This is an article about saunas and post-exercise recovery. But it’s also a parable about sports science, the perpetual search for a new edge, and (not to be too grandiose about it) life itself. The moral of the story is pretty simple: there’s no free lunch.

Over the last few years, I’ve written about a bunch of different lines of research suggesting that heat could be a secret training weapon, as summed up in this trend piece. Thanks to the hot temperatures expected at this summer’s Olympics in Tokyo, as well as other hot-weather sporting championships like last summer’s track and field world championships and the 2022 World Cup, both in Qatar, there has been a big surge of heat-related sports science studies.

The potential benefits are varied. For athletes, it’s been known for a long time that heat exposure over the course a few weeks—training in heat, living in a hot place, or even just hitting the sauna or after workouts—helps prepare you to perform better in hot conditions. More recently, there’s been some evidence that the same heat protocols might produce adaptations like enhanced plasma volume that boost your endurance even in normal or cool conditions. There have also been hints that heat exposure might have other beneficial effects on stress hormones, blood circulation, immune functions, and pretty much anything you can think of.

When anything starts getting that much hype, you know the backlash is coming. One form of backlash is to say that heat . But published in the International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance takes things a step further, suggesting that post-exercise sauna exposure can actually hurt your recovery and subsequent performance. On reflection, this shouldn’t be a surprise—but as someone who has written about heat’s potential benefits numerous times, I have to admit that it’s a message I’ve generally glossed over or omitted entirely.

The new study comes from a group led by Sabrina Skorksi of Saarland University in Germany, working also with researchers at Johannes-Gutenberg University and Ruhr University Bochum. They recruited 20 swimmers and triathletes, all competing at the national level or higher, to do a two-part protocol. In the afternoon of day one, they swam a performance test—4 x 50 meters all-out with 30 seconds of rest—then did a regular hard workout followed by one of two recovery protocols. The next morning, they swam the 4 x 50m test again.

They did this two-day protocol twice, in randomized order, once with a post-workout sauna and the other time with a placebo recovery. The sauna was 3 x 8-minute��bouts at 176 to 185 degrees Fahrenheit (80 to 85 degrees��C) and 10 percent humidity, with five minutes at room temperature between bouts. The placebo involved sitting passively for 35 minutes while applying a special recovery oil (which was really just plain massage oil) to their bodies.

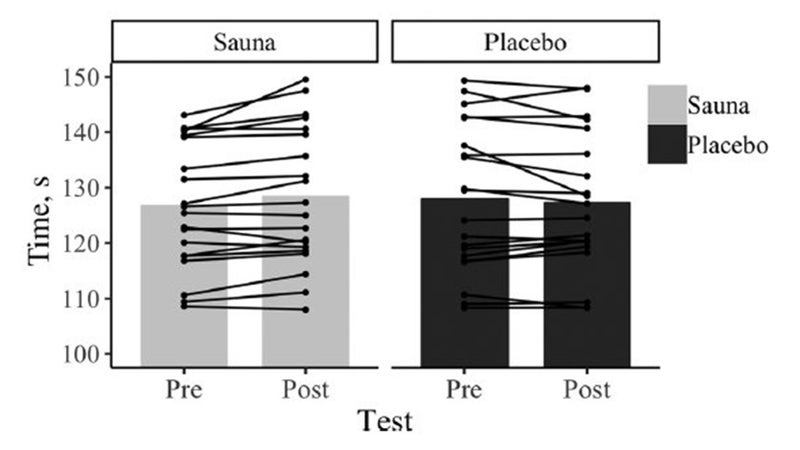

Here are the overall and individual results for total swimming time in the performance test, showing that times were a bit slower after the sauna and similar or perhaps quicker after the placebo. Note that each swimmer swam in their preferred stroke, so some of the slower times are from breaststrokers:

On average, the swimmers got 0.7 percent faster the morning after using recovery oil, but got 1.7 percent slower the morning after having a sauna. In particular, there was a statistically significant difference in how fast they swam the first 50-meter��rep. Their overall stress levels, as reported in a pre-workout psychological questionnaire, were also slightly higher the morning after the sauna compared to morning after the placebo, indicating that they felt a little less recovered.

There’s a long discussion in the paper of why the sauna might have negative effects, including strain on the circulatory system, activation of the sympathetic nervous system, neurohormonal stress as indicated by cortisol release, and so on. The basic summary is that they don’t know, although it’s probably safe to rule out dehydration, since the subjects had to drink 1.5 liters (50 ounces) of water during the sauna and the same amount again in the subsequent two hours. But in a broad, hand-waving way, we can make the assumption that sitting in a very hot sauna imposes a physiological stress, and it’s not that surprising that this additional stress might interfere with recovery from the stress of the workout.

The stress imposed by heat isn’t an unfortunate side effect. It’s precisely the point of heat training: adding a particular type of stress to elicit adaptations in the body. The fact that you can experience this stress while lounging in the sauna doesn’t mean it’s cost-free. Nor does it mean that saunas, or heat in general, are “bad.” It simply means that adding heat increases your training load unless you slow down or reduce your mileage to compensate. And it��also means that, just as with fasted workouts and altitude tents and pretty much any other training adjunct you can think of, you don’t get something for nothing.

My recent book, , with a foreword by Malcolm Gladwell, is now available. For more, join me on and , and sign up for the Sweat Science .