The first time readers meet Annette McGivney in her crime-investigation-cum-memoir, she is standing at the admittance desk of a psychiatric center. Her condition is bad enough that a doctor agrees to see her. After an examination, he asks her a question to which readers are not privy, and McGivney signals that this question will unearth the reason she’s such a mess. It takes her 23 chapters to circle back to it, but the narrative that precedes her revelation is so rich you’ll hardly notice.

Read the Rest of the Book With Us

We’ll be discussing Pure Land and talking with author Annette McGivney for the ���ϳԹ��� Beyond Books Club.Pure Land: A True Story of Three Lives, Three Cultures, and the Search for Heaven on Earth () is mainly about the 2006 death of Japanese hiker Tomomi Hanamure in Grand Canyon. The 34-year-old was stabbed 29 times in her head and neck near Havasu Falls on the Havasupai Indian Reservation. Her murderer, Randy Redtail Wescogame, was an 18-year-old Havasupai tribal member who dropped out of high school and wrestled with a meth addiction. McGivney on the homicide for Backpacker while working as the magazine’s Southwest editor and as a journalism professor at Northern Arizona University. But, as Pure Land’s introduction intimates, McGivney’s reasons for investigating went deeper than just wanting a scoop. She continued to obsess over the case for ten years before producing a book that probes the darkest corners of the self and unearths a tale that’s part murder mystery, part social commentary, and part memoir. (Disclaimer: McGivney and I are professional acquaintances, and I wrote a favorable blurb about Pure Land for her).

“In McGivney’s hands, both Hanamure and Wescogame are complex and deeply human characters.”

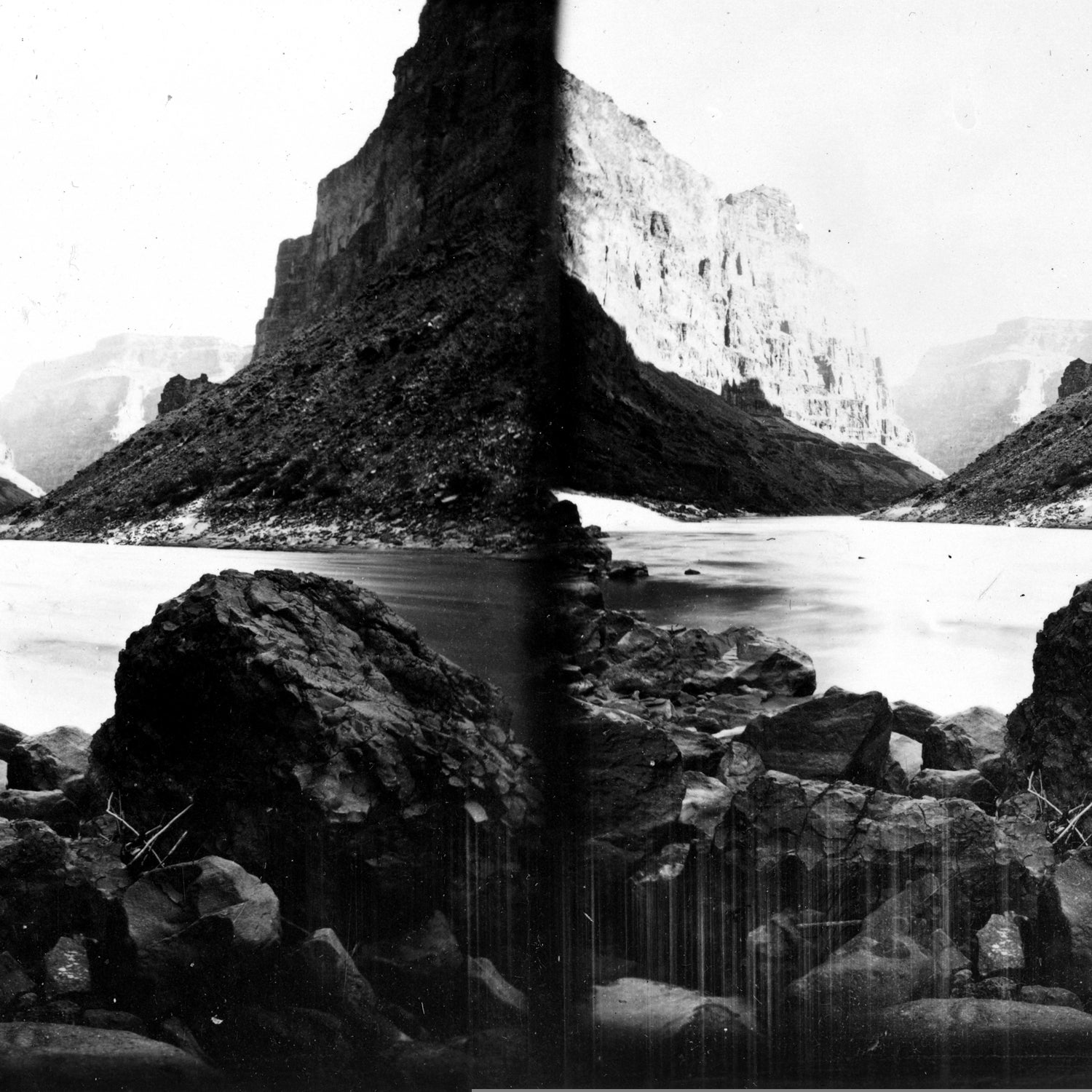

The story centers on events that took place in Grand Canyon; its cream-, ocher-, and rust-colored walls present the largest opportunity in the world to observe what lies beneath the surface. It’s the perfect metaphor for McGivney’s first-rate reporting that digs deep into the lives of Hanamure and Wecogame—and her own inner life. The chapters toggle between the three individuals. Hanamure’s storyline follows her young adulthood, travels in the United States, and search for love. Meanwhile, the book examines ancestral history, troubled youth, and descent into drugs and murder. Finally, McGivney describes her own childhood, marriage, years of caring for infirm parents, and plunge into psychological breakdown.

Yes, there’s a lot going on in this book, but McGivney makes it work. In her hands, both Hanamure and Wescogame are complex and deeply human characters. Hanamure, who idolizes Native Americans and their cultures, seems at first like an Indian-obsessed tourist. But on her multiple trips to the States, she deepens her understanding of the Native American experience much further than the average sightseer. She visits a traditional hogan on the Navajo Nation, for example, and goes on a solo trip in the dead of winter to the Little Bighorn Battlefield and the Pine Ridge Reservation.

Along the way, Hanamure falls in love with a fellow traveler (who later dumps her), adopts a mongrel (from the Pine Ridge Reservation), and aches for a mother she barely knew yet misses dearly (her father kicked her mother out when Hanamure was four). One of McGivney’s gifts is the ability to illuminate the core longing of her subjects, and by the time Hanamure is murdered, while hiking on her 34th birthday to Havasu Falls, McGivney has relayed her joys and sorrows so viscerally that I cried while reading the scene.

Cautiously, McGivney gives the same attention to Wescogame. Some readers may balk at this, but I found it fascinating. It’s easy to demonize a villain, but McGivney’s compassionate investigation of the murderer effectively conveys the depth of Native American oppression and how it can manifest in violence. She shows all the ways Wescogame is doomed by circumstance, including “genocide, slavery, starvation…and a governmental policy that seeks to strip an entire people of their cultural traditions.” McGivney also argues that the effects of this trauma can be passed through generations (a theory supported by and disputed ). Whether true or not, �±�����Dz�������’s childhood certainly contributed to his violence. Through a prison counselor, McGivney learns that the teen’s father, mother, and stepfather doled out beatings throughout his youth, hitting him with “whatever they could,” including TV cable, horse whips, and barbed wire.

McGivney told me that she had a “visceral reaction” when she learned about �±�����Dz�������’s childhood abuse. It intensified the symptoms leading to her own looming breakdown. But it’s not until about two-thirds of the way through the book that she reveals how spending all those years obsessively reporting on Hanamure and Wescogame ultimately led to the revelation of her own past trauma.

This might be jarring if you haven’t picked up on clues she’s been laying down, but it’s interesting to watch her link the three narratives together as she races toward a surprise resolution. Some readers will get bogged down in her blow-by-blow account of the road she took through residual trauma, but as someone who about child abuse, I commend McGivney for bravely exposing the lifelong damage such abuse inflicts.

I commend her, too, for writing the book she wanted to write, versus the one an agent or publisher thought would sell copies. The publisher she finally landed was the small but mighty Aquarius Press. But going small was a win for McGivney, who told me that her true freedom—as reporter, abuse survivor, and author—came when she “went rogue” and stopped worrying about who would buy her book. “Writing isn’t always about keeping people comfortable with their view of the world,” she says. “It’s about exposing readers to the truth, raising new ideas, and, perhaps, changing readers’ opinions.”

Pure Land is proof that she can do each of these things successfully, even while illuminating issues many would rather ignore. She tackles solo travel among young women (merely by zeroing in on Hanamure); the dark legacy of America’s treatment of indigenous peoples; child abuse (with its endless tendrils that never cease affecting victims); and the power of excavating and owning one’s story. The result is so gripping, so well reported, and so well told that it deserves space on the bookshelf next to major commercial successes like Krakauer’s Into the Wild and Terry Tempest Williams’ Refuge. Ultimately, it’s an example of why stories of the heart—even in our world of high-stakes, over-the-top adventure—matter most.