A couple of years ago, I wrote an article about the fine-grained nuances of interval training. According to Paul Laursen and Martin Buchheit’s telephone book of a text, , there are 12 distinct variables you can manipulate in order to tailor your workout to your precise physiological goals. Numerous flowcharts and sprawling decision trees guide you through the choices.

That’s great for some people and certain situations—but sometimes, instead of poring over a seemingly interminable menu, you just want to order the special. That’s the payoff promised by in the journal Sports Medicine, by a team led by triathlon coach and recent University of Toronto doctoral graduate (who’s now at Simon Fraser University). He and his colleagues crunched the data from 29 different studies to determine the best workouts to enhance endurance time trial performance. And believe it or not, they came up with an answer.

There have been numerous previous attempts to synthesize the research literature on interval training, but Rosenblat’s review sets some strict parameters. He only included studies that directly measured performance in a time trial, instead of looking at indirect measures like changes in VO2 max. The training programs had to last at least two weeks, and they fell into two categories: high-intensity interval training (HIIT) or sprint interval training (SIT).

Physiologically, the distinction between HIIT and SIT is that HIIT intervals are performed below your maximal aerobic power, which is basically the highest speed you hit in an incremental VO2 max test before you fall off the bike or the back of the treadmill. SIT intervals are performed above this power. Practically speaking, HIIT intervals tend to be one to five minutes each with a relatively short rest (more on that later) while SIT intervals tend to be 30 seconds or less each, pretty much as hard as you can go, with longer rest. Both approaches have been shown to improve time trial performance, but Rosenblat’s goal was to figure out how to fine-tune the details of each style of workout.

The 29 studies included in the analysis involved a total of 400 men and 91 women with an average age of 25, who were categorized as either inactive, active, or trained (meaning they were already following a structured exercise plan). The outcome measures were time trials in cycling, running, and rowing over distances from a mile to 40K.

First things first: training worked. As you’d guess, it worked better for previously inactive subjects, who got about six percent faster on average, than it did for trained subjects, who gained two percent. Once you take training status into account, other factors like sex, age, and baseline VO2 max didn’t make any difference. In the narrow parameters of the study (two or three workouts a week for two to ten weeks), HIIT and SIT seemed to work equally well, but via different mechanisms.

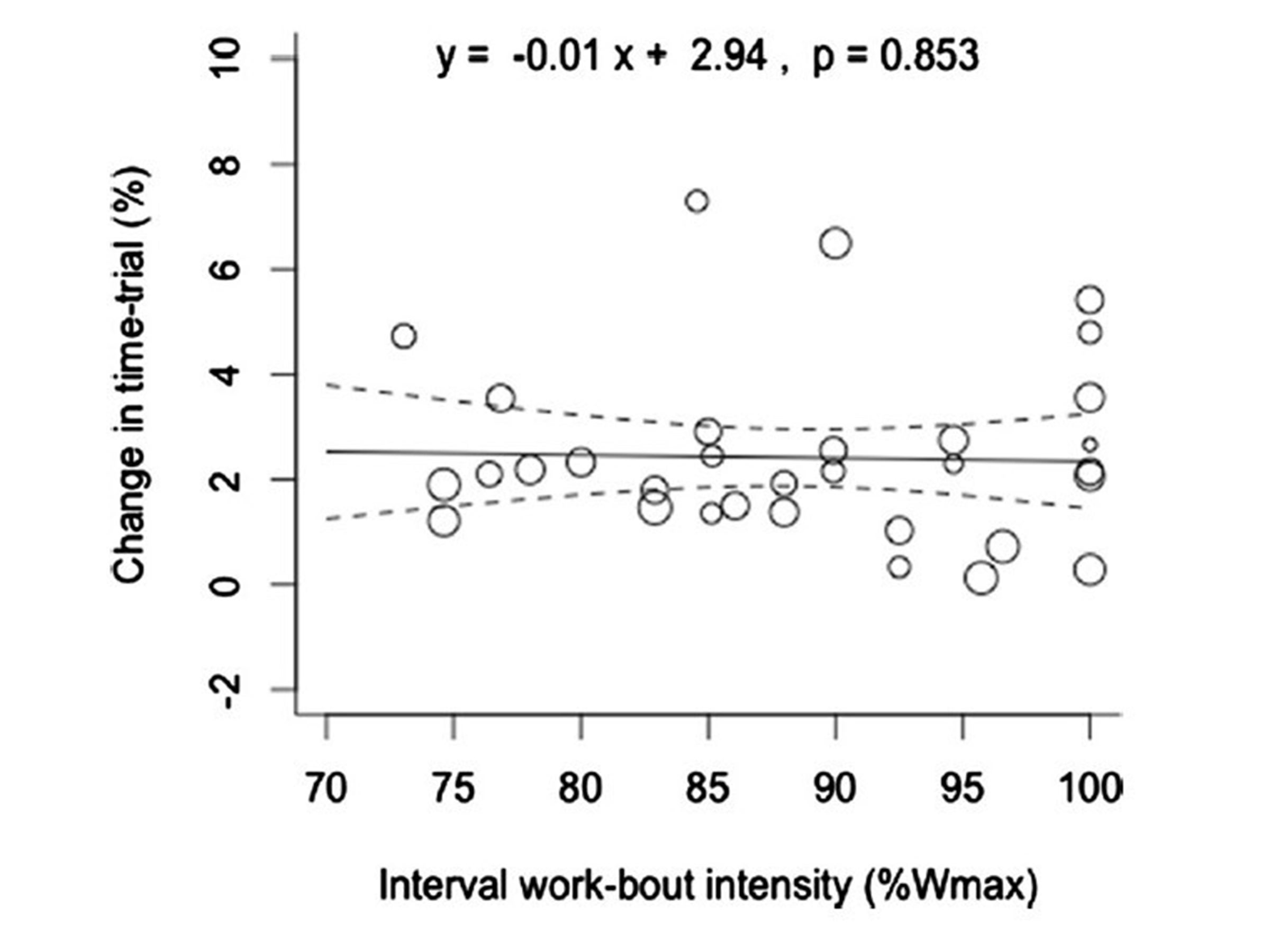

When you dig into the details, things get more interesting. For example, how hard should HIIT workouts be? The range could be anywhere from threshold pace to maximal aerobic power. The meta-analysis suggests the best pace is—well, it doesn’t actually matter. Here’s a graph showing time-trial improvement (on the vertical axis) as a function of interval intensity (on the horizontal axis, expressed as a percentage of maximal aerobic power, Wmax):

It’s a flat line: harder HIIT sessions produce basically the same gains as lower-intensity ones. There’s a caveat here: the higher-intensity sessions tend to be made up of shorter intervals lasting one to three minutes, while the lower-intensity sessions have longer intervals of three to five minutes. So it’s not that how hard you push doesn’t matter at all; it’s just that there’s no magic intensity. Within the parameters of a HIIT workout, you can get the stimulus you need by pushing harder during shorter intervals and not quite as hard during longer intervals—something that happens naturally. (For SIT, in contrast, it’s simple: sprint as hard as you can!)

There’s a more nuanced finding when you look at the effect of interval duration. Overall, duration had no effect on outcome for either HIIT or SIT. But when you narrow the search to studies including only trained participants, longer HIIT intervals produce better results than shorter ones. That’s not entirely surprising: it takes about two minutes for your oxygen delivery system to fully ramp up, so longer intervals force you to spend a higher proportion of your workout time at near max, and it’s consistent with (though ) previous findings.

Rosenblat sifts through plenty of other details. Increasing the recovery between HIIT intervals from one to two minutes allows runners to maintain a faster pace, but further increasing it to four minutes doesn’t add much for trained athletes. The number of SIT reps you do doesn’t matter; doing more than five HIIT reps seems to be counterproductive, but that’s probably connected to the fact that, as noted in the previous paragraph, longer intervals (which you generally do fewer of) are more effective.

And so on and so on: we’re drifting back into the morass of Laursen and Buchheit’s 12 variables. But if you just want to order the special, here’s what Rosenblat and his colleagues recommend. You want a good, evidence-based HIIT workout to make you faster in races? Do five x 5:00 with 2:30 recovery, twice a week, for at least four weeks. You want to sprint instead? Do four x 30 seconds with 4:00 recovery, twice a week for at least two weeks. That, according to the meta-analysis, is what the data suggests.

There are some caveats. In fact, to their credit, Rosenblat and his colleagues include a full page of them in their paper. One of the key ones, in my view, is that the studies involved all HIIT or all SIT rather than a mix of the two. What would happen if you had a group of runners do one HIIT session and one SIT session per week, in order to harness two different routes to improvement? Maybe five x 1600m with 2:30 rest, and eight times a 30-second hill sprint with walk-down recovery. Fill in the gaps with some long easy runs and perhaps a threshold workout, and you’ve got a program whose bones look an awful lot like the weekly routines I’ve encountered in successful training groups around the world. When the word of mouth is , you might not even need to read the menu.

For more Sweat Science, join me on and , sign up for the , and check out my book .