Abstention is a very controversial topic—and yes, I’m talking about sports science here. You’re gearing up for an important race, and hoping to get the biggest performance-boosting jolt possible from your race-day caffeine. Should you deny yourself coffee for a week or so leading up to the race, so that you’re in a state of heightened caffeine sensitivity?

That’s a fairly common routine among elite endurance athletes, but definitely not a well-loved one. I once attended a sports nutrition panel where Des Linden talked about this part of her pre-race routine. This is a woman who (along with fellow elite runner Ben True) owns her own coffee company, . She doesn’t swear off coffee lightly, and you could hear the angst in her voice as she described how that coffee-free week felt to her. But hey, anything for an edge, right?

The trouble is that the scientific research into the supposed benefits of abstention has been murky and inconclusive at best. A number of studies have looked for an effect, but none have been particularly convincing. The , two years ago, involved 40 well-trained cyclists, and found no difference in the size of the boost the riders got from caffeine whether they were low, medium, or high caffeine consumers normally. This argues against any big habituation effect that dulls caffeine’s benefits with regular use.

Still, it’s very hard to pick up subtle differences in this sort of study, given that variations in individual performance are so large. To get a better handle on the question, you’d need to do some sort of crazy study that involved testing the same people over and over and over and over as they gradually habituated to caffeine. And that, as it happens, is exactly what in PLoS ONE does.

A team of researchers from Camilo José Cela University in Spain, led by Juan Del Coso, put a group of 11 volunteers through a pair of grueling 20-day protocols. All the volunteers were normally light caffeine users, consuming less than 50 mg per day, much less than the in a typical cup of coffee. For one of the 20-day protocols, they took a daily pill containing 3 mg of caffeine per kilogram of body weight, a relatively standard dose used by athletes for performance enhancement that works out to about 200 mg per day. For the other 20-day protocol, they were given a daily placebo. The two protocols were separated by seven days, with the order determined randomly and concealed from the subjects.

Before and after the study, and three times a week during the study, they completed a VO2max test to exhaustion and a 15-second all-out sprint on an exercise bike. This allowed the researchers to track exactly how the performance edge from caffeine changed as the subjects gradually got used to taking caffeine each day, and compare that to exactly the same progression when they got placebos instead.

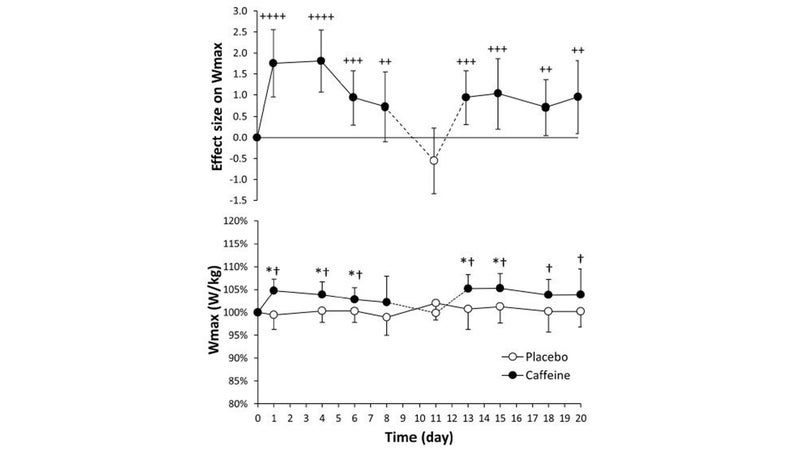

Here’s what that data looks like for the peak power (Wmax) the volunteers reached in their VO2max tests before reaching exhaustion (caffeine is the black circles, placebo is the white circles):

The bottom graph shows the actual power data. You can see that as soon as they start taking caffeine for the first time, on day 1, they immediately get a roughly 5 percent boost in peak power compared to the placebo. The top graph shows the effect size, which is a measure of how big the difference between caffeine and placebo is relative to the error bars. The boost for the first few days is considered a large effect size.

But then things start to tail off. In fact, on day 11, the effect size drops to about zero. This is a good thing, because day 11 in the study was a manipulation check. Instead of taking a pill and then getting on the bike 45 minutes later, as they did most days, they took their pill after the bike tests. So they were still getting their caffeine dose as part of the habituation process, but they didn’t get any performance boost during the tests. So the results of the caffeine and placebo should be roughly the same that day—which is exactly what you see.

If you look at the other results from the study, you see similar patterns for VO2max and for the 15-second sprint power. The subjects get a big boost from caffeine in the first few days, then it starts to taper off, but it never gets to zero. In fact, day 20 generally looks pretty similar to day 6. Based on these results, you might figure that caffeine tolerance (at least at the doses tested here) never completely takes away the benefits of a caffeine boost. But it does, perhaps, rob you of a little bit of the edge you’d otherwise get. That’s probably a mixed blessing for Linden and co., because it suggests that a pre-race caffeine detox, no matter how painful, might be worthwhile after all if you’re truly chasing every second.

Of course, performance is a complicated equation. For some people, swearing off caffeine would make race week so miserable that they’d probably lose more than they gain. And there’s also some emerging genetic research suggesting that some people don’t actually get a performance boost from caffeine anyway. But perhaps the biggest remaining question is the opposite of the one that this study tackled: how many days of caffeine abstention does it take for caffeine addicts to get their full boost back? It’s a pressing practical question. But good luck recruiting subjects to answer it.

My new book, , with a foreword by Malcolm Gladwell, is now available. For more, join me on and , and sign up for the Sweat Science .