A few years ago, I went for a run with my girlfriend in the foothills outside our home in Santa Fe. It was early June, after work, and we planned to run for an hour or so, hoping to catch the evening light as the sun fell below the Jemez Mountains. We were going to take it easy. I was tapering for what would be my first 100-mile race a few weeks later. I had recently clocked my first 80- and 100-mile weeks after progressively building mileage over six months. I was 30 years old.

Before we’d made it a mile, a sharp pain radiated up from my foot. I stopped, expecting a cactus needle to be sticking out of my shoe. There was no needle. Dammit, I thought. I’ll jog it off. I hobbled on. No dice. I walked back to the car, waited a day, then a week. The pain didn’t go away. “Bone bruise,” the podiatrist said, jabbing my foot with a syringe full of cortisone. The day before the race, I jogged a mile around my neighborhood, just to test things out. Not great, but OK. I still ran the race. It wasn’t all that graceful, but I finished.

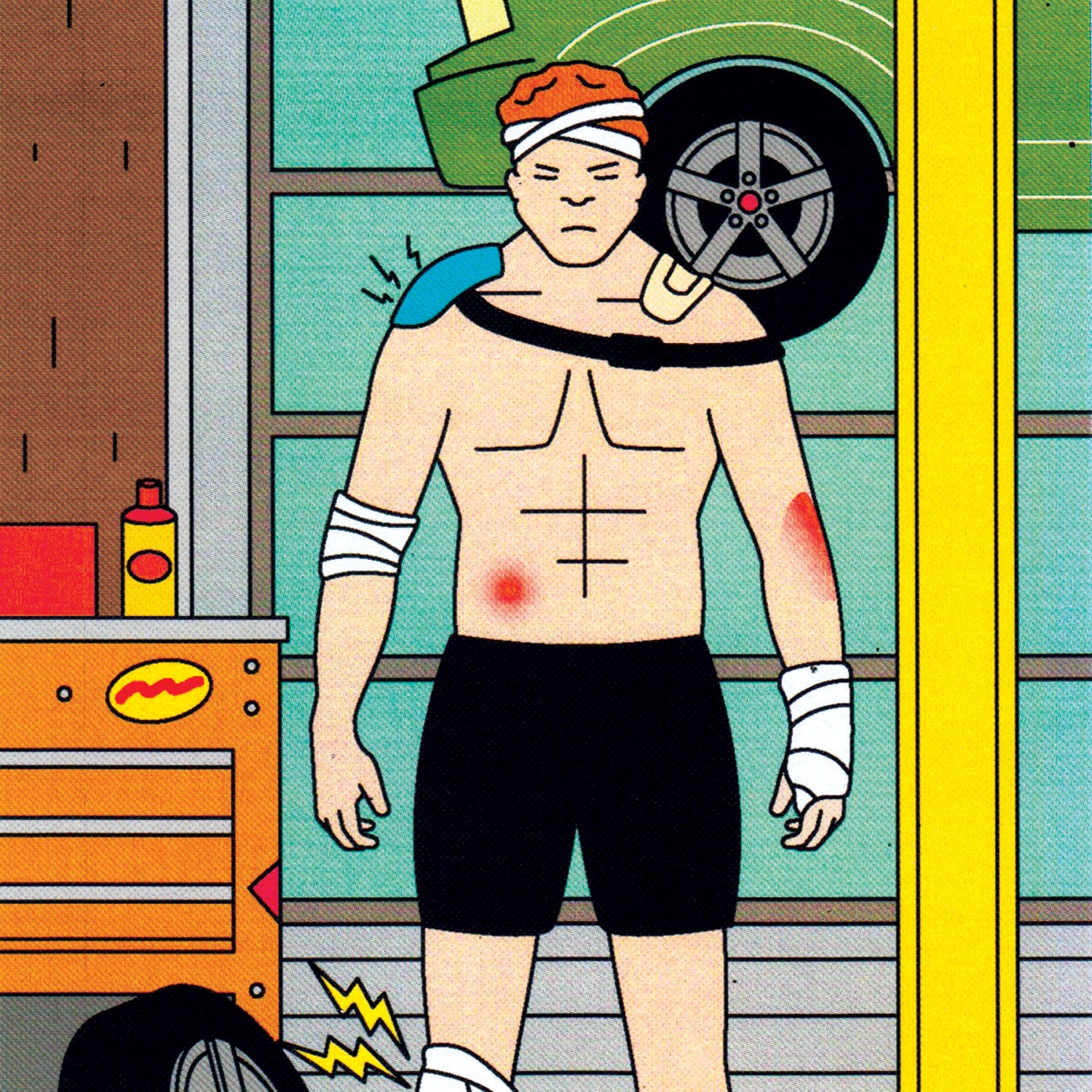

Four months later, a spry 31 and rebuilding for another event, I felt more sharp pains, this time in my knee. IT band syndrome. It seemed like it was time to take a break from running. I started climbing again, a sport I’d done for a decade that recently had taken a back seat to all that running. Within two or three months, I developed golfer’s elbow. I stopped climbing. Luckily, ski season was right around the corner. But soon a fall led to a separated AC joint in my shoulder. I went back to running. The pain in my knee returned, then migrated up my hamstring, where the tendons connect to the sit bone. Over to climbing I went. In no time, both of my shoulders were in agony—two strained biceps tendons. Dammit, I remember thinking. I was 33.

Before all this, my body had always done whatever I asked of it, like a new car fresh off the lot. Eighteen-hour days in Canada’s Purcell Mountains. Marathons on four weeks’ training. Seven hours of nonstop surfing in El Salvador. I pressed the gas pedal and the car accelerated. When I did occasionally get injured, there was nothing that a week on the couch—or a couple of extra beers—didn’t seem to fix. Youth, in other words, had not prepared me for getting older.

The hamstring injury was the most debilitating. I couldn’t sit for more than an hour without a dull pain pulsing through my leg, and it lingered for days. I went to an orthopedic doctor, who tugged on my leg for a few minutes, told me it was “a PT problem and not a doctor problem,” and charged me $200. I went to a PT. “Have you been stretching?” he asked. “No.” “Good! Don’t stretch. Can you walk up a flight of stairs?” “Yes.” “Wonderful. What about lifting a bag of groceries off the floor?” I started to get the feeling that his idea of “injured” was different than mine. Then I mentioned that, actually, I had been dealing with a raft of physical issues lately. “Is there some kind of overall bulletproofing routine I can do to, um, prevent all injuries in the future?” I asked, supposing that surely someone had solved this problem. He paused for a beat. “Have you tried googling it?”

The truth is, my body’s a work in progress. I will probably be doing some version of the clamshell for the rest of my life—nothing works perfectly forever if you ignore it.

This didn’t seem like particularly helpful advice, but I did as I was told. Turns out there’s a lot of information on the internet. Academic papers galore and lengthy case studies by Australian rugby trainers; YouTube videos by bodybuilders in aggressively tight shirts; British MMA fighters demoing mobility drills over soothing beats; skiers built like Gucci models executing gymnastic feats of strength; TB12, XPT, and other routines you should do Every Morning When You Wake Up! I tried them all. But the injuries didn’t go away, and more cropped up. A strained back, even something weird with my finger.

Eventually, I realized that I may just be feeling my age. Thirty-four, as of this writing. No shit, you may be thinking—athletes usually peak in their mid- to late twenties. But for me it came as a shock. (Where does the time go? etc.) It was also disastrous. No one expects to be, say, a soccer player into their sixties. But almost every runner or climber or skier I know has zero plans to dial back the days of deep powder, stacked granite pitches, or blissful singletrack. We are slaves to our passions. And so the injuries started to lead me down all sorts of scary existential alleyways: Who am I if I can’t do the things I love? It was extremely troubling to realize that what was once fresh off the lot was becoming a clunker—brake cables frayed, tires flat. I don’t think I met the criteria for full-blown depression, but I was very, very sad.

“The whole goal of adventure is seeing what new limits we can take ourselves to,” said , a nonsurgical ortho, in Missoula, Montana, who I reached out to in a desperate fugue after my girlfriend recommended him. It’s similar, he said, to what they’re doing in Nascar—pushing a car’s engineering to the absolute limit. “The difference,” Amrine said, “is that in the motorsports world, they love it when the machinery breaks. They spend all night reengineering it to work better. For us as athletes, when we break it’s a catastrophic end-all.” That’s it, I thought, no more sports for me. I guess I’ll take up day trading. But then he said something else: “And we don’t always want to do that tinkering and maintenance to get us better.”

Tinkering. Maintenance. These words were beacons of hope. In my case, tinkering involved a pretty straightforward prescription. “You need someone who will kick your ass,” Amrine said. He put me in touch with a PT he knew named Laura Opstedal, a woman who believes that even 90-year-olds should be deadlifting. Opstedal strapped me to a Humac Norm Isokinetic Dynamometer machine, which looks kind of like a dentist’s chair. Using a mechanized foot strap, she measured the relative strength of my hamstrings and quads. Then she put me on a treadmill, filmed me running, and sent the footage to a biomechanics lab. The results: my form was decent enough—no glaring deficiencies or giraffe-legged wobble—but my muscles weren’t nearly as robust as they should be.

“The demand you were putting on your body exceeded your capacity,” Opstedal explained, which was a nice way of saying You are not strong enough to do the things you are trying to do. When we exceed our capacity, we get injured, she explained. That initial injury becomes a never-ending cycle. You rest, you move less, your capacity shrinks more, you do your sport, you get hurt. Repeat. “Unknowingly,” Opstedal said, “you were caught in a downward spiral.”

To continue the tortured car metaphor: my engine was strong but the axles were rusted. I hadn’t developed a broad base of strength, and as I got older, heading out on a Saturday for a four-hour run or projecting a sport line at my limit wasn’t being supported mechanically by my nine-to-five desk job. I’m not unique in this regard. Opstedal sees athletes at her PT practice in Bozeman “all the time, all day long,” who are exactly the same. (I spoke with a half-dozen PTs for this story, and one of them, Michael Lau, cofounder of an online educational platform called the , described his typical client as “a 34-year-old male with a history of being athletic, knows a little about their body, but doesn’t have time to train the way they used to. Goes off very fine for the most part, but then stumbles into injury and can’t get over it.” It was comically on point.)

To pull myself out of the tailspin, I had to start from square one. I began with 15-minute runs that were so easy I felt silly putting on my running gear—Why not just knock this out in jeans?—and weights so light they were better suited to holding down sheets of paper. Exercises I hadn’t done since high school became routine: deadlifts, squats, presses. “In health care,” Lau told me, “the problems are complex, but the answers are often simple.” Slowly—painfully slowly—I added a little bit more week by week. But I kept at it. (Consistency was key: back when I tried treating myself with YouTube videos, I never knew whether I was on the right track; I would experiment with an exercise for a day or a week, then abandon it when I didn’t see immediate results. Not a good tactic.)

I’d like to be able to report that Opstedal kicked my ass so thoroughly that I now have an entirely rebuilt suspension, ready for the next 100,000 miles. The truth is, my body’s a work in progress. I will probably be doing some version of the clamshell for the rest of my life—nothing works perfectly forever if you ignore it.

The good news, though, came from Lau. “There’s nothing preventing you from getting back to where you were,” he told me. Amrine backed that up. “If you train your body, and do the appropriate things for your age,” he said, “you can actually make even a 60-year-old human machine work very, very well.” Which means I have another 25 years to figure it out.