Women who write about the wild cannot be easily labeled. They are conservationists, scientists, and explorers; historians, poets, and novelists; ramblers, scholars, and spiritual seekers. They are hard to pin down but for their willingness to be âunladylike,â to question, and to seek.

The following list is in no way definitive, but if you want a primer on some of the best nature writing you probably havenât read yet, youâd do well to start with these 25 women. We present them in order from historical to contemporary.

Susan Fenimore Cooper

Henry David Thoreau is considered to be the father of American environmentalism, but he owes much of his philosophy to nature writers who came before himâand one writer in particular is overdue for credit. For his 1854 book , Thoreau consulted Rural Hours, written in 1850 by Susan Fenimore Cooper, daughter of novelist James Fenimore Cooper. Rural Hours is a record of a year around Cooperstown, New York, where she lived, and itâs the first American book of place-based nature observations.

Despite its anonymous publication âby a Ladyâ and Cooperâs status as an amateur naturalist, the book caught the attention of leading scientists of the time. Cooper lamented the changing landscape and anticipated concepts central to ecology when few others did. And she did so personally and lyrically: âThe varied foliage clothing in tender wreaths every naked branch, the pale mosses reviving, a thousand young plants rising above the blighted herbage of last year in cheerful succession.â Choose the 1998 of Rural Hoursâthe 1968 version cuts 40 percent of the original text and much of Cooperâs environmental commentary.

Gene Stratton-Porter

At a time when most women were homemakers, Gene Stratton-Porter was a prolific novelist, naturalist, and conservationist. She also wrote at a time when the Limberlost wetlands and swamps of her native Indiana were vanishing: 13,000 acres of this biodiverse area were drained for agriculture by 1913. Before they disappeared, Stratton-Porter captured the wetlandsâ rich habitat by setting her internationally popular fiction there. This includes two novels: (1904) and (1909), the latter of which influenced many young girls, including author Annie Dillard, profiled below, and was adapted to film four times. The self-reliant teenage heroine, Elnora, loved the outdoors, especially hunting moths. Stratton-Porter made a fortune from these romantic novels, with a stunning 10 million copies sold by 1924. She also wrote ten natural history books between 1907 and 1925. Stratton-Porter was the first American woman to form a movie and production company, Gene Stratton-Porter Productions, Inc., and used her position to help conserve parts of the Limberlands you see in Indiana today.

Mary Austin

Anyone interested in the natural history of Southern Californiaâwhat came before sprawl, smog, and Kardashiansâshould pick up Mary Austinâs 1903 classic . More than a century ago, Austin presciently captured a disappearing cultural and physical landscape: the people, plants, politics, and sense of place in Californiaâs Owens Valley. She did so ten years before the city of Los Angeles diverted the Owens River in 1913, a period in history known as the California Water Wars and immortalized in the film . Austin disregarded prescribed gender roles about how women should explore and talk about the natural world, and she did it with wit, verve, and lyricism. You can hear her wry voice here, channeling Jane Austen: âIt is the proper destiny of every considerable stream in the West to become an irrigating ditch.â She is known for writing essays, poetry, plays, and novels; for her pioneering work in science fiction; and as an advocate of indigenous cultures.

Karen Blixen-Isak Dinesen

Baroness Karen von Blixen-Finecke was also Baroness Badass: She shot lions, had a love affair with English game hunter Denys Finch Hatton, and was enamored with the idea of vultures picking her remains clean when she died. She wrote under the pen name Isak Dinesen in Danish, French, and English, including the superlative , her 1937 memoir made into a film about running a 4,000-acre coffee plantation in British East Africa, now Kenya, from 1914 to 1931. Though some readers feel that a European arrogance appears at times in her writing, she wrote with great feeling and affection about the people and landscape of the African continent: âThe sky was rarely more than pale blue or violet, with a profusion of mighty, weightless, ever-changing clouds towering up and sailing on it, but it has blue vigour in it, and at a short distance it painted the ranges of hills and the woods a fresh deep blue.â

Nan Shepherd

âItâs a grand thing, to get leave to live.â

âNan Shepherd

Men have written hundreds of mountaineering books, but who wrote one of the best? A Scottish poet and novelist named Anna âNanâ Shepherd. is her meditation on high and holy places: a walk into rather than up mountains, a caress rather than a conquer of peaks, a whisper of âletâs see closerâ rather than a testosterone-fueled bugle of âI did it!â

She writes, âOften the mountain gives itself most completely when I have no destination but have gone out merely to be with the mountain as one visits a friend, with no intention but to be with him.â Shepherd was a localist who deeply immersed herself in the Cairngorms, Scotlandâs eastern Highlands. She swam in streams, watched wildlife, and slept outdoorsâa deep engagement recounted in luminescent prose. The Living Mountain was written during World War II, when Shepherd often went âstravaiginââa Scottish term for wandering. For reasons unknown, she left the manuscript in a drawer for nearly 40 years. It was published late in her life, in 1977. Today, Shepherdâs writing is justifiably experiencing a renaissanceâso much so that the Royal Bank of Scotland issued a new ÂŁ5 note with her portrait in 2016.

Rachel Carson

âThe sedge is witherâd from the lake, And no birds sing.â

âJohn Keats, âLa Belle Dame sans Merciâ

Rachel Carsonâs day job was in marine biology, and she wrote the prize-winning book (1951), which spent 86 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list. But Carson is best known for her 1961 book, , which directly led to the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency. With a title inspired by a Keats poem, Silent Spring originated when dead birds began turning up in the garden of one of Carsonâs friends after rampant spraying of the pesticide DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane). A landmark in the environmental movement, Carsonâs book demonstrated the harmful environmental effects of pesticides including DDT, leading to its ban. In the book, she asks, âWhy should we tolerate a diet of weak poisons, a home of insipid surroundings, a circle of acquaintance who are not quite our enemies, the noise of motors with just enough relief to prevent insanity? Who would want to live in a world which is just not quite fatal?â In 2006, Discover named Silent Spring one of the 25 greatest science books of all time.

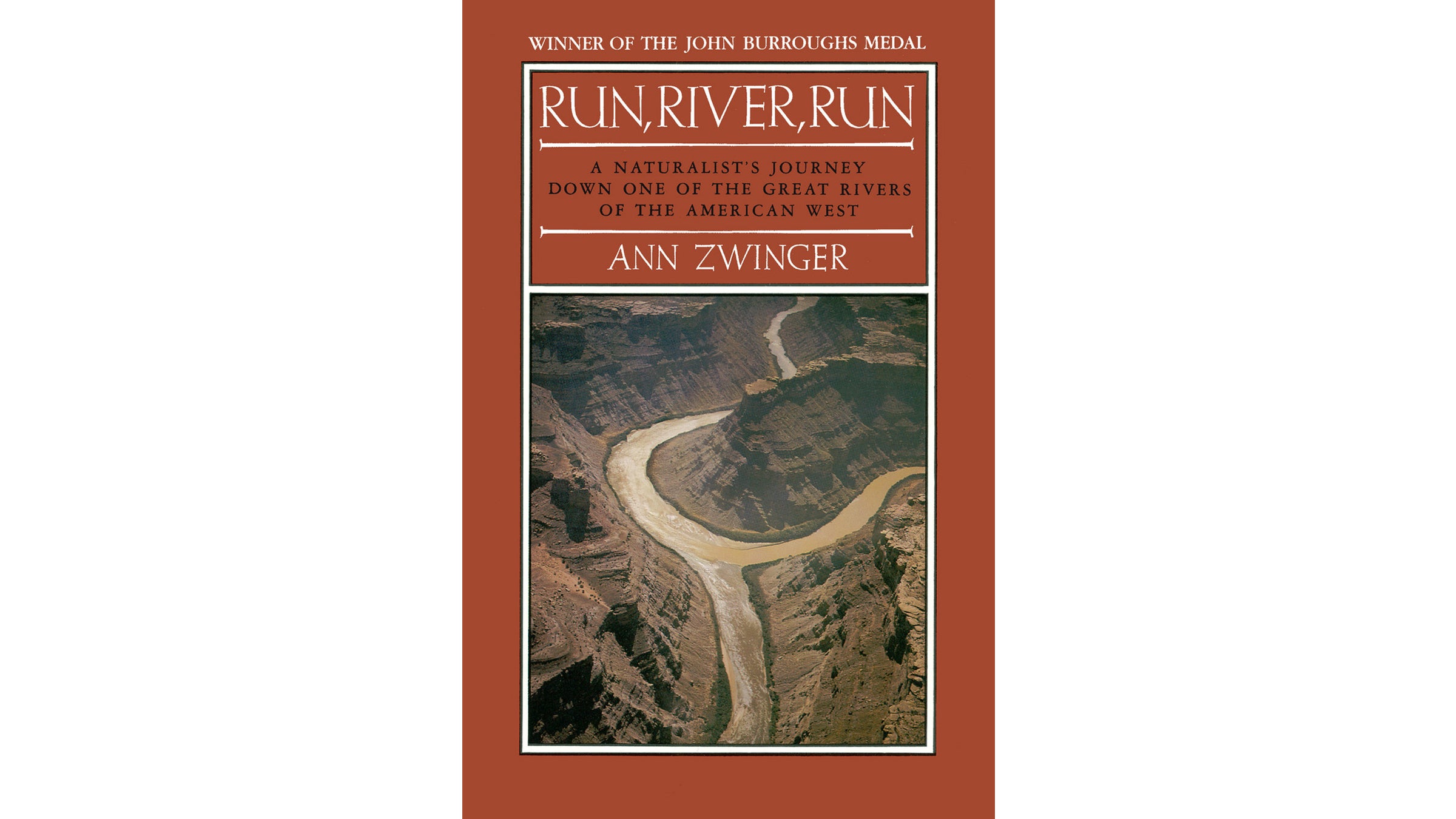

Ann Haymond Zwinger

Ann Haymond Zwinger was studying for a doctorate at Harvard when she met her husband, an Air Force pilot. As a military wife, she raised three daughters during their transfers around the country, finally settling down in Colorado Springs in 1960. When the couple bought 40 acres, Zwinger started cataloging and illustrating plants she discovered thereâthe beginning of a career writing natural histories of mountains, rivers, deserts, and canyon lands of the American West. Over 30 years, she wrote more than 20 books about her quiet observations of the wild. Meticulous and graceful, Zwingerâs writing integrated geology, botany, archaeology, and history along with personal reflections. Start by reading her 1975 book, . Youâll feel as if youâre in the boat with her: âRaw, open sand dunes spread over the right bank, white prickly poppy and masses of yellow mustard and sand-verbena blooming across them.â

Annie Dillard

You feel as though youâre sleepwalking through life. You decide you need to get off the grid. As you head for the solitude of a cabin, bring by Annie Dillard. It is, like Thoreauâs Walden, a âmeteorological journal of [her] mindâ (in her own words), a meditation, and a nonfiction book about seeing the world more intimately. At age 29, Dillard won a Pulitzer Prize for Pilgrim, and the book remains one of the finest in nature narratives. What sets Dillard apart is her desire to behold the sacred and divine along a creek in the Virginia woods. She observes her own way of seeing in poetic, scientific, mystical ways: âI had been my whole life a bell, and never knew it until at that moment I was lifted and struck.â Edward Abbey called Dillard the âtrue heir of the Masterâ (Thoreau), and she has been compared to Gerard Manly Hopkins, Virginia Woolf, John Donne, and William Blake.

Alison Hawthorne Deming

âWhat it takes to dazzle us, masters of dazzle, all of us here together at the top of the world, is a night without neon or mercury lamps.â

ââMt. Lemmon, Steward Observatory, 1990â

Descended from the great American writer Nathaniel Hawthorne, Alison Hawthorne Deming is a rare interdisciplinary cross-thinker: a poet who writes about science. From the miniscule to the stellar, she explores science, the physical world, and poetry with exquisite observations and memorable juxtapositions. With seven volumes of poetry and five collections of essays, there is no one best place to begin exploring her work, though the essay âScience and Poetry: A View from the Divideâ is a good one. As the title suggests, it coalesces Demingâs thinking about the creative process and shared language of the two disciplines. Also good: (2001), in which she writes passionately about the importance of nature writing in reconnecting people to the natural world and enhancing our spiritual lives, and her most recent work, (2016), a collection of poems reflecting on the loss of her mother and brother.

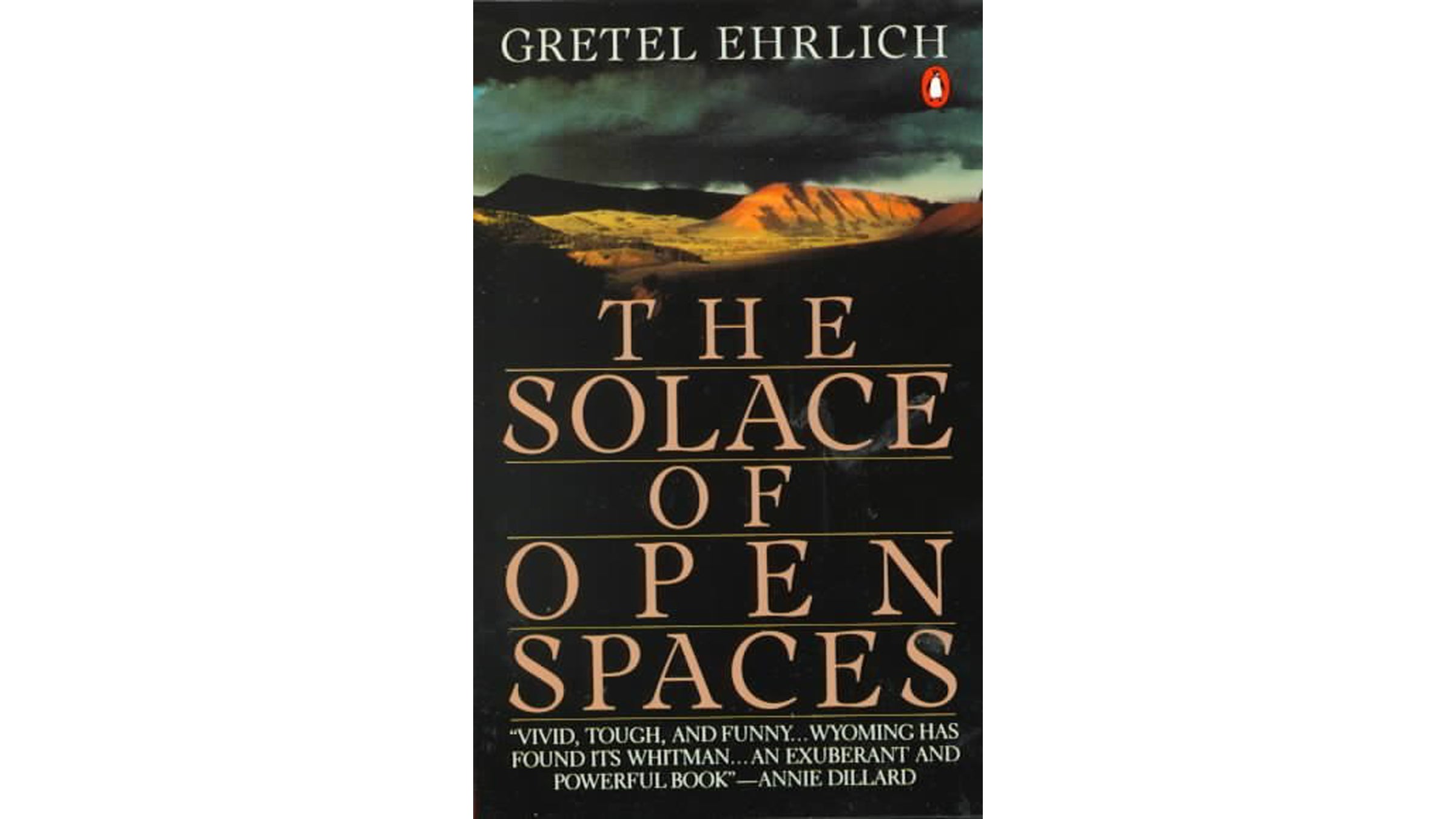

Gretel Ehrlich

Gretel Ehrlich debuted in 1985 with . It is a bareback, elegant collection of essaysâa mix of memoir, meditation, and poetryâset in Wyoming and capturing the stoic people who call the arid landscape home. After the death of the man she loves, Ehrlich throws herself into hard ranch workâdelivering lambs and calves, punching cattle, learning to ride. You can practically smell pungent sagebrush and feel the texture of dirty sheepâs wool as she works to regain personal happiness. To herd sheep, Ehrlich observes, âis to discover a new human gear somewhere between second and reverseâa slow, steady trot of keenness with no speed.â She has a knack for describing the people and places of Wyoming with mystic expression: âThe lessons of impermanence taught me this: loss constitutes an odd kind of fullness; despair empties into an unquenchable appetite for life.â Ehrlichâs 11 other books shimmer with a keen perspective on travel and place, including her 1991 narrative nonfiction, âten essays on ritual, nature and philosophyâand (1994), an unsentimental account of healing after being struck by lightning.

Kathleen Norris

âNature, in Dakota, can indeed be an experience of the Holy.â

Donât shut the book if you feel a prairie wind blow through you while reading by poet and essayist Kathleen Norris. It may happen. The book is a prairie-based spiritual meditation about learning to see more in less. In 1974, Norris and her husband moved from New York City to her grandparentâs farm in isolated Lemmon, South Dakota, where she discovers a community of Benedictine monks and revives her Protestant faith. âMaybe the desert wisdom of the Dakotas can teach us to love anyway, to love what is dying, in the face of death, and not pretend that things are other than they are.â Norrisâs spiritual quest continued beyond this book when she became a Benedictine oblate in 1986 and wrote in 1997 and in 1999.

Diane Ackerman

A grad school friend once argued, âDiane Ackerman is just too lush.â And I said, âThatâs precisely why Iâd like her.â If youâre in the mood for a velvety, layered wine by someone who revels in playing with language as much as writing about the physical world, reach for Ackermanâs books. One of the finest narrative nonfiction writers (you may know her bestselling book or Pulitzer finalist ), Ackerman also ponders diverse subjects in natural history. In , she encourages readers to see the common with fresh eyes: âDonât think of night as the absence of day; think of it as a kind of freedom. Turned away from our sun, we see the dawning of far flung galaxies. We are no longer blinded to the star coated universe we inhabit.â

Leslie Marmon Silko

Leslie Marmon Silkoâs is the story of a shell-shocked World War II veteran trying to regain his peace of mind. When first published in 1977, it deeply resonated with returning Vietnam vets and has gained more relevance as mental health and post-traumatic stress syndrome in vets is better understood. The story follows Tayo, a vet of mixed Laguna-white ancestry who has returned home to his reservation, having lost his will to live after enduring the 65-mile Bataan Death March and a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp. Alternating between prose and poetry, the book tells the events of Tayoâs life and shows how ancient Laguna rituals reconnect him to his Pueblo people, plants, and animals. Silko is regarded as the premiere figure in the Native American Renaissance. A Laguna Pueblo, Mexican, and white storyteller, she infuses all her workânovels, poems, films, short stories, and essaysâwith concerns for traditional Native American culture and the restorative power of ancient rituals. Raised in the sparse beauty of a New Mexican plateau and a debut recipient of a MacArthur Genius Award in 1981, Silko deftly explores complex relationships between humans and nature.

Robin Wall Kimmerer

Robin Wall Kimmerer blends her scientific understanding as a professor of environmental and forest biology with her heritage as a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. Her first book, , won the prestigious John Burroughs Medal for nature writing. Her second, , won the Sigurd F. Olsen Nature Writing Award. In both books, Kimmerer weaves close observations of nature with indigenous views that invite us to reflect on our relationship with plants, animals, and the landââan ancient conversation between mosses and rocks … About light and shadow and the drift of continents … an interface of immensity and minuteness, of past and present, softness and hardness, stillness and vibrancy.â Kimmerer manages to invoke ecological spirituality while never veering toward unsubstantiated facts (thatâs the scientist in her).

Amy Stewart

Earthworms, wicked bugs, deadly plants. The flower industry. Botanical ingredients of the worldâs great drinks. These are subjects of Amy Stewartâs bestselling books. For Stewart, a Texas transplant in California with a trademark wit, the story of the natural world is the grandest and most important human story. âOur quest to understand the natural world, to preserve it, and even to profit from it and make use of it, is in some ways the only story,â Stewart said in an email exchange. A personal favorite of mine is , filled with liqueur recipes and horticultural history. We learn how to plant citrus and sloes, and how to make a sloe gin fizz or a red lion hybrid. Itâs neither easy nor recommended, but I now plant my garden with a cocktail glass in one hand and a spade in the other.

Carolyn Finney

What percentage of visitors to Americaâs national parks are black? Seven percent, according to a survey commissioned by the National Park Service. If black people comprise twice that percentage of the U.S. population, why donât more people of color venture into Americaâs public lands, and does that mean they arenât engaged with the natural environment? These are potent questions of race, identity, and connection that Carolyn Finney, a writer, performer, and cultural geographer, addresses in her 2014 book, . A mixture of scholarship, memoir, and history, the book is an academic yet probing read, braiding analysis with interviews to trace the environmental legacy of slavery, racial violence, and Jim Crow segregation while also celebrating contributions black Americans have made to the environment.

Terry Tempest Williams

âI am slowly, painfully discovering that my refuge is not found in my mother, my grandmother, of even the birds of Bear River. My refuge exists in my capacity to love. If I can learn to love death then I can begin to find refuge in change.â

By 1994, nine members of Terry Tempest Williamsâs family had undergone mastectomies. Seven died of cancer. In , her sixth book, Williams weaves memoir and natural history to tell the dual narrative of her motherâs cancer from atomic testing and the flooding of the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge. Rooted in the sprawling landscape of her native Utah, the book pivots between the natural and unnatural, between a family devastated by exposure to 1950s atomic bomb testing and a bird refuge despoiled by developers. And she writes in such a shimmering manner that decades after reading Refuge for the first time, I can still see the egrets, owls, and herons on the Great Salt Lake. Itâs also there that Williams once found a dead swan, placed its body in the shape of a crucifix with two black stones over the eyes, and wrote, âUsing my own saliva as my mother and grandmother had done to wash my face, I washed the swanâs black bill and feet until they shone like patent leather.â Refuge has become a classic of American nature writing in its meditative search for meaning in the rhythms of life and death.

Janisse Ray

âMy homeland is about as ugly as a place gets,â writes Janisse Ray at the beginning of her first book, (2000). That home was a junkyard in rural southern Georgia, where Ray writes about growing up in a poor, white, fundamentalist Christian family. Itâs also a book about the longleaf pine ecosystem, 99 percent of which is gone. Ray mourns the apocalyptic deforestation of these pines, a valuable tree to merchants and the U.S. Navy. It grew from Virginia to Florida to Texas and has been replaced by faster-growing commercial pines. The author of six books, Ray focuses her work on rural life, agriculture, human rights, and environmental sustainability. What sets her apart as a nature writer? âSoutherners in general have a deep relationship with land, history, and place,â Ray said. âWhich makes nature very important to the Southern psyche. Because of the terrain, our emphasis is more botanic than geologic, more rural than urban, and more deeply rooted in story rather than statistic, generally speaking.â

Helen MacDonald

âVast flocks of fieldfares netted the sky, turning it to something strangely like a sixteenth-century sleeve sewn with pearls.â

By page 50 of , savoring each sentence like pearls on a string, you realize youâre holding a new classic in nature writing. H is the third book for Helen MacDonald, a British poet, illustrator, falconer, and historian. Her first, (2001), is a collection of poetry, and her second, (2006), is nonfictionâand it didnât just put her on the map, but rocketed her to international acclaim. The book masterfully chronicles the collapse of reality when MacDonaldâs father, who shared her passion for birding, unexpectedly dies on a London street. To deal with her grief, she throws herself into taming and training a goshawk, a bird she calls âa Victorian melodramaâ and âas muscled as a pit bull, and intimidating as hell.â Taking seven years to write, H is, simply, a masterpiece. It also stands apart from much nature writing genre for its dark, sweary, and funny bitsâtraits practitioners of more traditional nature writing often shy away from, but shouldnât. What can we expect next from MacDonald? She hasnât decided yet. âWhatever it will be,â she told me, âI think it will build on one of the deepest themes in H Is for Hawk: investigating how we unconsciously use the natural world as a mirror of our own selves and concerns, and how this relates to the way we give value to particular landscapes and creatures.â

Camille T. Dungy

âI am never not thinking about nature,â Camille T. Dungy wrote in an email, âbecause I donât understand a way we can be honest about who we are without understanding that we are nature.â A professor at Colorado State University, Dungy has written four poetry collections and edited (2009). This widely influential anthology features nearly 200 poems, from 18th-century slave Phillis Wheatley to recent poet laureate Rita Dove. It challenges the notion that the tradition of nature writing has been solely grounded in the pastoral or wild landscapes of America and Europe. The voices within the collection show nature as a devastating legacy of slavery, with people forced to work the land; at the same time, portraits emerge of writers who saw nature as a source of hope, with seeds of survival. Dungyâs poetry is vivid, personal, and lucid and stays with you long after you close the book. The poem âTrophic Cascadeâ appears to be about a changing ecosystem after the introduction of wolves to Yellowstone, but the last lines deliver a curveball: âAll this life born from one hungry animal, this whole, new landscape, the course of the river changed, I know this. I reintroduced myself to myself, this time a mother. After which, nothing was ever the same.â Her debut collection of personal essays, , was published in June.

Andrea Wulf

âAll my books are about the relationship between humankind and nature,â said Andrea Wulf, a historian and writer living in Britain. âI dislike the categories that are imposed upon books, such as âbiography,â âhistory of science,â âgarden history,â or ânature writing.â I hope that we can transcend these artificial boundaries.â A prize-winning writer, Wulf is the author of five natural history books, including (2008) and (2012). It is her detailed and arresting 2015 book, , that has garnered the most attention. Wulf pulls the explorer von Humboldt from oblivion and writes in great depth about why his ideas were so astonishing in the mid-19th century yet commonplace now: âIt is almost as though his ideas have become so manifest that the man behind them has disappeared.â

Katharine Norbury

Following a miscarriage, a breast cancer diagnosis, and a letter from her birth mother, English writer and film editor Katharine Norbury set out on a journey: to follow rivers from sea to source in the Llyn Peninsula of Northwest Wales in the company of her nine-year-old daughter. This walking journey was meant to be a kind of family memory book that Norbury felt she might bind with leaves and shells, but it grew into an exquisite and profound reflection on the healing power of nature during times of grief and loss. is Norburyâs life-affirming personal narrative about marriage, motherhood, adoption, and self-discovery. Part travelogue and healing meditation, Norburyâs place writing is lush, sensual, and vivid: âEach retreating wave was an apnoeic gasp, gravel lungs filled with water, drowning without panic.â Her next bookâuntitled as of yetâis about the circus and belonging.

Melissa Harrison

The British are obsessed with walking, weather, and the countryside. Itâs not surprising that a very good book about moody mists, damp drizzles, and downright deluges would be widely embraced and showered with praise. That book is (2016) by English novelist and journalist Melissa Harrison. A patient and poetic guide, she invites readers to explore and reimagine one of the essential elements of our world, reminding us that to âexperience the countryside on fair days and never foul is to understand only half its story.â Her third book, Rain, was nominated for the Wainwright Prize, an award given to the best writing on the outdoors, nature, and UK-based travel writing. Harrison has also written two nature novels: (2013) and (2015), the latter shortlisted for the Costa Novel Award. Hawthorn examines old secrets and a crumbling marriage against the unchanging backdrop of nature: âHe remembered the graceful elms,â she writes. âSo did the rooks, you could hear the loss of them in their chatter still. Things didnât always turn out as you feared, though; the countryside was still full of saplings, but fugitive, sheltered in hedgerows and abetted by taller trees.â

Elena Passarello

A poet, professor, and actor, Elena Passarello is one of the finest essayists working today. Her second book, Animals Strike Curious Poses, is an exquisite collection of 16 essays weaving human and animal history together in narrative nonfiction that is playful, poignant, and deeply researched. Readers of this book as well as her first, (2013), will not be surprised to learn that Passarello is a recipient of the Whiting Award for Nonfiction, a literary prize given to emerging writers with great promise. In , she takes us on a journey to a breathtaking range of places: the imagined mindset of an âendlingâ (the last of a species), the seemingly lost âcrucial glanceâ between humans and wild animals, and her own childhood memories of âLancelot the Living Unicorn.â In typical good humor, Passarello told me she brings to the practice of nature writing âa laypersonâs sense of uncertainty, wonder, and often wrongheadedness.â What fascinates her is the nature of human thought and obsession, be it a song, a speech, or a salamander. âThatâs why Iâm as likely to write about the social practices of birdwatchers as I am the birds they seek.â Whatâs she writing now? Passarello said her next venture will take her outside âto do something a little crazy, something for which I have to undergo training.â Watch for it.

Amy Liptrot

After years of hedonism and drowning in booze in London, Amy Liptrot washes ashore on her native Orkney Islands in Scotland to try to save herself. Her debut book, âwinner of the 2016 Wainwright Prize for best nature, travel, and outdoor writingâis raw and beautiful, a painful rehab memoir. It follows Liptrotâs recovery and reconnection with the landscape she sought to escape for years. In atmospheric writing, she describes swimming in the cold sea, tracking puffins and arctic terns, and observing the night sky: âIâve swapped disco lights for celestial lights but Iâm still surrounded by dancers. I am orbited by 67 moons.â The best descriptive writers have close, repeated observations of particular place; Liptrot watches tides, winds, clouds, wildlife, and more. Learning folklore and rural traditions of the islands also enhances her new, celebratory sense of place.