Like a lot of people who’ve reached middle age, when I picture myself, I still see an invincible 20-year-old kid, ready to charge up mountains. Fortunately, I’m aware enough to know that, at 44, I’m better off relying on my wisdom than my muscle, whether at work or at play. I’m more cautious these days, but also more precise. My experiences have served me well and I’ve evolved.

I wish I could say the same of the Endangered Species Act.

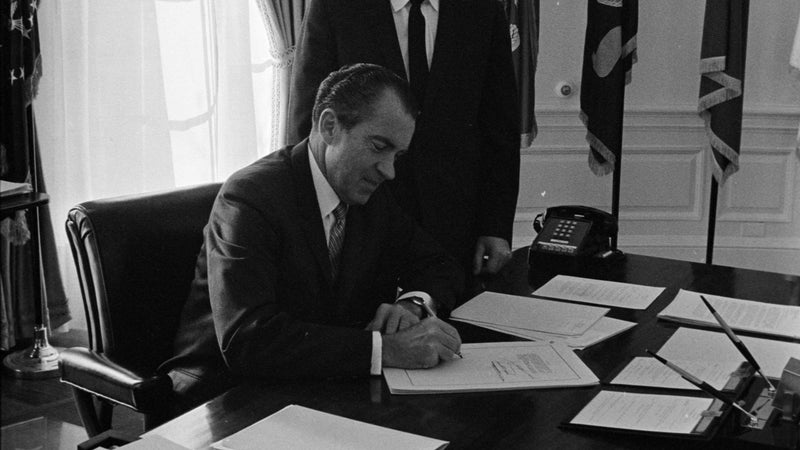

Like me, the act was born in 1973. Passed at the height of the postwar environmental movement with overwhelming bipartisan support and signed by President Richard Nixon, it was a law as well as an ethical statement: No animal or plant species should ever be permitted to go extinct. In the years since, we have learned a great deal about the complicated mechanics of protecting species, yet Congress has not significantly amended the act since the 1980s.

The Endangered Species Act has two main objectives: prevent the extinction of plants and animals, and restore endangered species to the point where they no longer need protection. States have authority over most of the wildlife within their borders, but when a species becomes endangered, the act empowers the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service to take action. Under the law, these agencies can ban hunting or harvesting, restrict land uses within a species’ range, and designate critical habitat, among other measures.

Since the act’s passage, only 11 protected species out of more than 1,600 have gone extinct. This is a huge conservation victory. Yet, over the past 43 years, just 51 species (or around 3 percent) have recovered to the point where they could be removed from the endangered list. Twenty-eight of these recoveries occurred during the Obama years, suggesting that things have been heading in the right direction.

Politically, these numbers are like a Rorschach test. The act’s supporters claim that when given enough funding, enforcement, and time, the law works. It has, after all, done a wonderful job of preventing extinctions. However, opponents of the law point to the small number of recovered species as evidence that the act is failing.

The result is a stalemate. Conservationists and their Democratic allies in Congress have shown little interest in amending what’s considered to be the world’s most powerful species-protection law. In the past quarter-century, Democratic lawmakers have rarely proposed significant updates to the act. Meanwhile, over that same time period, conservative detractors have proposed dozens of bills that would gut the act’s key provisions. As of this spring, five GOP-authored bills to amend the act were circulating in Congress. One would pressure the government to consider economic impacts before protecting a species. Another would force federal agencies to incorporate data from state, tribal, or county governments, even if it’s biased or inaccurate. None of these bills offer the kind of thoughtful modernization the act desperately needs.

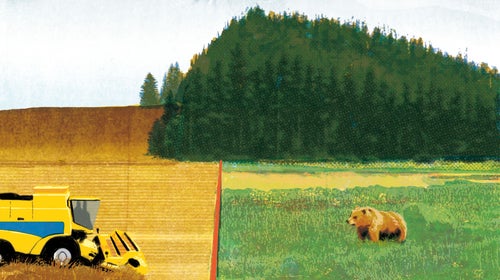

What gets lost in the partisan bickering is the fact that there’s actually broad public support for the goals of the act. A number of opinion polls have shown this, though many were commissioned by environmental nonprofits. What people usually object to is the idea of the government telling them what they can and can’t do on their land. When an animal or plant is declared endangered, the federal government has the authority to halt development projects in the species’ habitat. But the truth is that this very rarely happens. Additionally, the enormous amount of attention given to cases like the northern spotted owl, whose listing led to a fierce battle between logging companies and environmentalists in the Pacific Northwest in the 1980s and ’90s, has spurred the false perception that the act is a giant job killer. In reality, the job losses in industries like logging and mining that have devastated many rural communities are due to macroeconomic forces like depleted resources, globalization, and technological advances.

The Endangered Species Act can do better. Three fundamental changes in how it functions would do a lot to move us past the political gridlock while powering the recovery of many more species.

First, let’s upend the economics of an endangered listing by borrowing a page from the farm bill. A program called allows the government to pay farmers to manage their lands in ways that support certain animals. Find an endangered bobwhite in your field, for example, and instead of giving up on your crops, you can earn money by being an environmental steward. This model has proven quite compelling, helping conserve more than 7 million acres of habitat, which is why some states have their own versions. California’s , for example, provides property tax relief to farmers who agree to preserve open spaces.

Second, the act needs strengthened provisions that entice stakeholders to create effective and legally binding management plans for threatened plants and animals before they are listed as endangered. As it stands, the act allows for the development of local proposals but doesn’t offer guidelines as to what constitutes an acceptable plan, nor does it grant adequate legal weight to these agreements. This leads to a lot of poorly designed plans—as well as smart ones that may be tossed aside after an election.

What gets lost in the partisan bickering is the fact that there’s actually broad public support for the goals of the act.

Take the case of the greater sage grouse, that puffy-breasted bird of the West. When it became a candidate for the endangered species list in 2010, the fear of federal intervention compelled ranchers, developers, and states to devise their own protection plan. Five years later, they agreed on 98 specific habitat-management plans across ten states. It wasn’t perfect, but it was a workable compromise. Then Donald Trump won the presidency, and the Interior Department promptly put the plan under review—the first step in destroying it.

Lastly, when negotiations over a specific piece of land or project reach an impasse, the act needs to provide a way forward that fosters species recovery. Currently, the act demands only mitigation. Individuals and groups can apply for an incidental-take permit, which stipulates that a project can harm an endangered species in one place if efforts are made to aid the species somewhere else. But neutralizing overall harm doesn’t move a species any closer to recovery, which is why environmentalists frequently oppose these permits. We need an amendment that requires projects to actually improve a species’ status, not keep it the same.

Conservation faces major challenges in the decades to come. Setting aside vast reserves of land has become far more difficult than it once was. Hunting and fishing, which have typically funded conservation though permit fees, are in decline. Then there’s the 800-pound gorilla of climate change. The Endangered Species Act, however, is something we can control. It’s a rare cause that most Americans support—and would probably support more fervently if it were modernized. Instead of reflexively defending or attacking the law, it’s time we improve it.

Where would any of us be if we had not learned from our experiences?

Peter S. Alagona is the author of . He is an associate professor of history, geography, and environmental studies at the University of California at Santa Barbara.