LOOKING UP AT THE FAT, GRAY SKY, it was hard to tell when, or even if, dusk had arrived. Looking down, it was easy. One minute the water beneath our paddles was the color of tea; the next, it was black. We pushed on around a few more bends, then beached the canoes on a riverbank at a clearing in the forest.

Gabon National Parks

The first night's campsite

The first night's campsiteGabon National Parks

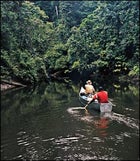

Boyer (in the bow) and Mbina paddle one of the aluminum vaches de mer.

Boyer (in the bow) and Mbina paddle one of the aluminum vaches de mer.Gabon National Parks

From left, Baert, the author, and Boyer walk their boats through a shallow section on day six.

From left, Baert, the author, and Boyer walk their boats through a shallow section on day six.Gabon National Parks

On day two, a bull elephant with massive tusks charged from the forest, coming within 20 feet of the lead canoes.

On day two, a bull elephant with massive tusks charged from the forest, coming within 20 feet of the lead canoes.Gabon, Africa

Gabon map by Shout

Gabon map by ShoutOnly Morgan Gnoundou┬ŚMor-GAHN, he pronounced it, ├á la fran├žaise┬Śhad any energy left. He cleared space for the tents with his machete, got a fire going, put a pot on to boil, and then bounded down to the river to dredge for crevettes┬Ślittle shrimp with which to bait his fishing line. Sprawled on our Therm-a-Rests, the rest of us watched in awe.

It was early August, dry season in Gabon. That morning, eight of us, in four canoes, had set out from an abandoned logging camp on the upper Djidji River not far from the Congo border. The plan was to paddle downstream 100 or so miles to a take-out just above a spectacular cataract called Djidji Falls. In the process, we'd traverse the entire roadless expanse of 1,158-square-mile Ivindo National Park. Like all 13 of Gabon's national parks, it was created ex nihilo just over four years ago, largely at the urging of the Wildlife Conservation Society, the international nonprofit headquartered at the Bronx Zoo. No one, to our knowledge, had ever paddled the length of the Djidji before, but our real mission was to evaluate the river's touristic potential┬Śsomething the WCS program director for Gabon, English-born biologist Lee White, was banking on.

“It's not a whitewater river; it's a wildlife river,” White had told me a few days earlier, at his office in Gabon's capital, Libreville. “And I think it could be the premier wildlife river in equatorial Africa.”

Sitting by the fire that first evening, I had my doubts. We'd seen animals, all right: monitor lizards, unidentifiable monkeys, and a large red forest antelope called a sitatunga, head up and stock still, as if posing in a diorama at the American Museum of Natural History. And we'd seen fantastic birds: sapphire-blue kingfishers, dinosaurish hornbills, flocks of gray parrots, and a huge, honking, iridescent thing called a hadada ibis.

But, truth be told, what we'd mostly seen were trees┬Śfallen trees. Every 50 yards, it seemed, another giant mossy trunk lay across the river, blocking our path. Sometimes there was nothing to do but lift and shove our vessels straight over the top, Fitzcarraldo style. With two of the canoes, slender plastic things improbably mail-ordered from L.L. Bean, that was at least a semifeasible proposition. But the other two were big aluminum johnboats with square transoms┬Świder, more heavily laden, and about as portable as cast-iron bathtubs. Sometimes it took five or six of us, balancing precariously on branches and slippery trunks, to heave them over. We took to calling them “les vaches de mer“┬Śthe sea cows.

Then there were the snakes. The day before, while on a short pre-trip reconnaissance cruise, Gnoundou and Christian Mbina, a Gabonese environmentalist, had been hacking their way through a brambly snag a few hundred yards from the put-in when a fat black-and-tan snake dropped into the canoe┬Śwhereupon Mbina leaped out. Malcolm Starkey, a WCS project director for two of Gabon's parks, and our designated naturalist, was too busy laughing to identify the beast. “But,” he said cheerily, “I'm 90 percent certain it wasn't venomous.”

Less than reassured, we'd approached our first log crossings with a certain delicacy. But as the day wore on, it got harder and harder to worry. Ninety percent was good enough┬Śthe main thing was to keep the boats moving, a point that was driven home the first night as we sat sipping Scotch by the fire. “So, how far did we get?” our nominal leader, Bryan Curran, the director of projects for WCS Gabon, asked our navigator, Mark Boyer, a map specialist from the WCS office in New York. Boyer punched a few buttons on his GPS and raised his eyebrows dramatically. “It looks like we've covered a grand total of 4.8 kilometers,” he said. “Of course, that's as the crow flies; we probably did twice that over the ground.”

A stony silence ensued. We'd planned on spending a week on the river┬Śwhich meant making 20 to 25 kilometers (12 to 15 miles) a day.Finally, Starkey spoke. “Hmmm,” he said, trying to sound chipper. “Where are we on the map?” Before the trip, Boyer had laboriously created and laminated a set of custom maps by combining some old topos from French colonial days with more recent data gathered by a NASA shuttle mission. He pulled the first sheet out of his daypack, squinted at his GPS again, and laughed. “We're not yet on it,” he said.

IN SEPTEMBER 2002, at the World Summit on Sustainable Development, in Johannesburg, South Africa, the famously diminutive president of Gabon, Omar Bongo, made a startling pledge: His Colorado-size nation, long known for its oil fields, would create a system of 13 national parks that together would constitute more than 10,000 square miles of equatorial rainforest┬Śbetter than a tenth of the country's total land mass.

Gabon's virgin forests and indigenous wildlife, including the world's largest remaining population of forest elephants and the second-largest of gorillas and chimpanzees, had lately come to the world's attention via the exploits of WCS biologist Mike Fay, who traversed the country on foot as part of his 1,200-mile Megatransect. Unlike most of its neighbors, Gabon seemed to be in a position to afford its parks: With proven oil reserves of 2.5 billion barrels and a population of fewer than 1.5 million, the country enjoys a per capita income of $5,900 a year, approximately four times higher than the average for most sub-Saharan nations. Still, no one had expected Bongo to make such an extravagant gesture. Percentagewise, a WCS press release noted, only Costa Rica has set aside more land for conservation, though its total park acreage is much smaller. WCS committed more than $12 million over three years┬Śabout half of it foreign-aid money drawn from the $53 million that the U.S. government gave for the Congo Basin Forest Initiative in 2002┬Śto help Gabon with the project. No logging or mining would be allowed in the parks, and development would be limited to small, eco-friendly tourism ventures and research facilities.

“By creating these national parks, we will develop a viable alternative to simple exploitation of natural resources that will promote the preservation of our environment,” Bongo said. “Already there is a broad consensus that Gabon has the potential to become a natural mecca, attracting pilgrims from the four points of the compass in search of the last remaining natural wonders on earth.”

Given the press coverage that Bongo's country has received ever since, you might be forgiven for thinking that the floodgates had opened. Gabon's parks have been glowingly written up everywhere from The New York Times to O: The Oprah Magazine, whose editors put it on the list of “Five Places to See in Your Lifetime.” In short, it's hot. So hot that, according to White, within ten years the country could conceivably see more than 100,000 visitors annually.

If you do actually get to Gabon, however┬Śand that's not easy, given the distance, exorbitant airfares, and the inconvenient fact that the national carrier, Air Gabon, shut down last March┬Śyou'll come away with a slightly different take.

“Right now, there are 1,500 real tourists a year, maybe 2,000,” says Patrice Pasquier, a Frenchman who runs Mistral Voyages, one of the country's few full-service travel agencies. “Let's be frank. I don't see 100,000 or even 50,000 in ten years' time. How many rooms [in the parks] would that take? Fifteen hundred? How many are there now? Not even 100. And let's not even talk about the state of our infrastructure.”

The problem isn't limited to a lack of planes or rooms or roads. The Gabonese themselves may not be ready for the service business. “We envision a top-of-the-line client, but first we must identify the levels to which people must be trained,” says Franck Ndjimbi, marketing chief for the Conseil National des Parcs Nationaux.

“The long-term success of the parks is linked to the success of tourism,” says White. “We're going to have to change the mentality, to the point where the Gabonese actually smile at you. That's our job over the next ten years.”

It's not just the Gabonese who need convincing. A couple of months before we set off down the Djidji, I went to the Bronx Zoo to listen to White and another major player on the Gabon project, John Gwynne, make a lunchtime presentation to the WCS staff. White, 41, was one of the driving forces behind Bongo's decision to create the park system; his 2001 proposal to protect important Gabonese wilderness areas was adopted by the president virtually in its entirety. Gwynne, 58, is not an Africa specialist at all, nor even a trained scientist, but an artist and landscape architect who runs the zoo's Exhibitions and Graphic Arts Department.

At the time Bongo created the parks, White noted, Gabon's oil production had peaked and the government was beginning to think about the transition to a diversified economy. “Like it or not,” he said, “they've decided it is an economic project.”

Then it was Gwynne's turn to speak. The first step, he said, was to create a new “global destination”: the African Rainforest. “Yes, at first it's a wall of green, and we have to part that┬Śit's critical to see animals,” he said. “But we have to look to Costa Rica's success, presenting the overall experience as much as the animals.” There was, he added, one more challenge: “This is a place where chimps and gorillas haven't seen people. They're not afraid. How do we bring thousands in without screwing up the Garden of Eden?”

An hour went by, and only a handful of people left. The crowd seemed intrigued but skeptical. It was a big step, a conservation-and-research organization taking on a tourism project, welcoming Mammon to the temple.

“How do you bring in investors and not lose control?” someone asked.

“What are your standards for ecotourism?” another wanted to know. “It's like the word healthy on a cereal box┬Śwhat does it mean?”

Those were the specific questions. The bigger question, the one that hung in the air as the meeting broke up, was the same one we'd be asking two months later on the banks of the Djidji: Are we getting in over our heads here?

TOWARD NOON on day two, as Bruno Baert, the director of logistics for WCS Gabon, and I were attempting to force one of the vaches through yet another snag, we looked downriver to see one of the faster green boats signaling to us. Something was happening around the next bend, but by the time we caught up, it was all over.

The two lead canoes had noticed a great gray boulder set back in the high sawgrass. Suddenly the boulder had exploded in a full-on charge, right down to the edge of the river┬Śa bull elephant with flared ears and magnificent tusks that had somehow escaped the poacher's knife. Then, with an imperious snort, he'd disappeared into the forest. The four had been just 20 feet away and were still reeling from an experience that, as Boyer put it, was “so real it seemed fake.”

Baert and I groaned and resolved to paddle harder. But an hour later, the same thing happened┬Śanother elephant sighting, with us just out of range behind. No charge this time, the green-boaters assured us. Nothing special. Baert stood up. “I want to see an ay-lay-phant,” he said. “I need to see an ay-lay-phant.”

By the end of the day we'd covered five miles as the crow flies and nine over the ground┬Śalmost twice our first day's total but still not nearly enough, we thought, to squeeze the Djidji into a single week.

And yet at some point that evening my attitude changed. It helped that our campsite was perfect, an old poacher's camp on a promontory above the confluence of a small tributary. The bloodsucking tsetse flies that had plagued us all day had vanished, and the eerie daytime silence of the forest gave way to the amazing cacophony of the African night: the pounding chorus of a bat colony, the scream of the tree hyrax, and a distant timpani-like sound that Starkey and Curran said was a gorilla pounding its chest. The hissing fire; the soft grunts of Baert and Gnoundou as they hooked and landed perch, catfish, and the primitively scaled capitaine; the unbroken wildness beyond┬Śthis was what camping in the equatorial rainforest was meant to be.

Alex Tehrani, the photographer, must have been similarly inspired by that exquisite moment, because he jumped up, grabbed a tripod out of the tent we were sharing, and walked a few feet into the forest to take some long-exposure shots. A minute later I heard him call out sharply.

“Ow,” he said. “Damn! Fuck!“

Then, a moment later, the one phrase I wanted to hear even less than “snake in the boat”:

The bites hurt, but the sting didn't last. “They're not really a problem unless you're tied to a tree,” Curran said. So once Tehrani had de-anted himself, we crept back to the edge of the clearing for another look. The column had by this time overrun our unzipped tent┬Śthere was nothing to do but pick it up, shake everything out of it, and then hold it over the fire and let the smoke drive out the last of the interlopers. A particularly gruesome tableau was formed by my muddy Tevas, which were completely encrusted by a wriggling layer of ants┬Śapparently there was something in the river clay they had to have.

Later, lying in the tent, I could hear the army moving over the leaves of the forest floor┬Śa million crinkly footsteps, like high-pitched rain. In the morning, we awoke to find my sandals picked clean and the ants long gone.

WHILE WE MIGHT HAVE BEEN the first team to attempt a complete descent of the Djidji, we were hardly the first people to travel on it. Downstream of the put-in, we'd noticed old machete scars and bits of cord on some of the overhanging branches┬Śan indication that workers from the logging camp had likely come this way in search of meat. Another good indication: On the floor of one of the abandoned cabins, we'd found a photo of a grinning Congolese worker holding a bloody pair of elephant tusks. And then there was the mysterious Joseph Okouyi, a Gabonese doctoral candidate studying red river hogs, who had recently established a research camp halfway down the Djidji, at the very center of Ivindo National Park, and who, in fact, had been scheduled to join us but dropped out at the last minute.

Curran was anxious to make it to Okouyi's camp by the end of day three┬Ścrucial timing, he figured, if we were going to make the train back to Libreville by week's end. But the log crossings were

About noon on the next day, we arrived at a place┬Śa wide spot in the river┬Śthat felt somehow different. There was more sky, and shrubs instead of trees, and the banks of the river were littered with a mad profusion of tracks and dung, including gorilla and leopard, Starkey said. It was an obvious crossroads, and after we'd floated through it, he pulled over to the side and motioned for the rest of us to stop.

“The wind is in our favor right now,” he said. “If we go back upstream and sit behind those trees, I think the chances are good we'll see something within the hour.”

It was the perfect call. No sooner were we out of the boats and installed in our impromptu blind than two elephants materialized out of the brush about 50 yards downstream, a mother and a baby whose age Starkey estimated at one year. They stood on the bank for a moment, then swayingly moved into the river. The place was a “saline,” Starkey explained; there was some kind of salt in the clay soil that the elephants loved. Rather than eat the soil, they sluiced a slurry of it back and forth in their trunks to extract its briny essence.

We crouched cautiously out of view at first, but when it became clear that the elephants couldn't see us, we stepped forward boldly, cameras snapping. A few minutes later, another mother and calf, this one about three, appeared and joined the first pair in the river, and then, perhaps more remarkably, the sun came out for the first time all week. Gnoundou took a canoe and paddled down to within about 20 yards of the grouping. The two cows looked up, sensing something, but then went back to their sluicing. Gnoundou waded in even closer, and Tehrani followed him, his camera out. “This is crazy,” he said, glancing back at the rest of us and grinning from ear to ear.

This was it, and we all knew it: the primordial Djidji experience that White had been talking about. The canoes, the sweet-flowing river, the elephants' fissured gray flanks glistening like wet stone in the warm sun.

That afternoon, as the Djidji whisked us westward, we analyzed the tourist potential of what we'd already dubbed Plage des ├ël├ęphants (“Elephant Beach”). It was an obvious attraction within the park, a riverine version of Langou├ę Bai┬Śthe vast, grassy clearing in the southern part of the park that was famously frequented by elephants and gorillas. The first issue was how to get people there; the only alternative to three and a half days of log-hopping hell seemed to be a road. But of course a road would mean access for everybody┬Śand everybody, Starkey pointed out, “means poachers.”

At dusk we came upon a snag that had been chainsawed┬Śa sure sign that we were approaching Okouyi's camp. I'd already conjured an image of the place in my mind: a small clearing by the side of the river with a few old canvas tents pitched beneath the limbs of some massive tree. Instead, we rounded a corner and beheld something truly shocking: a steep and completely clear-cut hillside littered with giant brush piles and the trunks of felled trees. Two wooden buildings had been erected and a third was under construction. Behind the first clearing was a second of similar size.

Curran was furious. Okouyi had “cut far more trees than he was supposed to,” he said. Boyer was appalled. He'd imagined the camp as a potential site for one of John Gwynne's eco-lodges, but that seemed out of the question now┬Śno tourist was going to come to the rainforest to look at a bunch of stumps.

No one was around, but the ashes in the firepit were still warm. I proposed that we camp there; it was late, Okouyi and his researchers would soon be returning, and we could get the full story. But no one else wanted to stay, so we shoved off and made camp a half-mile downstream. A short while later we heard a jarring sound┬Śthe whine of an outboard┬Śand then a long dugout with six men in it came flying around the bend. Spotting our canoes, the helmsman cut the throttle and ducked behind a snag on the opposite bank, then pulled out a minute later and slowly approached.

It was indeed Okouyi's crew, returning from a day walking transects in the western end of the park, but Okouyi himself, they told us, was in Makokou on business. Curran nodded curtly. “Why did you cut down all those trees?” he asked. “You know this is a national park.” The men stared blankly, not sure how to respond. “And what is the meaning of that second clearing behind the camp?”

“Plantation,” one of the men said.

Curran shook his head disgustedly. “You tell Joseph . . .” He stopped, then went on. “You tell him we need to talk.”

A FEW MILES BELOW Okouyi's camp, a major tributary joins the Djidji from the north. The river broadens and then begins stacking up in a series of oxbows. So there were far fewer snags the next day┬Śonly the biggest fallen trees could block the river's width┬Śand we started to make up for lost time. I was consigned to a vache with Boyer, and we fell steadily behind the lead boats, then finally stopped worrying about seeing wildlife. Boyer took out his fly rod and made some practice casts under the overhanging boughs along the bank.

On day six I wound up in a green boat with a new partner, Christian Mbina. We hadn't talked much┬Śhe was a serious guy who avoided the campfire, instead tucking into his tent after dinner to read the Bible. He wasn't a WCS employee but ran his own NGO, ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° Sans Frontieres, whose main mission was to take schoolchildren to the beach in Pongara National Park, just outside of Libreville, a prime nesting site for leatherback turtles. He also had an environmentally focused show on Gabonese TV called ├ça Se Passe Ici (“It Happens Here“). Still, he confessed, he wasn't altogether thrilled about the way his career was going. There wasn't enough money in it and, worse, not enough opportunity.

“I think most people who think about it are proud of the parks,” Mbina said of his fellow Gabonese. “At the same time, they say, ┬ĹThey give us the money, the U.S., but what do they do with it?' Look at the WCS project directors in each of their parks┬Śevery one of them is a foreigner. Why? Aren't there any Gabonese who can do that job?”

Mbina wasn't the only skeptic. “This is a country where we want one thing but also the other,” a Gabonese eco-activist named Marc Ona had told me in Libreville. “The parks are a good project to show to the outside world, but to take logging permits away for something long-term is a huge gamble. It won't pay off for 10 or 20 years, if ever,” he said. “And┬Ślet's be honest┬ŚGabon is not Kenya. You can go 100 kilometers without seeing anything.”

The next afternoon, the pace of the river began to accelerate. We were approaching the edge of the escarpment, where the Djidji tumbled down to meet Gabon's biggest river, the Ogoou├ę. There were more rocks now and long riffles that gave the best canoeing of the trip, then, suddenly, real rapids. We proceeded cautiously, lining the boats through difficult sections and laboriously portaging them around one thundering six-foot waterfall. The thought that ran through all of our heads was, If it's borderline now, at the height of the dry season, what happens when it starts to rain?

By dark, Boyer's GPS told us we were just a few miles, as the crow flies, from Djidji Falls. We camped at a rocky bend where a lone Cape buffalo eyed us warily before bolting. Curran got out the sat phone, waded out into the river for better reception, and called the WCS office in Ivindo National Park. “We should be at the take-out by 11,” he said.

But the Djidji wasn't quite ready to let us go. The next morning, our seventh on the river, we funneled into a narrow, rock-strewn channel a mile below our camp without stopping to scout it. The first three canoes made it through. The fourth, a vache piloted by Starkey, flipped and wrapped around a rock, then broke free, pinning Mbina, the bowman, against a thorn-studded pandanus trunk. I ran back up the riverbank to help yank the boat loose, then stupidly decided to float back down to my canoe instead of walking.

The water was only three feet deep, but it was moving fast. I couldn't stop myself or even get over to the bank. A minute later I was swept around a bend, pushed over a small drop, and then driven deep into a hole┬Śshockingly deep, because when I stroked for the surface, I didn't get there. Another desperate stroke and I popped up, then nearly got sucked down again into a submerged tangle of conical pandanus roots┬Śa nightmarish scenario that even now makes me wince. Instead, the current spat me sideways onto a rocky ledge where, badly shaken, I pulled myself out of the river.

Mbina and Starkey's vache was even worse off. After the boat folded around the rock, the aluminum weld running along the transom had partially given way, opening a large gap. We effected a MacGyveresque field repair, inserting a rubber strap in the hole and pounding the metal into place with a rock, and then pushed on.

Half an hour later, with the roar of the fast-approaching falls drumming in our ears, we rounded a left-hand bend and saw a most welcome sight, a crew of half a dozen park workers in coveralls and Wellingtons, smiling and beckoning us to shore. The eight of us staggered out of the canoes, and the trail crew began loading our boats and gear onto a couple of Land Cruisers. A minute later there was an excited shout: A snake was nestled beneath a drybag in the bottom of one of the boats.

It was a short hike down the escarpment to the base of Djidji Falls. There, we lounged on close-cropped green turf and took a final, celebratory swim in the Djidji. I couldn't quite focus on the WCS vision of a nearby eco-lodge; no doubt it made sense, but to me the place was just about perfect┬Śhard-earned, unexpectedly beautiful, unruined.

We drove out to the town of Ivindo on an overgrown logging road that, as soon as we left the park, became as wide and smooth as Libreville's voie express. Empty logging trucks passed us going the other way, kicking up great contrails of red dust, and rounding one corner I glimpsed the rear end of a large, dark ape scrambling into the woods on all fours┬Śthe only gorilla sighting of the trip.

Just before Ivindo, we came upon a solitary figure walking down the road, a machete in one hand and a bulging sack made of woven plastic slung over his shoulder. Strangely, for this part of the world, he didn't bother to ask for a ride or even look up as we passed.

“I know that guy,” Mbina said after we rolled by. “We stopped him last year when I was up here on patrol. He's a poacher.”

“That must be crocodile he's got,” Gnoundou said. “Anything else would bleed through the sack.”

“Unless it's been smoked,” Starkey said. According to Starkey, who'd done his thesis on the bushmeat market, the price would likely be 300 to 400 CFA francs per kilo┬Ś30 or 40 cents a pound, affordable for Gabon's non-elite. “When you compare that to chicken or beef, which is anywhere from 1,000 to 2,000 CFA,” he said, “you can appreciate what we're up against.”

Those days and nights on the Djidji stayed with me for a long time afterwards, and not just because tsetse fly bites itch like nothing else in the world. There were the army ants, Boyer's maps and Gnoundou's fresh fish bouillons, Plage des ├ël├ęphants and the waterfall, and not least the bond I'd formed with my vache mates┬Śfond memories all. But the guy with the gunnysack stayed with me, too. In the end, how different was he from us, with our own booty squirreled away in our drybags┬Śour notebooks and film canisters and memory cards? All of us want to have our crocodiles and eat them, too.

Getting There: Fly from New York City to Libreville, Gabon, for about $2,000 round-trip on Air France ().

Prime Time: June to September is the dry season, when temperatures range from 71 to 77 degrees, but Gabon can be visited year-round, since the rain that comes from October to May falls mainly at night.

Where to Go: Currently you can tour seven of Gabon's 13 national parks: Ivindo, Lop├ę, Loango, Pongara, Akanda, Monts de Cristal, and Plateaux Bat├ęk├ę. Mistral Voyages (011-241-76-0421, ) can arrange guided tours that include the forests, wetlands, and savannas of two or three parks┬Śwhere you'll likely see elephants, gorillas, crocodiles, and other wildlife. For more information, go to . Where to Stay: Loango Lodge offers seven bungalows and three suites (from $376 per person; ). The Lop├ę Hotel has 24 rooms on the banks of the Ogoou├ę River ($112 per person; book both lodges through Mistral Voyages).