Just before Christmas, social-fitness platform Strava released its annual , a look at how people used the service to record their workouts in 2020.��Because Strava has millions of active members, it’s always an interesting perspective. But this year, COVID-19 shaped the data in remarkable ways.

By now��you probably know that the pandemic created a huge exercise boom in the U.S., with bikes at its center. New bicycles have been in short supply for months, and some shops have��entirely sold out. We’ve been left wondering whether this was just another 2020 fad, or if it will lead to lasting change. Strava’s report, and broad sales figures from the NPD Group, which tracks data across thousands of American��bike shops, suggests an answer: cycling’s newfound popularity might endure.

Where Activity��Boomed, Where It��Didn’t, and Why

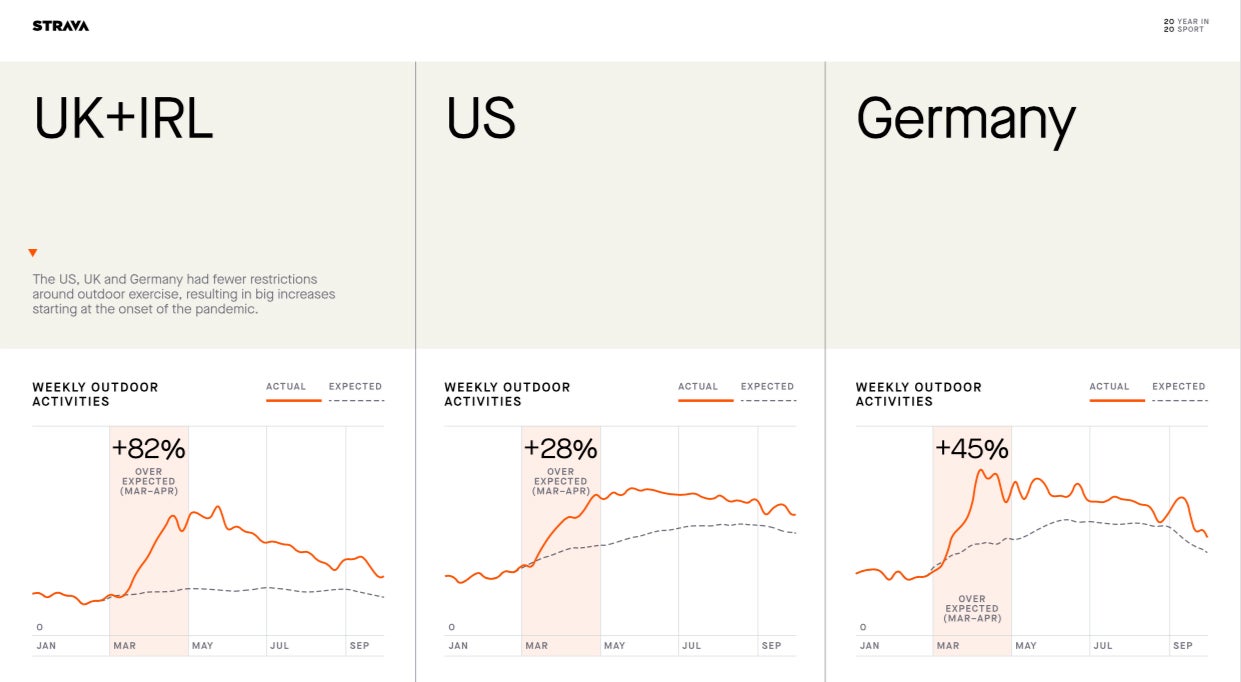

One of the most striking pieces of information revealed in��Strava’s report was the variation of residents’ activity levels in different countries. Last spring, during initial COVID lockdowns, nations��like Spain and Italy largely forbid most people from going outside. Predictably, even as indoor Strava activities such as��trainer rides and treadmill runs��jumped in those countries, outdoor activities—at least those posted to Strava—plummeted by roughly 66 percent compared to normal times. Meanwhile, in countries that permitted outdoor exercise during lockdown, like the U.S., Germany, and the United Kingdom, Strava activities markedly increased (up 28 percent in the U.S., 45 percent in Germany, and a whopping 82 percent in the UK).

After the lockdowns lifted, something strange happened. In heavily locked-down countries, Strava��activity predictably zoomed to high levels, then sputtered and stalled out at or below the normal��trend line. In countries that experienced more lenient lockdowns, ridership ebbed a bit but stayed persistently higher than the expected average.

According to Simon Marshall, a sports psychologist and former associate professor at the University of California at San Diego, the science of how we form habits offers some insight. “As you rebound from being cooped up, you’re desperate to get out there,” he says. Marshall compares the phenomenon to New Year’s resolution patterns. “We always go over the top on how much we can do, and those habits are not sustainable,” he says. What’s more,��habits typically take around eight weeks to form. As the context of our daily life changes,��“we almost have to relearn our habits again,” Marshall��says.

Unsurprisingly, the Strava activity data for hard-lockdown countries is all over the place, with quick spikes followed by equally fast downturns, while the U.S. saw much more sustained growth. Marshall attributes this to people in locked-down countries whipsawing through periods of activity and rest as they��tried to find an exercise equilibrium. (This is not to suggest lockdowns were a bad idea; they were—and remain—an essential tool��to fight the pandemic.) Meanwhile, in the U.S., since cyclists could still ride outside, they could more reliably form new cycling habits.

Which Bike Markets��Boomed, and When

According to Dirk Sorenson, executive director of the NPD Group’s sports division, sales of home-fitness gear thrived during the height of the initial COVID lockdowns. But the increased interest in cycling gear and the historic sales boom that followed in this country were��like nothing Sorenson had ever seen before. “It’s unabated,” he says.��“Just crazy interest, and it does not seem to be really slowing.”

Interest in Casual Bikes Shot��Up First��

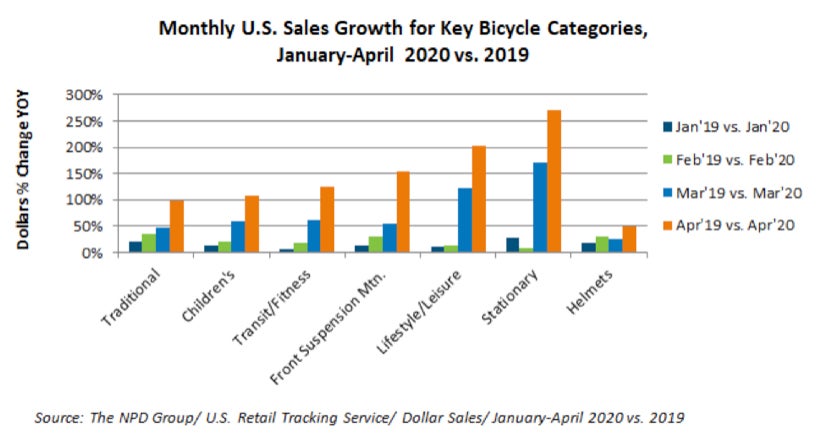

In the initial months of the pandemic, demand was driven by what Sorenson calls family riding. Casual, fitness, and children’s bikes flew off shelves. The months of March and April were��when things really started to surge. Sales of kids’ bikes increased��100 percent, fitness bikes went up 125 percent, and lifestyle bikes like beach cruisers escalated��by��a whopping 200 percent year over year from April 2019. As Rod Judd of PeopleForBikes��told ���ϳԹ��� last spring, “Anything under $600 is just flying out.”

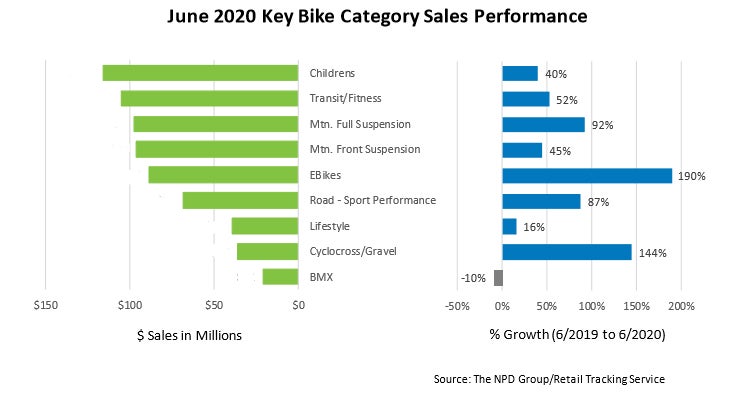

Then Enthusiast Bikes Started Selling Fast

Just as the jump in casual categories began to fade, higher-priced enthusiast categories started to surge. Gravel was already one of the hottest segments for the bike industry, but the pandemic supercharged it, with sales jumping 144 percent in June 2020 compared to 2019. August and October saw��94 percent and 110 percent year-over-year increases, respectively. Mountain bikes and urban/fitness bikes,��which saw double-digit increases in June, were up 116 and 126 percent��year over year, respectively.

Amid all this ebb and flow, one category stayed strong: electric-assist bikes, the sales of which��were up 190 percent in June year over year, 142 percent in August, and then 179 percent in October. “What you’re seeing is the maturation of the e-bike market,” said Sorenson. The technology is far more sophisticated than it was a decade ago, and prices on midrange bikes are dropping. There’s also far more variety today—and not just in e-bikes. Whether it’s an e-commuter or a versatile gravel quiver killer, the bike industry is meeting a lot more needs, a lot more specifically, than it used to.

Indoor Cycling Became More Popular

Along with e-bikes, stationary/indoor riding led the boom, as people scrambled for socially distant workout options during lockdown. Sales of indoor bikes and trainers jumped 275 percent in April 2020, year over year. “Typically, you see products like trainers decline as summer emerges,” says Sorenson. Not this time around. When the COVID spring hit, companies like��Saris, Stages, Tacx, and Wahoo��didn’t have peak levels of inventory��and quickly sold out. Many models are still listed as out of stock until February—at the earliest.

Where’s This Trend��Headed?

At this point, your big question is��probably: When can I buy a damn bike again?

The data Sorenson looks at shows little sign of the boom slowing, although it may naturally ebb in��the��winter. One major unknown that impacts the future is how big 2020 sales would have been had everyone who wanted a bike been able to buy one. Some shops sold out of entire product lines in the spring, and many customers who missed out preordered for later delivery. “We’re in that phase now where retailers are restocking, but in many categories, as soon as a bike hits the floor, it goes away,” Sorenson��says. If those would-be buyers are patient, the sales boom could continue on a similar trajectory.

Blair Clark, president of Canyon’s U.S. division, thinks the surge is durable. “Two big trends we see are people who either returned to the sport or discovered it for the first time and are really falling in love with it, paired with a constantly growing adoption of the bicycle as transportation,” he says. Americans, he adds, “are finally waking up to the transformative power of bikes for transportation, not just recreation.”

Indeed, Sorensen says that utility bikes may see sustained growth. As workers return to offices, they may still feel most comfortable with socially distant commutes rather than public transit. In general, he expects more add-on sales from those new riders. “How big, I don’t know,” he says. “But I don’t think it’s going to go back below where it was in 2020.”

So when can you buy a bike again? It’s possible to snag one now, but you’ll be in for a search. An unusually high number of 2021 models are already sold out online and may be hard to find in stores as well. Bike makers have tried to adjust production upward, but that’s not easy, in part because production quotas are set many months in advance, and because building complete bikes requires a plethora of parts that come from companies that may or may not also be impacted. “We’ve increased forecasts with our suppliers to bring in a record amount of inventory,” says Nick Hage, general manager for Dorel’s Cycling Sports Group (CSG) North America, which owns Cannondale and GT, among other brands. “But that doesn’t mean there won’t be supply-chain challenges.”

Most bike brands don’t own their own frame factories; they contract with producers in Taiwan��and mainland China. (Notably, Giant does own some factories.) These facilities��, which means companies are competing for additional capacity in the same facilities. They’re also competing for parts, like drivetrains and wheels, from other partners. “Obviously, we ran into difficulties when other brands began to ramp up their sourcing and production-line requests at the same time,” says Canyon’s Clark. He adds that Canyon prioritized production bumps in areas where it struggled to meet consumer demand in 2020, like gravel and e-bikes.��

The bottom line, according to CSG’s Hage: even though brands are working hard to increase supply, “there will be shortages in certain categories and models next year. We won’t see ‘normal’ until we get into 2022.”

On the plus side, there are a lot of new friends to ride with.