Andy Walshe, the former head of human performance at , knows many adventure athletes who have rituals. “As much as they do a physical warm-up, they also do a psychological warm-up,” says Walshe, who now consults for professional sports teams and is working with the computer and gaming accessories company on a program to better understand how humans perform. We asked for his insight on the following athlete rituals. What are they doing right and wrong?

Shaun White

Snowboarder

“The night before a competition, I always eat a steak dinner. The one time I didn’t was when I lost the Olympics in Sochi. When I have three guys in front of me in competition, I do this: The first guy to drop, I put my left binding in. The second guy to drop, I put the right binding in. The third guy to drop, I push myself out into the gate area and watch him ride. I don’t watch any of the runs in full except the one just before me. I do this sequence because it happened once at a competition and I won. If the guy before me falls, I’m going to go nuts and give the judges a show. If he makes his run, I have even more motivation to nail mine.”

Andy Walshe: “A pre-event routine is something an athlete can exercise a sense of control over. The structure of White’s is so rehearsed that it likely allows his brain to focus on his more tactical approach to the event. As for the steak dinner, it can be risky to have a dependency on a certain food. If you have to eat a particular food and it isn’t available, what will you do then?”

Bear Grylls

Survival Expert

“I cross myself before every skydive. My grandfather used to do it before taking off in a plane, and I always liked it.”

Walshe: “Turn on any television and you’ll see athletes crossing themselves, praying, kissing crosses around their necks. You see religion everywhere in sports. Spiritual routines like Grylls’s are very personal. A moment of reflection can clear away distractions and be very grounding.”

Daron Rahlves

Ski Racer

“My ritual started with my first win on the World Cup. Black clothes meant it was on. Black socks, black base layer. Then right before the start, I’d do an eight-second sprint to get the heart pounding and then mental imagery locking in the smooth and fast feeling. Last words: Crush it!”

Walshe: “I’ve seen it all—athletes with lucky socks, precise ways of putting on shoes. When someone has identified a lucky charm—in Daron’s case, a color of clothing—there’s some research that says people who connect to a physical thing experience a small per-formance benefit from that placebo effect. Some of these events, like ski racing, are won by very small margins, so that can make a difference.”

Diana Nyad

Swimmer

“I was compulsive, to an OCD degree, with my gear bag before a big swim. I would pack, unpack, pack all the individualized pairs of goggles, caps, extra suits, chafing gels. Each item had to rest in a particular space in the bag, to the point that I could reach in with my eyes closed and pull out the nighttime goggles in one deft move. I would do 100 arm windmills, then touch down to ground left, then right, with breath mantras for each move: 25 count English, 25 German, 25 Spanish, 25 French. Each one perfectly executed, each breath in sync. Then I’d put my robe on over my suit, goggles always in left pocket, cap in right.”

Walshe: “There’s no downside to an athlete’s routine—unless they become dependent on it. Say you have a rigorous one-hour routine, and for some reason, you’re not able to do it. Then you’re putting yourself at risk of having that impact your performance. Like Nyad, many top athletes slow their breath before big events. The simplest way is this: breathe four seconds in, four seconds out, for four minutes. It can lower your heart rate.”

Mikaela Shiffrin

Ski Racer

“I make a playlist of 15 songs that I listen to on repeat. Each song gets me focused or pumped up. I also make a more meditative playlist with piano or classical music to keep me calm. In between runs, I’m surrounded by noise. In order to stay calm and focused, my noise-canceling headphones have become a hugely important tool in my routine.”

Walshe: “Go to any high performance locker room and music is being used. It’s an ancient tool—the drumbeats marching into battle. Music can signal to your brain that it’s time to focus. In individual sports, like Shiffrin’s, it gives the athlete a chance have their own space in a busy environment.”

Herbert Nitsch

Freediver

“Between my last warm-up dive and the final dive, I zone out totally until I have a bird’s eye view of the whole event below me. I observe the diving platform, judges, spectators, cameramen, and myself from above. I remain in this mode up until my last breath, after which I dive back into the confines of my skin, and venture below the surface. It calms me down tremendously, which is important in this sport where adrenaline is my foe.”

Walshe: “There are a lot of arguments in terms of the efficacy of visualization. When you do it, the visual cortex activates and lights up the same way as when you actually see something. It’s like the brain version of virtual reality—you get to experience a place without actually being there. But don’t get bogged down by the details, in case the experience doesn’t turn out how you visualized it.”

Alex Honnold

Climber

“My routine is about limiting the number of decisions I have to make and avoiding variables. So I’ll pack my bag the night before and make my breakfast, which is generally the same muesli and fruit when I’m in my van. I’ll do whatever I can to prepare ahead of time. I’ll often wear the same clothes, but again that’s more about knowing exactly how they’ll perform and avoiding surprises. I want to execute a big climb exactly the same way that I’ve prepared for it.”

Walshe: “Getting everything squared away up front is a huge advantage. For Honnold, a checklist could give him a precise way to make sure everything he can control is taken care of. People in high-risk pursuits—parachute jumpers, deep-sea divers, big-wave surfers, or military operators—they all typically have very strong routines. It’s a significant part of what makes them feel safe.”

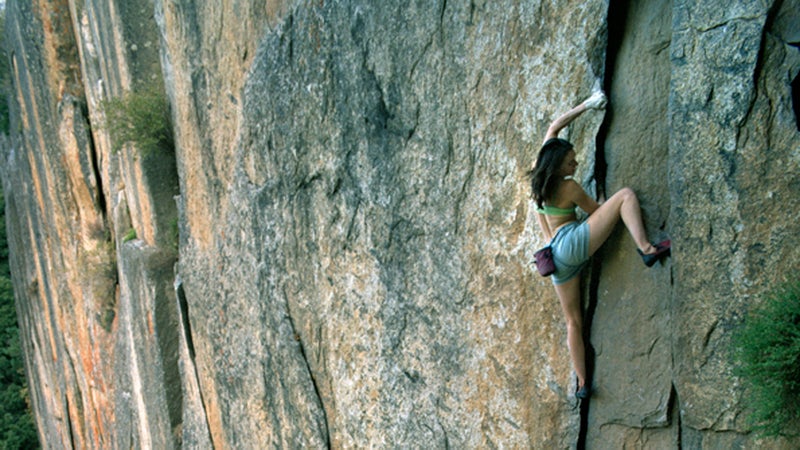

Steph Davis

BASE Jumper and Climber

“There are a lot of intense emotions when you’re about to jump off the edge of a cliff . When I know I’m just about ready to go, I shake my shoulders, take a deep breath, and smile. It makes me feel positive and confident, which is what I need to perform through the first few crucial seconds of a wingsuit jump.”

Walshe: “Davis’s smile is important. Humor is an unsung hero in intense moments. You see the tension rising, then a smile or laugh can bring someone back to earth and relax them.