IN 2004, PARADISE WAS PUMMELED. Late December’s tsunami in the Indian Ocean, caused by a 9.15-magnitude underwater earthquake west of Sumatra, destroyed beach resorts in Thailand, Sri Lanka, and the Maldives. More than 230,000 people perished—thousands of travelers among them—and hotels, restaurants, and other businesses were ruined along with the beaches. Earlier, in August and September of that year, four major hurricanes crushed the Caribbean community, racking up more than $6 billion in damages across the region. In both Southeast Asia and the Caribbean, many of the affected towns and provinces depend on tourism for their livelihood, so once the survivors were accounted for and the dead were buried, reconstruction and rebooking quickly became the top priority. But just how do resort areas bounce back from such devastation? To answer this question, we checked in on two disaster-struck islands: Phuket, off the western coast of Thailand, and Grenada, one of the southernmost islands in the Caribbean.

Before the tsunami, Phuket was one of the most popular beach destinations in Southeast Asia, generating more than two billion tourist dollars in 2004. On the day of the disaster, December 26, 2004, three giant waves slammed into Phuket’s beaches, flooding hotels, uprooting trees and debris, and killing almost 300 people—with more than twice that number still unaccounted for. While the disaster was horrific, the lingering perceptions of the devastation have also proven detrimental: Due to extensive media coverage of the most severely hit areas in the Indian Ocean region, most people assume that the entire 30-mile-long island was leveled; in fact, only 12 percent of Phuket’s rooms were damaged by the disaster. Still, tourism in Phuket has dropped 65 percent, and in the first half of 2005 the island lost more than $1 billion in tourism revenue.

In the Caribbean, no island suffered more than Grenada, traditionally considered south of the hurricane belt. Ivan, the first major hurricane in recorded history to have formed below ten degrees latitude in the Atlantic Basin, struck on the afternoon of September 7, 2004, with winds of at least 111 miles per hour. Its eye passed just south of the red-roofed harbor town of St. George’s, ripping apart nearly everything in its path. Thirty-nine people were killed, and 90 percent of the island’s houses were damaged. The tourism industry, still recovering after lean post-9/11 years, was upended. Total damage came to nearly $1 billion, more than 200 percent of the country’s gross domestic product.

After both tragic events, aid poured in from around the globe. The United States, England, China, India, Trinidad and Tobago, and Cuba donated $58 million to Grenada. While the Thai government has refused monetary aid, more than $27 million has entered the country through post-disaster relief efforts. Now the two islands, victims of very different catastrophes, are gearing up for the high season facing equally different situations: Grenada, despite being slapped by Hurricane Emily this past July, has recovered further than anyone would have expected and anticipates a good winter season; Phuket, on the other hand, has been open for business for months, but no one’s biting. Take a look at how these islands are faring and remember this: The best way you can help is to book a plane ticket and go.

Case Study: Phuket, Thailand

Ready and Waiting

HARDEST HIT IN PHUKET was Kamala, a beachfront village on the west side of the island. By the time the third wave struck the enclave, many residents had escaped up the hill behind the village. After the chaos and shock of the first few weeks, survivors displayed characteristic Thai fortitude and began to rebuild from the rubble, anticipating the return of the tourists. One store owner handpainted a sign and hung it in front of his store: even tsunami cannot beat us. we make the best homemade pizza. But nobody came to eat.

More than 95 percent of Phuket is up and running again. Not only have the beaches been cleared of debris, but many are wider—by as much as 30 feet in some spots. Restaurants and bars have been cleaned and remodeled, and shops have been restocked with everything from sarongs to sequined handbags. The only thing missing now is the tourists. One day last April at the Terrace, a popular seaside restaurant, three musicians played the pan flute, xylophone, and lute, but there was only one couple dining in a room that seats 60. ���ϳԹ���, there were no bumper-to-bumper backups of cars, motorbikes, or bright-red minivan taxis headed to the beaches, because the seasides were deserted. As of August, hotel occupancy was down 65 percent from last year.

Phuket’s tourism board has responded by working with local businesses to woo visitors with two-for-one deals, extra meals included in the price of a hotel room, and lower airfares. In addition, the Thai government has teamed with Thai Airways International and others to promote its “Best Offer”—three days and two nights at any of 11 different resorts for as little as $80. The Trisara, a brand-new five-star resort on the Andaman Sea, is offering villas—complete with a 30-foot infinity pool, 37-inch plasma TV, and a yacht available for charter—for nearly 20 percent off. Meanwhile, Amanpuri Phuket and Mom Tri’s Villa Royale hotels have cut their prices by 50 percent.

Still, the island is like a ghost town—literally. Much of the 60 percent decline in visitors from other Asian nations is a result of Chinese and other nationalities’ cultural and religious beliefs that the spirits of the missing are still roaming the beaches. (More than 3,000 people remain unaccounted for across the region.) To win these tourists back, a highly publicized series of events is planned, culminating on December 26, 2005, the first anniversary of the tsunami. Monks and priests of all religions will “free” the departed souls and give permission for visitors to return to southern Thailand.

Tourists are also concerned about safety, should another tsunami occur. The Tourism Authority of Thailand is developing what it calls the “Safer Beach” concept, a plan that includes the construction of a “Memorial Gateways” wall in a heavily touristed area of Phuket, to serve as a permanent memorial to those who lost their lives while, in concept, slowing down any advancing floodwaters. The Thai government also developed a Tsunami Early Warning System, which has been operational since late May and is monitored 24 hours a day. (It was successfully put to the test in July, when it detected a 7.3-magnitude quake more than 400 miles from the island.)

Holidaygoers and merrymakers may not have returned en masse to Phuket yet, but judging by the locals’ speed in rebuilding after the disaster and the government’s concerted effort to shore up the tourism industry, not even the tsunami will keep the Thais down. A T-shirt that has cropped up in markets across the island underscores that resilience. On the back is a list of trials the region has faced in recent years: a post-9/11 bomb alert, worldwide panic over SARS, mass bird-flu hysteria, and now the tsunami devastation; the front of the shirt reads still alive.

Beyond Phuket

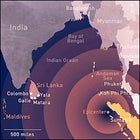

Across the Indian Ocean region, communities are still recovering from the 2004 tsunami

DESPITE THE TRAGEDY IN PHUKET, the island fared better than other Indian Ocean destinations—places like the nearby Thai island of Koh Phi Phi; the Maldives; and Galle, Matara, and Yala, in Sri Lanka. “When I arrived in Galle in April,” says Alexander Souri, owner of Massachusetts-based outfitter Relief Riders International, “beachfront resorts were still rubble, just plaster and brick on the ground.” Images like that, coupled with fear of another tsunami, have sent tourist numbers plummeting across the region.

Koh Phi Phi suffered extensive hotel damage, including the loss of 1,400 rooms, and is projected to give up $90 million in tourist revenue in 2005. In the Maldives, the tsunami flooded the heavily touristed atolls of Mulaku and North and South Male, destroying hotels and restaurants. By mid-August 2005, the country was estimated to have lost $250 million tourist dollars since the disaster. Sri Lanka’s burgeoning coastal tourism industry suffered as well, losing $42 million through the first half of 2005.

Thanks to locals’ perseverance and foreign aid (the U.S. government has pledged nearly $1 billion in support, with private donations topping $1.2 billion), many of the nations that were underwater just nine months ago are speeding forward with the reconstruction process. The damaged hotels gracing the southern beaches of Sri Lanka are 67 percent up and running, and those in the Maldives are 87 percent in service. And though Koh Phi Phi is still in the early stages of rebuilding, American outfitter Big Five ���ϳԹ��� Travel is offering day trips to explore the island’s limestone cliffs by boat.

The governments of the affected areas are gearing up, too. Last spring, the Maldives’ Tourism Promotion Board began spreading the word about the archipelago to travel agents and tour operators across Asia. They also sent delegations to parts of Europe in hopes of regenerating foreign interest in the islands. Thailand has aggressively pursued the airlines, setting up deals with Thai Airways International, Bangkok Airways, and Orient Thai Airlines to reduce fares and bundle flights with discounted stays at resorts. And in September, Sri Lanka launched a $4 million advertising campaign to lure European travelers back to its beaches and highlands for the upcoming high season.

“The attitude should not be ‘Look how terrible it was.’ The attitude should be ‘Look how far the area has come to recover,’ ” says Ashish Sanghrajka, Big Five’s VP of sales and partner relations. “There’s still lots of great things to see and do there.”

Case Study: St. George’s, Grenada

Full Speed Ahead

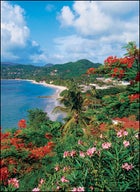

NEW GROWTH: St. George’s is flourishing, thanks to a resolve to “build back better”

NEW GROWTH: St. George’s is flourishing, thanks to a resolve to “build back better”HURRICANE IVAN gave an unfathomable shock to a nation whose unofficial motto is “God is a Grenadian.” It had been just shy of half a century since the last serious hurricane struck Grenada, and even as Ivan was bearing down, few residents sensed real danger. “We were so naive,” says Lawrence Lambert, managing director of the Flamboyant Hotel, which sits on a hill above the southern end of Grand Anse, Grenada’s celebrated two-mile stretch of white-sand beach. “I thought maybe some doors might blow in.”

In fact, the Flamboyant, like so many other buildings, was pounded, losing its main restaurant and all of its roofs. Ivan was so good at dismantling roofs, locals started referring to the storm as Hurricane Roofus. Very few buildings were erected with hurricane survival in mind; analysts now say that $4 metal hurricane straps, which help keep a roof fastened to the top of an exterior wall, would have greatly reduced the islandwide structural damage.

Now—despite all this destruction and despair—Grenada is bouncing back, at a pace no one could have imagined in those initial grim post-hurricane days. After the first dazed month, insurance claims began getting settled; construction materials made their way to the island; teams of workers put in countless hours of hard, hot labor; red tape was cut through; and the government mandate to “build back better” began to seem possible. By the end of this year, 94 percent of the island’s nearly 1,600 hotel rooms will be available to guests. Among them, the rebuilt Spice Island Beach Resort, on Grand Anse, will reopen as a five-star hotel. A few hotels never closed: the candy-colored cottages of Bel Air Plantation, which were built to Florida hurricane standards by American owners in 2003, and down-but-not-out True Blue Bay Resort, which provided lodging and meals to an endless procession of insurance adjusters and embassy personnel in the months following the storm. The last major hotel to reopen, LaSource, will welcome guests beginning sometime in 2006.

Of course, the island still bears Ivan’s scars. Some are obvious, like the many houses—especially the more rural ones—sheltered by blue tarps. Some are less obvious, like the thatched umbrellas at the understatedly chic Laluna resort, put up on the beach to replace shade trees lost to the storm. Tourism is rebounding: In August, the island was expecting around 15,000 visitors, a return to almost 90 percent of last year’s pre-Ivan numbers. Meanwhile, the future of the nutmeg industry—which accounted for about half of Grenada’s agricultural-export earnings and supplied a third of all nutmeg worldwide—remains uncertain, as almost all of the island’s nutmeg trees were destroyed.

Challenges notwithstanding, visitors to Grenada this winter will find a heartfelt welcome from a nation that knows how crucial the return of tourists is to its economy—and its battered psyche. They’ll also find beaches that are clean and inviting. The reefs and wrecks off Point Salines are still great dive spots. The Morne Fendue Plantation House, high in the hills of Saint Patrick’s Parish, is still serving its astonishing soursop ice cream. And the nutmeg-dusted rum punches at True Blue Bay Resort’s rebuilt waterfront bar are as sweet—and as potent—as ever.