hash. Three small boys played a game of cricket with a chipped bat against the mortuary wall. “He went for his job and didn’t reach his office. The train came into VT station at nine-thirty this morning and he jumped off but he jumped the wrong way and his ankle got caught and he broke it and fell and hit his head.” Father and son were close; they leaned on each other, bumped bodies, held hands, draped their arms around each other. And they lived next door to the gruesome place. “He fell hard; his brain was full of blood.” Sanjay was twenty-five and would take over from his father, who’d been conducting this grim business for twenty-eight years. “I can do ten a day,” Sanjay said, taking a long draw off the pipe. “But some bodies come in decomposed and there are many maggots and gangrene and my father has to do it. I can’t. The bodies smell so bad I faint.”

Another round of the pipe; Nasirbhai knew his stuff, knew how to make people talk. “But it is hard, you can’t bear it,” said Santosh. “Any normal person would faint within minutes.”

“We drink together,” said Sanjay.

“I must eat after a postmortem,” said Santosh. “Meat. Lots of meat and drink!”

They jostled each other, laughed loudly. But it was a mask. “Without drink,” said Santosh, “you cannot do this job.”

“When I travel on the train,” Sanjay said, taking a long hit off the pipe, “I am very cautious.”

IT WAS TIME for me to leave Mumbai; I wanted more crowds and decided I’d push on to Bangladesh via a train to Kolkata. Nasirbhai said he’d get my ticket, and late that afternoon I hopped on the back of his motorcycle and we ripped through the streets of Colaba. Every streetcorner had groups of men and boys lounging, sitting on cars and motorcycles and curbs, and Nasirbhai roared from corner to corner, pausing, talking, introducing me. There was an army here, just sitting and waiting and watching, and soon Nasirbhai had them getting me a ticket. I paid in advance, and he said my ticket would appear at my hotel that evening. “Don’t worry,” Nasirbhai said. “You will get your ticket. They wouldn’t dare not come through.”

Which they did, and at five the next morning I threaded past rows of

Someone shook my shoulder. I woke with a start, lost for a minute, unsure of where I was. The conductor, in a black blazer and white pants. “Ticket,” he said. I handed it to him. He studied it. “Your ticket is not right!” He pointed to the man who’d had the violent outburst. “I will reaffirm and return,” he said, marching off. Fifteen minutes later he came back. “Your ticket is affirmed,” he said, “but it is not for here. You must move.”

I pulled my bags from under the bench. People stared, as I squeezed and bumped through crowded aisles down six cars.

“Are you Washington?” said a man with a gray mustache, glasses, and gray pinstriped slacks, his bare feet wiggling in the air.

My ticket said where I lived instead of my name. “You are late, but you are welcome!” I squeezed in. Directly across from me sat a young couple, she in gauzy saffron sari and shawl that covered her hair, with a gold nose ring; he with a small beard and thick, heavy lips. They eyed me suspiciously, four brown eyes burrowing into me. The train rattled and shook, the noise roaring, wind pouring in, sometimes thick with the smoke of burning trash and burning fields. Goats munched on stubble. Cotton fields and bullock carts, a now blue sky, the endless fields and villages of mud brick of the motherland passing by hour after hour. A stream of beggars slid, skidded, and shuffled by. A man with no legs. A boy with no toes, his foot just a formless round ball. A man with no eyes in a soiled dhoti, led by a withered-looking woman singing a haunting melody. When the man with the mustache gave a coin, so did I. Chai sellers. Sellers of newspapers and magazines. I quickly became covered in dust and grime. At noon a man in a uniform came by and rattled away in fast Hindi. “Do you want lunch,” asked Mustache.

“Yes,” I said.

He returned a few minutes later with paper plates of dal and naan and a vegetable curry, but there wasn’t enough to go around. Mustache insisted I take his. I tried to refuse, but he wouldn’t hear of it. I tucked into Raymond Chandler’s Farewell, My Lovely, even though reading on trains or buses often felt unnerving. Books sweep you up, take you away, transport you. I read Philip Marlowe’s gritty tromp through 1930s Los Angeles and stopped and looked up and felt totally lost. I wasn’t in 1930s Los Angeles or my living room or on my front porch. I was on a train hurtling through India. Suddenly I felt the dirt and heat and wind, and an utter aloneness, strangers crowded against me. It was one thing to be in it constantly, to be focused and present, another to forget it and myself for a few minutes, and then to be suddenly conscious of where I actually wasthe puddles on the bathroom floor, so many eyes staring at me, all alone rattling through India. Which sent me into overwhelming feelings of alienation and disconnect, feelings that had been slowly growing with every mile, especially since Indonesia. Desperate to talk to someone, to touch, to feel love and human warmththat was the flipside of my wandering. No matter whom I talked to in my travels, whether it was Moussa on the train in Mali or Fechnor in Mombasa or Daud on the Siguntang, I couldn’t kid myself. They were fleeting connections, shallow and temporary and no substitute for the real thing. As the steel train clacked and shook and rattled and a man with a leg twisted at some impossible angle hobbled by on wooden crutches, I wondered what I was doing there. For the first time I wondered if I’d been fleeing from human connection itself. If that’s why I felt happy on muddy dirt roads in the farthest Amazonnot the escape from bills and deadlines, the mundane details of everyday lifebut from the emotional tentacles of human intimacy. Out here I could miss my family, my crazy parents and my friends. I could fantasize that I was a whole person who was just away for a job. There must be a reason, I had to admit, that I couldn’t stay home, that I always sought another adventure, that the idea of spending five months away from home on the world’s worst conveyances felt so good,that escape was so much part of my life. It was a stark realization. It hit me hard. It crashed down on me, swallowed me up. I scribbled in my notepad: I wanted to be known, not just for a few days by strangers passing me on conveyances. The truth was, I had a fear that if people really did know me, they’d flee, and I hadn’t felt known or understood by anybody for a long time because I’d hidden myself from them, kept them away. I looked around. Poor old Fechnor in Africa, still sad over the charcoal seller with trading in her blood; he and I, we were both hiding in places where no one could ever really know us.

By nine that night I was rattled. I had been sitting bolt up- right on a hard bench by the open window for fifteen hours. Every muscle and bone in my body ached. I was hungry. The woman across from me winced, rubbed her stomach in distress, picked her nose. Her husband spat out the window, a tiny drop hitting my face, showed her his gums. And I was cold now and covered with a layer of black dust, my hair stiff and gritty.

I thought of Santoso holding my hand on Buru and how good that had felt. Maybe it was all starker in places like India and Indonesia or Africa, where family was everything, where there was no personal space, where there was no being alone, where everyone felt deeply connected to their home. Could I reconnect?

Couples rarely publicly embraced in India; there was no such thing as a public kiss even in Bollywood. But the staring couple across from me sat close; her head lolled on his shoulder as she fell asleep to the shaking train and the heat.

Mustache peeled an orange, broke it in two, and handed me half.