Long-term drought doesn’t engender snappy headlines, but it’s one of the most damaging, stressful, and dangerous weather disasters we deal with. You can escape rising water and prepare for hurricane-force winds, but there’s little you can do when the skies clear out and the ground dries up. The old saying that “drought begets drought” isn’t just a saying—there is truth to the idea that a severe drought can sustain itself for long, long time.

A drought occurs when an area goes without its normal amount of precipitation for an extended period of time. A drought can have short-term effects—turning your lawn brown—or long-term effects, like decimating a region’s crop yield and running reservoirs dry. The severity of a drought depends on the affected area. It’s easier to break a drought and recover from its effects in the eastern United States than it is in the western United States. But in the West, it’s . The water from heavy rain doesn’t last forever, and a hot summer can parch the ground fast in, for example, the parts of southeastern Texas that were swamped by Hurricane Harvey’s historic rains. This area returned to a moderate drought just 11 months later.

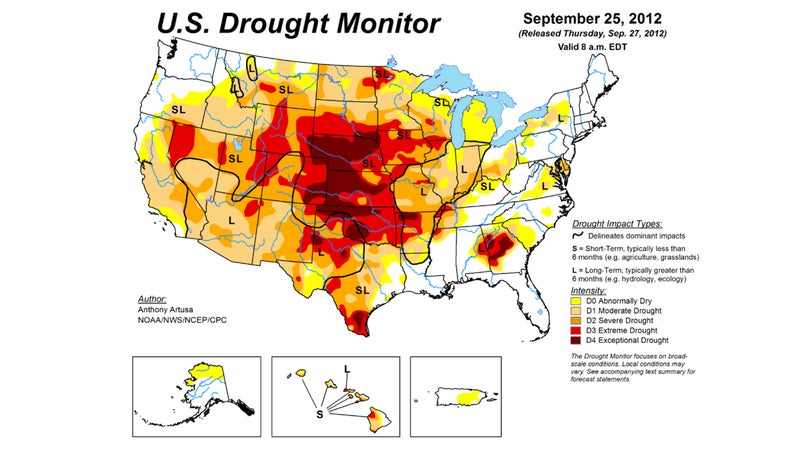

We’ve seen our share of devastating droughts across the United States in recent years. The found that more than 60 percent of the country fell under some level of drought conditions by the end of September 2012. Over the past ten years, exceptional droughts in the Southeast, southern Plains, and West Coast have cost farmers billions of dollars, brought local water supplies to the brink of failure, and allowed wildfires to spark and burn millions of acres.

It takes a broken weather pattern to lead an area into exceptional drought. The recent years-long drought in the western United States was in large part driven by abnormally warm waters in the northeastern Pacific Ocean. The warm water allowed a near-permanent ridge of high pressure to build across western North America, keeping this part of the world warm and dry for months.

But it’s not just the large-scale patterns driving drought conditions. One of the dirtiest tricks of a drought is that the drought-stricken land can actually help keep the weather warm and dry, leading to a situation where the drought prolongs itself.

In the United States, we get most of our rain from pop-up showers and thunderstorms, like the ones we’d see on a hot summer day. Thunderstorms that form in the humid air of a hot afternoon can drop a quick inch of rain, no problem. One of the requirements for those daily pop-up storms is humidity—not something you get much of in a drought. Stubborn ridges of high pressure in the atmosphere foster warm and dry conditions across areas stuck beneath them. These daytime thunderstorms also rely on humidity provided by the land—sources like croplands and bodies of water. One of the major reasons it’s so humid in the central United States is that crops give off tons of moisture into the atmosphere. When the crops are dead and the ground is so dry it starts to crack, there’s that much less moisture to feed thunderstorm development.

This drought-driven lack of humidity also allows air temperatures to grow hotter than they would under normal conditions. Moist air warms up and cools down more slowly due to the high heat capacity of water. This is why it still feels miserable on a July night in Miami, but it can hit 100 degrees in Las Vegas during the day and get so cool at night that you need a jacket. The hotter air in drought-stricken areas can dry out the land and local water sources even more quickly, speeding up the feedback cycle that makes a drought even worse.

If drought begets drought, then how does a drought end? It usually takes a major shift in weather patterns to get the rain going again. Seasonal shifts can do the trick—the jet stream moving south for the winter can help kick-start a rainier pattern in some cases. We’ve also seen droughts broken by landfalling tropical cyclones. As we’ve seen in extreme examples over the past few years, a storm’s legacy begins only when it hits the coast with intense winds. Storms can bring many inches of drought-busting rains hundreds of miles inland, helpfully ending drought across areas in the path of the storm.