Refugees in Chad

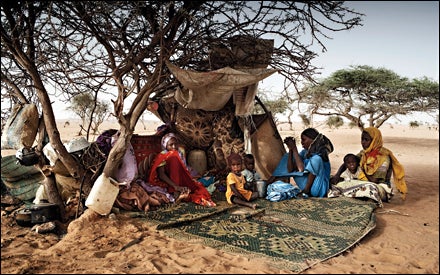

Newly arrived refugees wait outside the UN's Oure Cassoni camp, near Bahai, Chad

Newly arrived refugees wait outside the UN's Oure Cassoni camp, near Bahai, ChadChad, Sudan

School, Oure Cassoni Camp

Classes at Oure Cassoni

Classes at Oure CassoniJEM rebel soldiers

Young JEM rebel soldiers on the Chad side of the border

Young JEM rebel soldiers on the Chad side of the borderSchool, Oure Cassoni Camp

Sudanese refugees attend school in the nearby Oure Cassoni camp

Sudanese refugees attend school in the nearby Oure Cassoni campBahai Mosque

Muslims in Bahai gather around the settlement's biggest mosque

Muslims in Bahai gather around the settlement's biggest mosque╠ř

The road to hell begins in N'djamena, a Third World backwater that seems to cram all of Africa's problems corruption, neglect, war, stagnation, tribal rivalry, disease into a few dusty, desperate square miles. The temperature pushed 120 on a June afternoon as photographer Marco Di Lauro and I weaved through the streets of Chad's capital, following Idriss, a jellabiya-clad rebel from the Justice and Equality Movement, the biggest of at least half a dozen factions waging war with government forces across the border in the Sudanese province of Darfur.

We were on our way to an interview with JEM's head of intelligence, who happened to be in town that week. After leaving the Pekin Hotel, our Chinese-run bed-and-breakfast, we skirted the Chari River, a murky stream populated by hippopotami and by smugglers who wade across the shallow water from neighboring Cameroon, delivering electronics and other goods to far more impoverished Chad. Blocks from the river, red-bereted members of the Presidential Guard patrolled grim-faced in front of the concrete Palais Rose, the official residence of unofficial president-for-life Idriss D├ęby Itno. Next to the palace stood Chad's national museum, scarred by a February 2008 rebel attack that left gaping holes in the roof and the bones of an elephant visible through a perforated wall. Vendors loitered on sidewalks in front of pastel-painted, arched colonial buildings, hawking Viagra, fake Swiss Army knives, and Celtel mobile-phone cards. This forlorn center of N'Djamena's commercial life consisted of two banks, a French bakery, the Air France and Ethiopian Airlines ticket offices, and a handful of expat-friendly restaurants.

N'Djamena was never going to be one of the great capitals of the world; its location in the heart of Africa's bleakest, most resource-starved region guaranteed that. But the place has fallen upon especially hard times of late, thanks largely to its neighbor, Sudan. The intractable war that has dragged on since 2003 in the Darfur region, pitting rebels against the Islamist government of indicted war criminal President Omar al-Bashir, has deepened Chad's isolation and instability. It has stirred up an indigenous Chadian rebel movement, plunged much of the country into lawlessness, and made life increasingly difficult for the thousands of international aid workers who've descended on the area to try to help Darfur's refugees.

╠ř

That's what drew Marco and me to Chad in the first place: to see if the biggest aid effort since the Rwandan genocide of 1994 is accomplishing anything. The roughly 2.7 million “internally displaced” within Darfur are scattered among more than 100 camps staffed largely by Sudanese workers, and access to them is difficult because of the ongoing conflict and the Sudanese government's hostility toward the West. But some 330,000 refugees have spilled into Chad, and much of the international aid effort is concentrated in 13 camps strung along its eastern border. Chad has been almost totally subsumed into its neighbor's chaos; it's been pulled so far into Darfur, it has almost become Darfur. We wanted to see what happens to a country already rife with instability when it gets plunged into a conflict that the rest of the world would rather ignore.

N'Djamena is the gateway to the Darfur madness, an alternate universe where power cuts can last six hours a day. A drive through the capital at night feels like a trip through the pre-industrial age, the pitch black of the streets broken only by the occasional glow of a battery-powered shop light. ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° of town, the roads are filled with bandits. Moving around by air can be an even bigger challenge. Last spring, all domestic flights were canceled for days the country's jet fuel had been, as the capital rumor mill had it, handed over to the air force to bomb Chadian rebel bases inside Sudan. In my first five days in N'Djamena, a sandstorm blew in, followed by a torrent of muddy hail, paralyzing the city for hours; my attempt to get a government travel permit was delayed “indefinitely” because the functionary responsible had been stung by a scorpion; and I contracted a wretched sinus infection that forced me to wander the streets at midnight looking for a Western medical clinic. Celeste Hicks, a BBC reporter who's lived in N'Djamena for nearly a year, calls it “the worst place I have ever experienced.”

Still, the relief workers keep coming. Never mind that the work is dangerous and often seems futile. Never mind that the camps function as recruiting grounds for the rebels and may be creating a dependency among the refugees that will be hard to break. For many, Chad offers the biggest adventure in aid work: the allure of danger, the satisfaction of restoring broken lives, and the end-of-the-world beauty of red sand, swaying acacias, and infinite skies. “It's a constant rush,” said one veteran aid worker, an Italian stationed in the eastern-Chad outpost of Ab├ęch├ę, one of the hubs of the relief effort.

That's where Marco and I were headed. The rebel intelligence chief we met through Idriss told us that traveling inside Darfur with JEM was impossible too dangerous, too open-ended. Instead, six days after our arrival in Chad, we stood at the check-in counter for the early-morning World Food Program flight to Ab├ęch├ę. In front of us was a rugged, red-bearded water engineer named Erik, who worked for the Swedish government in partnership with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Erik was in his mid-forties, an aid veteran with a fondness for dispensing wisdom about surviving in one of the most exasperating countries on the continent.

“Murphy's Law is the only law in Chad,” Erik said, nudging his duffel bag toward the front of the line. He was traveling with another Swede, Liv, a 32-year-old who'd left her job as a consultant in Stockholm to come dig bore-holes in the UNHCR camps. She cited a failed relationship, boredom with comfortable Scandinavian life, and “the desire to do something good in the world” as the motivations for taking a yearlong contract with the UN. Liv had arrived the previous evening. It was her first trip to Africa.

Moments later, the World Food Program manager in charge of the flight delivered bad news: Fuel supplies in Chad had been “contaminated,” and all flights were grounded. This was a regular occurrence, Erik said; corrupt officials often mix locally refined fuel with water, turning a profit by selling off the diluted product.

“It could be a week,” Erik said as the four of us piled into a battered taxi headed back to the hotel. “Here, you don't just need a plan; you need a backup plan to your backup plan.”

N'DJAMENA IS BAD enough, but there's always fresh chaos awaiting the relief workers in the desert. Back in February, Oxfam estimated that every month 25 attacks occur on NGOs operating in eastern Chad. The most alarming happened in May 2008, when Pascal Marlinge, a 49-year-old French humanitarian aid worker for Save the Children UK, was executed with a pistol shot to the head. In March, bandits seized three workers from Doctors Without Borders and held them for several days. The 5,000-man UN security force promised last year to stabilize the border has deployed just 2,800 men and can't stop the rising violence. “It's total impunity out there,” says M├ąns Nyberg, a UNHCR official in N'Djamena.

Even before war erupted in Sudan, the former French colony of Chad was hardly an island of stability. Since its independence, in 1960, the country has been ruled by a string of dictators, buffeted by coups, rebel invasions, and meddling from foreign powers like Libya, which briefly annexed Chad in the eighties. President D├ęby, a former military officer and a Zaghawa tribesman, came to power in 1990 after leading a guerrilla army across the Sahara and, with Libya's help, ousting dictator Hiss├Ęne Habr├ę. The first ten years of D├ęby's tenure were relatively stable; the country began pumping crude from around Lake Chad in 2003 and now earns more than $1 billion a year in oil revenues. But the war in Darfur sent everything south.

Most of us know the basics of that conflict: the Arab militias-on-horseback known as the janjaweed, the allegations of genocide, the parade of celebrities George Clooney and Don Cheadle and Ange┬şlina Jolie visiting the refugee camps and condemning the systematic rapes and killings. But many people tuned out long ago, bewildered by the conflict's political complexities, its remoteness, its seeming intractability.

So here's the compressed version: Darfur is a Texas-size province of six and a half million Sudanese, virtually all of them Muslim, spread over an advancing desert with a few ribbons of green. The region has long been afflicted with a scarcity of resources, an easy flow of weapons, and a combustible mix of Arab and African ethnic groups. But it began to spiral downward in the eighties, when Arab nomads in the north pushed south as a result of diminishing grazing land. The conflict was stirred up by the 1989 military coup in Sudan that brought then-General al-Bashir's National Islamic Front to power, transporting Arab-supremacist doctrine to the restive province.

Then, in early 2003, an African rebel group, the Sudan Liberation Army, launched attacks on army garrisons, calling for a greater share of resources and local autonomy. Al-Bashir turned to the police, the army, and the janjaweed militias to suppress the rebellion. One year later, janjaweed leader Musa Hilal issued a directive to “change the demography of Darfur and empty it of African tribes,” which he and the Sudanese army have carried out with terrifying efficiency. Estimates on the number of dead range from 200,000 to 400,000 if you count starvation and disease. Close to three million people have lost their homes.

Meanwhile, the conflict bleeds back and forth across a 700-mile-long open fron┬ştier. Sudanese rebels many from D├ęby's tribe, the Zaghawa have used Chad's eastern desert as a base from which to launch attacks inside Darfur. Chadian rebel groups have also gotten into the game. Al-Bashir has been giving money and weapons to an anti┬şgovernment coalition led by D├ęby's own nephew, who is said to be angry about his uncle's hoarding of oil revenue. Indeed, the increasingly paranoid and reclusive D├ęby has used almost all of the oil money to buy arms to fight these Chadian rebels.

The West has been sounding the alarm about Darfur for years, but nobody has any clear idea how to end the conflict. In 2004, Congress voted to label the war a genocide, despite the UN's hesitancy to do so. Journalists like New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof have reported tirelessly on the atrocities, and the coalition Save Darfur has staged protests. The Bush administration toughened the sanctions that President Clinton had imposed on al-Bashir's regime and backed the creation of an African Union peacekeeping force. But the ill-equipped African peacekeepers could not protect Darfur's civilians, and in early 2008 an expanded UN force was sent in, also to little avail.

The war took a new turn in May 2008, with the rebels' boldest assault yet: Operation Long Arm, in which hundreds of JEM soldiers drove four days across the desert to surprise Sudanese forces in Khartoum, the capital, and the city of Omdurman. The al-Bashir government, blaming D├ęby, severed relations with Chad immediately. Sudan's relations with the West have deteriorated as well: In March, the U.S. supported the International Criminal Court's indictment of al-Bashir for war crimes; in response, he kicked 13 international aid agencies out of Darfur and vowed that he would never surrender, making him a hero to some in the radical-Islamist world.

So far, the West's only option has been to minister to the refugees, hoping to maintain some semblance of civilization in the barbarous desert. The do-gooders have arrived with food, water, and medicine. Some have come armed with expertise in engineering, construction, and education and some with only their good intentions.

In the latter group are people like Linda, a 32-year-old French Canadian of Egyptian descent, who was on her way to work for Chad Solaire, a Dutch NGO trying to introduce “solar cookers” strips of aluminum foil glued to pieces of cardboard to refugee women along the border. The idea is to wean them off collecting firewood, a practice that has been devastating the fragile semi-desert and causing violent confrontations between refugees and locals. Linda had been inspired by a documentary about aid workers in Africa and had volunteered to live in Bahai, the most desolate UN outpost in the most dangerous corner of northeastern Chad.

“You should come out and visit,” she told Marco and me as we dined together in N'Djamena one sweltering evening. It was an offer we found impossible to resist.

“BIENVENUE ├Ç BAHAI,” said the sous-pr├ęfet, a wizened man with a white goatee, who reclined on a foam-rubber pillow at the decrepit district headquarters. ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°, the red-blue-and-yellow flag of Chad flapped madly in a gathering sandstorm, and the acacia trees in the nearby wadi, the dry riverbed marking the border between Chad and Sudan, bent low in the gusts. Robed figures drifted like ghosts through a maze of mud-walled compounds, past a blue concrete mosque and a forlorn market selling desiccated dates. The sous-pr├ęfet put on his spectacles and perused our accreditation papers.

“Vous ├¬tes Americains?” he asked.

“Oui,” I said.

With a flourish, he stamped the papers and handed them back to us. “Barack Obama, il est magnifique,” he said. “When you go home, give our regards to Number 44.”

The UN compound was at the edge of the seminomadic settlement: a football-field-size encampment surrounded by a concrete wall and razor wire. A dozen security guards stood around the metal gate, huddled together trying to light cigarettes in the wind. A Chadian UN functionary escorted us across the courtyard to our guest quarters. I turned the key in the flimsy lock on one of the bedrooms and pushed open the door. Cockroaches big, brown, armored skittered across the floor.

“For Christ's sake!” I exclaimed, squashing two with a boot. The guest quarters' chef came running from the kitchen next door.

He shrugged. “Mais, c'est normale.”

As remote as Bahai was, the settlement was just the beginning of our journey. Oure Cassoni, the most remote refugee camp along the Sudanese border, lay 18 miles farther north along a sand track that passed through the heart of bandit territory. Oure Cassoni had come into being in the spring of 2004, at the height of the janjaweed killing spree, after 28,000 refugees from around the market town of Kutum fled into Chad en masse.

Relief officials moved them into a temporary location near a saline lake, then set up administrative headquarters here in Bahai, which was deemed to be somewhat safer for aid workers. (Indeed, 12 days before we arrived, a Sudanese Antonov bomber searching for rebels had dropped its payload just outside Oure Cassoni, killing several Chadian shepherds and hundreds of their animals.) The majority of staff in the camps are local hires; in fact, there were only about 15 international aid workers living in Bahai, from the International Rescue Committee, UNHCR, Doctors Without Borders, and a few smaller NGOs. All the relief workers commuted to the camp five days a week a trip of about 45 minutes in a convoy guarded by Chadian and UN police.

The relief convoys weren't running on the weekends, however. So, the morning after our arrival, a Saturday, Marco and I rented a Toyota Land Cruiser for $200 a day and hired a local translator, Mahmadou, and a driver, Ali. Ali kept his fists clenched around the steering wheel, Sudanese music blaring from the cassette deck, bouncing down rutted tracks at 40 miles per hour. An hour later, we were walking through the sandy warrens of Oure Cassoni's Zone C, one of the camp's three divisions. Originally a sea of tents, the place now had an air of permanence, with solidly built, mud-walled residential compounds; a network of canals and pipes to bring water from the distant lake; UNICEF elementary schools; medical clinics; gas stations and auto-repair shops; and a vast bazaar selling used clothing from the U.S., biscuits from Nigeria, and orange drinks from Jordan. The inhabitants appeared to be far better off than the indigenous Chadian population, a fact that has caused tensions between refugees and locals.

In some ways, Oure Cassoni mirrored the larger conflict. The inhabitants of zones A and C stood behind the Justice and Equality Movement; Zone B's population, from central Darfur, supported the Sudan Liberation Army, which signed a peace deal with the al-Bashir regime in 2006. The factions generally steered clear of each other, but sometimes clashes broke out and UN officials were forced to intervene.

Abu Jabbar, the leader of Zone C, a gaunt, imposing man who speaks English and has played host to virtually every visiting celebrity, greeted us outside his compound. Despite the primitive surroundings, Jabbar kept on top of world events via the BBC and occasional articles that his journalist friends sent him. “Do you know Samantha Power?” he asked as we sat in his courtyard, sheltered from a strengthening wind, eating from a communal tray of sorghum and gravy, sweet macaroni and rice. “She is now working for Obama, we have heard.”

When we left the camp after lunch, the wind had intensified into a raging sandstorm, and I could just make out figures camped underneath a withered acacia tree. Marco, Mahmadou, and I left the car and walked toward them. Six small children, their faces smeared with sand, grit, and mucus, were hunched against the howling wind, crying as sand flew in their faces. Four jerry cans of water and two cooking pots lay on the ground; plastic bags filled with clothing swung from the branches.

“We've been out here for 15 days,” said one of the mothers. They'd fled a Sudanese-army bombing raid on a village in southern Darfur, she claimed, and walked for six days to Oure Cassoni. Now they were stranded, unable to settle in the camp because they hadn't been interviewed yet by the UNHCR team and given ration cards. “They sent people to talk to us last week,” she said, “but they haven't come back.” Refugees inside the camp were allowing them to draw water and giving them food. There were hundreds of others nearby, all hunkered down in the driving sand.

“My God,” said Marco, “there are people under every tree.”

Frederic Cussigh, the worn-down Frenchman who headed the UNHCR field office in Bahai, later told us that long waits were customary for newcomers; the “refugees” could in fact be Chadian locals willing to put up with weeks in the brutal sun for the chance to take advantage of the camp's free food, shelter, and medical care. But one UNICEF official I later met in Ab├ęch├ę sharply criticized the UN screenings: Even if some of the people were Chadians posing as Darfurians, the official said, the UN's treatment was heartless. “By the accident of being born on the wrong side of a wadi [in Chad], these people get none of the benefits. Yet their lives are every bit as fragile.”

It was impossible to tell what the truth was.

UNDER A CANOPY OF STARS, at the UN compound in Bahai, two American women in their twenties, unwashed hair tucked haphazardly beneath headscarves, sat with their laptops at a rickety table in a courtyard, smoking and catching up on e-mail. Both worked for the International Rescue Committee. “This is what passes for social life in Bahai,” one of them told me. There was also a bar patronized by both Westerners and locals a handful of stools under a straw roof, with warm beer and Sudanese music but it was hard to find one's way there in the darkness.

Cussigh, the UNHCR director, passed by a moment later; he'd been working late in his office. I asked him whether it was true, as had been frequently reported, that the Justice and Equality Movement has been recruiting child soldiers inside the camps. Although JEM and civilian refugees have always denied the allegations, one UNHCR official in N'Djamena told me that “there's absolutely no question” that the camps have become militarized. Last May, Sudanese government forces in Khartoum took 89 alleged child soldiers into custody in the wake of JEM's Operation Long Arm, and soon after, a London-based human-rights group, Waging Peace, charged that refugees as young as nine were being sold to JEM.

Cussigh shrugged. “We're not in the camps much of the time,” he replied, “so what happens when we're gone is hard to say.” I'd obviously touched a nerve, and the UN later insisted that field staff are in the camps every day. But it's a thorny issue. One aid official in N'Djamena told me that the camps are in some ways fueling the conflict, by serving as a kind of “one-stop shopping mall” for Darfur rebels. Here, JEM and other factions can repair their vehicles, rest up, and find a supply of well-nourished, ideologically primed young recruits. The UNHCR has been powerless to confront the armed men.

Some critics of the relief system argue that the camps are helping to sustain the conflict in less tangible ways. They make it more difficult to find a long-term solution, giving world leaders an excuse to avoid the hard business of negotiating for peace, applying “humanitarian Band-Aids to gaping human-rights wounds,” as actor Don Cheadle and aid expert John Prendergast wrote in The Wall Street Journal in 2005.

Emergency aid has also become, in effect, big business. Caring for 330,000 destitute refugees in Chad not to mention the millions displaced inside Darfur requires outlays of more than a billion dollars a year. “So many livelihoods UN agencies, NGOs, private companies, relief workers, contractors depend on the conflict,” says Clare Lockhart, founder of the Institute for State Effectiveness, which promotes strengthening local institutions as an alternative to long-term relief. “Individuals may have the best possible motives, and they're performing dangerous, important work, but one of the unintended consequences is creating a whole set of actors who need the situation to continue.”

In a place like Darfur, where fear and violence have caused huge population displacements, long-term emergency relief may be unavoidable. Still, says Lockhart, it's essential to have an exit strategy. “You have to make the right judgment call about when the moment is right for resettlement,” she says. “In Afghanistan, an early rush to send people back so quickly put stress on the situation.” When the time does come, she said, foreigners should fade from the picture and empower local communities improving courts, training anticorruption units, setting up self-sustaining business enterprises. “In places like southern Sudan or Afghanistan, the key issue is building up the country's capability to sustain itself,” Lockhart says.

But knowing when a country can stand on its own is tricky. In October the Obama administration, already knee-deep in Afghan┬şistan, announced a new policy toward Darfur. After months of stark divisions about how to approach the al-Bashir government, the administration decided on a strategy of “incentives and pressure” aimed at nudging him toward a permanent peace deal with the rebels. The new moderate course reflects the views of Obama's special envoy, Major General Scott Gration, a former Air Force officer who grew up in East Africa. While some in the administration have stuck to the line that Darfur is an ongoing genocide, Gration has argued all along that the situation is more accurately the “remnants” of genocide and has commended al-Bashir for allowing some of the expelled aid groups back into Darfur. “We see that there is a spirit of cooperation and an attitude of wanting to help,” he recently said.

The Sudanese government has welcomed the new approach. Gration is “creating a healthy environment, rather than poisoning it,” said Sudan's state minister for foreign affairs, Samani Wasila, “which will lead us to a place where people can sit and talk.”

This kind of language is encouraging. And some observers, including the departing commander of the UN peacekeeping force, have pointed to a drop-off in violence over the past year (a sharp fall in combat deaths, fewer attacks by the janjaweed) as a sign of progress. Others cynics or realists, take your pick say the reason for that is simple: The refugee camps have drawn off most of Darfur's population, leaving fewer villages to destroy. Edmond Mulet, the assistant UN secretary-general for peacekeeping, pointed out that, though the level of fighting has diminished, 140,000 people sought refuge in camps in both Darfur and Chad from January to May.

As he told The New York Times in July, “it is still far from peaceful.”

LATER THAT AFTERNOON, we hopped in the truck and sped down a wide sand track along the Sudan border, with Zone C leader Jabbar in the backseat. Lone acacias, standing like sentries amid a sea of reddish sand, swayed in the haze. Jabbar held my Thuraya sat phone out the window, searching for a signal. “They're supposed to meet us around this place,” he said.

Marco and I had been trying to connect with the rebels in the field, to get a bead on where the conflict actually stood. They'd turned out to be a surprisingly accommodating and media-savvy group. JEM's London-based representative had unfailingly answered my e-mails and put me in touch with Idriss in N'Djamena. Thanks to a morning satellite call from Jabbar to his JEM contacts inside Darfur, a group of fighters were now driving 70 miles from their Darfur base for a mid-desert press conference.

Suddenly, a Toyota pickup emerged out of the haze and roared alongside us. Eight JEM rebels in desert camouflage stood in the bed, draped in bandoliers and carrying Kalashnikov rifles. A 50-caliber machine gun was mounted on the truck, and a dozen grenade launchers hung from the side. We pulled over and the rebels a couple of them teenagers leapt to the ground. Handshakes all around.

“Salaam aleikum,” said the commander, a slim, goateed man wearing a green turban. In halting English, he introduced himself as Arku Tugud, the deputy head of JEM intelligence. Tugud looked at the road nervously, then at the sky. “Not a good place for us to stay,” he said. “They can spot us too easily.”

We veered off the main road and parked in a grove of thorn bushes. Tugud sat cross-legged in the sand. It was he, he made it clear, who would begin the questioning. Tugud wasn't comfortable in English, so Jabbar translated.

“What is ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° magazine?” he asked. “How many readers do you have?”

I explained a bit. He nodded. “And do you have a business card?”

“Business card?” I asked, incredulous. Tugud nodded again and waited expectantly. “Regrettably, I haven't carried mine with me,” I said.

Tugud looked annoyed. “No cards?”

Marco stepped up and handed him his own card. “I can vouch for him,” he said.

Tugud seemed to relax and began to talk. The group's momentum was unstoppable, he insisted. “JEM surprised everybody when they went all the way to Khartoum, across the desert,” he said, “and showed they could fight not only in Darfur but in the heartland of the Sudan government.” Operation Long Arm, Tugud said, with some exaggeration, “caused an effect in all the world. As you know, JEM was very small before, but afterward everybody knew that JEM was good in its objective, and all the groups of the rebels are joining JEM, and as a result it is becoming strong.”

How much support was the D├ęby regime giving JEM? Weapons? Money?

He smiled and answered cagily. “The Chad government doesn't want us here. We cross the border without permission, and the police often chase us back.”

I asked Tugud whether he saw signs of progress at the negotiating table. I'd heard that recent talks in Doha, the capital of Qatar, had gone nowhere. Tugud agreed but put the blame on the government. “We came with proposals a month ago to Qatar,” he said. “If Bashir moved forward on this, it would be a sign of good faith. We wanted him to stop the bombing by the Antonovs, stop the attacks of the janjaweed. But nothing has changed.” According to one U.S. diplomatic source I talked with, however, the fault lay equally with JEM, whose leaders had made concessions and then rescinded them.

As our interview drew to a close, we heard a humming high above our heads. Looking up, we could see a large white airplane moving slowly across the clearing sky.

“Antonov,” said Tugud.

“Can they see us?” asked Marco.

“It is possible,” he replied. “They can for sure see our vehicles.”

Nobody moved. The rebels' eyes tracked the plane as it headed southeast, in the direction of Sudan. Everyone knew that if the pilots decided to drop their bombs, we'd have nowhere to take cover.

And then it was gone. Tugud, relieved, stood up and shook hands. He gave us his sat-phone number and told us we were welcome to rendezvous with him in Darfur anytime. The commander and his rebel band climbed back into their truck. “In Darfur, you know, the Antonovs search for us every day,” Tugud said. Then he sped off in a cloud of dust.

FOR ALL OF THE JEM fighter's confidence, the rebels and the Sudanese government appear locked in a standoff a low-level conflict that could drag on for years. And in a region with scant resources and deep-seated tribal rivalries, negotiations and politics sometimes only just scratch the surface. To some experts, the war in Darfur is really about a destitute, hungry population trapped in a dog-eat-dog competition for diminishing land and sustenance. In a world of global warming and advancing deserts, of growing populations and shrinking food supplies, lasting solutions become less and less possible. The U.S. military has predicted that global warming will intensify food shortages and water crises all over the world, nowhere worse than in sub-Saharan Africa, which could see far less rainfall and a rise in median temperature of up to nine degrees Fahrenheit by 2050.

Indeed, it's tempting to give up entirely on this sinkhole, to write the whole region off as an unmitigated, unsolvable disaster. Driving the dusty streets of N'Djamena, with Chad's rapacious president sealed inside his palace while his citizens swelter in their electricityless shacks, interviewing stranded Darfurian refugees (or Chadian imposters) huddled in a sandstorm, I sometimes felt overwhelmed by hopelessness.

But I also spoke to several experts in nation building who aren't so downhearted. In 2001, Clare Lockhart set up a series of institution-building projects, including the National Solidarity Program, which provided grants of between $20,000 and $60,000 to 23,000 Afghan villages. The program eliminated foreign NGOs and their overhead costs, placed the cash in village trust funds, and required the establishment of democratic councils to determine how the money would be spent. “The villagers own the solutions,” Lockhart says. “They're the ones doing the labor.”

Yet for all of the project's success, it is surrounded by failures of a huge scale. Over the past three years, the Taliban has extended its control over large swaths of Afghanistan. The government is corrupt and inefficient, and the country has become so dangerous that most of the several thousand foreign aid workers in the country can't travel outside Kabul. Clearly, in terms of turning these wrecked countries into functioning nations, we have a long way to go.

Until that happens, it will be left to the army of international relief workers dedicated, courageous, sometimes naive to apply their “humanitarian Band-Aids.” On our last day in Bahai, Marco and I found Linda, the aid worker from Quebec, in the earthen compound she shared with a Chadian colleague. Delighted to see us, she led us into a tiny asphalt courtyard, to a rickety table on the veranda outside her bare room. Nibbling on soft licorice candies she'd brought from home, Linda produced a Chad Solaire cooker and propped up the flimsy aluminum-foil-and-cardboard contraption in the searingly hot courtyard. She had spent the past four days taking her devices through Oure Cassoni, giving demonstrations to skeptical Darfurian women. “Of course, it's not as efficient as firewood,” she admitted, wrapping a plastic bag around a black metal pot and sticking it beneath the jury-rigged solar panels. Linda said it took two hours to cook a pot of rice and three hours to boil a piece of meat, and the device had to be rotated constantly as the sun moved across the sky. “The idea is to turn cooking into a social event,” she explained.

There was something both infectious and poignant about Linda's enthusiasm. Earlier we had asked Abu Jabbar whether the refugees would accept the solar cookers, and he'd shaken his head. “Maybe to heat a pot of tea,” he said, “but that is all. She is just wasting her time.” For Linda, through, the refugees' recalcitrance seemed beside the point; in this blasted desert at the end of the earth, where rebels roam and Antonovs drop bombs from cobalt skies, she'd found a sense of purpose.

We left Linda standing at the entrance to her compound, a fragile figure with an expression that radiated joy, squinting into the harsh sunlight. “I really couldn't imagine being anywhere else,” she said.