Hundreds of climbers are streaming into Nepal and Tibet this week as the spring climbing season on Mount Everest begins. The stories to watch this year include an attempt at the first new route on the mountain╠řin a decade, ominous weather indicators, shifts in whoÔÇÖs climbing the worldÔÇÖs highest mountain, a potentially record year for summits, and more. HereÔÇÖs what you need to know.

Climbers to Watch

There could be more than 1,000 climbers, including support crews, on Everest this spring. Most will follow the standard╠řSoutheast Ridge╠řfrom Nepal or the Northeast Ridge from Tibet, but a few will follow their own path.

National Geographic╠řphotographer Cory Richards and Ecuadoran climber╠řEsteban ÔÇťTopoÔÇŁ Mena, veteran climbers with six previous Everest summits between them, will attempt to complete the first new route to the summit in ten╠řyears. ItÔÇÖs a natural line on the North Face that has been attempted but never completed, going up 6,500 feet from advanced base camp╠řto the Northeast Ridge.

The last time a new route was completed on Everest was the Korean line on the left side of the southwest face (southwest face to West Ridge) in 2009.

Richards and Mena arenÔÇÖt the only climbers who should be on your radar this year.

Kami Rita Sherpa is going for a record 23rd summit. Nirmal Purja Sherpa will try to summit all 14╠řof the╠ř8,000-meter mountains in seven months, starting with Everest;╠řif he does, it will╠řshatter the current record of seven years╠ř11 months╠řand 14 days, held by Chang-Ho Kim of South Korea. Two female Sherpas, Nima Doma Sherpa╠řand Furdiki Sherpa, are attempting to summit in honor of their husbands who recently died on the mountain. South Korean Hong Sung Taek will attempt a new route on the south face of Lhotse for the fifth time.

Crowd Control Is Getting Better

With this many people on the mountain,╠řwill crowding be an issue? In past years, there have been delays on the mountain because of long lines at the usual spotsÔÇöthe Second Step, on the Tibet side, and the place where the Hillary Step used to be, on the Nepal side. Even with ladders, these two difficult spots slow teams down.

However, donÔÇÖt expect to see significant delays like there were╠řin 2006 and 2012, despite a record number of climbers. Why? The Everest climbing community has become better at managing crowds. Guides coordinate better among themselves, and improved weather forecasting allows teams to better prepare for their summit bids.

Individual expedition leaders are stopping people who canÔÇÖt make it and create a bottleneck with their slow pace. Many teams have switched to earlier starting times for slower members. Another recent trend is using supplemental oxygen at six╠řliters per minute╠řinstead of the traditional two╠řor four liters per minute, which helps increase the speed of many climbers.

Even with improved management, problems will quickly stack up if poor weather delays the opportunity to summit.

A nightmare scenario occurred in 2012 when harsh weather shut down rope-fixing teams and summit attempts for weeks on end. There were only four days suitable for a safe summit attempt instead of the average 11 days. When teams were brave or frustrated enough to go for the top as time was running out, they experienced horrible delays.

Last year was the opposite. Climbers experienced an unprecedented window of 11 straight days with safe summit weather, enabling to reach the top. Everyone is hoping for a repeat of 2018, but there are warning signs╠řit might not happen.

The Weather Could Be Worse Than Usual╠ř

This is always the wild card in anticipating big-mountain climbing issues. K2 and Nanga Parbat experienced constant high winds and deep snow this winter, and there are indicators that climbers on Everest and Lhotse should heed.

Nepal has had more snow than any year since 1975. Kathmandu might be the canary in the coal mineÔÇöthe Nepalese capital reported snow on February 28, the first time that has happened since February 14, 2007 (and before that it hadnÔÇÖt snowed in the city in 63 years).

India saw a 24 percent increase in rainfall this winter.╠řAfter IndiaÔÇÖs last rainy winter, in 2013, rope-fixing teams on both sides of Everest were delayed until May 17, instead of getting to the summit by late April.

Only once╠řin the last 24 years, 2005, did India receive more rainfall than it did this winter. No climbers reached the top until May 21 that year, the latest summit date since Tenzing Norgay Sherpa and Edmund Hillary completed the first ascent, on May 29, 1953.

How this winterÔÇÖs weather will affect conditions on Everest is unknown. The first clue will come when the rope-fixing teams reach the North and South Cols in early April. If it looks like a season with bad weather and few summit days, smart teams will push hard to get their acclimatization in as soon as possible and be in a position to take advantage of any summit window that emerges in May.

More Climbers Are Coming from China and India

Mountain climbing continues to attract new fans, increasing traffic on the worldÔÇÖs biggest peaks and providing more business for guide services. Keeping with recent trends, middle-class climbers from China and India are coming to Everest in droves, mostly to the Nepal side.

Fearing runaway crowds and the risks that come with them, China has enacted perhaps the strictest requirements of any country with a high or╠řfamous peak.

If you are a Chinese national, you must have summited an 8,000-meter peak before attempting Everest from the Tibet side. China will only issue 300 climbing permits this year.

Those restrictions are one reason the operators in Nepal are guiding more and more Chinese climbers each year. Nepalese╠řguides have also focused on this lucrative market because Chinese clients appear to be less sensitive to high╠řprices compared to other nationalities.

The number of teams from India is╠řgrowing rapidly, too. Transcend ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°s has guided more than 60 young Indian climbers to the summit of Everest in recent years. The Indian army is back with its╠řusual team of 20 to 30 members, plus support. ItÔÇÖs one of the larger teams and has╠řtraditionally moved slowly and created delays.

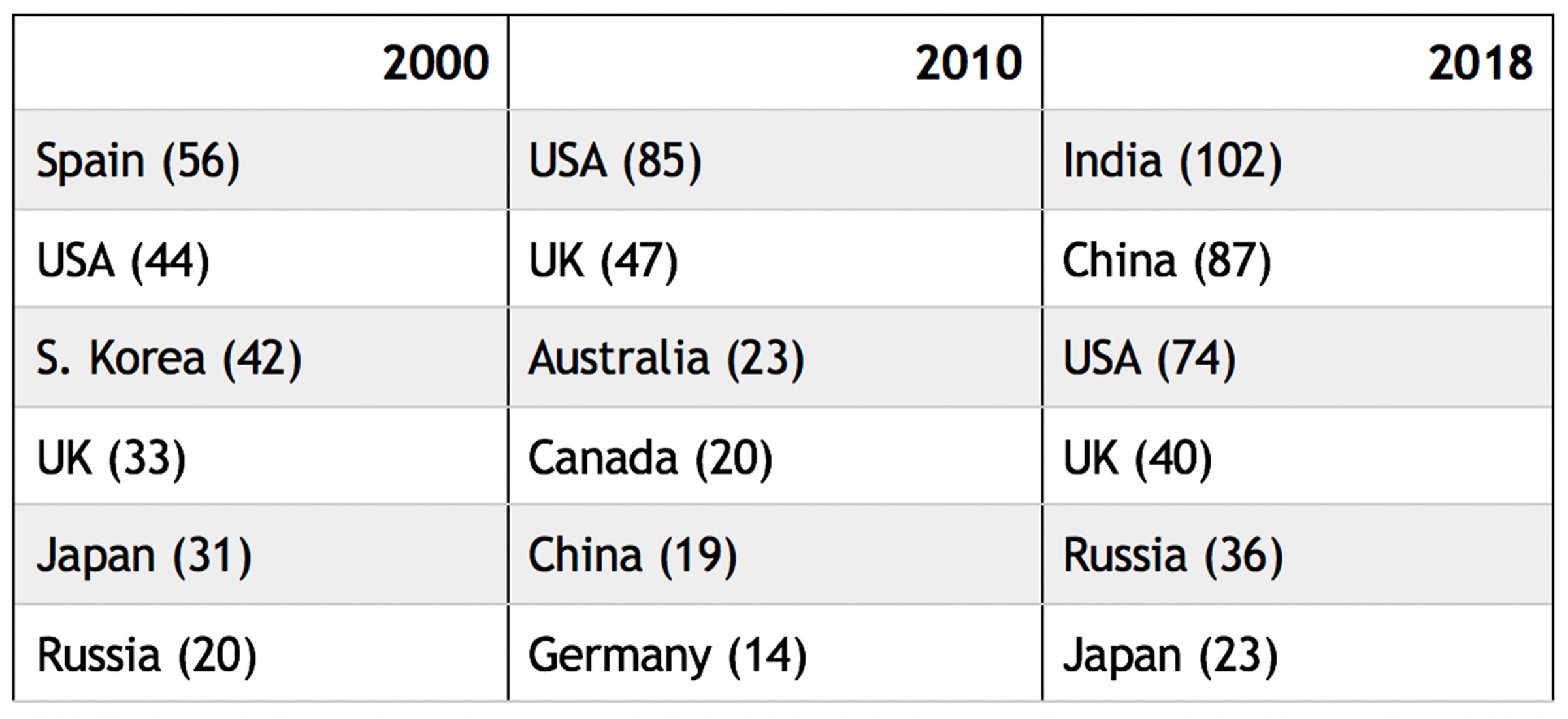

The number of climbers from countries that fueled the Everest explosion in the last 20 years is declining. Climbers from Western Europe, the United States, Australia, and Japan are slowly becoming the minority among those attempting to summit the mountain.

Top Nationalities Above Base Camp

ThereÔÇÖs a Lack of Qualified Sherpas for Support

One potential issue for the growing number of climbers╠řis a lack of qualified Sherpas to support them.

It has almost become the norm for each climber to have a personal Sherpa from Base Camp to the summit. However, there are not enough Sherpas or Tibetans to pair with every individual climber. This could be a disaster waiting to happen.

A lack of qualified support-team members makes it more difficult to handle a large number of emergencies, which could occur if operators are pressured to get their clients to the summit and attempt to push through difficult weather. If there are more emergencies and not enough people to help, it could be an inflection point in the popular lure of Everest.

Rescue Companies Are Watching for Scammers

Finally, thereÔÇÖs been a lot of press about scams involving guides, helicopter companies, and hospitals cheating evacuation companies and insurers out of hundreds of thousands of dollars with fake or duplicate rescue claims. Several insurance companies even considered dropping travel insurance for Nepal, .

After an inquiry, the Nepalese government promised changes, but nothing of substance has occurred. Despite this, some of the longtime evacuation companies wonÔÇÖt let the issue alter their professional approach to serving clients and are taking precautions to prevent fraud.