A few months ago, I decided to collect all the plastic my household produced for 30 days by hoarding it in separate trash bags. I wanted to know what the impacts of an active lifestyle are on the waste stream. Our two-person, one-dog, highly active family reuses Ziplocs, avoids plastic bags when we shop (even while traveling), never buys overly packaged goods, and steers clear of the single-use produce bags you find in the grocery store. But one week in, I realized that the problem was bigger than I thought. On average, my home added three to five items per day to the pile of plastic.

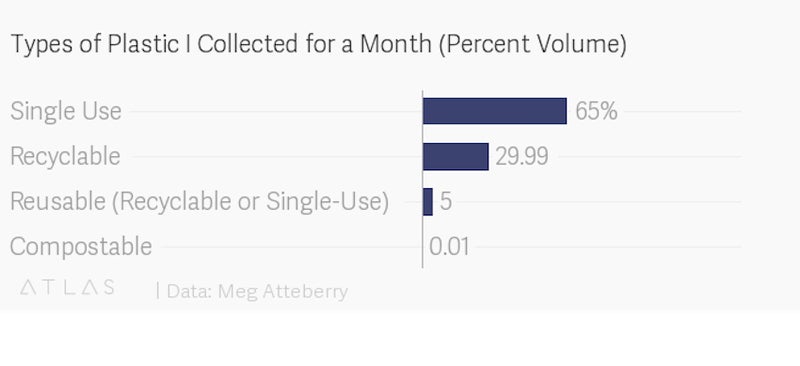

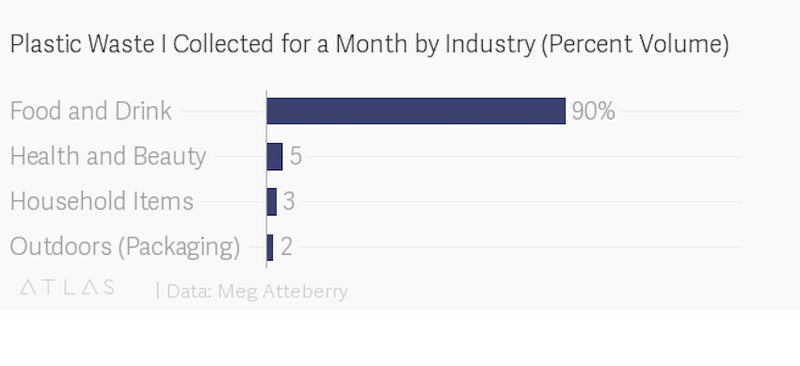

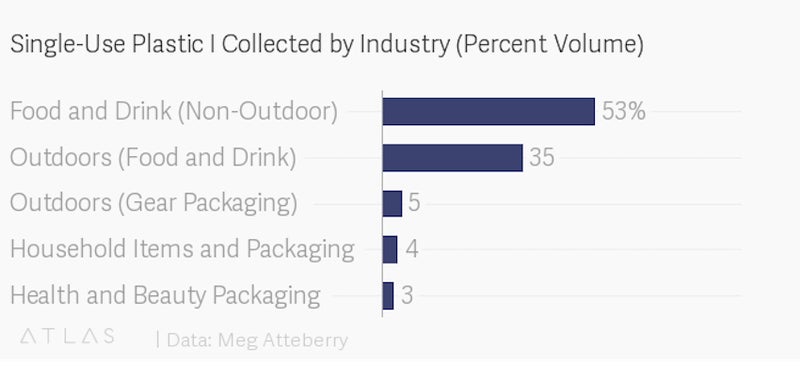

After the month was over, I sorted through the plastic IÔÇÖd collected. I felt sick that we filled two 13-gallon bags with waste. About 35 percent of the mountain was recyclable or reusable, primarily consisting of food containers, health care products, and a few broken household items.┬áAnd 65 percent was nonreusable, single-use plastic, a whopping 88 percent of which came from food products. I may be┬áa die-hard practitioner of Leave No Trace, but much of the plastic I collectedÔÇögranola bar wrappers, chip bags, polybags,┬áand moreÔÇöcould all be traced back to weekends in the wild.

I set out to learn how I could use less plastic outdoorsÔÇöespecially when┬ásnacking.┬áPlastic still reigns king for protecting food and maintaining shelf life, making it a go-to for plenty of instant meals or individually packaged snack foods. But Daniel Kurzrock, CEO and founder of ,┬áa company that creates meal bars from spent beer grains and wraps the bars in compostable film, says,┬áÔÇťNo one in the food business talks about how they are the future trash industry.ÔÇŁ

Kurzrock believes the issue involves the entire supply chain process, from raw materials to the consumer, and industries need to come together┬áto identify a solution. But heÔÇÖs quick to point out that compostable wrappers arenÔÇÖt a silver bullet. Yes, theyÔÇÖre petroleum-free compared to the typical film wrappers, but even they may end up in the landfill and not break down┬áproperly. ÔÇťAre compostable plastics the answer?ÔÇŁ Kurzrock asks. ÔÇťMaybe not. However, when we consider that they donÔÇÖt use petroleum like traditional wrappers, thatÔÇÖs still progress.ÔÇŁ

The only 9.1 percent┬áof U.S. plastic is actually recycled, compared to its more eco-friendly brother,┬áaluminum:┬á75 percent of all U.S. aluminum ever produced is . Because of its sustainability, several aquariums and zoos recently adopted products like , a business that markets┬áaluminum-bottled water so the products they sell better align with their message of conservation.┬áNicole Doucet, founder of Open Water,┬ásays theyÔÇÖd like to see the national parks join the movement, especially after the Trump administration reversed the ban on plastic-bottled water in many of AmericaÔÇÖs parks in 2017.

But┬áwhat about the plastics we canÔÇÖt see? Many people who adventure outside┬árely on synthetic materials┬áin our clothes and gear┬á(think: nylon, polyester, spandex, rubber, neoprene, and others). Those materials seep into our environment every time we step outside┬áin the form of microplastics.┬áThe Outdoor Industry Association (OIA)┬áflagged concerns as I tried to figure out how many micromaterials┬ámy household produced┬áduring my monthlong experiment. ÔÇťWe just donÔÇÖt know,ÔÇŁ says Beth Jensen, OIAÔÇÖs former director of sustainable business innovation. ÔÇťCurrently, we are working with both outdoor and fashion brands to develop standardized testing methods to determine how much shedding a particular synthetic product yields over its lifetime.ÔÇŁ

Abby Barrows, a microplastics expert and principal investigator for , aims to shed light on this issue. Barrows spearheaded the Gallatin Microplastics Initiative, a survey conducted in the remote Gallatin River, a headwater site for the Missouri River. More than 50 percent of the samples in these remote locations contained microplastic pollutants, many of which could be connected to outdoor recreation, like neoprene from kayakers and rubber from mountain bike tires.

ÔÇťT│ˇ▒ impact of microplastics is still under discovery,ÔÇŁ Barrows says.┬áÔÇťT│ˇ▒se micromaterials are ingested, even by large creatures like baleen whales. The buildup causes large blockages and lacerations that eventually kill the animal.ÔÇŁ

We know more about how many microplastics are released into the water when you wash these materials, but itÔÇÖs also believed that every time you go outside with them, theyÔÇÖre shedding some amount there as well. The problem is┬áwe donÔÇÖt know at what rate and how much is too much. ÔÇťWe donÔÇÖt know if these tiny pieces of plastic are leaching chemicals or how much they are bioaccumulating, and thatÔÇÖs scary,ÔÇŁ Barrows says.

The development of testing methods gives the industry a standard at which it can begin to control the problem, or at least bring consumer awareness to how their purchases affect the environment in ways they might not consider.

An ongoing study about microfiber shedding from the University of California, Santa Barbara () cited ways consumers can make a positive impact. One main takeaway was to wash synthetic materials less often, a simple solution for the dirt lover in all of us. The study also found that front-loading washing machines tend to make clothing shed seven times less than top loaders. (Front loaders also use less energy and 13 fewer gallons per load than their top-loading counterparts.)

My whole experiment left me disheartened. There was no ÔÇťahaÔÇŁ moment and no simple solution. Now┬áall I see are mountains of plastic waste everywhereÔÇöin the grocery aisles, infiltrating my home, at my favorite outdoor gear store. Not to mention the immense amount of plastic I canÔÇÖt see without a microscope that I shed simply by existing.

Despite that┬áhelpless feeling, my habits evolved. Every action we take outdoors has an impact on the environment. Now┬áI research the gear I buy before committing to a purchase. I replaced sandwich baggies with reusable, non-petroleum-based silicone versions. If I do end up with a single-use plastic baggie, I┬áreuse it until itÔÇÖs rendered useless. When I reach for that bag of chips on the way to the trailhead, I ask myself if the convenient snack is really worth filling the landfill┬áwith more plastic┬áand often opt for a homemade option instead.┬áWill I stop doing the things I love in hopes that my fleece sheds a little less on the environment? Probably not. But the small decisions add up.