Escape the monkey house and take your brood to where the wild things really are. Our kid-endorsed guide to sneezing lizards, daffy otters, and bellowing moose. (Sorry, no dinosaurs.)

Koalas in Kangaroo Island

Though the koala is right up there in the race for spokescreature for Australia (second only, it seems, to aging squintmeister Paul Hogan), there are few places on the continent where you can actually see it in the wild, since much of its natural habitat has been wiped out by development. But on little- populated Kangaroo Island (a 30-minute flight from the South Australia city of Adelaide) koalas are everywhere. That’s the good news for families who dream of seeing the cuddly little marsupials outside of zoos. The bad news is that there are so many on the island that they are devouring the eucalyptus forests they require for survival and are in the process of having their population reduced through vasectomies and relocation to the mainland. Koalas were introduced to the island, Australia’s third-largest, in 1920 at the height of demand for koala pelts; millions were killed throughout Australia before protective legislation was passed in the 1930s. The island’s 18 national parks and conservation areas include the untouched bushland of Flinders Chase National Park, where you’ll spot koalas asleep, limbs dangling, in the fragrant, mildly toxic trees that serve as their homes and constitute their entire diet. Don’t expect to see a whole lot of zany koala antics; their extremely slow metabolism (and the fact that eating only leaves makes them slightly loopy) means they sleep about 19 hours a day. When they do move, usually at sundown, it is to shimmy down one tree and up another in search of an even more perfect branch on which to take a snooze.

WHAT ELSE YOU’LL SEE: Kangaroo Island kangaroos, Tamar wallabies, Australian sea lions, fur seals, brushtail possums.

MIGHT SEE: Short-beaked echidnas, platypuses, southern brown bandicoots, fairy penguins.

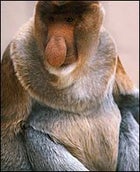

Proboscis Monkeys in Borneo

Why haul your family all the way to the swampy mangrove forests of coastal Borneo to see the proboscis monkey? Because this Western Pacific island southwest of the Philippines is the only place on the planet you’ll find this endearing two-and-a-half-foot-tall oddball primate with its bowling-league potbelly, its lunatic territorial honks, its gravity-dissing leaps from branch to distant branch, and its wondrous, pendulous nose. Male proboscis monkeys have the best schnozzes in the monkey business—droopy, three-inch-plus snouts whose exact purpose is not known. Researchers think the nose may act as a sound amplifier for the monkey’s ritualistic swamp-shaking cries. One thing they have noted in the field: Size does matter. Female proboscis monkeys prefer the males with the largest noses. The monkeys travel in groups of 15 to 20 and live, quite noisily, in trees along Borneo’s riverbanks. Though generally shy, they seem to have gotten used to human presence in certain regions, including Tanjung Puting National Park, on the south coast of the Central Kalimantan province of Indonesian Borneo, and Kinabatangan Wetlands Sanctuary in Malaysian Borneo, on the island’s north coast. Guided monkey-viewing trips are run in riverboats and dugout canoes morning and evening, when the chances are best to view the hyperactive monkeys playing by the water’s edge, swinging from limb to limb, and sometimes leaping out of 60-foot-tall trees into the water below and using their powerful legs to swim across the river. Though Borneo’s “dry season” is March through August, this is the rainforest; you can expect heat, humidity, showers, and, yes, mosquitoes in summer.

WHAT ELSE YOU’LL SEE: Orangutans, gibbons, long-tailed macaques, hornbills, green turtles, hawksbill turtles.

Sea Otters in Alaska

The mile-deep fjords and mist-softened forests of Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula are home to a variety of impressive A-list wildlife: humpback whales, bald eagles, black bears. But we’re betting that the animal your kids will most fall in love with in Alaska—and most envision buckling a collar around—will be the sea otter. Sea otters spend their days trying out new ways to do cute. In the tranquil coves of glacier-fringed Aialik Bay, they gather in large groups, or “rafts,” to roll around, dive, hug, float, and roll around some more, interrupting their fun every now and then to use rocks to crack open mussels on their chests—in the most adorable way possible. Researchers have noted that otters form rafts not for protection from predators or for hunting; they get together to rest and help each other through rough seas.Though you may catch sight of them sleeping on icebergs as you glide past in a sea kayak, sea otters are often best observed from shore. Laying low on a beach, you can watch them cavort and listen to mothers and pups calling to each other across the water. Alaskan sea otters were hunted nearly to extinction in the early 1900s by Russian fur traders for their extraordinarily dense pelts, but their population had recovered to about 150,000 a few years ago, before scientists recorded the disappearance of large populations near the Aleutian Islands. One theory for the decline: orcas may have started turning to sea otters for food because seal and sea lion populations have also been slipping.

WHAT ELSE YOU’LL SEE: Land and river otters, Steller’s sea lions, harbor seals, bald eagles, puffins, auks, pigeon guillemots, cormorants, marbled murrelets.

MIGHT SEE: Black bears, salmon, coyotes, humpbacks, and orcas.

Sperm Whales in Norway

Moby Dick, an “intelligent malignity.” But the whale is malign only if you happen to be a giant squid (the average 45-ton, 55-foot-long male sperm whale will dive down to 4,000 feet hunting squid and can consume about a ton of them a day). Sperm whales live—and have been hunted—in every ocean on the planet. Though their population was decimated by the whaling industry, they now number about 200,000 worldwide thanks to a 1986 ban on sperm whaling. These days their only pursuers in Norway are the fleet of research vessels that make the three- to five-hour round-trip from the small fishing village of Andenes to see some of the several hundred male whales that spend the summer offshore. Though the boat trip on the open sea can be rough and cold, the islands’ climate is generally quite mild in summer. Midday temperatures range from 60 to 70 degrees; temperatures drop down to the forties or fifties in the evening when the sun dips low, but never sets.

WHAT ELSE YOU’LL SEE: Minke whales, killer whales, eagles, gannets, seals, terns, cormorants.

Elephants in Tanzania

Between 300,000 and 600,000 African elephants—roughly half the number that existed just 20 years ago—survive south of the Sahara. Though a ban on ivory helped ease the pressure on the elephant, rampant development continues to be a threat in Africa, where only about 20 percent of elephant habitat is on protected land. It’s possible to encounter pockets of pachyderms on game-viewing trips throughout the continent, but the best place to see large herds in summer is Tanzania’s Tarangire National Park, a sweeping 1,600-square-mile expanse of baobab-dotted grasslands just southeast of Lake Manyara and the Ngorongoro Crater. During the dry season (June to November) as many as 300 elephants at a time join other wildlife crowding the banks of the Tarangire River, the park’s only permanent water source. Watch a herd of elephants for a while and you can’t help but be moved by their power and grace, the tenderness with which they treat their young, and, above all, the astonishing deftness of those funky half-lip, half-nose trunks as they draw water to their mouths, shower, trumpet, strip bark, shake fruit off trees, guide babies, pick up tiny leaves, spray themselves with dust, sniff, dig wells, and high-five (high-one?) each other. Elephants have even been known to swim underwater using their trunks as snorkels. While you probably won’t get to see the snorkel act, you will get quite close to the herd in your safari vehicle. Walking is prohibited in most of Tanzania’s game parks—probably not a bad thing since 13,000-pound elephants can run as fast as 25 miles an hour.

WHAT ELSE YOU’LL SEE: Zebras, wildebeests, buffalo, eland, giraffes, oryx, gazelles, impalas.

MIGHT SEE: Lions, cheetahs, spotted hyenas, rhinos, leopards.

Moose in Wyoming

Moose, the largest members of the deer family, are found all over the Northern Hemisphere, but if you want to see these gawky giants at their most majestic, head for the northwest corner of Wyoming. It’s nearly impossible to appear anything but divine with the 13,000-foot Teton Range as a backdrop. Christian Lake, Willow Flats, Oxbow Bend, Inspiration Point, Antelope Flats—the names of moose hot spots in the Greater Yellowstone region, one of the last nearly intact temperate ecosystems in North America, read like cowboy poetry. Moose are not hard to find: Sometimes it’s as simple as joining an “animal jam,” a traffic snarl created by the sight of a roadside moose. More exciting, though, is an encounter away from pavement, on trails around the marshy fringes of cobalt-blue Colter Lake or in the wetlands along the Snake River where moose browse on willows and wade in shallow ponds to feed on aquatic plants. Remember, though, that moose are huge, powerful, fast—and often cranky. In late spring and summer, cow moose with young calves are very protective and will attack humans who come too close. During the fall mating season, in late September and October, bull moose, which can stand over six feet tall at the shoulder, weigh 1,600 pounds, and sport 50-pound racks of antlers (which can grow one inch per day and are shed yearly), may also be aggressive, especially toward people with cameras around their necks, waving their arms and hollering, “Hey, Bullwinkle!” Moose, after all, value their dignity.

WHAT ELSE YOU’LL SEE: Bison, elk, black bears, grizzly bears, coyotes, pronghorn antelope, trumpeter swans, sandhill cranes, ospreys, marmots, pikas, maybe wolves.

Marine Iguana in the Galápagos

Marine iguanas are big, spiny, sluggish, awful-looking lizards that sneeze a lot. Even critterphile Charles Darwin pronounced them “hideous.” What more could a kid ask for? The only seagoing lizards in the world, they are found exclusively in the volcanic, equator-straddling Gal├ípagos Islands, 600 miles west of Ecuador. Like many of the species in the Edenic Gal├ípagos, marine iguanas are unafraid of humans and will allow you to get as close to them as you wish. (Of course, you could just stay on the boat and have a cocktail while your kids go see the nice lizards.) Though they feed mostly on marine algae in shallow tide pools and exposed reefs, the largest (males grow up to four feet long) can dive as deep as 40 feet and stay underwater for more than an hour. The George Hamiltons of the reptile set, cold-blooded marine iguanas are compulsive sunbathers, using hot lava rocks to elevate their body temperature before and after swimming. At dusk, they heap themselves together in nightmarish pig piles in order to conserve body heat. Excess salt in their diets is removed with frequent sneezing, which explains their particularly fetching feature of having their heads constantly encrusted with salt. Though there are some 200,000 to 300,000 marine iguanas—or about 4,500 per mile of coastline—scattered across the 50-island Gal├ípagos archipelago, on many islands they are losing the survival battle against egg-attacking rats and feral cats.

WHAT ELSE YOU’LL SEE: Blue-footed boobies, giant tortoises, lava lizards, Gal├ípagos penguins, flightless cormorants, flamingos, Sally Lightfoot crabs, Eastern Pacific green sea turtles, Gal├ípagos fur seals, dolphins, waved albatross.

Scarlet Macaws in Costa Rica

Scarlet macaws are just what you dream of in a tropical bird: flashy, big, loud—and easy to spot from the comfort of a palm-shaded beachside hammock. Of the three known existing scarlet macaw population centers in Central America, the best place to see the three-foot-long, red, blue, orange, and yellow parrot is in and around Corcovado National Park, an area of unequaled biological bounty on Costa Rica’s south Pacific coast about 200 miles from the capital San Jos├ę. Corcovado encompasses a wide range of habitats—from dripping, all-but-impenetrable cloudforests to croc-friendly swampland to broad Pacific beaches where jaguars sometimes prowl at night. More than 100 species of mammals, 123 species of butterflies, 367 species of birds, 117 species of reptiles and amphibians, and 40 species of freshwater fish—at last count—make Corcovado their home. But few species are as full of beans and as much fun to watch as the scarlet macaw. You’ll find them easily enough: feeding in almond trees within park boundaries, ripping into ripe figs along the shore around the low-key tourist lodges on the park’s periphery, or flying in pairs or small flocks—at speeds of up to 35 miles per hour. And when you don’t see them, you’ll surely hear them. Macaws keep up a nearly constant stream of raucous, cartoonish cries—even in flight. Their boisterousness and uncamouflaged beauty have made them easy prey for hunters in the pet trade. That, and their ever-shrinking habitat, has landed them on the endangered-species list.

WHAT ELSE YOU’LL SEE: Howler monkeys, spider monkeys, white-lipped peccaries, American crocodiles, caimans, poison dart frogs.

MIGHT SEE: Baird’s tapir, pumas, hammerhead sharks.