THE DRUNKEN soldier in the airstrip waiting room put down the AK-47 he'd been pointing at my head and picked up a pair of bricks. This was progress. Bricks don't go off by themselves; their clips are not emptied out of fear, or habit. Bricks take willpower, aim. Besides, despite demands for beer money and much raving about my motives for being in Saurimo, a backwoods diamond-mining town in the far east of the country, it had become clear that the soldier was not 100 percent serious about killing me. He simply wanted to make a point about his life here, in Angola.

Farm workers watch as fields burn outside Saurimo

Farm workers watch as fields burn outside Saurimo A lone Baobab stands guard on the Angolan coast near Qui├žama Park.

A lone Baobab stands guard on the Angolan coast near Qui├žama Park. “I have lived many lifetimes in this hole”: Chyngandangaly, a diamond mine outside Saurimo.

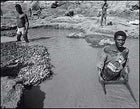

“I have lived many lifetimes in this hole”: Chyngandangaly, a diamond mine outside Saurimo.

A garimpeiro at work.

A garimpeiro at work. Refugees loiter around a supply truck.

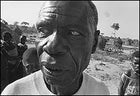

Refugees loiter around a supply truck. The Soba

The Soba Mealtime at an orphanage in Huambo

Mealtime at an orphanage in Huambo “In this sad life”: Pentecostal worshipers dance on the beach south of Luanda after a funeral.

“In this sad life”: Pentecostal worshipers dance on the beach south of Luanda after a funeral. One deportee, set loose in Qui├žama.

One deportee, set loose in Qui├žama.

“Kuito!” the soldier exclaimed, shouting the name of the devastated city on the central Bi├ę highlands, scene of some of the fiercest fighting in the longest civil war in African history. “Kuito!” he repeated, pointing to the swatch of blistered skin on his left forearm. The UNITA rebels had put fire on him in Kuito. “Huambo!” he announced, displaying a six-inch gash on his rail-thin lower thigh. He'd been shot in the leg in Huambo.

“Moxico!” he said. One of the fingers on his right hand was missing. It had been blown off in Moxico (pronounced “mos-SHE-co”), the giant eastern province.

“Moxico, Angola! Kuito, Angola! Huambo, Angola!” the soldier reprised, waving the bricks in the air, as if his body was a wound-by-wound primer of his beleaguered nation's geography.

Then he dropped the bricks. They were nothing but props anyway, and he had something much better. Removing his khaki cap, the soldier rammed his head into my chest.

“Olha ai!” he shouted in Portuguese. Look here!

His head had a hole in it, a dark well descending into his cranium. About a half-inch in diameter, deep enough to store a small marble, the depression was located where one might find the centering whorl on a young boy's scalp.

It couldn't have been a bullet hole. How could he have lived through that? No, he must have gotten hit with a pickax, a rake, the point of a machete. Either that, or someoneÔÇöhis mother? God?ÔÇöhad pressed a thumb into his yet unformed skull.

“Olha!” the soldier yelled once more. But the menace was gone, replaced by plaintive desperation. He couldn't have been more than 20, but he looked incalculably older.

Well, I'd come to see the lingering nightmare, hadn't I? And here it was, presented on a platter, right down in the black hole in this poor dude's noggin. What lurked in there, what bad videos? The legacy of the slave-master Portuguese who during their 500-year reign had shipped roughly four million Angolans off to the plantations of Brazil and Hispaniola? Jump cuts of a thousand malarial nights sleeping in the bush waiting for UNITA's rebel M-16s? Angola was a land full of grievous memories, unhappy ghosts. Perhaps the poor guy had punched that hole in his head himself, in a vain attempt to release the demons.

But now there were other soldiers in the waiting room, a dozen men in camouflage from the For├žas Armadas de Angola (FAA) carrying AK-47s, ready to be shipped out to some new venue of potential doomÔÇöall of them young like him, all looking just as haunted. In Angola, there are always more guys with AK-47s.

Get up, they told their drunken comrade, no more Castle beer, no more shouting at the tourists, time to move on. The soldier grunted, clamped his cap down over his broken head, and picked up his gun once more.

“Olha…Angola,” he said, one more time, and walked out.

╠ř

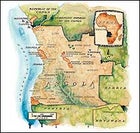

IT IS A FABLE YOU HEAR TOLD all over this country, about how when God made Angola, he was in a very happy mood. Tucking it into the southwest coast of Africa, with Congo to the north, Zambia to the east, and Namibia and Botswana to the south, he gave Angola every manner of gift: vast diamond fields, huge oil deposits, numerous rivers flowing throughout the countryside. He gave it savannas teeming with wildlife and farmland second to none, with wide and rambling meadows for grazing animals.

When the other African nations saw what God had given Angola, they protested. Why did Angola have so much, when we have only this pile of dust, these rivers of disease? God agreed. He'd been too generous to Angola, but there was no changing it now. What was done was done. As recompense, God made the Angolan people so contentious, so disputatious, that they would never be able to enjoy the riches he had given them.

So present-day Angola came to be: a perpetually war-torn (basket) case of extreme underdevelopment, even in a continent known for underdevelopment; a Marxist reverie of contradiction in a land run by former Marxists. The fighting there has spun out in stages, each one a devaluation of moral imperative. What began in 1961 as a heroic war of liberation against Portuguese dictator Alberto Salazar's bankrupt, teetering colonial regime degenerated into a messy, ethnic-based shootout even before independence was gained, in 1975.

The short history: Holden Roberto, leader of the populist National Liberation Front of Angola (the FNLA, primarily composed of Bakongo people from the north), was backed by Zaire and, until he lost, the United States. Agostinho Neto, a Marxist poet turned revolutionary, led the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (the MPLA, largely Portuguese-speaking urban elites from the Mbundu tribe), and was supported by the Soviet Union and 50,000 Cuban troops. The MPLA vanquished the FNLA, but in 1979, when Neto died, he was succeeded by a 37-year-old oil engineer named Jos├ę Eduardo dos Santos, who has retained power ever since, reconfiguring the formerly Marxist MPLA government into a capitalist kleptocracy. Dos Santos was, in turn, opposed by the ruthless, charismatic Jonas Savimbi and his agrarian army of Ovimbundu tribesmenÔÇöthe National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA)ÔÇöwhich received money and arms from the United States and active military support from apartheid-era South Africa.

In the late 1970s and 1980s Angola became a roaring, orgiastic Cold War proving ground. Despite a fitful series of cease-fires and three failed United Nations peacekeeping missions, including a highly disputed 1992 election in which Dos Santos defeated the much-feared Savimbi, the war ebbed and flowed, killing upwards of 500,000 people. Now it appears to have sputtered out, though Angolans are justifiably leery about its closure. When the 67-year-old Savimbi was killed last FebruaryÔÇöreportedly shot 15 times in an ambush led by Angolan army troops in MoxicoÔÇöthe Dos Santos government had to unleash what The New York Times termed a “press offensive” to convince the populace and the world that the long-demonized UNITA chief was really dead. It took several minutes of TV footage showing Savimbi's lifeless bodyÔÇöstill decked out in his olive-drab UNITA fatigues, his pants falling down, a bullet hole in his neckÔÇöto do the trick.

My journey, which took place before Savimbi was killed and his tattered, malnourished UNITA troops straggled in from the bush to sign a cease-fire agreement, was originally conceived as a mission of sorts: to see what the future held for Angola, once so lush and beautiful, as it re-emerged from a quarter-century of ruination. Twenty-seven years of civil war can generate a raft of impressively gruesome statistics. As of 2000, according to the UN Children's Fund (UNICEF) and the World Health Organization, 62 percent of Angolans were without access to safe drinking water, 56 percent lacked adequate sanitation, and 16 percent (2.1 million people) were afflicted with malaria. As much as 30 percent of the population live as deslocados, internally displaced people, in refugee camps run by the government and aided by the UN World Food Program; currently, half a million are starving due to famine. Almost a third of the country's children die before the age of five. More than 54 percent of Angolans are younger than 18, and life expectancy hovers around 36. According to the latest statistics, only 50 percent of school-age children attend classes, and nearly half the population is illiterate.

In 1999, UNICEF declared Angola, of all the ravaged spots on the globe, the single worst country in which to be born.

╠ř

THE WORST PLACE IN THE WORLD you might have the misfortune to be bornÔÇöthis is what most people in Angola refer to as “the situation,” or the ▓§ż▒│┘│▄▓╣│Ž├ú┤ă.

The ▓§ż▒│┘│▄▓╣│Ž├ú┤ă is what passes for everyday life in this nation of 13 million relentlessly buffeted souls. In the marketplaces of LuandaÔÇöthe suffocating seaside capital where four million people live (up from 750,000 in 1970) without power or water, in unfinished, roofless high-rises graffitied with names of gangs like the Young Squad and the Disgusting BladesÔÇöthe street poets sing in lilting hip-hop about the ▓§ż▒│┘│▄▓╣│Ž├ú┤ă , low and under their breath, so that government spies do not hear.

“Angola, my Angola,” they sing, “once so beautiful, always so fucked up.”

Still, Angolans tell you, they can deal with the ▓§ż▒│┘│▄▓╣│Ž├ú┤ă . What cannot be dealt with is the │Ž┤ă▓ď┤┌│▄▓§├ú┤ă, the second and more deadly half of the Angolan existential equation.

An example: Angola is one of the most heavily land-mined countries on earth. Any given former cow pasture or cassava field might contain a Soviet-issue POMZ-2 stake-mounted fragmentation mine, a Type 72 antitank mine made in China, a PP-MI-Sr II “Bouncing Betty” from the former Czechoslovakia, or an East German-made PPM2 antipersonnel blaster. Above the surface, the nearly invisible trip wires of American Claymores are set off by passing trucks. All it takes is one innocent foot stepping on one mine, as dozens do every month, to have the ▓§ż▒│┘│▄▓╣│Ž├ú┤ă rapidly mutate into the │Ž┤ă▓ď┤┌│▄▓§├ú┤ă.

But │Ž┤ă▓ď┤┌│▄▓§├ú┤ă happens. And the great ironic geology-is-destiny application of the ▓§ż▒│┘│▄▓╣│Ž├ú┤ă/│Ž┤ă▓ď┤┌│▄▓§├ú┤ă is that if Angola wasn't so naturally rich, it would be at peace. Angola remains one of the ten poorest nations on earth. Yet it has the fourth-largest diamond industry in the world, controlled by the government and various foreign diamond cartels, which generated 5.1 million carats in 2001, worth in excess of $650 million. That's not counting the proceeds from the “informal” market, which traffics in “conflict” or “blood” diamonds, often mined or stolen by UNITA forces. According to Rough Trade, a 1998 report on the Angolan diamond industry by the nongovernmental watchdog group Global Witness, UNITA realized an estimated $3.7 billion from the sale of conflict diamonds from 1992 to 1998.

Then there's the Angolan oil industry, which according to Global Witness will likely soon surpass Nigeria's as the largest producer in sub-Saharan Africa. Controlled by the Dos Santos government, the oil industry is projected to produce more than 900,000 barrels a day by the end of 2002. In 2001, oil sales accounted for 87 percent of state revenueÔÇöthat is, $3 to $5 billion. Currently 3.4 percent of all crude oil imported by the U.S. comes from Angola, nearly three times the amount imported from Kuwait before the Gulf War.

So the civil war became, to a large extent, a contest of environmental plunderÔÇöUNITA's diamonds against the MPLA's oil. The dense rainforest once covering the central and northern sections of the country has been nearly logged out. Wildlife, 50 years ago among the most abundant in Africa, has been decimated, primarily by poaching and hunting for food. Offshore oil drilling threatens the remarkably fecund Atlantic fishing grounds, fed by the cold-water Benguela Current. Numerous bird species, such as the Pulitzer's longbill and the grouse-like Gabela akalat, are beginning to disappear. In the countryside, days can go by without a bird appearing in the sky. “Everything has been eaten,” people say.

To put it mildly, the effort to return Angola to any kind of environmental normality is going to be difficult. This was obvious the day the photographer Antonin Kratochvil and I visited Qui├žama National ParkÔÇöprewar, the crown jewel of the country's 12 national parks and game reserves, 5,850 square miles of treed savanna and coastline, 44 miles south of Luanda.

We spoke to park ranger Eduardo Benguela, a large, boisterous man in a snappy uniform and pith helmet. Eduardo was happy to see us, since the park had not had any visitors in several days. Did the park have zebras? I asked. No, Eduardo replied. Were there giraffes? No. How about antelope or leopards? No, none of them. Lions? Nope. Hippos? No, they were disruptive. The Cubans shot them years ago.

Then what animals did Qui├žama have? “Elephants,” he replied. He said he had 15 elephants, which had been flown in from South Africa as part of a conservation program called Operation Noah's Ark (see “Incoming Elephants,” page 118). None of the park's few visitors had seen any of these elephants recently, Eduardo allowed, but he was reasonably sure they were still there. If any of the pachyderms had stepped on an antitank mine, he would have heard the explosion.

This, Eduardo said, was “the ▓§ż▒│┘│▄▓╣│Ž├ú┤ă.”

╠ř

ANGOLA, NEARLY TWICE the size of Texas, has become an archipelago, each city its own island, or ilha. Our plan was to drive from ilha to ilhaÔÇöto start in Luanda and move out into the countryside, to see if the land and the animals could come back from the war, the rapacious diamond mining, the no-holds-barred oil exploration. But driving was going to be almost impossible. ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° Luanda, few remember when anyone drove to anywhere from anywhere else in Angola. International demining organizations, such as the Mines Advisory Group, say it will be years before the explosives are cleared from the few remaining highways. So the only way to get around is by air. But there are no commercial flightsÔÇöthat's the situation.

To get to Saurimo, the tumbledown provincial capital of Lunda Sul, 450 miles east of the Big Ilha of Luanda, you need to get to the airport at four in the morning. Several men will then run from the shadows screaming, “Cabinda!” “Lubango!” “Huambo!” When someone yells “Saurimo!” you follow him into the sprawling barrio nearby, through narrow, garbage-strewn streets, to a tiny office lit only by a Coleman lantern, where a big, smiling man named Jorge waves a price list covered with wrinkled plastic like a truck-stop menu. Saurimo costs $150; there is no bargaining. You hand over the bills in return for a piece of tissue paper stamped, simply, “received from.”

As roosters crow, you are put on a Boeing 727 cargo planeÔÇöa good thing, since the other plane on the tarmac is a Russian-made Antonov being stocked with 55-gallon drums of gasoline. Notoriously poorly maintained and unable to stay out of the range of the shoulder-launched, heat-seeking U.S.-issue Stinger missiles favored by UNITA gunners, an Antonov carrying gas is like a flying bomb. The Boeing only has four seats, already occupied by an FAA soldier, his sleeping girlfriend, and a pair of Jehovah's Witnesses assiduously underlining passages in the Book of Ezekiel. You must ride in the windowless cargo section, where your fellow travelers are splayed out on giant sacks of sugar. With no seats, there are no seat belts, and you lie there in freezing darkness hoping the Korean-made pickup trucks in the back are properly lashed down, in case of short stops.

Saurimo is where the diamonds are. Lunda Sul is home to a large deposit of kimberlite, the pipe-shaped igneous rock formations in which diamonds take shape, and 70 percent of the stones found there are considered gem quality; diamond for diamond, that makes it one of the richest fields in the world.

However, staring down into a 100-foot-deep pit a few miles east of Saurimo, where 200 or so garimpeirosÔÇöindependent prospectorsÔÇöwork 12 hours a day with sieves and pickaxes in 95-degree heat, sifting through red mud for whatever they can find, Breakfast at Tiffany's seemed very far away.

“Welcome to hell,” said a dreadlocked man in a yellow soccer shirt with Brazilian star Ronaldo's number 9 on the back. He introduced himself as Da Consciencia das Pedras, the Conscience of the Rocks. Now 39, twice the age of most of his fellow garimpeirosÔÇöwho, at the first sight of us, had raised their shovels to the sky and shouted, “Chindele! Charuto! Chindele!” (White man! Give me a cigarette!)ÔÇöthe Conscience of the Rocks said he had “lived many lifetimes in this hole.”

The best of it was back in 1994. “I found several stones in my first month,” the Conscience reported. “You are supposed to give the first stones to the foreman, but I did not. He slept all day and his food was shit.

“I was a king,” the Conscience went on. “I had a Toyota and a quintal in Luanda, a nice house.” But it did not last. “I spent it all and my wife stole the rest.” He returned to ChyngandangalyÔÇöwhich is what the pit is called, after the first prospector to score thereÔÇöbut hadn't found a diamond in over two years.

The Conscience of the Rocks is like Chyngandangaly itself, because this hole is close to played out. Some garimpeiros have moved north, to a new and bigger hole, called Samuhondo. The digging is better there, but there are complications. Samuhondo is on the other side of the Rio Chicapa, and FAA soldiers control the rubber boats. Lazing in thatch-roofed huts, playing cards and listening to Destiny's Child tapes on their boom boxes, the FAA guys, with Vietnam-era rubrics like SUCK ON THIS scrawled on the butt ends of their Kalashnikovs, exact a heavy surcharge, usually in diamonds. Attempts to cross the river in non-army craft invite a hail of gunfire. Swimming the muddy 100-yard-wide expanse is likewise out, on account of crocodiles.

“So I am stuck. This hole is my grave,” said the Conscience of the Rocks, the reddish walls rising above him. “I only hope I am dead before I am buried in it.”

NONE OF THIS IS A PROBLEM AT CATOCA, another Lunda Sul diamond mine, about nine miles to the north. In 2001, Catoca, which is overseen by the Angola Selling Corporation (ASCORP, owned by the state and a conglomerate of foreign firms), produced 2.6 million carats, worth close to $200 million. It is the biggest kimberlite diamond mine in Angola, with its own airstrip and a well-stocked commissary, and the fourth-largest in the world.

We were under the impression that we would be allowed to enter Catoca. We had letters, one personally written by the governor of Saurimo Province, with whom we'd had a brief audience. But this was not good enough. We would need permission from “the company,” we were told.

Being barred from Catoca enraged Victor Vunge, the 30-year-old journalist we had hired as our fixer. Other journalists and NGO workers said that we should fire Victor, that he was reckless, d├ęclass├ę, and possibly fatally self-dramatizing. But we liked him. Born in Malanje, he claimed to be a leading son of local Mbundu royalty. His mother had been killed during the war, when the MPLA mistakenly bombed the hospital where she lay ill; his father had been stricken with cerebral malaria and was now “crazy.” Living in Angola did that to you, said Victor, who admitted to voting for Savimbi in the 1992 election on the premise that any change had to be for the better. This was the ultimate idiocy of Angola, he said, that “a man of the people” like himself had to cast the only vote he'd been allowed in his entire life for a murdering psychopath like Savimbi.

“Why can we not go in? Who does this mine belong to?” Victor demanded of the ASCORP representative and a government man. “You cannot allow them to steal these diamonds! This is Angola! Not Brazil! Not Russia! Not Israel! Angola!”

Now, however, peering through the barbed-wire fence into Catoca, watching truckloads of soldiers in crisply creased uniforms whiz by, Victor settled into a sullen calm. It was an outrage that all these gems were leaving the country without the building of a single hospital or school. But constant railing about the ▓§ż▒│┘│▄▓╣│Ž├ú┤ă could only go so far. Simply that the government man appeared to be a grinning idiot meant nothing. You needed to know when to shut up.

We got Victor out of there before the ▓§ż▒│┘│▄▓╣│Ž├ú┤ă degenerated any further, got back in the car, and drove to a nearby refugee camp, where 5,000 people were lined up to receive their monthly ration of maize, salt, oil, and six dried fish. There is a numbing sameness to refugee camps. The same tents and mud-brick huts, the same stunned, staring children, the same quarantined area for the lepers, the same demoralizing array of T-shirt iconographyÔÇöTweety Bird, Princess Di, Nike, M┼ítley Cr┼Şe, and Michael Jordan, the all-time refugee-T-shirt king.

But mostly people sit and wait. Indeed, the camp, which received aid from the World Food Program, was generically tagged Lugar de Reassentamento (“resettlement camp”), but the people called it A Place to Wait.

Over a cup of dense tea, Antonio Franciteo NuadjidjiÔÇöthe soba, or traditional leader, a tall, distinguished-looking 57-year-old man in a high-crowned ten-gallon hat with marlboro spelled out on the bandÔÇöexplained that he and his people were from Dala, about 150 miles to the south. They'd always lived there, working as shepherds and cow-herders, but after UNITA burned their village for the fourth time since 1984, they left and walked here. Boatless boat people marching across the waterless sea of the Angolan archipelago, many died on the way, mostly from malaria and land mines. It was humiliating, being forced to go into the fields to plant cassava and hang around waiting for handouts from stingy relief organizations, the soba said with obvious disgust.

I asked him if he could characterize what had been lost by having to leave his home to come here. The soba sat still for several moments, deep in thought. “No,” he finally said. The question was “too big.” His mind “couldn't even decide where to begin to think about” what had been lost.

Then he mentioned a dream he'd had a few nights before. He was out walking in the fields and he found a diamond. It was a giant diamond, he said, making a tennis-ball-size shape with his weathered hand. He sat and looked at the diamond for “a long time,” wondering what he would buy.

“I bought a plane. It landed over there,” the soba said, pointing to the field beyond the huts where the lepers stayed. He loaded his people on the plane and flew it back to Dala, where he built a high wall to keep UNITA out. Then he bought an armored truck, the sort the relief groups use to clear antipersonnel mines, and drove it back to the camp.

“I used that truck to smash down this place, starting here,” he said, pointing to his own thatched hut. In his dream, he drove that truck “around and around,” flattening everything, until Lugar de Reassentamento was just an empty hole in the ground. That's what the soba did with the diamond of his dreams.

IT IS WRONG TO SAY THAT CONSUMER GOODS are unavailable in Luanda. Get stuck in a traffic jam and the mall will come to you. During a stoppage at a street corner near the Prenda slumsÔÇöa dead body under a bloody sheet led to much rubberneckingÔÇöour vehicle was approached, in a five-minute period, by vendors of toothpaste, surge protectors, windshield wiper blades, condoms, baby carriages, window blinds, many kinds of lights and batteries, a Mr. Coffee, a case of yogurt, and many loaves of bread, which are always hot, since the women stack the baguettes in buckets that they balance on their heads in the noonday sun.

We were looking for where they sold the people. Or rather, for where we'd been told people were sold. The place to look was Roque (pronounced “rock”) Santeiro, the largest open-air market, or candonga, in Angola, a crowded warren of makeshift wooden stalls built upon a beachfront rubbish dump that once served as a public execution ground.

Victor made inquiries and eventually found Daniel Damingos, a sleepy-eyed, ruddily handsome 14-year-old in a soiled Garth Brooks T-shirt. Daniel, who had no idea who Garth Brooks was except that he liked his hat, had been living at the Roque for six years, ever since walking here from Benguela Province after UNITA thugs killed his parents. Sleeping on the ground behind various stalls, he sometimes sold vegetables, but mostly he sniffed gasolineÔÇöexcept on Mondays, when the market was closed and the wooden tables were cleared away and piled 20 feet high, allowing everyone not too stoned to play soccer.

Mostly it was newborn babies who were sold at the Roque, usually to people from Senegal and Mali, said Daniel, leading us to where the trade supposedly took place. It made sense, he said. Families were big, there was no food or health care, and in this Roman Catholic country, abortion was not an option. Prices varied widely; he said he'd seen babies sold for anywhere from $20 to $100, as many as five in a day. (Daniel's account of baby-selling was anecdotal, of course; although it's talked about among relief workers and journalists in Luanda, I could find no organization that had investigated such allegations.)

But the cops had been by several times that week, he said, demanding gasosasÔÇö”soft drinks,” slang for bribesÔÇöand chased everyone away. Daniel, very apologetic, suggested an alternative. Perhaps we might like to buy him.

We thought he couldn't be serious, but he was. Well, then, how much did he want for himself?

“Quanto?” Victor demanded, asserting his Mbundu class prerogatives for the moment, seemingly ready to bargain hard on our behalf.

It was a dislocating, appalling moment, considering that not far from this spot, on the docks of Luanda, whole populations looking roughly like Daniel had been sold to people looking roughly like us. If instead of 2001 it had been 1601, 1701, or 1801ÔÇöeven 1901, forced labor having not been abolished here until 1962ÔÇöwe might have been peering into Daniel's mouth to check the quality of his teeth.

“Quanto?” Victor shouted again. Daniel shrugged.

“Quanto?” Now Victor pushed him in the chest, screaming for him to stand up straight. Surely he knew how much he was worth. And just as surely, Victor shouted, he knew he was worth more than any man, no matter how rich, could pay. It was no disgrace to be a street kid in Angola. There were thousands in Luanda alone. But you had to show some self-respect. You couldn't hold yourself cheap. “Don't sit here all day sniffing gasoline!” Victor exhorted.

Then Victor told us to give Daniel 100 kwanzas, about $5. He'd taken us around, given information; he deserved to be paid for his work. Daniel pocketed the money with a nod and walked off into the clouds of dust and cooking smoke.

“Angola,” Victor whispered, looking up into the thickening gray clouds. “What a stupid country.”

╠ř

WE THOUGHT CABINDA, the small province on the north side of the mouth of the Congo River where more than 70 percent of Angola's oil comes from, would be a tropical Klondike full of horny roustabouts, hookers, cheap fun, and easy money. We were misinformed. By 7 p.m. on the evening we arrived, we had the dining room of the Maiombe Hotel, the only place to stay in the town of Cabinda, completely to ourselvesÔÇönot counting the ten underemployed waiters dressed in frayed suit jackets and black ties.

The oilmen were down the road in Malongo, at the Chevron-Texaco compound, one of those self-contained golf course/multiplex/multinational nirvanas. As per insurance requirements, the American and European drillers fly in from Luanda on the government's 727s and are choppered over to the Malongo landing pad. If any Tony LamaÐwearing Houstonian had ever set foot in Cabinda town, the clerk at the Maiombe had never seen one.

The day before, back in Luanda, we'd gone by Chevron's swank offices, amusingly located on Rua Salvador Allende (Rua Karl Marx and Rua Che Guevara are around the corner). No problem to visit Malongo, they said; our names were on the list. But when we rolled up to the gates, they weren't. We told Victor to inform the lumpen gatekeepers that as Chevron shareholders (my mother gave me ten shares for my birthday many years ago) we expected to be shown the facility immediately. Instead, they called in the guards from Teleservices, the private military force that protects Malongo. We made a stink, but it got us nowhere, and Teleservices turned us away.

Not that we really needed to see Malongo. You could guess what they had in there, down to the iceberg lettuce and jars of French's mustard. The reaction of the few Cabindans who had actually been inside the stucco walls was more to the point. Our driver, a morose part-time schoolteacher named Antonio, said it was a veritable zoo. “They have many animals,” he marveled. Monkeys ran wild inside the compound, swinging from trees. One had even run alongside his car, jumped on the hood, and pressed its red butt flush against the windshield. Cabinda, formerly a densely covered rainforest, had once been overrun by monkeys, but Antonio hadn't seen one since he was a child.

Driving back to town, we came upon several people crowded around a large, metal-framed bed. Almost lost in the folds of a frilly pink-and-blue blanket lay the body of an eight-year-old boy, dead of malaria. This wake was a last chance to see the boy “in this sad life,” said a squat man sitting by the boy's body. “Many children die of malaria here,” the man added. “This is why AIDS is not as bad here as the rest of Africa. With war and mosquitoes, people die before they have a chance to die of having sex.”

The man introduced himself as “Mr. Belichnor Tati, relative of the deceased, political officer of FLEC.” FLEC is the Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda, which has been fighting a low-level war to secede from Angola since 1963. What distinguishes the province's claim to self-determination is its tremendous offshore oil reserves. If CabindaÔÇötwice the size of Rhode Island, with a population of 168,000ÔÇöachieved independence, it would instantly be transformed from a poor, embittered possession into a nation with the highest per capita income in Africa.

Worst to first: This was Cabinda's unprecedented version of the ▓§ż▒│┘│▄▓╣│Ž├ú┤ă, Tati explained, as we left the wake and walked across the highway to the Atlantic shoreline. The sky was gray. A dozen offshore rigs dotted the misty horizon, interspersed with plumes of fire jumping from the ocean's surface to vent flaring gas, which often attends offshore drilling. “Fire on the water,” said Tati, shaking his shaved head at what he took to be an affront to nature. Off in the distance was a giant tanker.

“They take the oil straight from the rigs, put it in the boat, and sail away. We never see it, except for this,” Tati said, looking down at the rainbow-slicked waves and the blackened sand. Only a few weeks before there had been a major spill. It was particularly galling to him that the MPLA used the enclave's oil money to beat UNITA. “Without Cabinda the MPLA is nothing,” he said.

FLEC was patient, but they couldn't wait forever. Recently they'd captured several Portuguese construction workers involved with a logging operation to the north. “Two are still in the bush,” Tati said, an unsettling smile crossing his broad face. Kidnapping foreign nationals was “a good tactic” for FLEC, he added, since it brought revenue and attention. Until now, the group had preferred to snatch Portuguese, “because of history,” he said. But history had changed, bringing new enemies.

“It is the Americans now,” he said. “We will have to put fire on American cars, like the flames out in the ocean. We have to make them listen.” (No Americans have been attacked or kidnapped in Cabinda since 1992.) Then Tati turned to us. “You have American passports, and you come here as tourists. Alone, without the Teleservice guards? Without weapons? Is that brave, or stupid?” It was a question left unanswered as we got back into the car, drove to the deserted hotel, and locked the door, for all the good it might have done.

╠ř

PROBABLY IT WASN'T the smartest thing, a chindele walking the streets of Luanda alone before dawn. But I couldn't sleep.

We'd only gotten back from Cabinda the day before, and then spent the better part of the evening driving the deeply rutted streets of Luanda, looking for some good music. We first stopped in at the Chihuahua disco, where the well-dressed sons and spectacularly beautiful daughters of the MPLA elite do the kizomba, Angola's elegant tango-like dance. Victor, of course, was outraged by this cologne-drenched panorama of privilege. “Afro-trash! This is no place for a journalist!” he fumed above the din, demanding we leave.

So we headed to an open-air party spot frequented by Bakongo refugees from the north, where we sat, listening to the music and buying Castle beers for the girls. Bakongo music is more forgiving than the kizomba. This suited the former FAA soldier standing near us. He was a land mine victim, his left leg blown off at the knee. Still, his disability did not prevent him from gyrating mightily on his crutch. Before his injury, he and his girlfriend had been kizomba champions, he told us, “but now if I do the kizomba, I fall over.”

It was still dark when I went out, the stars bright in the sky. Astronomy is always improved by bad power grids. Looking up, I thought of a comment made to me by Moty Kramash, an Israeli who ran the ASCORP office downtown. It was an outrage that international groups made such a fuss over “conflict” diamonds when the oil was worth so much more, Moty had said.

He understood it, he supposed, because “there is something about a diamond.” If you looked at the sky, he said with sudden sentimentality, the black oil would surround the diamond stars. “But oil is slimy. You pour it into an engine, wipe your hands to get it off,” Moty said. “People don't wish on oil, they wish on stars, and maybe those wishes will come true, even in Angola.”

Maybe. Amid the early morning cool and quiet, Luanda looked serene, even airy. A bowl of hills set around a perfect sweep of bay, the city had more than a hint of Rio about it. There was even talk of gentrification. Recently the government had forcibly removed thousands from the Boa Vista musseque on the seaside cliffs near Roque Santeiro. The cliffs were eroding, authorities said. But everyone knew the boa vistaÔÇögood viewÔÇöwas too beautiful to leave to slum dwellers. The words “real estate” had begun to dot polite conversation. The aim was to buy at “before-peace prices.”

The sun was edging up as I reached the Marginal, the once-grand boulevard that skirts Luanda Bay. I walked around awhile and then went by the Biqer bar for a coffee. A rundown place with unwashed windows that reach to the 25-foot ceilings, the Biqer (pronounced “BEE-ker”) is known as “the journalist bar.” One table, its six chairs leaning against the coffee-stained top, is eternally reserved for “the dead scribblers.” Ricardo Manuel was already there, sitting in his usual seat, wearing his argyle vest and beret, eating breakfast. Manager of a bookshop down the street and author of numerous works, including the recent Cronica de Uma Cidade, Vol. 2, sketches of “the unusual people I meet in a day in Luanda,” the 65-year-old first came to Angola from Lisbon in 1964.

“I was a settler,” he said, gently mocking the term the Portuguese used to describe themselves. I asked Ricardo about the famous episode in Another Day of Life, Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuscinski's account of the approach of the rebels and the hasty Portuguese evacuation in 1975.

“The city was closed and sentenced to death,” Kapuscinski wrote. “People ran around nervously, in a hurry…. They didn't want Angola. They had had enough of the country, which was supposed to be the Promised Land but had brought them disenchantment and abasement…. Everybody was busy building crates. Mountains of boards and plywood were brought in,” which made dusty Luanda “smell like a flourishing forest…the city of crates.”

Ricardo's eyes lit behind quarter-inch-thick glasses. “My things were in those crates,” he said. But he decided to stay in Angola when 350,000 people, including almost everyone he knew, left.

“I liked Angola,” he said, explaining why he stayed, “but there was so much panic, so much fear…I remember sitting in my house trying to decide what to do. From the TV I heard the voice of Agostinho Neto. He was giving a speech declaring Angola's independence. But I could not see him. The screen was totally white.

“That's where I was when my friend came to see me. Peter. My black friend. He'd gone to the coast and caught several fish. He brought them to me, as a gift, because I was leaving. I invited Peter in and he sat down. We were there together and the TV fixed itself. It wasn't only white now, it was black and white. You could see the picture: Agostinho Neto giving his speech. So we cooked the fish, had some beers, and sat there watching.

“I made up my mind to stay in Angola,” he said. “I have been here almost 40 years now, some good, many, many bad. But this is my place.” Whenever the ▓§ż▒│┘│▄▓╣│Ž├ú┤ă threatens to become the │Ž┤ă▓ď┤┌│▄▓§├ú┤ă, Ricardo thinks of the time he decided to stay in Angola. “It helps,” he said.

╠ř

LATER THAT DAY, our last in the country, we decided to take a ride down the coast. The road is considered safe until the town of Sumbe. That's about 180 miles, the longest stretch of open road in the Angolan archipelago, plenty of time to crank up the radio (Nelly's rap with the refrain “It must be the money” was huge) and pretend you're driving any coastline, anywhere. We weren't going far, just an hour past the hideous garbage mountains of the Rocha Pinta musseque and the massive fenced-in estate of Futungo, where Dos Santos lives, to the slave museum.

Set out on an ocean point, the slave museum does not have many exhibitsÔÇösome rusted neck irons, a corkscrew-shaped whip known as a chicotteÔÇöbut these few objects are chilling. A haphazardly hung line drawing of a manacled African beseeching a diffident Portuguese trader, “Am I not a man and a brother?” is enough to set you weeping. You pay your five kwanzas to the attendant, who does not look up from his comic book, and walk out into the late afternoon sunlight feeling shame, anger, and humility.

A group of Pentecostals were dancing and singing on the beach that afternoon. Watching them, I got into a conversation with Belmiro Teixeira, who had hitched a ride down to the beach from Rocha Pinta along with his wife, Milla. They were a slick pair. Belmiro was marvelously attired in yellow shoes, green-and-black check slacks, and a snazzy tangerine guayabera. Milla, sleek and long-legged in chartreuse capri pants with a stretchy aqua top, had her hair done up in crisscrossing cornrows.

Belmiro listened closely to the singers for a moment and shook his head. “They say the next world is better, but how do they know?” he asked. He went to church too, but he was “an optimist…a believer in the future. Right here, right now.”

It was a lesson he had learned from “my own life,” he said. After failing to make the Angolan national basketball team, which played the American Dream Team in the 1992 Olympics, Belmiro had been drummed into the UNITA army. He ran away, only to be caught by government forces and made to fight for them. Wounded near Ondjiva, he hung around the Namibian border for two years before coming up to Luanda. “If I could live through that,” Belmiro said, “I knew everything will be good.”

Now 32, Belmiro had a five-year plan to become a millionaire in the rebuilding of a new Angola. His first instinct was to go into the glass business. There was a shortage; almost every plate-glass window in the country had been shattered. “Glass is smart,” he'd thought.”I'll make glass.” But glass cannot be made in a musseque backyard. A factory is needed. This meant money and permitsÔÇöalways a problem.

Then the unfinished building that Milla's family had been living in burned down. Her brother, who died in the fire, had rigged an illegal electrical hookup to the power lines and something had gone wrong. This got Belmiro thinking. If the government could not provide safe power to everyone, Angolans could make their own. At the time, Internet access was becoming more widespread, so Belmiro found some Web sites selling solar energy panel kits. A place in Finland had good prices. If he could sell these kits cheaply enough, he could distribute them around the country. If anything in Angola was truly free, it was sunlight. The MPLA, Chevron, UNITA, and the rest could not control the sun.

It was all still in “the planning stage,” though, Belmiro said. He needed some investment. But this was an excellent time to be thinking solar. Everyone was talking about the upcoming total eclipse. Its path would pass right over Angola.

“The sun will go out. It will make a big hole in the sky,” Belmiro said. “But it will come back. Like Angola. At least, that is the hope.”

╠ř

ON PAPER, Angola's 12 national parks and reserves take up 31,600 square milesÔÇöroughly 7 percent of the country. The problem is, no one really knows how many animals are still roaming around in them. Now, given the recent cease-fire, wildlife biologists are eager to get back in there and see what has survived. The entry point is Qui├žama National Park, 44 miles south of Luanda.

“This park used to have more than 4,000 elephants, 6,000 forest buffaloes, and numerous other wildlife, but it was all destroyed,” laments Wouter van Hoven, 54, a professor at the University of Pretoria's Centre for Wildlife Management. Van Hoven heads the Kissama Foundation, a conservation group formed by the Angolan government in 1996 to resuscitate the country's park system.

To repopulate Qui├žama, the foundation launched Operation Noah's Ark. Since 2000, 34 elephants, 14 zebras, four giraffes, 18 ostriches, and 12 each of Livingston eland, kudu, and blue wildebeests have been airlifted from neighboring Botswana and South Africa. Next June, van Hoven plans to make history with the largest international wildlife relocation ever attempted: 200 elephants and about 200 other animals riding first-class aboard a South African navy supply ship. Qui├žama is also slouching towards eco-tourism: It's got the only game lodge currently functioning in Angola and a contingent of 60 former soldiers who have been retrained as game wardens.

This August, van Hoven and Richard Estes, a research associate with the Smithsonian Conservation and Research Center, plan to lead an expedition to survey Luando Integral Nature Reserve and Cangandala National Park for any sign of the rare giant sable antelope, Angola's equivalent of the bald eagle. The former commander of the Angolan army also will be along to steer them clear of minefields. “I don't think they're all wiped out,” says van Hoven of the sable, which remains prized by poachers for its long, curved horns. “But we want to make sure that this animal does not go extinct.”

╠ř