The frustrating thing about reading Pam Houston is she does things no one else can pull off.

In memoirs, especially those that involve smushy, subjective things like relationships, nature, and relationships with nature, it’s nearly impossible to navigate the thin line between self-indulgent stories and ones that are very, very true.

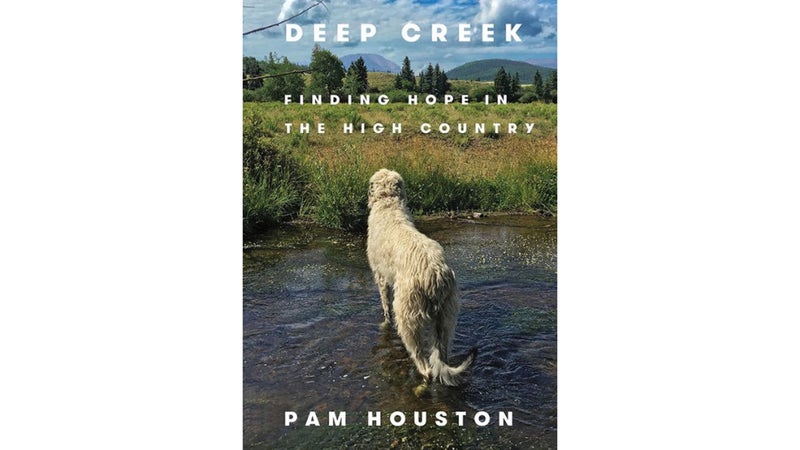

Since her 1992 breakout book of short stories, , Houston has mastered that honest margin. She’s earnest without tipping into schmaltzy, clear and vivid without becoming trite. Her new memoir, ($26; W.W. Norton), out last week, is no different. It’s ostensibly about her life on the 120-acre southern Colorado ranch she bought with the money she received for Cowboys—barely enough for 5 percent down—but it’s really about finding your identity by questioning your experiences.

The book weaves together stories of seasons on the ranch, where she finally discovers a sense of place, with the things threatening that stability: her troubled family history, her antsy need for adventure, the creep of climate change, and the writing work that both pays for the property and pulls her away from it. If you’ve read Houston’s fiction and nonfiction, which are tightly linked, many of the elements will feel familiar—abuse, the outdoors, addiction, risk, horses, and dogs. Her writing has always been personal, but Deep Creek is even more so. The people have names, her father’s sexual abuse is out in the open, she’s digging in.

The interlinked essays touch on disparate topics like narwhals and her childhood nanny, but they all tie back to the property. It’s the frame for understanding the toughness and flexibility it takes to struggle through building a life on a ranch, or really anywhere, and the feeling of being overwhelmed by the work and the knowledge necessary keep a fragile place going.

The main essays are bracketed by vignettes about ranch life, which are shorter and more concrete. These include the constant work of shoveling snow, the brain-expanding beauty of October in the Rockies, and taking the ram, Wooly Nelson, to get his horns sheared by shoving him in the back of a 4Runner and hoping he doesn’t bust out the back window.

Some sections lose the thread, like one where she repurposes the facts and old stories she learned from digging into the ranch archive—they feel less current and emotionally charged. Most feel more urgent than ever, like the chapter “Diary of a Fire,” about the 2013 West Fork Fire that almost torched her ranch. She digs into natural history, fire management, and the sleepless anxiety of being away from the place you love when it might be burning down. She calls the essay an “unironic ode to nature.”

The book is vivid and full of detail, real enough to feel relatable, even if you’re not going to put your life savings down on a remote ranch. Part of the appeal of Deep Creek is the hard-won fantasy that someone like Houston—nervy and green, but up for adventure—could carve out a life like that.

If you’re like a lot of people I know, trying to figure out where you want to live, what you want to love and be loved by, and where the lines are between adventure and home, no one writes about these themes more honestly than Houston. Deep Creek, her story of connection, and, as she says, learning to become the cowboy she thought she needed, is a model of what we might want—even if we could never pull it off like Houston does.