THE VILLAGE OF KIONGURURIA, in Kenya’s Great Rift Valley, is a hardscrabble place, with mud huts scattered among green hills and a forlorn collection of businessesa maize-meal store, a bar, a phone exchangestrung along a potholed highway. When I stopped there on an overcast morning in late July looking for friends and family of 37-year-old Robert Njoya, whose death earlier this year has riveted Kenya, a drunken man wearing a Green Bay Packers cap staggered up and shoved his hand in my face, demanding money. Three friends sitting on a stoop burst out laughing. I gave the man 50 Kenyan shillingsabout 70 centsand he stumbled away.

Cholmondeley Trial, Kenya

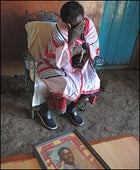

Seenoi, widow of Samson ole Sisina, a Masai who was a ranger with the Kenya Wildlife Service

Seenoi, widow of Samson ole Sisina, a Masai who was a ranger with the Kenya Wildlife ServiceCholmondeley Trial, Kenya

Mike Reagan

Mike ReaganCholmondeley Trial, Kenya

Peter Gichuhi Njuguna,left,who was with Robert Njoya on the evening he was killed, testified at Cholmondeley's trial in September.

Peter Gichuhi Njuguna,left,who was with Robert Njoya on the evening he was killed, testified at Cholmondeley's trial in September.Cholmondeley Trial, Kenya

Newspaper coverage after Cholmondeley's second arrest

Newspaper coverage after Cholmondeley's second arrestA minute later I ran into Daniel Losut, a gaunt man who told me he’d been a neighbor of the victim. He offered to take me to meet Njoya’s widow, Serah, and together we drove up a rutted path to a hut surrounded by a fence of roped branches. Just beyond an adjacent plot of corn, an unkempt hedge marked the boundary of 50,000-acre Soysambu Ranch, founded a hundred years ago by the third Lord Delamerethe legendary big-game hunter and cattle baron who moved to Kenya from Britain at the turn of the last century. Since no one was home, Losut borrowed my cell phone to try to track Serah down, but he couldn’t reach her. As we waited, on the off chance that she’d show up, I asked Losut whether reports about the dead

Late on the afternoon of May 10, 2006, as the equatorial sun sank low in the sky, Njoya, with four local men and six dogs, apparently clambered over the hedge beside his house and illegally entered the Delamere estate. At the same time, Thomas Cholmondeley, the third Lord Delamere’s 38-year-old great-grandson, set out for a walk with a friend from his colonial-era home, Jersey Hall, a five-bedroom converted cattle barn on the family’s ranch.

Just before dusk, Kenya’s two social extremes collided. The five black men emerged from a thicket, carrying bows and arrows and, over one man’s shoulders, a skinned impala. What happened next is a matter of dispute. In Cholmondeley’s telling (which has been backed up by his walking companion that afternoon, another white Kenyan named Carl Tundo), the poachers set their dogs on him and he fired four shots in self-defense from his .303 Lee Enfield riflekilling two of the animals and accidentally hitting Njoya, who was hiding behind a hedge, in the groin. Those who were with Njoya say that Cholmondeley opened fire without warning as they were carrying the dead impala toward a nearby tree. They heard several shots and fled; Njoya never made it back to his hut. Tundo says Cholmondeley bandaged the injured man with a handkerchief, yelled for a car, and told the driver to take Njoya to the nearest hospital. By the time the vehicle arrived at the hospital, Njoya had bled to death.

Losut and I waited for half an hour in front of the hut, then we got back in the car and set off in search of Njoya’s older brother James, who owns a butcher shop just off the highway. There had been rumors that this was where Njoya often took his poached animals to be butchered. When we arrived at the dank, tin-roofed shack, I found James huddled in a back room, surrounded by hanging meat and rifling through a wad of account slips. He looked at me suspiciously.

“A lot of foreign journalists have stopped here asking me questions about my brother,” he said. “Then they print lies.” I told James I was interested in hearing about Cholmondeley’s reputation among the localsthere were allegations that he had treated the people of Kiongururia harshly when he found them trespassing on his land. He said he needed to confer with the rest of the family. He asked for my cell-phone number and promised to call later that evening. I never heard back from him.

HAD THE KILLING OF ROBERT NJOYA been an isolated incident, it would probably have rated only a few lines in local newspapers. But one year earlier, on April 19, 2005, Thomas Cholmondeley (pronounced CHUM-lee) had been involved in a strikingly similar confrontation. In that incident, Samson ole Sisina, a 45-year-old ranger for the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS), was dispatched to Soysambu with two KWS corporals on an undercover mission. The three government officers were investigating whether members of the Soysambu staff were illegally shooting wild animals on the property and selling the meat. With ole Sisina at the wheel, the team arrived at the ranch in an unmarked Toyota Corolla station wagon with fake license plates. Posing as meat buyers from Nairobi, they talked their way past the security man inside the guardhouse, signed a register using false names, then drove ten minutes down a gravel road to the slaughterhouse, a low, white-painted stone building with a tin roof. Ole Sisina’s two colleagues entered, asked about buying game meat, were told that none was being sold at the ranch, then left without finding incriminating evidence.

As the KWS employees were leaving Soysambu, however, they passed a Land Rover heading into the ranch carrying a buffalo that had been shot a few hours earlier. (Cholmondeley later explained that the buffalo was a “problem animal” that had been

A few moments later, according to a police report, a Soysambu driver appeared at the nearby house of Christopher Chirchir, the ranch’s managing director. Chirchir was told that “people with guns . . . who looked like robbers” had invaded the property and taken the slaughterhouse staff hostage. Chirchir then phoned Cholmondeley at his home 100 yards away. A crack shot, Cholmondeley picked up his .357 Luger pistol and hurried down a path. As he approached the slaughterhouse, he later told police, ole Sisina appeared around a corner. In unclear circumstances, Cholmondeley fired four shots, instantly killing him with a bullet in the neck.

Immediately after the shooting, Rift Valley police confiscated Cholmondeley’s weapon and took him into custody. The next day, 50 members of ole Sisina’s family, from the Masai tribe, stormed the nearby Naivasha police station, where Cholmondeley was being held, but were driven off; hundreds of Masai also demonstrated on the highway in front of the ranch. Cholmondeley spent the next month in a filthy jail cell before Kenya’s director of public prosecution, Philip Murgor, to widespread public dismay, ordered him released, citing a lack of evidence to sustain a murder charge.

After the death of Robert Njoya, Cholmondeley was not as fortunate. Arrested hours after Njoya’s death, he was charged with murder 14 days later and dispatched to Kamiti prison, a maximum-security, British-built fortress outside Nairobi. Friends and family have closed ranks around him, forbidding the media from seeing him in prison, visiting the ranch, and talking to Chirchir, Carl Tundo, or those closest to him. If convicted, he could be hanged.

Cholmondeley’s trial began on September 25 with a four-day round of opening arguments and testimony; some observers are predicting it could last a year or more. But even before that, Kenyan bloggers were calling the courtroom drama “Kenya’s version of the O.J. Simpson trial,” both because of the voluminous amount of media coverage the case has generated and because of the starkly different views of Cholmondeley held by blacks and whites. Black Kenyans tend to believe that Cholmondeley is guilty of murder, defined by Kenyan law as homicide carried out with malice aforethought. In recent months, stories have surfaced about Cholmondeley’s alleged mistreatment of trespassers.

A September article in The New York Times named a woman who claims Cholmondeley slapped her after he caught her collecting firewood on the property. Nick Maes, a British journalist who spent a social week with Cholmondeley at Soysambu, described, in an article in the Sunday Times of London last June, “a moment of intense drama and fury” between the rancher and a Masai herdsman who had trespassed on the ranch to graze his cattlea disturbing foreshadowing of the Njoya killing. “Tom hit the brakes and leapt out of the car, yelling: ‘Get these fucking things off my land!'” Maes wrote. “He snatched a Masai cudgel from the trespasser and wielded it above his head.” The incident ended, according to the article, when Cholmondeley threw the weapon in his pickup truck and drove off.

Cholmondeley’s friends, most of them white, have proclaimed his innocence, arguing that he was defending himself in two potentially deadly confrontations in the middle of a crime wave. In the past several years, the Rift Valley has experienced a spike in violence, attributed to an influx of the poor from across rural Kenya searching for work in the booming flower industry around Lake Naivasha. Five whites have been shot dead in the past two years, most notably Joan Root, a wildlife documentary filmmaker, murdered in the bedroom of her cottage on Lake Naivasha in January 2006 by three killers wielding AK-47’s, possibly in revenge for her crusade against poaching. That same month, thieves invaded Soysambu and shot the ranch’s managing director, Chirchir, a black man, in the stomach with a Kalashnikov, seriously wounding him. Weeks before that, robbers had held up the ranch’s dairy manager, an Indian-Kenyan, at gunpoint.

“Tom is not a mad, gun-toting idiot,” I was told by one of his closest friends, who insisted on anonymity. “[The two fatal shootings were] just a terrible, terrible coincidence.”

The Cholmondeley case has provided endless fodder for the tabloidsthe Delamere heir has emerged as the man whom black Kenyans love to hatebut it has also raised larger questions about race, economic injustice, white privilege, and land distribution. The Delameres are the most prominent members of an elite group of white landowning families that profited from treaties forced on indigenous tribes by the British colonial government at the turn of the 20th century. Although many whites sold their land to black Kenyans decades ago, the few hundred big land owners who remain continue to live in a bubble of wealth and privilege, even as the vast majority of Kenya’s indigenous population is mired in poverty.

“The Delamere family owns 50,000 acres in the Rift Valley, in a country where people fight for a quarter of an acre,” I was told by Parselelo Kantai, a black Kenyan journalist who writes frequently about Rift Valley politics. “Their lives are a 1920s fantasy.”

SOYSAMBU, A MASAI NAME meaning “striped stone,” lies on the eastern shore of Lake Elementeita, one of the smallest of a dozen alkaline lakes that extend in a chain through Kenya’s Great Rift Valley, a giant seam in the earth created by a shift of tectonic plates 20 million years ago. When I drove past the lake on a late-summer morning, thousands of flamingos were basking in the shallow watera pink haze dusting Elementeita’s silver surface. A vast sweep of savanna, speckled with yellow-barked fever trees, rose gently from the lake: the Delamere ranch. Strange volcanic forms loomed along the shoreline, including a proboscis-like outcropping known as Delamere’s Nose. I turned off the highway and followed a dirt path through the bush to a metal gate and, behind it, a ramshackle guard booth. DELAMERE ESTATES, read a crude handpainted sign. NO ENTRY WITHOUT A VOUCHER. It was as far as I could go.

Until about a hundred years ago, the land I was driving through belonged to the Masai, nomadic herders whose territory extended from northeast Kenya across the Rift Valley to the Tanzania border, in the country’s southwest corner. At the turn of the last century, however, Hugh Cholmondeley, the third Lord Delamere, cast his eye on the rich grazing land on the shore of the lake. Largely to accommodate Cholmondeley and a handful of other white settlers, the British colonial government in 1904 forced Masai elders to put their thumbprints on a treaty that stripped the tribe of their ownership of the Rift Valley. The nomads were left with a divided territory, one zone south of Nairobi and the other in the highlands of Laikipia, northwest of Mount Kenya, which was taken away in 1911. In 1906, Cholmondeley purchased much of the confiscated Masai land around Lake Elementeita for little more than administrative and land-surveying costs. Even now, the property is contested. Michael Tiampati, of the Maa Civil Society Forum, a Masai activist group, insists that “the process in which the land was acquired by Delamere was fraudulent, and they are illegally there.”

Hugh Cholmondeley, Thomas’s great-grandfather, was known as a practical joker who liked to ride his horse into the lobby of the Norfolk Hotel in Nairobi, a favorite watering hole for white Kenyan ranchers, and shoot out the lightbulbs in the bar. But he was also a serious rancher, committed to “the political and agricultural future of British East Africa,” as Beryl Markham wrote in West with the Night. He built Soysambu into one of the most successful cattle ranches in the region. His son, Thomas, spent most of his adult life in advertising in London, but his grandson, Hugh (the accused Cholmondeley’s father), continues the ranching tradition. The fifth Lord Delamere, now in his seventies, has amassed 10,000 head of cattle and set up a countrywide distribution system; Delamere dairy products and beef are sold all across Kenya. Soysambu also sustains a thriving wild-animal populationabout 10,000 warthogs, impalas, buffalo, zebras, giraffes, cheetahs, and lionsand for several years the family owned a safari lodge on the shores of Lake Elementeita, called Delamere Camp, which was managed by a Kenyan hotel company.

It was here, in the wealthy enclave dubbed Happy Valley, cocooned in a world of black servants, shooting lessons, and ambles through the game-rich savanna, that Thomas Patrick Gilbert Cholmondeley came of age. Hugh Simpson, a neighbor, remembers him as “a nice boy, with a formal English upbringing, always polite, an open chap.” As a young teenager, Cholmondeley was sent by his parentshis mother, Lady Ann Delamere, is the daughter of one of Kenya’s last colonial governorsto Eton, the elite public school in southern England, and then the Royal Agriculture College, in Gloucestershire. Back in Kenya, Cholmondeley established himself as a flamboyant presence on the white Kenyan social circuit that revolves around Rift Valley ranches and the leafy Nairobi suburb of Karen, named for one of its first denizens, Karen Blixen, author of Out of Africa. Six foot four, blandly handsome, with a fringe of blond hair framing a balding pate, Cholmondeley attracted a wide circle of people like himself: wealthy white Kenyans and British expatriates who were drawn to the romance of East Africa. A friend recalls him showing up at a Nairobi wedding wearing a purple velvet suit, towering above the crowd, holding court about a walking safari he’d just taken with friends in the bush. With a large amount of cash, a fondness for women, and a taste for adventure, he struck some people as a dilettante, an overgrown teenager with a short attention span.

“He’s fun to have a drink with, but he’s not a serious person,” one acquaintance told me. “He’d say, ‘I’m going to buy a plane and fly around Africa,’ and he’d go out and get himself a single-engine Piper.”

As was the case with his great-grandfather, who was once severely mauled by a lion while hunting in the East African bush, Cholmondeley’s enthusiasms could get him into trouble. 1n 1991, according to London’s Evening Standard, during a charity motor rally, Cholmondeley’s car caught fire 50 miles from Monte Carlo, destroying part of the road and an adjacent farm, but he emerged from the accident without serious injury. Six years later, while he was hiking in the Masai Mara, a buffalo charged from the bush and attacked him. “The horn went into the back of his thigh and ripped through the back of his knee and came out his ankle,” Simon Cox, a longtime friend, told me. “But it didn’t wreck any arteries; he just lost a lot of flesh.” Cholmondeley’s injury did bring him one life-changing benefit: Cox introduced him in the hospital to Sally Brewerton, a British physician then working for Doctors Without Borders in Sudan. The couple, who married in 1998 but separated shortly before the ole Sisina killing, have two young sons, Hugh and Henry.

Cholmondeley works under his father and Chirchir as the ranch’s financial manager. His parents also live at Soysambu, in a four-bedroom house about a 15-minute drive from his. By all accounts, Cholmondeley seems to share his father and great-grandfather’s passion for the land and is fiercely protective of the property. Lord Delamere granted the producers of the 2001 film Lara Croft: Tomb Raider permission to shoot a scene at Lake Elementeita, but, at Cholmondeley’s insistence, strict rules were set about the use of vehicles along the fragile shoreline, and he monitored the filming every step of the way.

Cholmondeley’s protectiveness of the ranch also led him into an ongoing conflict with the Kenya Wildlife Service. In November 2003, the KWS banned the practice of animal culling on the country’s private ranches, claiming that the existing programin which ranchers were permitted to shoot a small amount of their wildlife each year, to prevent overgrazing and other environmental damagewas poorly controlled and that many ranchers were cheating. Connie Maina, the KWS spokesperson, told me, “The system was being abused, and the numbers of zebra, gazelles, and buffalo were dropping fast.” Cholmondeley allegedly ignored the KWS prohibitions, claiming they were hurting the ranch’s cattle. Nick Maes even joined Cholmondeley on a hunt at Soysambu, and his Sunday Times article describes the rancher bringing down a gazelle with a single shot. Cholmondeley had been appointed an honorary game warden by the KWS in the nineties, and he and fellow ranchers claimed that he had the right to shoot wild animals that he deemed a threat to his property, his cattle, or his staff.

“All the wildlife in the country belongs to the government, and KWS is the custodian,” Maina said. “You have to go with what is the law, but Tom Cholmondeley made his own rules.”

AS I TRAVELED THROUGH the verdant suburbs and gritty shanty towns of Nairobi, I was struck by the vehement antipathy among blacks toward the Delamere heir. “Tom should get the death penalty,” said my driver, Ben, a Kikuyu from central Kenya. “Nobody can shoot two people dead in one year and claim that it was self-defense. He is a killer.” Several people I talked toa taxi driver, a journalist for The Daily Nation, Kenya’s largest newspaper, a bellboy at the Norfolk Hotelreferred to Cholmondeley as a “Kenyan cowboy,” a term used to describe a particular breed of macho white Kenyan who manifests the same racially superior attitude as his colonial-era ancestors.

To some black Kenyans, however, Cholmondeley has been the victim of a rush to judgment. Philip Murgor, the chief prosecutor who dismissed Cholmondeley’s first murder charge, believes that jealousy, greed, and reverse racism all contributed to an unfair target=ing of the white rancher. After overruling the police and ordering Cholmondeley freed from jail on May 18, 2005, Murgor provoked outrage across Kenya; for that and other reasons, he says, he was fired by President Mwai Kibaki a week later. A trim, light-skinned black man,

As I sat in his cramped office in downtown Nairobi, Murgor handed me a copy of the official report filed by the Rift Valley Criminal Investigations Division (CID) shortly after the ole Sisina killing. In stilted English, the report states that the KWS ranger “ran for his dear life,” while Cholmondeley “chased him for about 61 [yards] where he eventually shot him in the neck and killed him instantly.” Cholmondeley had given the police a drastically different version of the incident, claiming that he fired at ole Sisina from some distance only after the ranger took the first shot. “I shot the man in the firm belief that he was a robber with intent to cause harm to myself and my staff,” Cholmondeley said in a statement to police. “There was no indication that he was a KWS ranger and I am most bitterly remorseful at the enormity of my mistake. I beg the authorities for leniency.”

Murgor says he learned that the police had ignored key evidence, such as the fact that several employees inside the slaughterhouse insisted that they’d heard ole Sisina’s small-caliber revolver go off before Cholmondeley fired his Luger. The deeper Murgor probed, the more convinced he became that Cholmondeley was being railroaded: He told me that he suspects that powerful politicians put “intense pressure” on the police to rush through a murder charge. “This is all about land,” Murgor told me. “The Delamere ranch is the [biggest tract of land] in the Rift Valley, and a lot of people want it.”

At the time of Kenya’s independence from Great Britain in 1963, the country’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta, guaranteed to respect the titles of the country’s white landowners, who then numbered about 3,500. Only an act of Kenya’s parliament could undo Kenyatta’s guarantee, a step that almost every political figure and lawyer I spoke to in Kenya said was highly unlikely. But, according to Murgor, some Kenyan political figures believe that prosecuting Cholmondeley on a capital-murder charge could force the family out of Kenya or oblige them to divest their land in the hope of getting more lenient treatment.

Immediately after Murgor ordered Cholmondeley released, the former prosecutor charges, the media and some politicians engaged in an orchestrated campaign to whip up a furor. OUTRAGE AS DELA MERE IS FREED OVER KILLING, declared the front page of The Daily Nationa headline that, Murgor says, was as much intended to create a stir as to report on one. In the story, ole Sisina’s brothers called the dropping of the charges a travesty of justice and insisted that “our brother’s life has been treated like that of a dog,” while Edward Nkoiboni, the councilman for the Ntulele ward, where ole Sisina lived, said, “The government has clearly demonstrated that it has two sets of laws: one for the poor and the other for the rich.”

But Cholmondeley’s own behavior, as much as the comments of politicians and the press, contributed to the heated atmosphere. The morning after his release from jail, a photograph ran on The Daily Nation‘s front page showing him sitting in the back of a police vehicle, flanked by officers, smiling jubilantly and flashing two thumbs up. His friends believe he was set up by the media to look bad. “Do you know what the Kenyan press did?” one close friend of Cholmondeley asked me. “They screamed, ‘Tom, show us your hands are free.’ So he gave them the thumbs up, and it came across as ‘Yahoo, I got away with murder.’ ” Cholmondeley reportedly also went back to his standard practice of carrying weapons around his property, despite warnings that he was under police and media scrutiny.

“Everybody who knew Tom thought he was making a mistake by carrying guns,” one friend told me.

When news broke of the Njoya shooting, it created a predictable uproar. OH NO, NOT AGAIN, screamed The Standard, Kenya’s daily tabloid. This time, according to news reports, the Rift Valley police confiscated all firearms from Cholmondeley, and politicians warned prosecutors that the consequences of another release would be disastrous. “The government goofed the last time . . . and it should be reminded that people . . . will not take things lying down this time,” former cabinet minister Anyang’ Nyong’o told The Daily Nation. At Njoya’s funeral, in May, Koigi wa Wamwere, a deputy minister of information and member of Kenya’s parliament from the town of Nakuru, urged the crowd to “take [the law] into your own hands” if Cholmondeley were released from prison.

I went to see Wamwere at his tenth-floor office in downtown Nairobi during a break from a legislative session. It was two and a half months after the Njoya shooting, and Wamwere, who had championed democracy and human rights during the repressive era of Daniel arap Moi, was still making incendiary comments about the case.

“We have a problem in Kenya,” he told me, peering through wire-rim spectacles. “These white Kenyans think that they remain the masters, and we blacks are the servants. They don’t see why they should treat blacks differently from colonial times.” A small, wiry man clad in a black Nehru jacket and black cotton pants, Wamwere shook his head when I brought up Cholmondeley’s contention that he had killed both of his victims in self-defense. “That is ridiculous,” Wamwere told me. “This man is a Kenyan cowboy and he’s not alone. Go to the flower farms in the Rift Valley and look at themcarrying pistols, swaggering around like the cowboys in Texas. That mentality has not left the white landowners. They are running around, thinking they can shoot a black as easily as they shoot a wild animal.”

Sipping from a cup of sweet milk tea, he flashed an incongruous smile. “If he were set free and people took the law into their own hands, who would blame them?” he said. “I don’t want to see that happen, but, believe me, people will be very angry. Tom Cholmondeley will be a marked man.”

HUGH SIMPSON drew on an Embassy cigarette and glanced over a curry-stained menu in an outdoor Indian restaurant just down the road from Lake Naivasha. A rugged, sunburned sculptor and outdoorsman, Simpson is a third-generation Kenyan whose Irish grandfather settled on Lake Naivasha at the turn of the last century. Ten years older than Cholmondeley, he was something of a mentor to him in his youth, later hunted with him around Kenya, and was a frequent visitor to Jersey Hall. “I’ve known Tom since he was 12 years old,” he said. “I’ve seen him close at hand, played sports with him. The image of him as a ‘Kenyan cowboy’ couldn’t be farther from the truth.”

Simpson looked me in the eye. “I don’t care what people say,” he said. “There’s no racialism in Tom at all. He’s considerate to others. He’s the right sort of person for this country. When you compare Kenya to places like Zimbabwe, we [whites] have had a very happy passage, and people such as Tom are responsible for that. He’s just been terribly unlucky.”

My meeting with Simpson had come about after days of frustration. Cholmondeley’s girlfriend, Sally Dudmesh, a British expatriate, socialite, and jewelry designer who lives in Karen at the Ngong Dairy Farm, a colonial villa featured in the film Out of Africa, had recently sent out a letter asking Cholmondeley’s circle not to talk to the media. Access to Cholmondeley’s friends had shut down almost totally, and only after pleading with intermediaries was I allowed a brief on-the-record encounter with the sculptor.

We hooked up at the Delamere Shopping Center on the Naivasha-Nakuru highway, a ramshackle collection of fast-food shops, produce stands, and a gas station that Cholmondeley started up about five years ago. It’s a bustling place that attracts truckers, local white ranchers, tourists, and workers on the flower farms. Simpson told me that the shopping center was one of half a dozen innovations that Cholmondeley had brought to Soysambu. Another big improvement, he said, was his introduction of a pivot irrigation system, and he’d also encouraged his father to grow sweet baby corn, which the family now exports in large quantities toEurope, and to produce yogurt, one of Soysambu’s most popular products. “Tom is a progressive thinker,” Simpson told me. “He was always pushing to make the business more versatile.”

Despite these innovations, Soysambu has had a troubled recent history. Delamere Camp shut down in 2002, partly as a result ofthe wider, temporary collapse of the tourism industry in Kenya following the 9/11 terror attacks. The ranch is reportedly not robust, either. After ole Sisina’s death, Kenyan human-rights groups and other organizations called for a boycott of Delamere products, and revenues dropped by 50 percent between April and June 2005, according to The Daily Nation. Simon Cox insisted that the ranch is “profitable, but not easily profitable.”

I asked Simpson to comment on Cholmondeley’s behavior after his release from jail. One friend of Cholmondeley’s had told me that the Delamere heir had quickly picked up his life again. “If I had just shot a man dead, I’d disappear into a Buddhist monastery in Nepal, but not Tom,” he had told me. Another acquaintance said, “I met him at this party full of white Kenyans and he was completely the old Tom, well dressed, well spoken, abrasive, on the verge of arrogance. He said he was in touch every day with the Naivasha police, and he was happy with the way they were handling trespassers and poachers.” This acquaintance was struck by his seeming obliviousness to the animosity the killing had stirred up. “I said, ‘Don’t you think some people want your land?’ He acted like it had never crossed his mind. Finally, he said, ‘Oh, maybe I should look into that.’ He’s protected by all that money he has. He lives in a bubble; he’s a bit naive.”

Simpson insisted that, deep down, he is a generous and compassionate man. “Look, we wouldn’t be here in Kenya if we weren’t all eccentrics,” he said. “Everyone here is more flamboyant than the average person you’ll meet on the streets of London. But we’re all aware of our social responsibilities. I’ve sat here with Tom in this Indian restaurant, with black Kenyans, Indians, shooting the breeze, and he’s totally comfortable with them. He is a believer in Kenya.”

ON THE MORNING of Monday, September 25, at the sand-colored Kenyan High Court in downtown Nairobi, two dozen camouflaged soldiers leaped from the rear of a green truck and escorted Cholmondeley inside the building, along with dozens of other prisoners facing hearings that day. Dressed in a khaki linen suit and tie, Cholmondeley entered the courtroom in handcuffs and sat cross-legged on a scuffed wooden bench, blue socks protruding from brown leather boots. His face was expressionless; the only sign of stress was his hand clenched around one opened handcuff. His lean, towering father sat in the row just behind the lawyers; he was joined by Cholmondeley’s girlfriend, Dudmesh, and several friends. In the back row, arms folded on the edge of a wooden railing, sat Njoya’s widow, Serah.

A single judge, Muga Apondi, wearing a white powdered wig and red-and-black robes, listened to a half-dozen other cases before Cholmondeley’s. (In accordance with British jurisprudence, which Kenya’s legal system is based on, this judge will determine the defendant’s guilt or innocence, without using a jury.) Then Kenya’s director of public prosecution, Keriako Tobiko, declared, to a hushed courtroom, in both English and Swahili, “On the tenth of May 2006 at the Soy sambu farm… [Thomas Cholmondeley] murdered one Robert Njoya … We shall prove that the deceased was running away when shot by the accused. We shall also prove that in an attempt to conceal his crime . . . the accused tampered with the scene after shooting the deceased and two dogs. We shall prove the accused was not under any attack … We shall prove the accused attacked the deceased and his companions as a retaliation or revenge for trespassing or poaching on his land.”

For the next four days, the prosecutor and Cholmondeley’s defense attorneys grilled half a dozen witnesses. Peter Gichuhi Njuguna, 28, who was with Njoya when he was shot, testified that the men “were carrying the carcass [of an impala] to a nearby tree” when gunfire erupted without warning. “We heard a loud bang. The sound was coming from our right. When we heard the gunshots we started to run . . . We waited for a while, but we never saw [Njoya].” Carl Tundo said that, after relieving himself in the bush, he emerged to find Cholmondeley on one knee, aiming his high-powered rifle, firing four times with two-second intervals between each shot. “I was scared of whatever was in the bushes that Tom was shooting at . . . then I heard Tom shouting for me to run and get the car. ‘I have hit someone by mistake,’ he yelled,” Tundo said. He went on: “Tom was with the man tying his handkerchief around [Njoya’s] groin to try to stop the bleeding. He was talking to the man telling him to calm down.”

The court also heard testimony from Steven Koigi, farm manager at Soysambu, who painted a portrait of deteriorating security at the ranch in the months before Njoya was killed. “Many people have been shot at the farm, many times, and since February, managers have been robbed by unknown people,” he said. “The farm had witnessed several cases of poaching, theft of fencing wires, and illegal charcoal burning.” Then, after more back-and-forth testimony that seemed only to add to the murkiness surrounding the shooting, the trial was adjourned until October 30, and Cholmondeley was returned to prison.

ON MY LAST DAY in Kenya, I set out to visit Kamiti prison, in the hope of getting a glimpse of Cholmondeley. I drove down the busy Thika Road and, half an hour southeast of Nairobi, arrived at the prison, a low, sprawling complex in a weedy field surrounded by a ten-foot stone wall. I made it through the first checkpoint at the front gate, and a prison guard escorted me into the main administrative building, which stank of disinfectant. From the windows in the stairwell, I had a view of the grounds: a series of manicured grass courtyards, each one surrounded by tin-roofed, whitewashed one- and two-story buildings with narrow slits for windows. Hundreds of prisoners, all black, wearing loose-fitting white cotton tunics and white shorts, most of them serving long sentences for murder or rape or drug trafficking, milled around outdoors.

From friends who have visited Cholmondeley in prison, along with published reports, I’d already gotten a sense of how he spends his days. I’d been told that he was improving his knowledge of Kikuyu, Kenya’s main tribal language, playing badminton occasionally in the courtyard, and reading books, including A. Scott Berg’s Lindbergh and a collection of British classics. Once or twice a week he receives visitorshis parents, Dudmesh, close friendsin a crowded room, broken into cubicles, that reeks of body odor and urine. These encounters are limited to 15 minutes, and Cholmondeley and his fellow prisoners are separated from their visitors by three layers of chicken wire.

I waited for half an hour outside the warden’s office before I was ushered in. I could hear the singsong conversation, in Swahili, of prisoners gathered just below his window. I explained to the warden that I was interested in hearing about Cholmondeley’s life behind bars and, if possible, getting a meeting with him. He smiled, shook his head firmly, and told me I needed the permission of the director of prisons in Nairobi. “I can’t say anything more,” he told me, then he politely asked me to leave.

As the court proceedings creep forward, there has been much speculation about what the verdict might mean for Cholmondeleyand for Kenya. Many point to the lesson of Zimbabwe: Beginning six years ago, President Robert Mugabe addressed disparities of wealth and land in his country by forcibly expropriating 4,000 white-owned farms and handing them out to independence-war veterans, military officers, and ruling-party hacks, destroying Zimbabwe’s economy in the process. Some Kenyans believe that the Cholmondeley killings could play into the hands of opportunistic politicians who would like to see the Zimbabwe scenario unfold at home. Should Cholmondeley be convicted and sentenced to hang, the thinking goes, the rest of the familyand, indeed, Kenya’s tiny white landowning populationmight find life in Kenya so untenable that they’d opt to leave and sell their land at fire-sale prices. An acquittal, on the other hand, could create a different set of problems. Kenya is a country known for meting out brutal street justice to petty thieves and other minor criminals, and it is not an exaggeration to say that a man perceived by some as a killer would have to be extremely careful about his movements. He may well live in constant fear for his life. Whatever the verdict, the case has already sensitized many Kenyans as never before to the gross inequities between blacks and whites in the country. Observers believe that this is creating a seismic shift in Kenya, heightening resentments and leaving many whites with a deepened sense of insecurity. Either way, life in Happy Valley may be changed forever.

Earlier that week, when I’d talked to Hugh Simpson about his trips to see Cholmondeley in jail, he had insisted that his friend was upbeat about his prospects. “Tom knows that he didn’t go into this with malice aforethought,” he assured me. “He told me, ‘I’ll lose a lot of time and pay the price, but I didn’t do it intentionally, and the world will see it that way.’ “

His friends contend that the murder charge will be impossible to prove and that, at worst, Cholmondeley will be locked up for about a year while the case drags through the courts. But others aren’t so sanguine. “The defense counsel says he won’t get a fair trial. I completely agree,” Murgor, the former prosecutor, told me. “The whole background is too politicizedit’s become ‘the white man versus the black man.'” Journalist Parselelo Kantai believes that the version of the shooting presented by the surviving poachers will ultimately prove persuasive. “I think he will go down for this,” he said.

Nobody has been executed in Kenya since 1982, in the aftermath of a coup attempt against Moi, and it is highly unlikely that, if convicted, Cholmondeley will be sent to the gallows. But a life behind bars is a prospect that neither he, nor those closest to him, can bear to consider.

“Look, Tom is in a tricky position, but if he presents his case fairly, and honestly, I am certain he will prevail,” Simpson told me.

“Kenya is not a failed state, and Tom is going to get justice.”