Where in the Hell Is Our Cat?

A wintertime search-and-rescue drama that began with a predawn disappearance and a single terrifying clue: blood. No big deal, though. All we needed was a miracle.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

“There was a lot of fur,” said a woman named Diane.

Yeah, there was. I was standing with my wife, Susan, on the back patio at Diane’s house, looking at a dozen little off-white tufts that were getting nudged around by a breeze. Kneeling amid old snow and empty cat-food bowls, I collected a sample that went into a tiny plastic bag, like I was working a crime scene. Ridiculous? Sure, but it felt right. A cat had been in a rumble out here, and we were trying to figure out if it might be ours.

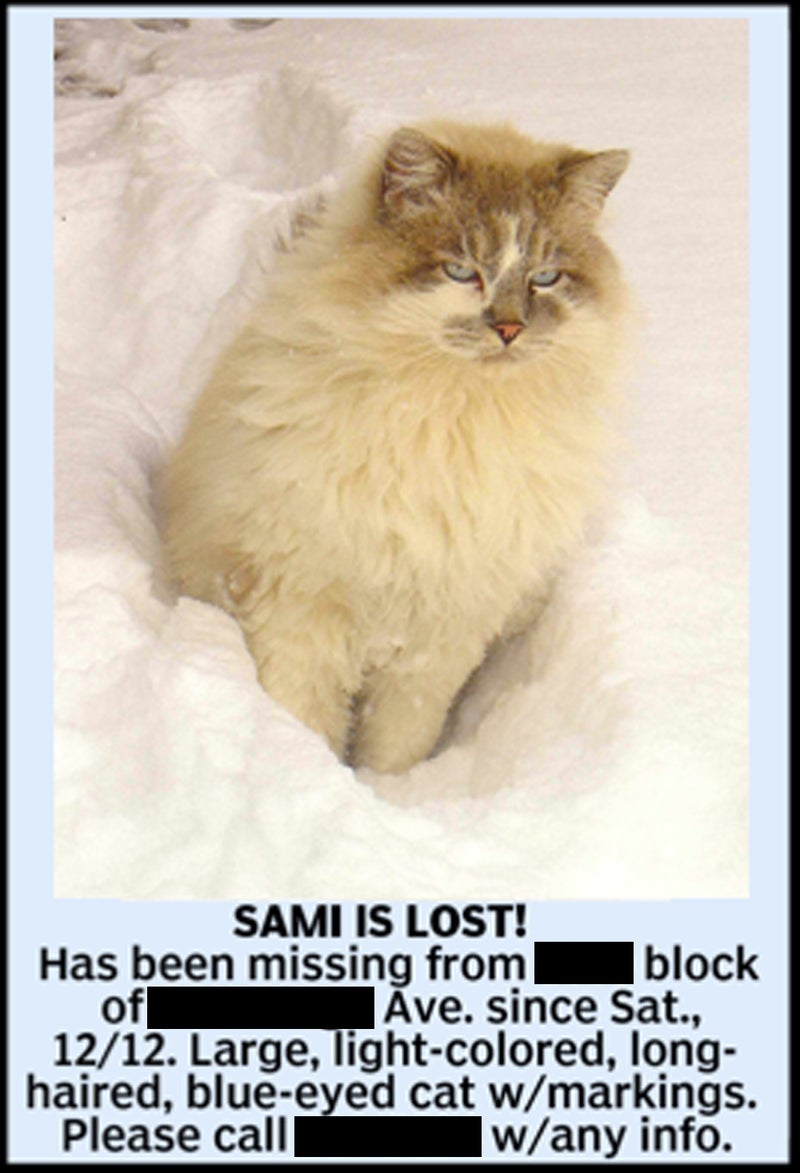

Diane was a kind person who had called to report the latest lead in the agonizing search for Sami (pronounced “Sammy”), a handsome, friendly, long-haired male that we adopted in early 2012. He showed up one morning at our house in Santa Fe, looking hungry, lonely, and in need of immediate TLC.

Several excellent years followed, during which time Sami blimped up to 13.5 pounds, enjoyed life, and escaped harm—not counting the little things, like him getting chomped on the face by an enemy and having to wear a cone for two weeks. He disappeared just before sunrise on the morning of December 12, 2015, when Susan let him out after he’d slept most of the night on a living room chair. Usually he would nose around for a while and then sit near the front door, waiting to be let back in and fed. But on that day, he didn’t return.

It was now a month later. It snowed hard the day Sami vanished, plus a couple more times after that; most nights, the temperature plunged into the low teens. Various attempts to find him—a barrage of classified ads, posters, flyers, and boots-on-the-ground searches—hadn’t worked, and I had trouble imagining how Sami could survive that long in such frigid conditions.

I also had a sick feeling he didn’t make it off our property alive, because of something I saw that first morning: a big drop of blood next to his outdoor kibble bowl. The blood had been partially smeared onto a slab of flagstone by…I didn’t know what. About 15 feet from that spot, an iron gate leads from an enclosed garden to our small front yard. The gate had been shoved open by…I wasn’t sure, but I thought I could visualize how it all might have gone down: A passing coyote saw Sami, pushed the gate open, and chomped him before he could get away. After that, I assumed, he was carried off and devoured.

This image was not far-fetched. Our house sits roughly two miles west of the Rocky Mountain foothills, close enough to real backcountry that dangerous creatures show up now and then. One day a few years ago, I came home and saw Sami trotting down the middle of the street, about 20 feet behind a coyote that he probably thought was a potential new friend. (I grabbed him and ran the other way.) Once there was a roaming the area, just a few blocks from us. Three years ago, somebody who didn’t want their anymore turned it loose on a sidewalk. Dogs come galoomphing onto our lot pretty often, and there’s always the possibility of or death from above: .

Sami’s disappearance cast a black cloud over Heardville. Every day, I slogged around in despair, and Susan was waking up in the middle of the night, crying. I scrubbed away the bloodstain and decided not to tell her about it yet—a white lie that put me in a bind. Though I felt certain Sami had died, I had to proceed as if he might turn up at any moment.

To that end, I resolved to investigate every lead, no matter how lame. One night in late December, after Susan had placed an ad in two local newspapers—with a sad but on-point headline that read “SAMI IS LOST!”—a woman called and said she’d seen a cat who looked like Sami padding around inside an empty house that was for sale in her neighborhood.

Hmmm. Had our guy figured out how to enter locked buildings? We drove over there—it was two miles away—and I parked, walked up the driveway, and pressed my face against a wide picture window that offered a view of the living room. Sure enough, a chubby cat was sitting on top of a couch with its back to me, watching TV. But it wasn’t Sami, and the house wasn’t empty, as I discovered when I rapped the window to get the cat’s attention. A woman who was lying on the couch below him stuck her head up, startled. Sorry!

Diane’s sighting seemed more plausible. Her house was only five blocks northeast of ours, and though she hadn’t seen Sami, the tufts she found proved that a cat with his coat type had been here. As Diane described the moment, she was sitting inside one night when she heard yowly cat-fight noises in her backyard. She went outside; the cats were gone, but she found several thick, white puffs. Diane had seen Sami’s poster and decided there might be a match.

Every day, I slogged around in despair, and Susan was waking up in the middle of the night, crying. I scrubbed away the bloodstain and decided not to tell her about it yet—a white lie that put me in a bind.

Peering at the fur samples later, alongside fur from Sami’s brush—and yes, we did use a magnifying glass—we couldn’t really tell. I’ve said Sami was off-white, but viewed up close he had a lot of colors going on: pure white, cream, beige, brown, taupe, slate, and apricot. His pelt might have matched any number of random samples.

One thing was certain, though: Diane’s home could have attracted his attention. Her place has a detached, doorless garage, and she’d set up a heating pad inside, similar to a wintertime crib Sami enjoyed in our house’s garage, where he shared space with his two best friends from the neighborhood: Monkey and Twinkletoes. Maybe he’d come here and tried to edge his way into the warmth and comfort this refuge offered, only to be driven into the night by home-turf jerks?

I looked at the garage: A pair of surly shorthairs sat blinking near the entrance. I glared at them but then turned away. It wasn’t their fault if they were territorial—most cats are, including Sami, who sometimes ran off anybody who wasn’t part of his three-cat posse. That’s just part of The Life.

Running a search and rescue operation for a cat is a whole different deal than looking for a lost human in the wild. With a person, the seekers usually have a general idea of where they might have gone, even if the terrain involved is enormous. Once that’s known, ground and air teams can start beating the bushes. If they get close, the rescuee has the ability to communicate with shouts, flapping arms, a whistle, etc.

With cats, you are the ground and air teams. You have no idea which way the animal went or how far, and the cat can’t tell you where it is except by bawling or showing itself if you happen to walk by. But even then, the shuddering waif might hide because it’s terrified. Websites that specialize in Lost Cat Theory, like explain that a typical outdoor cat that’s missing is often only a few blocks away, hunkered down and mind-scrambled after getting chased off by something scary.

But I knew from experience that they can roam farther than a few blocks. Back in 1992, when Susan and I were living in Chicago, the first cat we owned together—a black male shorthair named Commander—freaked out and ran off soon after we moved there from Washington, D.C. (What upset him so much? Our belief was that he saw a TV ad featuring either or deep-dish pizza.) Luckily, he was wearing a tag with our phone number on it. He was found two weeks later, four miles west of where we lived, begging for food in an elderly woman’s backyard. She told Susan that she would have called sooner, but she thought the phone number was (um) “his Social Security information.”

Sami was alone and naked out there—no phone number, no home address, no federal tax ID, no college transcripts, no collar, no nothing except for a microchip under his skin, which doesn’t do any good unless an animal winds up at the pound and gets scanned. For a while, during his first months with us, he wore a leather collar with all his info on a tag, but a rig like that can be dangerous. One morning he came home after two nights of being AWOL, and the collar looked twisted in a way that made me think he’d gotten hung up on a fence. We tried a safety collar with a breakaway latch, but he laughed and kicked that off within hours.

Which brings us to an FAQ: Why did we let Sami go out in the first place, since that’s unsafe for him and potentially bad for songbirds, mice, and moles? Valid points, but there were unique aspects to his situation, dictating that he have the freedom to roam.

For starters, Sami came to us feral and never lost all his wildness, so he resisted being fully tamed. The great arrival happened on a cold February morning, when Susan looked out our bedroom window and saw a big, billowing cat sitting on a flat-roof corner of the house next door, staring into a frigid west wind like one of the soldiers in . This animal was so striking—intense blue eyes and a mysteriously expressive face—that neither of us could quite believe it.

Before long, Sami wobbled to our front door and made it clear he wanted to stick around, so we started feeding him and got him fixed. Since it was midwinter, I left the garage door open and made a box-and-blanket crib that he could sleep in during brutal nights. Over time, I added a cozy pair of barn-cat heating pads and a radiator, and Sami had a real home. His coat was colored like a reindeer’s, so Susan named him after the of northern Scandinavia, who I met once for an şÚÁĎłÔąĎÍř story.

In wintertime, we often let Sami come in for a few hours after dark to snooze near the TV while I sat with him. We thought about trying to convert him to full-time indoor status, but we already had two rescued cats inside, a brother-and-sister team whose fat-tail grumblings made it clear they weren’t open to a newb. In addition, Sami never understood what a litter box is for, and (trust me) I tried to teach him by every means short of a live-action demo. Four times—after various injuries or medical procedures—I had to shut him in the garage for more than a week. Sami never used the litter box I put in there and was miserable about being locked up.

My colleagues at şÚÁĎłÔąĎÍř are dog people, overwhelmingly, and the magazine and website regularly publish canine worship that verges on porn. “Hunting dogs are smart, powerful, and beautiful,” blared a typical şÚÁĎłÔąĎÍř tweet linking to a photo gallery of pointers and retrievers. “And they’re dogs, so we love them extra.”

I love dogs, too, but in terms of pure cuddliness and entertainment value, Sami took a back seat to nobody. During warm-weather months, I’m in the yard a lot, watering plants and pulling weeds. Sami was usually with me, and his presence was an immeasurable contribution to the fun spirit of our home. (Half seriously, Susan said that if we never found him, we’d have to torch the place and leave.) He liked to run around, get chased, snooze, climb trees, get fed, get brushed, and be comforted with behind-the-ear scratches. Despite my pessimism, there was no way I’d let Sami die alone—wondering why his friend hadn’t come to help—without giving the search maximum effort.

As things had developed, the Diane lead from January was not our main focus. Susan’s newspaper ad debuted in mid-December, and I assumed my phone would never ring. But it did, starting about a week before Christmas. An excited man said he’d spotted Sami at a shopping mall, roughly a mile and a half north of our house. He’d seen him two days earlier, lurking by the mouth of a large drainpipe at the edge of a parking lot. “He was big and white, and he was really an amazing-looking cat!” the man said.

Positive ID! Or maybe not. I went to the mall and couldn’t find the pipe. The spot I think the man meant had been covered by a huge push from a snowplow, which gave me something new to worry about: What if Sami was in there, trapped and starving?

With the physical realm pretty well covered, we sought additional help from the spirit world—which is easy to do in Santa Fe, where you can’t throw a Wiffle ball without hitting a psychic.

The idea that he’d traveled all this way seemed crazy when I looked at a map. Between our house and the mall, Sami would have had to cross four major streets, a bunch of minor ones, and the deep ditch of the Santa Fe River. This with snow on the ground and Sami, a big pig, subsisting on whatever calories he could hunt or scrounge.

And yet…I kept getting calls, and they started to sound convincing. About a week later, a woman named Carol phoned from an apartment complex half a mile northwest of the mall. She’d seen a cat she thought was Sami two days earlier, cavorting on a big lawn where the snow had melted. I drove over, and we walked to a communal laundry room, where I pinned up a Sami flyer. Carol peered closely at his picture. “That sure looks like him,” she said.

I felt a chill and started to buy in, especially after I walked the grounds and saw how cat-friendly the place was. There was a heated fountain on the lawn, perpetually bubbling; signs of burrowing rodents; and rabbits, songbirds, and a roadrunner moving around sleepily on snowless patches of winter turf. Almost every apartment had a small patio space out front, often filled with couches and chairs—perfect shelter for a needy feline. Maybe Sami had covered two miles while blundering around lost, arrived here, and recognized it as an ideal place to make a stand.

I found the apartment manager and asked if I could set out a few humane animal traps loaded with stinky fish. Her astonishing answer: no. So I spent the rest of that freezing day hiking around the building and the neighborhood, papering stairwells and telephone poles. Susan did similar yeoman’s work in our neighborhood, and she knocked on many doors to ask if anybody had seen Mr. Wonderful. The door-to-door thing was a pain but unavoidable: The vast majority of backyards in Santa Fe are enclosed by high walls, so you can’t just stroll around in alleys hoping to see something. If you start hopping fences, you’re trespassing, and you might find yourself in the jaws of a watchdog.

On Christmas Eve, I went back to the apartment complex neighborhood, geared for action. I had a backpack full of flyers, a staple gun, clear packing tape, cat food (dry and wet), canned tuna, a leash and harness, a can opener, a fork, and a bowl. Working weekends and afternoons into the new year, I put up signs in a fan-shaped swath of neighborhood that eventually measured three square miles. Carol, who was out for a walk one afternoon, saw me marching around and shouted across the street: “YOU SURE WANT TO FIND THAT CAT!”

“YES,” I yelled back. “I SURE DO.”

The day after Christmas, a setback: I was flattened by a bad case of flu that lasted two weeks. But my duty could not be shirked. Every time I got a call about a sighting, I groaned, coughed, and staggered out to investigate.

The calls kept coming. In addition to our newspaper ads and flyers, somebody had put up huge bright-green Sami posters, with my phone number on them, near our house and the apartments. (I later learned these were made by Mary Shepherd, a dedicated woman who runs a Facebook page called where I’d posted info about Sami’s disappearance.) About half the calls were from people who didn’t have any info—they were just hoping to hear he’d come home. I tried to break it to them gently.

With the physical realm pretty well covered, we sought additional help from the spirit world—which is easy to do in Santa Fe, where you can’t throw a Wiffle ball without hitting a psychic. Susan has a friend who makes her living as one. At no charge, this generous woman dug deep for a few days, consulted with psychic colleagues who specialize in pets, and emerged with an eerily detailed prognostication: Sami was alive, he wasn’t wounded, and he would eventually return, but it would take a while. Though I don’t usually pay attention to clairvoyants, this time I nodded and evaluated the data scientifically. Twenty-five percent of this prediction was already true, I reasoned, since it was taking a while.

More leads followed. I got a call one blizzarding night from a guy who thought he’d seen Sami run under a parked car at the apartment complex, but by the time I got there, he was gone. A woman called—again, from the apartments—who said Sami had stood on a piece of patio furniture and stared forlornly at her through a window before scampering off. (I found that one especially piercing.) A woman living near the apartments thought she saw him on the grounds of an abandoned office building across the street from her place. She tried to grab him and got clawed on her right hand. Later, when I showed her a few pictures, she didn’t think the cat she saw was him.

This introduced a troubling thought: Could the helpful callers all be wrong? Were they seeing resemblances that weren’t there because they were eager to help?

Possibly, and there were other hints that the sightings might be cruel illusions. One day, a resident of the apartments texted me a picture of a cat he’d noticed, with the message, “Is this Sami?”

Nope: It was a big, white-bodied, dark-faced Siamese, but I could see how somebody might be fooled, especially at night. After that, we heard from a different set of people—in a neighborhood a mile southwest of the apartments—who said they were seeing Sami too. By this point, mid-January, the weather was getting a bit milder and the snow was starting to melt, so it was conceivable that he was covering a lot of ground. But it seemed unlikely. I drifted into a new funk, assuming again that the search was pointless.

About half the calls were from people who didn’t have any info—they were just hoping to hear he’d come home. I tried to break it to them gently.

That’s when a woman named Susanna called, and the trail got hot in a hurry.

Susanna lived with her husband in a south-facing unit at the apartment complex, with a couch on the porch, near the spot where a man had thought he saw Sami run under a car. She called on January 15 and said a cat matching Sami’s description was turning up periodically and sleeping on the couch. One night, she opened the front door to feed it, but it ran off.

I drove over the next day and showed her photos. Susanna seemed fairly sure that the cat she had seen was Sami—the face looked right (Sami’s has patchy markings) and so did the tail (it’s bushy and darker than his body).We agreed on a plan. She would put food out. If the cat showed up again, she would call me—no matter what time it was—and I would zoom over.

Three days later, on the night of January 18, just after 10:00 p.m., my phone rang. It was Susanna: The cat was on the couch. In a few minutes I was speeding over there with a flashlight, food, and a carry bag. My heart was racing as I slapped the steering wheel, feeling psyched. I parked a block away so I could calm down and quietly approach the jackpot zone.

After my initial approach, I got down on all fours and crawled to a spot in front of Susanna’s unit. Then I peeped over a low wooden fence and saw a resting cat that looked like Sami, though it was hard to be sure in the dark. I turned on my flashlight and held it up, pulse thudding in my ears. The light’s glow was weak, so it only helped a little. The cat noticed, stood on the arm of the couch, and stared straight at me.

Or I should say: through me. There was no recognition in its dark eyes, and after a few seconds it jumped down and ran off. The cat looked almost exactly like Sami, but it wasn’t quite him. (The giveaway: not fat enough.) Groan. Now I had to go home and tell Susan that the hopeful signs were a mirage. I hadn’t been that miserable in years.

The next day, around midday, I drove to Susanna’s place to collect some kibble I’d left with her. I went home after that to eat lunch and pout. Pulling into the driveway, I saw a little beige blob weakly kneading wet ground between two dormant rose bushes, about halfway back toward the garage. I knew right away who it was. After putting my forehead on the steering wheel and saying a few words of thanks to my favorite , I called Susan at her job and shouted into the phone: “We’ve got him!” Then I started moving. Sami had been out in the cold for five and a half weeks. There might not be much time to spare.

I don’t know whether Susan’s psychic friend has special powers or just got lucky, but she certainly nailed this one: Sami came back, it took a while, and he wasn’t wounded, as I saw when I picked him up and inspected his pelt while he issued brief, rapid cries of SOS. He was a matted-fur bag of skin and bones, but there wasn’t any sign of injury, and I have no idea where that big drop of blood I’d seen came from. When he was weighed later by a vet, he was down to 7.5 pounds—he’d lost nearly half his body weight—but otherwise seemed fine. That night, Sami and Susan had a long petting-and-purring lovefest, after which, uncharacteristically, he glued himself to my lap for hours.

Sami got a blood test (no problems) and an injection of fluids. At first, he was unable to keep food down, but by day two he started eating like a sled dog. Within a month, he gained all his weight back. A few days after his return, I paid a professional dog groomer to shampoo him. Skinny though he was, he looked faboo.

Susan diligently closed the loop by placing newspaper ads that announced Sami’s return. These prompted about a dozen more calls from well-wishers, who reminded me of how much a happy ending can mean to people. “I lost my own cat—I had to say goodbye to him,” one woman told us in a message. “I lost my brother unexpectedly in October. I just needed some good news. Thank you for letting us know that Sami came home.”

I’ll never know where Sami went, but it’s safe to assume he was closer to us than I thought. (It’s possible he was at Diane’s.) I now think he got chased off by something big and fierce, got disoriented, and then was pinned down by heavy snow. He didn’t feel confident about embarking on his Incredible Multi-Block Journey until the thaw started, so he stayed where he was and somehow didn’t starve to death. Coming home must have been a demanding physical feat: Sami lost so much muscle mass that his thighs felt like plastic bags with chicken bones inside. For the first few days, he couldn’t even jump up onto his low chair by the TV.

Bottom line: Sami saved himself, with an assist from changing weather, instinct, luck, pluck, and, apparently, the Psychic Friends Network. My efforts to rescue him were all misguided failures. I’m more than OK with that.