One of the endearingly nerdy things about the recently retired runner Mebrahtom “Meb” Keflezighi is that he ran 26 competitive marathons in his career—one for each mile of the race. (He also retired at age 42, which he once said seemed like an appropriate age to stop since the marathon has 42 kilometers.)

��

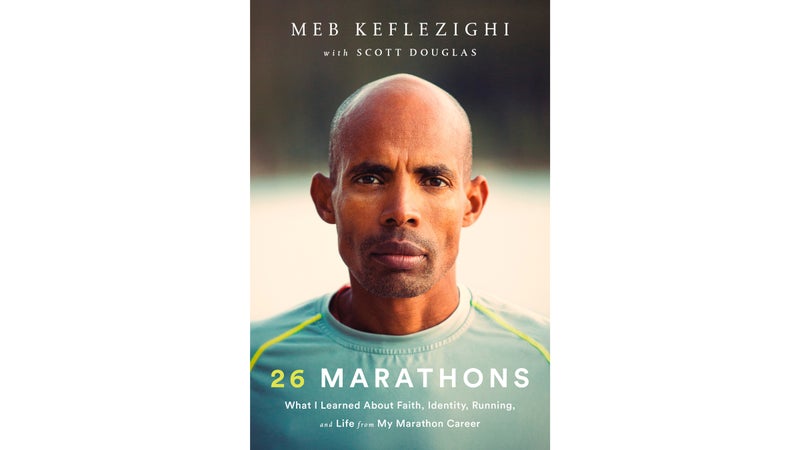

Now, in collaboration with Runner’s World contributing writer , Meb has published a memoir in which each chapter contains a short synopsis and “Key Lesson” of every marathon he raced from 2002 to 2017. Out today, 26 Marathons recounts the triumphs and disappointments of one of the legends of American distance running.

��

With this year’s race just around the corner, we’ve excerpted a section from the chapter where Meb’s recounts his first time racing the Boston Marathon.

MARATHON # 7��

2006 BOSTON MARATHON APRIL 17, 2006��

Place: 3rd��

Time 2:09:56��

Key Lesson: The marathon is a metaphor for life in how it rewards patience.

I may have been the fittest I ever was when I ran Boston in 2006. Winning Boston was both a lifetime dream and a reasonable goal, given my fitness, accomplishments, and experience. I was also now a father to our daughter Sara. Being a provider added motivation and purpose to my running.��

I’d been told Boston is tough to win in your first attempt. But I wanted to go for it. Running to win is my nature. I was fit, highly motivated, and ready to draw on experts’ advice on the course. To win races at the highest level, you’re always responding to or initiating moves that whittle down the pack until one runner is left in front. So when the race began and the frontrunners went to a fast early pace, I had to go with them if I wanted to fight for a victory.��

What I didn’t have to do was help push the pace. That was my mistake in my first Boston. It’s the same mistake so many people make there. You feel so good, and the first half is primarily flat or downhill, and the crowds are amazing, and it’s the Boston Marathon, and . . . well, it’s easy to get carried away.��

It wasn’t until we reached the halfway point that I saw our total running time. Have I mentioned how good I felt? We hit the 13.1-mile mark in 1:02:43, or mid-2:05 marathon pace. The Boston course record at the time was 2:07:15. The world record was 2:04:55. My personal best was 2:09:53. I thought, “Well, I can’t do anything about what I’ve done the last 13.1 miles. It’s either going to be a great day where I cut two or three minutes off my PR, or it’s going to be a long day. Be ready for either.”��

I was alone in third place, struggling to get through the hardest part of the course on legs that were shot from the classic Boston unforced error—too fast too soon.

It was the latter. When we hit the Newton hills, I hit the Wall. I was alone in third place, struggling to get through the hardest part of the course on legs that were shot from the classic Boston unforced error—too fast too soon. In any marathon, but especially at Boston, for every seeming advantage you gain in the early miles by running too fast, you pay back with interest over the final miles.��

The crowd is what got me through the closing miles. They ��kept cheering “Go, Meb!” or “USA! USA!” I drew energy from that and was able to hold on for third place despite having to dig really deep to keep going. Up ahead, Cheruiyot passed Maiyo and won in 2:07:14, one second under the old course record.��

I took a little satisfaction in contributing to the record being broken. I took more satisfaction from my time of 2:09:56. It was the same time I’d run in New York the previous fall, and only three seconds slower than my personal best.. If you race frequently, at any level, you should be able to be just as consistent. If you put in the work and stay healthy, you’re the same person from one race to the next. Sure, there will be variations because of weather or tough courses or an off day. But overall, in running and life, most of your performances should be in the thick part of the bell curve.��

I never had a bad race. My results weren’t always what I wanted, but each was a learning experience—for racing and life. You usually learn more from setbacks, such as being aggressive too early in a marathon, than from once-in-a-lifetime days.��

��

After finishing third despite making a huge error, I knew how I could win Boston someday. For starters, don’t run the first half in 1:02! I learned the hard way that no matter how great you feel early on, you have to save something for the hills. Rather than beat up on myself, I filed that lesson away. I never stopped believing that one day I’d have a chance to implement it.��

��

One way the marathon is different from other races is that its lessons often have parallels in the rest of life. The patience needed to master the marathon is a transferable skill. Taking the long view, putting in the unglamorous daily work, finding joy in the process, saving something for the inevitable challenges— these traits have helped me be a better husband, father, brother, and friend. The greatest rewards I’ve felt from all those roles in my life have come over the long term, not through immediate payoff.��

��

I left Boston that spring convinced I could someday win there. I already felt that way about New York City. But when I returned to New York in the fall, my patience was tested like it never had been in a marathon.

Adapted from Copyright © 2019 by Meb Keflezighi and Scott Douglas. Published by Rodale Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House.