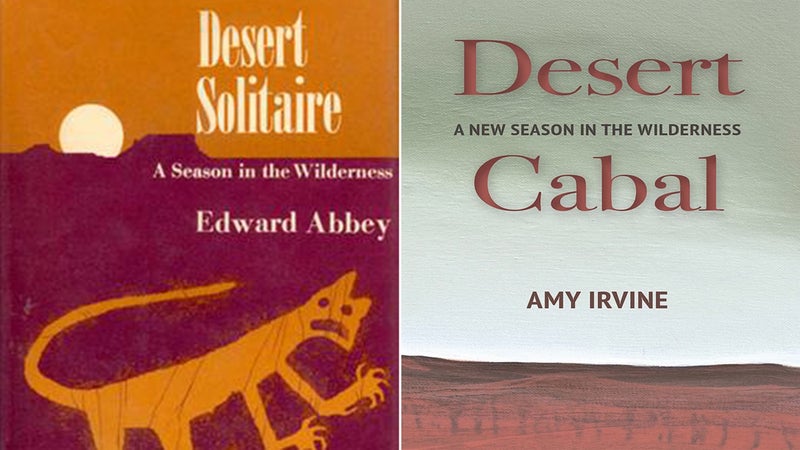

Edward Abbey wrote that part of love is anger, and Amy Irvine tries to untangle the two in her new book, Desert Cabal: A New Season in the Wilderness (Torrey House Press; $12). The book is a counternarrative to Desert Solitaire: A Season in the Wilderness, the cornerstone of Abbey’s canon, in which he observed humanity’s relationship with nature from his post as a ranger at Arches National Park. Abbey changed Irvine’s life, as he did for many people who feel drawn to the desert dirtbag life, but 50 years after Solitaire was first published, his vision of environmentalism feels narrow. So Irvine sits down in the desert, cracks a beer, and confronts Cactus Ed about his attitude.

Abbey’s self-claimed country, she says, is at risk for exactly the reasons he said it would be: greed, gasoline, and a gaping well of apathy. Preserving wilderness is even more important now than it was half a century ago, but the stakes aren’t as simple as he set them out to be. The resulting book has riled up some Abbey fans, but that’s exactly what makes it an important read.

In her imagined conversations with Abbey, Irvine is a little glib with the right-now references (talking to Ed about Twitter feels heavy-handed), but Desert Cabal is indeed a book for right now. She gets into the current rage brewing over public land and agency, the ties between women’s anger and environmentalism, and how we’ve chopped up land that once felt limitless. Her words are sharp, and they shed necessary light on how the country Abbey loved has changed.

But Irvine also acknowledges that there’s an ease to being angry like Abbey was, in a single, structural direction. And that rage isn’t afforded to people who don’t have his privilege.

Abbey treats everyone who isn’t him as the Other. He says people are the problem, without acknowledging that he, in fact, is a person. He minimizes tribes and women. Even fat dudes don’t pass muster, and forget about tourists, like the dead man he helps bring out of Grandview Point in Solitaire. That’s Irvine’s biggest beef. Abbey has become the standard bearer for a passionate wilderness ethic that values wildness over anything else, but we can’t operate the way he did, and we can’t rely on him to show us the way.

I read Irvine’s skinny 100-page book twice. And then, for the first time in a long while, I went back to my tattered copy of Desert Solitaire, which I stole from my college roommate when I was 19, living in northern Maine and trying to get to the desert, where I could be tougher and wilder. The fire and gleam of Abbey’s writing got up in my ribs. There’s a real romance in claiming wild country as your own and in the idea that to understand wilderness, you have to scratch through it with your fingernails like Abbey did, with a rope that’s too short. I wanted to see how much of my long-term love for the book was nostalgia.

Abbey’s writing is beautiful, but he lacks empathy, and that kind of callousness feels outdated now. He’s writing about womanizing and warm bodies, when in reality he had a wife and kids at home—a fact he never mentions in the book. He’s tossing Coors cans out the window of his truck with zero care for the landscape beyond his sphere of importance. That image of independence and disregard for the rules might sound romantic, but the littering and the lies feel self-centered now. There’s a disconnect between feeling and action.

Irvine feels the ache of how much the landscape has changed as well. She’s shaken by desert potholes scrimmed with sunscreen and Red Bull, and Jeeps ripping through cryptobiotic soil. But she’s jaded in a less individualistic way—Irvine knows it will take collaboration and political action to protect the landscape. “We have been emulating a misanthropic model that can breed intolerance and exclusion,” she writes. “The wilderness movement, like wilderness itself, should operate as a model of interdependence, not independence.” Irvine tells Abbey how the Trump administration has rolled back protections for clean air and water. Each of her chapters is a response to one of his, to check his reality and show that we can’t just monkeywrench our way back to untouched wilderness.

Fifty years of Abbey is a long game of telephone as his stories have been retold and mythologized. The canonical parts are baked into our brains and scrawled on T-shirts in Moab. The deeply racist diatribes are less so, as are the vainglorious anti-establishment rants, but in Desert Cabal, Irvine reminds us that they’re all there. And her retelling has drummed up another kind of anger.

Perhaps because Abbey fans are so passionate, there has been pushback to the book. The writer Doug Peacock, a friend of Abbey’s and the model for Hayduke in The Monkey Wrench Gang, says that Abbey was wrongly mislabeled as misanthropic, and he doesn’t think it’s fair to paint him in today’s light. ”One should be careful writing intimately about a defenseless dead writer, implying (in the version I read) he was a less than exemplary father when his widow and children are standing by,” he wrote in an email, saying he didn’t like the book.

Moab’s Back of Beyond bookstore, which started as a legacy to Abbey and also helped publish Desert Cabal, canceled its planned 50th anniversary celebration of Solitaire due to conflicts over the book. Andy Nettell, owner of Back of Beyond, says that Peacock’s reaction is part of why he thinks Desert Cabal is important—it reflects a changing environmental ethic and the rise of the #MeToo movement and broadens the scope of stories. He thought it was crucial to have a woman’s voice in the conversation. “Amy’s run into a couple of old-school white males who have taken her to task. I sense that there was this very protective feeling, of protecting Ed, protecting Ed’s legacy,” Nettell says. “The feedback initially upset me, but then it energized me, because it’s underscoring the whole point. It’s hard to go back to it, but it’s caused a lot of people to reexamine Desert Solitaire.” Nettell didn’t want to shy away from controversy, in part because Abbey wouldn’t have. He says he often hears from young women and people of color who come into the shop that Solitaire falls flat for them because they can’t see themselves in it, so he was glad to give them more options. Abbey is still front and center—metaphorically and literally—when you walk into the shop, but he’s not alone on the shelf.

It’s hard to reread and dissect the things you’ve always held true, but it is 2018, and most of us are deep in the shitty reality of recognizing that our idols are fallible humans. Now we’re in the slow, picky process of starting to tell our own stories, not just sitting with the literary canon. That’s the balance of love and anger. You can appreciate Abbey without needing to follow him.

A cabal is a gang, so Irvine’s title is also her thesis: We need more voices. “If we want to save the wild remains of the nation, we’ll need a broader, more cooperative constituency that includes women, indigenous people, and other underrepresented others,” she writes. “And we’ll have to tread more lightly.” Treading lightly comes from thinking about hard ideas. My biggest complaint about the book is that I wish she’d pushed it one step further. I wish she’d written her own narrative instead of responding to Abbey. I want to hear stories that aren’t his.

Three Other New Books We’re Excited About

‘Congratulations, Who Are You Again?’ by Harrison Scott Key

���ϳԹ��� contributor Harrison Scott Key’s memoir about what it means to be a writer—and why anyone would put themselves through the torture—is poignant and funny. Read it if you liked his ���ϳԹ��� essay “My Dad Tried to Kill Me with an Alligator.”

‘Nine Perfect Strangers’ by Liane Moriarty

If you’re skeptical of the whole cult of wellness, this novel from the author of Big Little Lies will give you plenty of fodder for snark. Read it if you liked Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s feature “We Have Found the Cure! (Sort Of).”

‘The Curse of Oak Island: The Story of the World’s Longest Treasure Hunt’ by Randall Sullivan

For more than 200 years, treasure hunters have been trying to find supposed buried treasure on an island off Nova Scotia. Sullivan tags along on a recent quest and digs into the history. Read it if you liked Peter Frick-Wright’s feature “On the Hunt for America’s Last Great Treasure.”