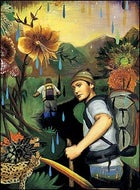

WE ALL HAVE A PLACE WE DREAM OF. We've visited it many times without ever having set foot there. It's someplace far away, someplace exotic. Although we've never seen it, we know what it looks like, for we half-created it, using a book we read, or think we read, when we were nine or ten, something we overheard at a party in a villa in Italy, and the one unforgettable image from a slide show in Bozeman. This is enough. Like a child with a refrigerator box in the backyard, a bread knife, and crayons, we've fashioned the dream of a place to which we've never been but long to go.

uganda congo

We carry it with us in the backs of our minds. It's our private dream. The way a tomboy keeps a smooth stone in her pocket, we don't share it with just anybody. It's not a place anybody else would necessarily want to go anyway.

As we grow up, this enchanted outpost can disappear inside us, if we let it. Most of us don't. Instead, we hold on to our magical place, filling in the blank spaces with facts and images we pick up along the way. Then one day something happens. The trigger may be obvious or unconsciousÔÇöno matter. The time has come to visit this place in the flesh.

I DON'T REMEMBER when I first heard of the Mountains of the Moon. Perhaps it was as far back as elementary school, when we learned that the Nile is the longest river in the worldÔÇö4,160 milesÔÇöand that Ptolemy, second-century Greek polymath, named its source the Lunae Montis, or Mountains of the Moon, the mythic snowcapped peaks that rose from the jungles of central Africa. The source remained unknown until 1858, when British explorer John Hanning Speke discovered Lake Victoria and declared it the river's origin. But it wasn't until 1888 that Henry Morton Stanley became the first European to see the highest source of the ancient river: the snow mantling the equatorial peaks of the Rwenzori (the modern name for the Mountains of the Moon), on the border of Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It was pointed out to him by an African boy who thought the peaks were covered with salt.

My next serendipitous encounter must have been in H. W. Tilman's Snow on the Equator (1937), for when you are still too young to strike out on your own, the next best thing is to read of men who did. In the early 1930s, the taciturn British explorer and his mountaineering partner Eric Shipton ventured into the Rwenzori. His descriptionsÔÇöof “the nightmare landscape,” with its constant cold drizzle, tree-size flowers, leg-swallowing mud, jungle “made grotesque by waving beards of lichen hanging from every branch,” and elusive peaks hidden in roiling mistÔÇögripped me like lust.

Then, in 1987, descending off Mount Kenya, I had an offhand conversation with a Kiwi who had just been to the fabled Rwenzori: “Times in there we was walkin' on roots suspended ten feet 'bove the ground like they was the backs of snakes,” he said. “You can't imagine it.”

But I could.

The trigger came in 2003, on the London Tube: I stumbled on a story in The Guardian about University College London geographer Richard Taylor, who, during a recent scientific expedition into Rwenzori Mountains National Park, discovered that, due to global warming, the glaciers were rapidly melting.

I had to go now, before my dreamland disappeared.

I GOT IN TOUCH with Nelson Kisaka, 31, the Kampala-based president of the Mountain Club of Uganda (MCU). Nelson said that the mountain club, much like the country itself, had been through difficult times but is in the process of rebuilding. Over e-mail, he invited me to mount a climbing expedition with the club into the peaks of the Rwenzori.

The MCU was founded in the geography department of Kampala's Makerere University in 1946. Early membersÔÇöthe vast majority of them Europeans living in UgandaÔÇöconducted numerous mountaineering and scientific expeditions to the Rwenzori. Between 1948 and 1962, the year Uganda gained independence from Britain, the MCU built a circuit of six huts, published several guidebooks, and began introducing rock and ice climbing to a fledgling nation.

But when Idi Amin came to power in 1971, all semblance of civil life vanished in Uganda. Preternaturally homicidal, Amin overthrew Prime Minister Apollo Milton Obote and then spent the next eight years executing some 300,000 civilians before being ousted by the army of Tanzania in 1979. Milton Obote returned to power in 1980 and ruled for another five bloody years, until former defense minister Yoweri Museveni's rebel army captured the capital of Kampala in January 1986 and installed Museveni as president. A benevolent yet autocratic leader, Museveni has instituted national elections (he was re-elected in 1996 and 2001) and rebuilt Uganda's economy on privatization, foreign investment, and coffee exports.

Though better developed and more politically stable than many African nations, Uganda today shares some of the same problems as its neighbors. Since 1982, AIDS has killed a million Ugandans, and Museveni's government faces several rebel insurgencies in the north, as well as sporadic fighting along the western border with the Congo. In the mid-nineties, guerrillas fighting in the Congo began using the Rwenzori as a redoubt, prompting the Ugandan government to close Rwenzori Mountains National Park in July 1997 and send in the military. The Western world heard almost nothing of this conflict until March 1999, when Congolese insurgents slaughtered eight Western tourists and a Ugandan warden in Bwindi National Park, Uganda's popular gorilla sanctuary, 100 miles south of the Rwenzori.

Trail by trail, the rebels were killed or driven out of the park, and in July 2001 Rwenzori Mountains National Park reopened. Since then, the country's tourism industry has tripled, with more than 100,000 travelers visiting the nation's ten game parks in 2003.

Yet adventure sports are luxury activities that germinate only in relatively stable conditions. After a long hiatus, the Mountain Club of Uganda has no climbing gear, and of the 300 affiliated members, only 18 are currently activeÔÇöand only a handful of those are experienced at altitude. (Most of the 300 members are Ugandans, but more than half of the active climbers are expats.) Because our expedition would be the club's first major ascent since the early days, Nelson e-mailed to ask if I might teach basic mountaineering skills.

For this I would need a partner, and I had just the man in mind: Steve Roach, 44, a mission programmer for NASA, computer science professor at the University of Texas at El Paso, and solid mountaineer. Steve is unflappable, wry, and up for anythingÔÇöhe once drove a school bus loaded with used computers to Guatemala, giving them to a school. Before I explained what my dream trip was all about, Steve said, “I'm going.” The two of us arrived in Kampala with bulging duffel bags of equipmentÔÇödonations of clothing, gear, and ropes from fellow climbers, as well as new tents from Mountain HardwearÔÇöfor the Mountain Club of Uganda.

FIVE DAYS OUT from Kampala, we cross the Bujuku River in Rwenzori Mountains National Park, hopping from one ice-fringed boulder to the next. We pull ourselves up through a stunted, moss- webbed forest to gain the lower Bigo Bog, a narrow defile between two walls of dark, wet granite. Beneath the floating hummocks of frost-glazed sedge lies a lake of mud.

In addition to our Ugandan trekking guide, Joel Nzwenge, 34, an armed national-park ranger, and 18 Ugandan porters, our team consists of Steve, me, Nelson Kisaka, and six other members of the Mountain Club of Uganda. The demographics of our group resemble those of the present-day MCU: Of the seven members, only Nelson and 26-year-old electrical engineer Eric Mugerwa are Ugandan. The rest are expats: Kenyan Ngoki Muhoho, 40, who owns her own management consulting business; Greg Smith, 24, a British economist for Uganda's Ministry of Finance; Mike Barnett, 59, an Australian project engineer in Kampala; and two YanksÔÇöGlenda Siegrist, 42, nurse for the U.S. embassy in Kampala, and her husband, Loren Hostetter, 43, an agricultural development consultant for USAID. Greg and Loren have mountaineering experience; the rest are enthusiastic novices.

It has been raining for days. Two nights ago, at the Nyabitaba hut, it was pouring so violently, the tin roof was shrieking. But when I asked Joel how the weather would affect the alpine moorlands, he said, flatly, “It is not raining.” He wasn't joking. To the BakonjoÔÇöthe people who live in the foothills of the Rwenzori and farm cassava, bananas, beans, and coffeeÔÇöit is raining only when the air is so full of water you literally can't breathe and must stay indoors.

Above the lower Bigo Bog lies the upper Bigo Bog, at 12,000 feet. When Rwenzori Mountains National Park was declared a World Heritage Site by the UN in 1994, a boardwalk was built across this swamp. Dilapidated now, yet still largely above water, it allows us to chug across the quagmire like engines on a narrow-gauge railroad, entering a landscape I have imagined since childhood.

A forest of hypertrophic plants surrounds usÔÇögiant groundsel and giant lobelia and giant heather. The giant groundsels, 25 feet tall, with their enormous, artichoke-like balls atop their furred branches, resemble Joshua trees. The giant lobelias, purplish spires of hair, stand like solemn, bearded trolls; giant heathers hover to either side like plants that have morphed into enormous mammals. It is like Little Shop of Horrors. At any moment I expect a giant groundsel to reach out and grab me, or a three-foot rosette to spread its labial leaves and speak.

This surreal terrain, as much as the summits themselves, is what drew me to the Rwenzori, and I'm in no hurry to leave. Still, it takes us only two more days to reach our alpine high camp, the Elena hut, at 14,900 feet.

That night, before our dawn attempt on Margherita, the highest summit of 16,763-foot Mount Stanley, we're all zipped up in our bags on the blackened hut floor. Due to altitude sickness, Eric, Ngoki, and Nelson will stay in the hut while the six of us make the final push.

“We should split into two roped teams,” whispers Steve. “You, Loren, and Greg. Me, Glenda, and Mike. How far did you recon today?”

“To the Stanley Plateau, I think,” I say.

“Couldn't see the peaks?” chuckles Steve. The fog, sleet drizzle, and flurries of snow have been so incessant that we haven't even laid eyes on the summits yet. We are climbing in the summer dry season, but the Rwenzori gets eight feet of precipitation a year.

The next morning we set off into an ocean of fog, as usual. Following cairns up recently deglaciated granite slabs, we reach the steep nose of the Elena Glacier, where our two teams separate.

“See you on top,” I yell to Steve, a blue ghost in the pearly opacity.

“I doubt it.”

Loren, Greg, and I make short work of the Stanley PlateauÔÇöa flat, diminishing ice capÔÇöthen cut northeast across a rock ridge to gain the Margherita Glacier. Although it is heavily crevassed, meltwater has filled in the cracks. A generation ago we would have been able to climb ice all the way to the top. Today the peak is a shattered helmet of dripping rock.

We summit before noon, eat lunch in swirling clouds, then descend to the base of the rock to find Steve's team arriving. Some swift belaying and Steve, Glenda, and Mike top out.

We're all grinning ear to ear as we crampon back down the glaciers together. At the hut, Mike confides that he's been dreaming of climbing the Rwenzori for the last 30 years. Dreams are contagious, and dreamers sometimes, serendipitously, find each other.

ONCE YOU'VE SPENT the time, money, and emotional energy to get yourself to that place you've fantasized about for decades, there's no sense in not having a good look around. So when the MCU climbers descend the next day, Steve and I stay on at the Elena hut. We have a detour in mind.

During the Mountain Club of Uganda's peak years, its most dedicated member was H. A. Osmaston, who wrote Guide to the Ruwenzori: The Mountains of the Moon in 1972. I'd obtained a photocopy, read it carefully, and made e-mail contact with Osmaston, now 84 and living in Cumbria, in northern England. In my note I suggested that there appeared to be ample room for a new route on the west face of Mount Stanley.

He responded: “I think all you say is correct. The rock should be clean of moss as it is so steep. But it is entirely in the Congo. A bullet-proof jacket would be an important addition to your kit. I don't advise it.”

According to Osmaston, the last documented ascent of the west face of Margherita was in 1956. No one really knew whether Congolese guerrillas were still using the western slope of the range as a hideout, but after talking to our portersÔÇömany of whom live in the high villages of the RwenzoriÔÇöI reasoned that if they were, they probably wouldn't bother climbing to 16,000 feet.

“I say we go have a look,” I propose.

“I say we might get ourselves killed,” replies Steve, which doesn't mean he doesn't want to go.

From Osmaston's guide, it appeared that no one had made a complete traverse of the Stanley Plateau. There was once a cabin, the Moraine hut, down on the Congo side, but Osmaston didn't know if it still existed. We figure we'll shoot for this hut, get a peek of the west face if we're lucky, and go from there.

An alpine start is requisite, but it is snowing hard the next morning. We scootch down in our bags and dream on. By nine it is snowing only lightly.

“If we're gonna go,” says Steve, heaving on his pack, “let's go.”

We retrace our steps up the Stanley Plateau, then veer left toward the pass. By chance, a hole opens in the clouds and we spot what we think is a tiny hut, then the gap closes. We cross the invisible border and descend the western Stanley Glacier until it disappears, forcing us to rappel down rock ravines. We're in the Congo now.

As the mist momentarily clears, we again spy the hut on the ridgelineÔÇöand two people standing beside it. Uh-oh. I stare through the wisps of white with all my might, trying to determine whether they are armed.

“Are they moving?” Steve's voice is a wee bit higher than normal.

“No. They're not moving.”

The mist rolls in, the guerrillas disappear, and we keep on for a closer look. We are approaching like cats now, silent, shoulders tensed, creeping low to the ground through the boulders. The mist blows off again.

“They haven't moved,” I whisper.

Steve bursts out laughing so loud I jump. “Nope. They sure haven't. Might be because one's a cairn and the other one's a giant groundsel.”

No reason now not to go for it.

When we reach it, the hut is empty but still in solid condition. We eat lunch inside with the door open for the little we can make out of the west face of Mount Stanley. The peak, 2,500 feet above, is engulfed in dark-bellied clouds. The glaciers, the icefalls, the three summitsÔÇöwe can see none of it. So what's new?

Steve strikes out up the face first, and I follow, both of us scrambling along steep, verglased granite. Gaining what we presume is the Alexandra Glacier, we rope up and simul-climb for the next three hours, occasionally sinking an ice screw. The ice is 50 or 60 degrees, and we can never see more than 100 feet above us, so we don't know where we're going, other than straight up. It sounds more daring than it is. When you're climbing properly, you're in the moment, working only with the world right at the end of your hands and feetÔÇölike a potter or a sculptor or a gymnast.

The last two pitches are a gothic castle of iceÔÇöturrets, moats, curtained walls, tenuous drawbridges. We are utterly, thankfully, alone. Everything above us and everything below us is lost in nubilated white gauze, as if this castle were suspended in the sky.

Standing beside the summit signpost, we have no view whatsoever. No hazy sea of green down in the Congo. No surrounding ridges or arêtes. No falling valleys. But that is fine. We can imagine it without even trying.

WHEN YOU FINALLY go to a place you have fictionalized for years, you know that the illusion you have so carefully constructed will vanish forever, as all dreams do when you wake up. You make it real and then it all too quickly becomes a memory. Which would be heartbreaking if, before you got home, you didn't discover that you had somehow slipped your smooth stone into another person's pocket.

We had a grand pizza party at an upscale Italian restaurant in Kampala following the expedition. The whole team was there, along with aspiring members of the MCU, young Ugandans yearning to explore the mountains. They listened to our stories of the Rwenzori, then started planning their own expedition.

The Mountain Club of Uganda is back.