It was late afternoon by the time we got out of the forest. The lush meadows at the bottom of Kenya’s Orng’Arua Valley were awash in yellow light. Liz put the Pajero in low to ford a small river; once past it, we followed an old jeep track that snaked through the flats toward higher ground. We were halfway across before we noticed the water glinting between the tussocks. “Keep it rolling,” I yelled, but too late. The four-wheeler lurched forward, shuddered, and then, wheels spinning, settled slowly into the muck.

Mike Saitoti Ole Tiampati, second from left, with a band of Loita Hills Masai

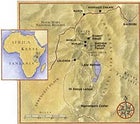

Mike Saitoti Ole Tiampati, second from left, with a band of Loita Hills Masai African Arcadia: The remote Loita Hills, a stonghold of Masai pastoralism that faces privatization and development

African Arcadia: The remote Loita Hills, a stonghold of Masai pastoralism that faces privatization and development Newly circumcised boys and girls, identified by their painted faces

Newly circumcised boys and girls, identified by their painted faces The author jacks up the bogged Pajero

The author jacks up the bogged Pajero

Zebras browse north of the Serengeti

Zebras browse north of the Serengeti Mokope

Mokope A boy herding cattle in the Loita Hills

A boy herding cattle in the Loita Hills Rim shot: Mike , and Lulunken gaze intoTanzania’s Ngorongoro crater

Rim shot: Mike , and Lulunken gaze intoTanzania’s Ngorongoro crater

I swore, Liz banged the steering wheel, and the two Masai in the backseat, Mokope and Lulunken, softly cluckedtheir tongues in dismay. Mike alone seemed unperturbed, merely raising his eyebrows.

“Ah,” his expression seemed to say. “An adventure!”

The five of us stepped gingerly onto the spongy grass. It was nearly dusk. We had no winch, and our one shovel was three miles away in camp, leaning against a tree. The prospect of a foodless, blanketless night out here was distinctly unappealing. Then again, so was the idea of walking home. That morning, a few miles downvalley, seven lions had attacked a herd of cattle just outside a Masai homestead. They’d only killed one young bull before a group of moran—young, toga-clad warriors—chased them off, but it seemed reasonable to assume they were still prowling the area, and still hungry.

Lulunken cinched a red plaid shawl around his shoulders and bent down to peer beneath the vehicle. Mokope squatted next to him, pointing with his orinka—a lethal-looking billy club carved from an olive branch. From their sober tone I gathered they were devising some sensible plan of action. Mike listened for a moment, then began sputtering with laughter.

“What’s so funny?” Liz asked.

“They are saying, ‘It’s strange—the stomach has been caught by the ground.’ ”

Liz rolled her eyes, and Mike laughed. “It’s something that always amazes me about the Masai,” he said. “They know their animals so well. If something goes wrong with a cow or a sheep, they can fix it. But when it comes to cars, they are useless.”

Coming from someone else—a white Kenyan, say—the observation might have sounded condescending, or worse. Mike could get away with it because he was a Masai himself. True, he’d lived in Nairobi half his life and grown comfortable with the ways of the world. Now, perhaps, he was just another cool Kenyan in jeans and a Tusker beer polo shirt, a city slicker having fun at the expense of his country cousins. But behind the laughter there was something else: a kind of pride, or even a subversive delight, in his tribe’s reluctance to embrace the modern world.

“Guys, it’s getting dark,” Liz said. “Do either of you have any thoughts on what we ought to do?”

We didn’t, really, but Mokope and Lulunken did. Tossing their heads in the direction of camp, they shouldered Liz’s camera gear and began picking their way out of the bog.

Mike grinned. “I think we had better start walking,” he said.

NO ONE IS CERTAIN WHEN the Masai first appeared on the high steppes of East Africa, or where they came from. Taller and fiercer than the more numerous Kikuyu and other Bantu-speaking peoples that surrounded them, and contemptuous of their neighbors’ agrarian ways, they roamed the landscape in nomadic bands, driving their livestock before them, running down lions with spears, and subsisting almost exclusively on blood and milk. By the mid-19th century, when the first European explorers arrived, the Masai controlled a major part of what is now southern Kenya and northern Tanzania, from Mount Kenya in the north to well beyond Mount Kilimanjaro and Ngorongoro Crater in the south.

When a 29-year-old Scot named Joseph Thomson proposed to cross Masailand, in 1882, the American explorer Henry Morton Stanley advised him to take a thousand men “or write your will.” Thomson took 143, but made it from Mombasa to Lake Victoria and back, the first white man to do so, and the first of many to become smitten with the Masai. “I could not but involuntarily exclaim, ‘What splendid fellows!'” he wrote of his initial encounter with a band of warriors. They had “an aristocratic savage dignity that filled me with admiration.”

Masai spears were no match for European guns, of course. But even as the British who colonized Kenya drove the Masai from some two-thirds of their land in the first two decades of the 20th century, they retained a lingering affection for the proud pastoralists. “Maasai-itis,” as one British writer termed it, has stricken generations of visitors.

My girlfriend and I, however, were not among them—or so we thought when we flew to Kenya on a spur-of-the-moment vacation two years ago. Our plan was to spend a couple of weeks lounging on the beach near Mombasa. When we met an American photographer named Elizabeth Gilbert there, and she mentioned that she was compiling a photographic record of traditional Masai culture, both of us wondered why—hadn’t everyone done a coffee-table book on the Masai? Our cynicism evaporated when Liz invited us to join her on a four-day shoot on the west side of the Great Rift Valley, the massive, volcano-strewn trench that runs through the heart of East Africa. We caught the next train to Nairobi.

Liz’s translator and photo assistant on that trip was a handsome, articulate 27-year-old Masai named Michael Saitoti Ole Tiampati. Born in the hills above Lake Naivasha, Mike had tended the family herds until age 12, when he’d won a place at a prestigious Nairobi boarding schoola rare achievement for a Masai. Since then he’d worked in journalism, first as aninterpreter and assistant producer at the Reuters Nairobi bureau, and later as an underpaid reporter for a magazine called Nomadic News. He’d been pretty much everywhere in Kenyan Masailand, with one exception. One day, we scrambled to the top of a granite outcropping and he pointed to a distant blue range down on the Tanzanian border: the Loita Hills.

“That’s the place I want to go,” Mike said. “That’s where the pure Masai live.”

Actually, until the British came, the Masai had largely steered clear of the Loitas. It was a place known for disease—cattle didn’t last long there—and for witchcraft. But a century ago, after being dispossessed of the so-called White Highlands of the Laikipia Plateau and driven south across the Great Rift Valley, a few renegade clans had settled the hills. The roads were supposed to be terrible, Mike said, some of the worst in the country. But a famous

laibon

, or holy man, lived in the Loitas, a direct descendant of Mbatian, the legendary Masai leader who in the late 1860s had foretold the coming of the “iron snake”—the British railroad—and the subsequent downfall of his people. There was a sacred forest, too—the Naimina Enkiyio, or Forest of the Lost Child, perhaps the biggest chunk of primeval wilderness left in southern Kenya.

The Loitas were also the setting for a troubling land dispute. In 1993, Mike said, the Narok County Council, the reigning political authority in western Masailand, abruptly designated the forest a game reserve and announced plans to develop it as a tourist destination. A fierce battle had raged ever since. The Loita Masai were stubborn, and not about to relinquish control of their forest to anyone, even other Masai. The inevitable result, they argued, would be another park like Tanzania’s Ngorongoro Crater—a beautiful corner of Masailand where the Masai themselves were no longer welcome.

It was a small fracas, perhaps, but emblematic of a phenomenon infecting all of Masailand. Acreage there has traditionally been “owned” collectively. But since Kenya’s independence in 1963, non-Masai farmers have steadily chipped away at its edges, and water and good pastureland have become ever scarcer. Even the Masai themselves have begun to take individual ownership of plots for farming and grazing, particularly in eastern Masailand, close to Nairobi. Every year more and more land is broken up into titled parcels—the kiss of death for a nomadic people.

That one glimpse of the Loitas stayed with me long after I left Kenya. The idea of a verdant African Arcadia shimmering out there in the desert haze was tantalizing. But Mike’s quest also intrigued me. What were the Loitas for him? Were they merely a journalistic opportunity? Or was there something else out there he hoped to find?

ALL GOOD ROAD TRIPS START GIDDILY, and our safari was no exception. We ran through Nakumatt, Kenya’s Wal-Mart, stuffing jumbo shopping carts with cookware and jerricans. An hour later we were on the dual carriageway—the freeway— speeding out of Nairobi. Our destination was the west side of the Great Rift Valley, more remote and less developed than eastern Masailand, and the place where Mike grew up. KISS 98 FM was playing a Tupac Shakur song on the radio, and he leaned forward to turn it up.

“Last time I was here, you were listening to Kenny G,” I said.

“Tupac’s a west-side guy, man,” Mike replied. “Like Snoop.” He tapped his L.A. Lakers cap. “I like the west side.”

Musical tastes notwithstanding, Mike seemed pretty much the same guy I remembered. He was witty, eloquent, and outwardly relaxed. Indeed, he seemed to have an aristocratic calmness about him, as if he came from wealth and nothing could really faze him.

But I got the sense that inside, something had started to gnaw at him. There had, I knew, been one major change in his life. His girlfriend, Vera, had given birth to a baby daughter. They were living with Vera’s parents in Nairobi, but they wanted to get married and find a place of their own. The problem was the bride price. Mike was worried that his family, which in fact was not wealthy, wouldn’t be able to pay it.

Kenya seemed different, too—slightly more ominous than before. The papers were full of gruesome crime stories, and tension between Africans and the mostly Indian merchant class seemed at an all-time high. The few rural Masai wandering the streets of Nairobi looked more irrelevant than ever. With their beads and red cloaks, they remained the most familiar symbol of Kenya. But thanks to more than 25 years of one-party rule and deeply entrenched corruption, Kenya was increasingly just another strife-torn, debt-bound, quasi dictatorship. The plight of the 377,000 Masai, about 1 percent of the country’s 30 million people, hardly qualified as a problem.

An hour out of Nairobi we dropped 3,000 feet down the Laikipia Escarpment to the Great Rift Valley. Ironically, a giant satellite dish marked the entrance to Masai country; alongside it, giraffes bent to graze on the low acacias, while clusters of zebras and gazelles drifted across the landscape, indifferent to the larger herds of cattle.

We provisioned and spent the night in Narok, the administrative capital of western Masailand and gateway to the Masai Mara National Reserve—Kenya’s top tourist attraction, a huge, rolling, animal-rich grassland that lies just north of Tanzania’s Serengeti Plain. Narok is a frontier town. By night it swells with young Masai in from the bush looking for a buzz; by day the tourist minibuses roll through, air conditioners roaring. In theory, all the gate receipts and lodging fees from the Masai Mara (which is administered by the Narok County Council) are supposed to flow back to the community, funding roads, schools, and health care. But somehow, year after year, it all disappears. One look at the row of shiny Land Cruisers parked in front of Narok’s hostelry of choice, the $10-a-night Princess Hotel, told us where.

“Big shots,” Mike said. “The people who matter.

“The problem with Kenyan politics,” he went on, “is that no one respects you if you are elected or appointed to office and you don’t take the money. The actual saying is, ‘If you go to Narok and you come away with nothing in your pocket, you have to be daft.'” He laughed, but I noted a trace of bitterness.

Mike’s mood improved when we set off the next morning, the Pajero teetering under a Joad-like pile of sleeping pads, fresh produce, and the inevitable extra passengers—a student on leave, a distant cousin of Mike’s, and the deputy civil chief for the Loitas. About 20 miles southwest of Narok, the tarmac came to an end. We turned south off the road to the Masai Mara, then headed east into the Loitas. The track was laughably bad; we bounced along in first gear for miles at a time. As if in compensation, the countryside grew more beautiful, morphing from scrubby flatlands to undulating, gladed ridges carpeted in bright green grass and wildflowers.

At one point, Mike got out of the car and shot a few panoramas with Liz’s video camera. He had vague notions of doing a short documentary piece on the Loitas, and I taped him doing a stand-up. “Everyone is happy here,” he said. “There’s plenty of milk right now. They’re wallowing in it.”

To the south was Tanzania, not so distant now. We picked out the great volcanoes of the southern Rift, each with its own distinct profile: broad Gelai, broader Kitembene, the zebra-striped Ol Donyo Lengai, and the massive Ngorongoro Crater. Kilimanjaro was farther east, its snowcap lost in the clouds.

We left the road at Murja, about five miles south of the sleepy trading post of Morijo. One of Mike’s four sisters, Mercy, had married a man from there, Mokope Ole Nooseli. There was no road, so we climbed over a steep hill in four-wheel drive, pushing slowly through fields of wild mint and hibiscus that grew higher than the vehicle. The boma, or homestead, comprised several large fields of maize, a half-dozen traditional mud-and-dung Masai huts, and a corral of tall cedar stakes, plus a tin-roofed house that belonged to Mokope’s older brother, Francis. Mike had not seen his sister for a year, and they shyly shook hands. He and his diminutive brother-in-law warmly embraced. Although Mokope was a bit older than Mike, in his early thirties, both were members of the same “age-set,” a brotherhood of men within the tribe who go through coming-of-age ceremonies at the same time.

Francis, Mokope, and another thirtysomething in-law, Lulunken Ole Nkulaai, helped us look for a campsite. We settled on a little grove at the top of the hill we’d just crossed—the Hill of Milk, so named because cows who grazed there always returned with swollen udders. Francis offered us a goat, and Mike enthusiastically assisted in the butchering, eager to show his relatives that he still knew how. Later, as Mokope stretched strips of the meat on sticks and jabbed them into the ground next to the fire, Mike made a pasta sauce of tomatoes, onions, and garlic.

By now a small crowd had gathered—tall, red-robed men with dangling earlobes who’d walked up from the surrounding bomas to see who the newcomers were. They weren’t so sure about Mike’s spaghetti.

“Are you eating worms?” one man asked. The cucumbers I’d sliced for a salad were greeted with universal revulsion. I made a little speech about the importance of balancing the food groups, but Mike refused to translate it.

“That’s a waste of breath and energy,” he said.

OUR EXPLORATION OF THE LOITAS began the next morning when we drove Mokope and his infant son—who had a giant fungus growing out of his ear—to a medical clinic in Olorte, 20 miles and two hours away. The following day, Mokope, warming to the role of tour guide, led us to the top of the Hill of the Tick, which overlooked the Orng’Arua Valley. At the end of the valley the forest began—the famously disputed Naimina Enkiyio. It ran all the way to the eastern edge of the Loitas, then down the escarpment to the floor of the Rift. Mokope didn’t know how many miles across it was, only that a man could walk it, in the dry season, in 12 or 14 hours.

A few days later we drove to the northeast corner of the Loitas, then hiked to a pass where cattle are driven up the ridge and then down to the market town of Narosura. It was called enaeni’inkujit, “the place where grass is bound.” “This is the middle of nowhere,” Mokope said, through Mike, as we looked it over. “There are no bomas around, and no one to come to your rescue, even if you yelled.” He bent down, grabbed a handful of grass, and tied it in an overhand knot. “If you’re going north, you bind the evil of the buffalo-infested forest that lies below. If you’re going the other way, toward the grasslands, you bind the evil of lions.”

We climbed a hill above the pass; there was a huge north-south view. The wind blew softly, carrying the sound of cowbells. We sat in the shade of a lalechwa tree, and Mike showed off a trick he’d learned as a kid, crushing the downy leaves until they emitted a soft perfume. Warriors used it as deodorant, he said, stuffing it under their armpits.

Mike could get pretty wistful when he talked about his childhood. The second of three sons, he’d been picked by his father to become the family herdsman, while his older brother was tapped for secondary school. Mike hadn’t objected. A bright but stammering child, he loved animals and loved playing in the bush. It wasn’t all idyllic, though. One day when he was five, he and a playmate jabbed a stick in a beehive to see what would happen. The bees swarmed, caught up with the other boy, and stung him to death. Another time, when Mike was eight and playing hooky, he and a friend followed the blood trail of a buffalo into a thicket. The next thing he knew he was spinning through the air. The buffalo—which had been shot by a ranger the night before—had gored him in the stomach and broken his collarbone, and Mike just managed to climb a tree before it finished him off. He was so scared that his brother had to cut the tree down to get to him. He was in the hospital three months. “When I came out, I had a different attitude about school,” Mike said. “I started to work like crazy.”

Mike turned out to be a better student than his older brother. So good, in fact, that he wound up second in the entire district in his primary exams. With his mother’s encouragement he applied to Alliance, a prep school in Nairobi with an English headmaster. His father didn’t want him to go. He had to sell five cows worth $100 to $150 each, a huge sacrifice that marked the beginning of Mike’s alienation from his disapproving father.

The first year was total culture shock. His classmates were the sons of cabinet ministers. “These kids have already been to Europe and America, and I’m learning how to switch on a light,” Mike said. Still, bit by bit, he learned how to swim, how to use a library, how to trust his teachers. Mike sighed and leaned back in the grass. “I was a star with a bright future when I was a kid,” he said. “Every neighbor wanted me to befriend his daughter.”

At 16, Mike returned home for the most important Masai ritual of all: circumcision. He went through it in the traditional style, sitting on a cowhide with a dash of cold milk for an anesthetic, as the oldoboro, or rustic surgeon, swiftly made the cuts. Mike’s father timed the whole operation on a stopwatch. It took 47 seconds. Mike said the main thing was not to flinch. The slightest show of pain would disgrace not only the circumcisee but his entire family.

In the grass beside us, Mokope and Lulunken grunted their approval. Despite their limited English, they seemed to know what Mike was talking about. They were eager to share tales of their moran days—a sort of golden farewell to adolescence that starts right after circumcision and traditionally involves an extended period of wandering, cattle rustling, potentially fatal lion hunting, and all-out partying. “No one would tell you what to do, and you would always be offered milk as you went from village to village,” Mokope told me. “There were always girls available, and we could lie in with them in the morning. I didn’t go on many cattle raids. We would just steal one or two to eat, and if we were caught we had to pay.”

Mokope laughed mischievously. “But I was never caught. I was blessed by the

laibon

.”

Lulunken had taken his moran stint more seriously. In seven years, he’d amassed a herd of 50 cattle, the beginnings of real wealth. And he’d been on several lion hunts, some of them successful. They were officially illegal, of course, but if lions attacked livestock, they were considered fair game.

Mike listened attentively. He’d been a moran for just three months, during the school holiday. “It was fun, but I didn’t go on any lion raids. You can get thrown in jail for that.”

He reconsidered. “OK, I joined a raid, but thank God we didn’t get it. I wasn’t going to be the one to throw the spear or to grab the tail. Those are the two dangerous jobs, and there are so many casualties.” Mike glanced at his in-laws and smirked. All in all, he confided, he’d had a better time as a Boy Scout in Nairobi. “We’d camp in the forest behind Karen, and my job was to spy on the other patrols and steal their techniques, how they pitched tents, dug their latrines. Then I would write it all down.” He laughed. “That’s really where I learned to camp.”

In the early 1990s, a three-year drought struck Masailand. Mike’s father refused to sell any cows, and one by one they died. Mike said his father was obsessed with not being seen by friends and neighbors as selling out to modernity. There was a lot of pressure that way in Masailand—a kind of fundamentalism that scorned all things new. By the end of Mike’s third year at Alliance, in 1993, the family had only five cows left. There was no money to send him back, so he had to prepare for his secondary exams at the regional high school near his hometown of Narragie Enkare. His score was one point less than the threshold for law school.

Sitting here now, none of that seemed to matter. Mokope clearly loved his brother-in-law and even stern Lulunken seemed to respect Mike as a full age-mate. In Narragie Enkare, where we later spent an afternoon on the way back to Nairobi, I would get a slightly different impression. A market town surrounded by rich fields, it was not nearly as remote or traditional a place as the Loitas, and I was surprised to find that while Mike’s old classmates had herds and family grazing lands they were a clean-cut, upwardly mobile bunch also making their living in more modern ways—one a doctor, one a lawyer, one a flight attendant on Kenya Airways. They were glad to see Mike, the prodigy of their primary school, but once or twice I caught them looking at him skeptically. Mike hadn’t exactly made it in Nairobi, at least not yet. And when he did manage to set money aside, his plans never seemed to pan out. One of the first things he wanted to do was build his mother a new house. He’d bought the most expensive materials—40 cedar posts, dear commodities in a country largely stripped of timber. But six months later, he’d come home to find that his father had sold half of them and spent the proceeds on alcohol.

Mike freely admitted that he didn’t know what he was going to do with his life. He didn’t regret leaving Masailand behind; he preferred the teeming streets of Nairobi. It was just that in the big city the way forward simply wasn’t as clear as it had been when he was a bright kid in a top boarding school. “Those were good days,” he said, gazing across the Rift. “We were young and had no problems, and thought only about today. Tomorrow we were going to college and then to get a job. It was all going to take care of itself. But it didn’t work out that way.”

ONE MORNING A WEEK into the safari, a young boy walked into our camp, bowed his head for all of us to touch (as uncircumcised Masais traditionally must), and announced that the laibon—whose name was Mokompo, and who was the most famous laibon in western Masailand—would speak to us that afternoon. Mokompo’s father, Simel, had been the laibon before him, and Simel’s father, Senteu, had been a son of Mbatian, who’d been chief laibon at the end of the 19th century. People came up from Tanzania to consult with Mokompo, driving anywhere from five to four dozen cows before them as payment. We’d requested an audience through Lulunken, who turned out to be his nephew. Thanks to the connection, we scored a deal—3,000 shillings, or about $40, still a princely sum in a country where the average man makes $1 a day.

Mokompo lived at the end of the Orng’Arua Valley, on the far side of a bog. As we drove there, Mike explained what Mokompo was—not exactly a witch doctor, but a “ritual expert.”

“What’s the difference?” I asked.

“The difference being that he’s informing you of a ritual that will cleanse you, not telling you how to get rid of your neighbor who’s a nuisance.”

We parked under a solitary tree and crossed the bog in single file. Mokompo, a tall, still-muscular man in his late sixties, received us in a tin-roofed shed. His outfit consisted of a robe of hyrax fur lined with purple cotton and two shukas, or togas, one purple and yellow and one black and green. His face and temples were marked with white paint, and he fanned himself regally with a zebra-tail whisk.

“He doesn’t look as scary as I thought,” Mike whispered as we took our seats on a low bench.

A small hole in the roof sent a shaft of sunlight into the otherwise dark room. An old man in the corner pulled a medicine bottle out of his earlobe and tapped a pile of snuff into his palm. Mokompo sat on a stool, picked up the liter of scotch I’d brought as a gift, and began to speak. Mike translated.

“How much is this good for?” he asked.

“That would last a man about a week,” I said.

He poured some into a cup. “It takes a smart guy to take this,” he said. “You can burn your liver unless you drink it slowly. I’ve seen this by pouring some on the liver of a slaughtered goat—it burned.”

He took a sip, wrinkled his eyes, and gave us a sly, knowing look. “This stuff isn’t for dummies,” he said.

He poured more scotch and then had a boy put the bottle away in another room. Finally, at Mike’s prompting, he began to tell the story of how his family had come to the Loitas. Mike picked up the video camera and started taping.

It was a long story, and the scotch had to be fetched several times. It began with Mbatian. When he was old and bedridden and nearly blind, he had called in his son Lenana, his favorite. “The time has come for me to hand over my powers to you—come tomorrow morning,” Mbatian said. Another son, Senteu, the same age but from a different mother, overheard this and got jealous, so he planned a trick. Very early the next morning he went into his father’s hut, pretending to be Lenana. He gained everything—the horn from which the stones were cast, and his father’s blessing as well. Then he left.

Lenana had overslept, and came to see his father late that morning. Shocked, Mbatian cried: “To whom did I give the blessing?” Then he spat in Lenana’s hands to bless him, so Lenana could also become a laibon. “By then the British were here,” Mokompo continued. “The Masai were famed for their fierceness, and the British wanted to befriend them. They learned of Lenana’s rivalry with Senteu and befriended Lenana. Lenana gave them the land in Laikipia they wanted. In exchange, the British banished Senteu to Loita. The idea was that he and his family would perish from disease. Somehow, they survived.”

Mike put down the camera. His eyes were wide with surprise. “I’ve never heard this version of the story,” he said. “I’ve always been told that the British exiled Senteu to the west side of the Great Rift Valley because the rest of the Masai complained of his witchcraft. But this version explains why Lenana gave out Masai land, the so-called White Highlands, to the English—to get rid of his rival. It’s always been a burning question to me.”

Mike was genuinely excited. “What Mokompo is saying is that Senteu wasn’t the traitor; ultimately Lenana was,” he said. He smiled and called it “the west-side story.” For Mike, this was a clear explanation of the Loita’s “reputation for authenticity,” as he put it, but also, I thought, a budding political insight. As a nomadic people, the Masai lacked centralized leadership—or had since the days of Mbatian. The British had cleverly exploited a fraternal power struggle, and the Masai had paid dearly.

TWO DAYS LATER we crossed the river at the bottom of the Orng’Arua Valley and headed for the Naimina Enkiyio. The kudzu-like foliage at the edge of the forest was so dense that at first we couldn’t find an entrance. Finally Mokope slipped into the cool dark, and we followed, dodging great lianas and head-high nettles. Eventually we stumbled onto a sort of boulevard. Nearly as wide as a road, it was covered with round tracks ranging in size from large Frisbees to small garbage-can lids.

Elephants. Mokope said you didn’t want to be here late in the day, when they came rumbling down to the valley to water. I tried to imagine it—an African Pamplona.

“What else is in here?” I asked.

“Everything,” Mokope said.

“Gorilla?”

“E-e,” he said, making the dipping sound that means “yes” in Masai.

“Rhino?” Mokope took a while to answer. “Well, he’s not ruling it out,” Mike translated. “He’s never seen one, but he has seen a wallow and some signs.”

As for the forest’s name, all Mokope knew was that at some point in the past an eight-year-old had wandered off into the woods. Some said it was a girl herding cattle; others, a boy in pursuit of wild fruit. Either way, the child never returned. The story was that he or she grew “wild, enormous, hairy, and awesome, like a very big tree.”

The Loita Masai had always used the Naimina Enkiyio as a source of honey and medicinal herbs, Mokope told us. Most important, it functioned as a “buffer zone” where cattle could water in the dry season.

In 1993, when the Narok County Council first moved to take possession of the forest, it cited the Local Government Act, which empowers county councils to establish game reserves, parks, and forests. There was a need to boost tourism revenues and at the same time ease congestion in the neighboring Masai Mara. The press reported that a group including a South African developer, the son of a top Kenyan party leader, and a senior cabinet minister—none of them Masai—wanted to turn the area into a private tourist resort.

In the Loitas, the fear was twofold. The Masai would be deprived of access to the forest, their presence being anathema to the tourists’ “wilderness experience.” And second, the forest itself would eventually be “gazetted”—split up and sold. Management at Ilkerin, a Loita community development project, engaged a lawyer who obtained a temporary injunction. “All land in Loita, including the Naimina Enkiyio, is owned and used communally,” an Ilkerin manager wrote in an editorial in The Weekly Review.

The standoff lasted until 1997, when Stephen Ntoros, a 37-year-old Ilkerin training officer who had helped lead the fight against the forest falling into council hands, was himself elected chairman of the council. “I have managed to put in place a demarcation process that means Loita Forest will be set aside as a biological and cultural heritage of the local community with its own title deed,” he announced. It sounded like good news, and a grateful community allowed Ntoros to build a home on a hilltop overlooking the forest.

But Mike wasn’t sure the dispute was over. Two years earlier Kenya’s president, Daniel arap Moi, had paid a surprise visit to Loita, flying in by helicopter. Now Ntoros, the local hero, seemed to be planning to run for parliament. Could development of the forest be the price for Moi’s support? Things would be a lot clearer after the upcoming elections in December 2002, Mike said. After what would be 24 years in office, the 77-year-old Moi had agreed to step down, and no one knew who would emerge with the power.

After stumbling through the forest for a few hours, we were heading out when we came upon it—an eight-foot-high wire fence strung on wooden posts and slicing off what looked like a fairly significant chunk of forest. The fence, Mokope said, belonged to Ntoros’s father, who somehow had acquired title to the land. Later he pointed out the chairman’s house, a large metal-roofed structure at the edge of the woods.

It was hard to read Mike’s reaction. He looked at the fence, walked along it, stroked his chin, but didn’t give much away. Still, it must have been a pretty low moment for him. We’d come all this way to walk through an ancient, supposedly undivided forest. Yet here was a towering fence and a trophy house.

It was “grabiosis,” Mike said—shameless land grabbing, the very thing that was going to finish off the Masai. How could a declaredly pastoral people, whose way of life depended on large herds and vast amounts of open range, survive in a world of private property?

We walked back to the jeep in silence.

An hour later we were bogged down in the meadow, all four wheels mired to the axles, and 20 minutes after that we were on foot in the African bush with night falling and one sketchy flashlight among us. I suppose, given our state of mind, that it should have been a gloomy slog. But the walk restored us. There was one scary moment, when we startled a small herd of zebras in the midst of a darkened meadow, and they scattered crazily into the night, hooves thundering. But if the lions were out there, they let us pass.

“They would never attack so many,” Mokope said, once we were back.

“Well, maybe not five of us,” I said. “But what if we’d been two or three?”

Mokope paused to consider his response. “Probably not,” Mike said. “But he’s not ruling it out.”

ONE HUNDRED MILES SOUTH of the Loita Hills stands another Masai landmark, one even more venerated than the Naimina Enkiyio. The cosmic punch bowl of Ngorongoro Crater, 11 miles in diameter, had been Mbatian’s home, the majestic throne of Masailand. In 1956, it became a national park, and the stubborn Masai who remained were finally evicted from their villages about 20 years later. From an economic standpoint, Ngorongoro had been a great success—one of the destitute country’s biggest moneymakers.

When Mike proposed an investigatory safari, Mokope and Lulunken immediately signed on. They weren’t particularly interested in park politics, but Lulunken had been down that way as a moran, and Mokope had roamed just as far selling veterinary medicine.

It wasn’t easy to get out of the Loitas. In the first place, there was the Pajero, which took the better part of a day to dig out of the swamp. And then there was the question of Tanzanian visas. Liz and I had none, but Francis, Mokope’s brother, had drafted a flowery letter, asking the authorities to look after us. I wasn’t sure it would work, but Lulunken just shrugged. “It’s all Masailand,” he said.

The Tanzanian side of the Loitas was even greener than the Kenyan. There were big shambas, or farms, with endless fields of maize, roads with culverts, and in the border town of Loliondo, the shocking sight of electrical lines. The district officer there barely glanced at our letter. “Please make yourselves welcome in our country,” he said. “Camp wherever you like.”

We did, dropping through the cactus country of the Sonjo tribe to the very rim of the Great Rift Valley, and then plunging down the final step of the escarpment on an unspeakably bad road called 17 Corners. At the bottom was a vast soda lake called Lake Natron, a vision out of the Old Testament, with dust devils spinning across its alkali flats and crimson flamingos wheeling up to the heavens. At the end of the lake rose the perfect, smoking cone of Ol Donyo Lengai, Africa’s Mount Fuji. I thought it one of the most amazing landscapes I’d ever seen, but the next morning Mokope said he’d had enough. He’d been kept awake by malarial mosquitoes and something Mike referred to as a “car-alarm bird” because it slept all day and went off all night.

“If the land committee gave me some land here I wouldn’t even attend the meeting,” Mokope said. “It’s too hot. You’d wipe your skin off after a day.”

Eight bone-crushing hours later we were at the gate of Ngorongoro National Park. Now it was my turn to moan—I couldn’t believe the $155 entrance fee. But the view from the rim made it all worthwhile. Mokope and Lulunken grabbed the binoculars from each other, giddily pointing out every elephant and buffalo in the crater, while Mike, beaming wildly, filmed them up close. Liz and I decided to splurge, and the five of us checked into one of the tourist lodges overlooking the crater. Mokope and Lulunken had never been in a hotel before, and they entered suspiciously, clutching their rungus, wooden staffs, for protection. Lulunken took a shine to a girl in the gift shop and asked her to marry him, but she pointed to Mike, crisply turned out in a clean polo shirt. “I want that one,” she said.

Mokope and Lulunken didn’t have any extra shirts, so before dinner, they simply swapped. At the buffet table they went straight for the nyama choma, roasted meat. Afterward we sat in front of the fire like a bunch of colonial-era codgers. We were at 10,000 feet, and it was cold. “Yesterday we were almost dying of heat,” Mokope said. “Today we’re freezing. The human body is almost useless.”

Lulunken’s gaze kept wandering around the room. “They will be subject to a cross-examination when they get back,” Mike said, “and they will have to recount the trip in the smallest detail.”

Was Ngorongoro Park what Mokope and Lulunken wanted the Loitas to become? No, they said, but they knew the place could not stay the same forever. One thing for certain was that more schools would have to be built. “The Masai always thought of education as doom,” Lulunken said, “so those kids loved by their fathers were never sent off to school. But the Masai were rich in those days. They don’t have big herds anymore, and school is the only way to ensure the future.”

WE TOOK A DIFFERENT ROUTE back to the Loitas, dropping down the west side of Ngorongoro Crater to Olduvai Gorge and then turning north along the edge of the Serengeti Plain. Down there it was already the dry season, and for a while we fought to stay ahead of our own dust cloud. Then, almost imperceptibly, the sere began to give way to green, and the first scattered game—gazelles and impalas—began to appear. For the next few hours it was as if we were climbing the great chain of life: we saw ostriches, hyenas, zebras, and eland, and the mighty armies of wildebeests that stretched in black columns to the horizon. Then the low hills, and finally the gorgeous green grass of the upcountry pastures, the painted cattle, and the Masai themselves.

“Look at that grass,” Mokope said. “Why would anyone live anywhere else?”

We dropped Mokope and Lulunken at dusk in a village a few miles from Murja. Inside the thorn enclosure some young warriors were dancing, jumping high in the air with their arms at their sides. Mike watched for a minute before climbing back into the Pajero. “They are asking for a goat,” he said. “Tonight in the bush they will be feasting.”

It was another 85 miles to Narok. For a while we listened to a gospel tape Mokope had liked, then it was just the vehicle, bouncing and grinding. I glanced over at Mike, trying to guess what he was making of the whole long journey, what story he was shaping, what moral he might draw. I remembered a piece he’d written for his magazine, Nomadic News, in which he’d quoted an elder in Narragie Enkare on the role of the younger generation of Masai. “They live in their complex towers in towns and only come home to bury their dead and during Christmastime,” the old man had said. “These prodigal sons and daughters should come back home and contribute to the development of the community that made them what they are today.” Was Mike thinking now that he ought to heed the advice and go back home? Was it even possible?

Mike actually hadn’t been thinking about that at all. “I remember something a lawyer in Nairobi once told me,” he said. “‘We cannot live in a cocoon,’ and I think he was right. We’ll hold on to some things, and we’ll lose some others —it will have to be a balance. I laugh when I hear people say the Masai are doomed. Perhaps their way of life is doomed, but the Masai themselves, they are survivors.”