Raise your hand if you can relate to this scenario: You pull a fresh pint of Ben and Jerry’s from the freezer, intending to enjoy a couple of bites. Twenty minutes later, you’re lolling on the couch, empty carton on the floor, second-guessing your life choices and vowing to start that new fitness regimen first thing in the morning.

If only you had more willpower, right? It turns out, you shouldn’t be so hard on yourself: you’re up against a couple hundred thousand years of human evolution, combined with a food industry bent on exploiting your most powerful instincts. Two recent books further illuminate the role our brain plays in the often uncontrollable urge to overeat.

“Of the 2.6 million years since our genus Homo emerged, we were hunter gatherers for 99.5 percent of it, subsistence farmers for 0.5 percent of it, and industrialized for less than 0.008 percent of it,” writes Stephan Guyenet in . “Our current food system is less than a century old, not nearly enough time for humans to genetically adapt to the radical changes that have occurred…. Many researchers believe this evolutionary mismatch is why we suffer from such high rates of lifestyle-related disorders.”

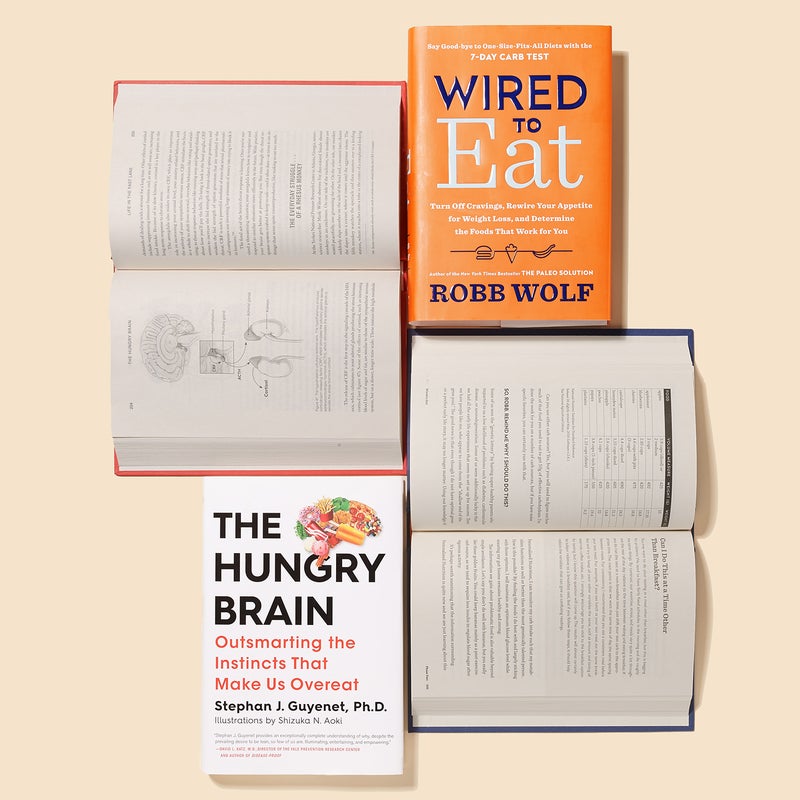

Guyenet is an obesity researcher and neurobiologist and founder of the popular wellness and science blog . In The Hungry Brain, he largely ditches the macronutrient debate—carbs versus protein versus fat—and takes us upstream, to the role our brains play in appetite and eating. Essentially, he explains, there are two systems in action in the brain: one that exists in places like the prefrontal cortex (PFC), where our conscious, rational, and enlightened thinking takes place (e.g., eat more broccoli, less breakfast cereal), and one that operates from areas including the basal ganglia, where our calorie-craving instincts reside.

We are driven to consume sugar, salt, and fat because that’s where the most calories reside. Thousands of years ago, it kept us alive. Now it just makes us fat.

Scientists have come to understand the instinctual part of our brain in part by studying lampreys. Looking at lamprey brains has helped illuminate the fundamental circuitry involved in less conscious decision-making. What we now know, thanks to recent neuroscience research, is that some 560 million years after the common ancestors of humans and lampreys diverged, our highly evolved brains are still heavily influenced by the same core operating system. We are driven to consume sugar, salt, and fat because that’s where the most calories re-side. The Ben and Jerry’s binge? That’s your lamprey brain kicking some PFC ass. Thousands of years ago, it kept us alive. Now it just makes us fat.

The dichotomy raises the unique challenge of figuring out how to manage our diet in an environment that has shifted, relatively abruptly, from scarcity to abundance. Guyenet argues (unfashionably) that federal nutrition guidelines, which first appeared in 1980, have delivered sensible advice: eat less, move more, limit sweets, throttle back on booze. We’ve just struggled to adhere, which should surprise no one.

Since the guidelines were released, the number of items in an average grocery store have increased dramatically, from around 15,000 to nearly 40,000, according to the . Many of those products now come out of sophisticated food labs, having attained the now infamous “bliss point”—a flavor combination that promotes maximum craving. “Nonconscious parts of the brain perceive certain foods as so valuable that they drive us to seek and eat them, even if we aren’t hungry, and even in the face of a sincere desire to eat a healthy diet and stay lean,” Guyenet writes in a chapter titled “The Chemistry of Seduction.” Even worse, we are also wired to conserve energy—that is, be lazy—creating a metabolic double jeopardy.

So what are we to do about all this irresistible food that has such a grip on our helpless brains? Robb Wolf, the biochemist and food researcher often credited for helping launch the paleo phenomenon and the author of , offers a solution.

Wolf is bullish on diet, but he reminds us that stress, movement, and sleep are also key factors that impact how the brain regulates appetite and metabolism. “Good sleep,” he writes, “buys us a lot of latitude in our eating.” And conversely, if you’re not sleeping well, “you really need to pay attention to your food, particularly carbohydrate amount and type.”

In Wired to Eat, Wolf proposes a “30-day reset,” a diet and lifestyle makeover that he lays out in considerable detail, with step-by-step instructions that he compares to an Arthur Murray dance program. Most of the plan is a paleo-ish diet, along with tips on sleeping better, moving more, and reducing stress. After the reset, Wolf advises a seven-day carbohydrate test, which uses a glucometer to examine your body’s insulin response, primarily to various types of carbohydrates. The end result is a personalized plan, with a surprising amount of latitude, that gradually rewires your brain toward improved health and performance.

Like Guyenet, Wolf subscribes to the idea that we are grappling with an evolution-environment mismatch. We’ve made big strides in understanding how this impacts our bodies, but the real key to controlling and reversing those impacts may reside in our head. As Guyenet puts it: “The brain generates all behaviors—what and how much you choose to eat, how you use your body—and it regulates a lot of your physiology as well. It’s very much the obvious place to look.”

Nix Your Fix

The key to rewiring your brain is making adjustments to your environment. Guyenet offers six steps to help kick-start the process.

-

Don’t want to eat it? Keep it out of the house. Empty your cabinets, fridge, and freezer of junk foods that tend to spark binge eating.

-

“Choose foods that send strong satiety signals to the brain stem,” writes Guyenet. This includes foods higher in protein and fiber, like meat, fish, avocados, veggies, potatoes, and whole grains.

-

To eliminate cravings and overeating, try to avoid foods that present highly palatable combinations of salt, sugar, and fat.

-

Get enough quality rest to help control appetite in healthier ways. Keep your bedroom as dark as possible, set it to a cool temperature, and minimize screen time before you turn in.

-

You don’t have to crush yourself at the gym, but you do need regular movement—this means walking, riding a bike, doing yard work, or taking the stairs.

-

Stress less. It often prompts mindless, unhealthy eating. Identify specific stressors, write them down, and outline ways to control them better. Also, make meditation a part of your day.

Listen to our conversation with Stephan Guyenet on the ���ϳԹ��� Podcast.

Listen to our podcast interview with Stephan Guyenet

Listen to our podcast interview with Stephan Guyenet