The Biomechatronic Man

MIT research scientist Hugh Herr lost both legs below the knee after a 1982 winter climbing ordeal. In less than a year, he hacked his prosthetics to allow him to climb again, and he went on to become one of the world’s leading innovators in the field. Author Todd Balf, who lost partial use of his legs after a spinal-cord injury, gets a front-row seat as Herr and his MIT colleagues plot their next big act—new science and technology to end a slate of disabling conditions.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

I can see him in his glass-fronted Cambridge office from the foosball table in the light-filled central atrium. He’s standing there talking to a visitor and seems to be finishing up. This entire side of the third floor in MIT’s new building is partitioned with glass, and professor and his colleagues and whatever madness they’re up to in their offices and the open, gadget-filled, lower-floor lab are on display. Several people, myself included, are peering down, hoping to see a bit of magic.

Months ago, when I e-mailed Herr to propose writing an article about him, I told him about my rare bone cancer and resulting partial paralysis below the waist as a way to explain my interest in his work. Though I didn’t tell him this, I also harbored a secret wish that he could help me. People write to Herr, a 52-year-old engineer and biophysicist, daily about his inspiring example. They’ve heard him promise an end to disability. They have conditions that medicine can’t fix and futures they can’t stand to consider. They’re wishing for his intervention, wanting of hope. Crossing his threshold, I’m the lucky one. I’m here.

for your iPhone to listen to more longform titles.

Herr welcomes me into his office, a clean, well-ordered space. There’s a round glass table with a laptop on it, a handful of hard office chairs, and a pair of prosthetic legs Herr designed that are arranged like statuary behind us, one in either corner. Above us on a wall looms a large mounted photograph of another pair of prosthetics. These are hand-carved from solid ash, with vines and flowers and six-inch heels. The real-life legs were famously worn by a friend of Herr’s, the amputee track-and-field athlete and actress Aimee Mullins.

I have hobbled into Herr’s office with a dented $20 stock metal cane on one side and a foot-lifting Blue Rocker brace on the other. (The dent is from my recently firing the cane at the wall.) I had imagined Herr noticing the cane and asking more about my story to see how he could fix me, like he has fixed so many others. The moment I realize that the meeting I’d imagined isn’t the meeting we’re going to have—I’m here as a reporter, not a friend or patient, after all—I start to stammer. Herr deftly resets the conversation by suggesting we look at his computer.

On it are the PowerPoint slides of his next big project, a breathtaking $100 million, five-year proposal focused on paralysis, depression, amputation, epilepsy, and Parkinson’s disease. Herr is still trying to raise the money, and the work will be funneled through his new brainchild, MIT’s , a team of faculty and researchers assembled in 2014 that he codirects. After exploring various interventions for each condition, Herr and his colleagues will apply to the FDA to conduct human trials. One to-be-explored intervention in the brain might, with the right molecular knobs turned, augment empathy. “If we increase human empathy by 30 percent, would we still have war?” Herr asks. “We may not.”

As he continues with the presentation he’s been giving to technologists, engineers, health researchers, and potential donors—last December alone, he keynoted in Dubai, Istanbul, and Las Vegas—each revolutionary intervention he mentions yields a boyish grin and a look that affirms: Yes, you heard that right. In a talk I hear him give a few weeks later, he’ll dare to characterize incurable paralysis as “low-hanging fruit.” In his outspoken willingness to fix everything, even things that some argue should be left alone, he knows how he sounds. “If half the audience is frightened and the other half is intrigued, I know I’ve done a good job,” he says.

Herr calmly ticks off one condition after another. He shows me an animation of an innovative surgery that will restore an amputee’s lost proprioception, giving a person the ability to feel and control a prosthetic as if it were their own limb. In another slide, of a paralyzed man in a bulky walk-assisting exoskeleton suit, he asks me to imagine a futuristic treatment that uses light to control cells in muscle tissue. Then he presents a video clip of a rat with a severed spinal cord dragging around its paralyzed hind legs.

Having dragged my mostly unresponsive left leg around for two years, I think I know something about the rodent’s life. In the next clip, however, that rat, just 90 days later, is walking on all fours. A team at the MIT center led by Herr’s colleague Robert Langer successfully regrew the rat’s spinal cord by implanting a dissolvable scaffold seeded with neural stem cells. In Herr’s world, the limbless can be whole again, the paralyzed can walk. Making the extraordinary seem ordinary is maybe the whole point.

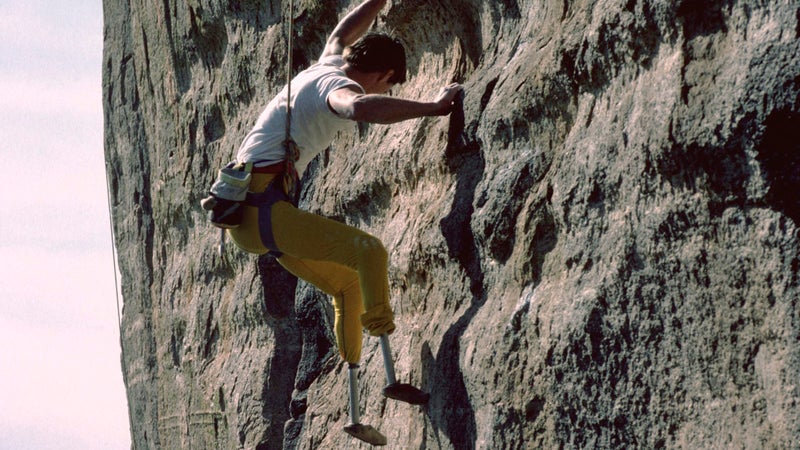

Herr himself is proof positive. Trim, fit, and handsome, he is the showpiece for the Center for Extreme Bionics. “I’m kind of what they’re selling,” he says. The fuss over Herr has been building for decades but reached new levels in 2014, courtesy of , which has now been viewed in excess of 7.3 million times. In it, Herr describes the horrific 1982 winter climbing accident in New Hampshire’s White Mountains during which he suffered severe frostbite, leading to the amputation of both legs below the knee. Then 17, Herr was told he’d never climb again. Instead, he rebuilt himself almost immediately, willfully reshaping his artificial legs and realizing that he wasn’t handicapped, “the technology was.”

By hacking his prosthetic devices for his “vertical world,” he was able to quickly return to climbing, becoming the first athlete—decades before Oscar Pistorius—to blur the line between para and not. His accomplishments landed him on the cover of ���ϳԹ��� a year after his accident, something that sticks with him not because of the many accolades other climbers bestowed on him, or even the controversy it reignited around the tragic death of one of his rescuers, but because of the questions the article raised about how far Herr would be able to go. “I was a sad case. I was going to end up in this machine shop, disabled,” Herr recalls of the piece, pausing to let the perceived insult ripen in his mind. “Yeah, it’s a real sad story.”

The triumphant, fully realized man in the TED Talk is a marvel. His outrage at the unnecessary suffering from disability is fiercely personal. What first-time viewers like me invariably fixate on is the way Herr gracefully owns the stage. He’s wearing pants that end above the knee, revealing shimmering high-tech silver and black prosthetics. Herr is focused on what he’s saying, not what his artificial legs are doing. The crime of physical impairment is that it often steals from a person’s sense of self. If you didn’t look below his knees, you’d never guess that Herr is missing half of each leg. He walks through the world the way we all would hope to.

He has effectively ended his disability, or at least the perception of it, just as he said he would. Inspired by his accident, he earned a master’s degree in mechanical engineering at MIT in 1993, followed by a Ph.D. at Harvard in biophysics. Ever since, Herr has produced a string of breakthrough products, starting with a computer-controlled artificial knee in 2003. In 2004, he created the at MIT, a now 40-person R&D lab drawing on the fields of biology, mechanics, and electronics to restore function to those who’ve lost it. Three years later, the team produced a powered ankle-foot prosthesis that allows an amputee to walk with speed and effort comparable to those with biological legs. Called the emPower, the apparatus weighs a few pounds and houses 12 sensors, three computers, tensioning springs, and muscle-tendon actuators. The ankle system is manufactured by a private company Herr started called .

If you didn’t look below his knees, you’d never guess that Herr is missing half of each leg. He walks through the world the way we all would hope to.

Last year, Herr advanced another of his lab’s goals, to improve human performance “beyond what nature intends” by creating a brace-like exoskeleton device that reduces the metabolic cost of walking. The implications for people who want to get places faster—or perhaps a soldier trying to conserve energy on a long march—are vast.

In the near future, Herr and his colleagues at the MIT center are committed to, among other things, reversing paralysis. Herr’s goal is to develop a synthetic spinal cord that

aids the damaged original. A prosthesis, in other words.

In his office, Herr draws up his pant leg and rolls down a silicone sleeve to show me a newly developed fabric that lines the socket of his prosthetic and cushions the problematic intersection between the biological stump and the man-made limb. The “exquisitely comfortable” fit—digitally derived, he explains, but highly personal—is something he delights over with a savoring gush.

With our first meeting nearing its end, I grow distracted thinking about the wounded few Herr has smiled upon. In 2014, he worked on a bionic prosthetic for the dancer Adrianne Haslet-Davis, who lost her left leg in the Boston Marathon bombing. Currently, he’s working with Hari Budha Magar, a double-amputee former Gurkha soldier who plans to climb Mount Everest in 2018, and also Jim Ewing, an old New Hampshire climbing buddy. Ewing was climbing a wall on vacation in the Cayman Islands in 2014 when he fell with his teen daughter on belay. She couldn’t brake the rope, and he plummeted some 60 feet, shattering his pelvis and left foot on impact.

The dancer, the Gurkha, the climber, and Herr himself are examples of what he often describes as the millions of humans who might appear broken but are not. Haslet-Davis, on a bionic limb embedded with dance intelligence, brilliantly performed the rumba again, and Ewing underwent a pioneering amputation procedure developed by Herr’s biomechatronics team in partnership with MIT colleague and surgeon Matthew Carty, who performed the operation at Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital, to prepare Ewing for an advanced prosthesis. Magar will be outfitted with short prosthetics to reduce leg drag and sophisticated crutches for speed as he attempts Everest history.

The stories Herr tells, the future he sees, the beautifully functioning artificial limb before me—it’s all I can do not to show him my atrophied left leg and ask for his godlike intervention to fix what I know is broken. But I don’t, not yet.

When I wrote Herr to tell him about my interest in his work, I summarized my case history. I explained how in the summer of 2014, I found myself with increasingly debilitating nerve and lower-back pain. When I finally got an MRI, I learned that I had an extremely rare bone cancer called chordoma that had spread from my lower lumbar vertebrae into my right hip flexor. Radiation and a difficult multi-stage surgery successfully removed the softball-size tumor, but months later, possibly due to a loss of blood to the spinal cord, I’d yet to regain sensation or strength in my hips and legs. The doctors didn’t know if it was permanent, but the prognosis didn’t look good.

I’d expected a rapid, maybe even exceptional recovery. I am an athlete and adventurer who has had the good fortune to do a lot of cool stuff over the years. I’d become a whitewater guide, climbed Grand Teton, raced the hill climb at Mount Washington on foot and by bike, and mountain-biked half the 3,000-mile-plus Great Divide route. I expected to complete the other half someday.

I’d progressed from a walker to a cane, from a recumbent tricycle to a pedal-assist e-bike. Then my nerve regeneration halted. In May 2015, after the surgery, I’d contacted Boston neurologist Bill David for muscle and nerve testing. An avid cyclist and kindred spirit, he’d hopefully stuck needles into my skin every six months to chart my recovery. Late last year, he confirmed what I had already sensed. Short of a miracle, I’d gone about as far as I could. “I really wish that we had met on a mountain or river as opposed to a medical clinic,” David said.

I’d negotiated several stages of recovery, but the one I feared most was right now—at the end, my future fixed. “I’ve been coming to grips with who I am as an ‘incomplete’ paraplegic and figuring out how to make the best version of this new person,” I wrote

to Herr.

I’d imagined a stirring epilogue to our encounters, a moment perhaps when a radical trial arose and a crazy volunteer was needed. To be closer to the person I once was, I would try anything—injected viruses, exoskeletal suits, implants. When I got together with a close friend for lunch, I told her how the story with Herr was progressing, and how the limbs he created were so advanced that I’d read about people wanting them even though their leg complications didn’t medically require amputation. She listened carefully. “Let me ask you something,” she said. “Would you, um, get your legs cut off?”

Exactly when in his childhood Hugh Herr decided to become the world’s best climber is impossible to pinpoint, but the goal was nurtured during family road trips across the West. He and his older brothers climbed, fished, and hiked in the American and Canadian Rockies, whetting the youthful Herr’s appetite for adventure. The Shawangunk Mountains in New York were a four-and-a-half-hour drive from the Herrs’ home in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. The Gunks were an emerging mecca in the seventies, and Herr quickly established himself as a prodigy, “climbing this stuff when I was 11 that only adults had done, and at 15 that no one else had done,” he says.

When he and Jeff Batzer, a friend from Lancaster, drove to New Hampshire’s Mount Washington in January 1982 for a weekend ice-climbing outing, it wasn’t to do anything audacious. They’d attempt a classic route in Huntington’s Ravine, and maybe, depending on the weather and avalanche conditions, summit Mount Washington before racing down for the 12-hour drive home. Herr was a 17-year-old junior in high school, his friend Batzer, 20.

I told a friend how the limbs Herr created were so advanced that I’d read about people wanting them even though their leg complications didn’t medically require amputation. She listened carefully. “Let me ask you something,” she said. “Would you, um, get your legs cut off?”

The decision to tack on the summit of Washington turned out to be a tragic mistake. They left a sleeping bag and bivy sack behind to reduce weight but encountered howling winds and blizzard conditions near the top, and they ended up losing their way, mistakenly descending into a different valley from where they’d come.

After four days trekking through a storm in deep snow and below-freezing temperatures to find their way out, Herr was no longer able to walk. Early on in the odyssey, he had punched through a frozen streambed into shin-deep water, soaking his boots and pants, and was suffering from severe frostbite. In , a biography by Alison Osius, Herr said that he had reconciled himself to death when a backcountry snowshoer saw some of Batzer’s tracks and followed them to a makeshift shelter the two were bivouacked in. The climbers were evacuated to a nearby hospital in Littleton, where doctors treated both for hypothermia and frostbite. Herr’s legs were in terrible shape. At the hospital, he learned that doctors might not be able to save them and that a member of his search party, a 28-year-old climbing-school instructor named Albert Dow, had been killed in an avalanche. Two months later, doctors amputated Herr’s legs four inches below the knee. Batzer’s fingers on his right hand were amputated, along with his left foot and the toes on his right foot.

“I asked my doctor after the amputation what I’d be able to do with my new body,” Herr recalls. “The doctor said, ‘What do you want to do?’ I said I wanted to drive a car, ride my bike, and climb. The doctor said you’ll be able to drive a car, but with hand controls. He said I would not be able to ride a bike or return to climbing.”

Herr did all of the above within a year. He worked closely with his prosthetist on one pair of artificial legs after another and tinkered on his own in the machine shop of a vocational school he’d begun attending in 1981. He soon figured out that he could hack his artificial limbs to suit the requirements of particular climbing routes. He built limbs that extended or shortened his stature; he carved out feet with wedge ends to slice into crevices. He began to knock off routes that he hadn’t been able to do previously, including leading an ascent of Vandals at Skytop, the first 5.13 on the East Coast. It ignited a new controversy: that his adaptations were a form of cheating. Herr likes to tell audiences that he invited his affronted rivals to chop off their own legs.

“Some people were bitter and angry” about the accident, says Jim Ewing, a summer roommate of Herr’s in the 1980s, “and with Hugh coming back and climbing so well, they started making up excuses, saying things like, ‘He can stand on a dime, his feet don’t get sore, he doesn’t have calf fatigue.’ I’d just look at these people and think, By God, you haven’t seen this guy crawl to the toilet in the middle of the night because he doesn’t have his legs on. He is handicapped; it is a handicap. People had no idea.”

While there was a lot of media attention about Herr’s accident, he kept private the struggles and self-doubt he faced after he lost his legs. When he returned to New Hampshire to climb again 18 months later, the unease from locals over Dow’s death and Herr’s resurgence was palpable.

The harsh early views of Herr didn’t soon go away. When I asked him what he thought when the last year honored him at a celebratory awards evening in Denver, he said he was stunned. They had named him a new inductee of the Hall of Mountaineering Excellence “for lasting contributions on and off the mountain.” “It shocked me,” he said. “The initial story line of the accident was that these young, irresponsible, incompetent climbers caused the death of an experienced, beloved local climber. That narrative went on for a very long time. So for two decades at least, I wouldn’t even expect the American Alpine Club to invite me to be in the audience.”

When Herr talks about Albert Dow, who he never met, it’s with the fondness of a friend. “That was Albert!” he recounts about Dow’s insistence that he go looking for Herr and Batzer because he’d want someone to do the same for him. Last year, Herr told a Reddit audience that he strives to honor Dow. “I hate the idea that his death somehow enabled me to live so I could do good work,” he says. “What I like is that his kindness and who he was—and his sacrifice—inspired me to work really hard.”

In 1985, Herr free-climbed New Hampshire’s exceptionally steep and unprotected Stage Fright, with his friend Jim Surette on belay. It was a significant and life-threatening milestone, and afterward Herr had a dream that set his new path. He describes a nightmare in which Surette, bunking on a neighboring couch, throws off his covers to reveal mangled, bloody, amputated legs. “We both go ‘A������!’ in the dream,” says Herr, “but then I turn to Jimmy and say, ‘Don’t worry, Jimmy, it’s just a dream. I’m the one without legs.’ Prior to that, in all my dreams I would be running and jumping, and I would have my biological legs. It was the first time my brain recognized my new state.”

Some might’ve interpreted the nightmare with melancholy, an attempt to come to terms with a sorrowful lifelong condition. Herr saw it as a beautiful vision.

The auditorium is full at the Princeton, New Jersey, headquarters of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, all 150 in attendance looking stage left as Herr introduces an image of himself in a New Hampshire hospital room decades earlier. “What do you see?” he asks.

It is Herr in the moments after his legs have been amputated. The 17-year-old is gazing down at a white sheet and the outline of his stumps. The audience is riveted.

“What do you see?” he asks again. “I see a new beginning,” he declares. “I see beauty.”

Herr, who prefers to use the term �ܲ��ܲ��ܲ��� instead of handicapped or disabled, often says that he wouldn’t want his biological legs back. He loves the legs he started building after the accident and has steadily improved upon for the past several decades.

His meteoric rise in academia is almost as improbable as his comeback to elite climbing. “I actually graduated from high school not being able to take 10 percent of 100,” he says. “I had no idea what a percent was.” His older brothers were all in construction. He understood that the family trade was unavailable to him, so he shut himself away and applied the same obsessive focus to science that he’d once reserved for climbing. He read everything he could find and enrolled at the local college, Millersville University.

“Herr would put all these ideas on my blackboard, and the chalk would literally be disintegrating. He’d call me at midnight with an idea. I’ve never met anyone so committed or intense.”

“We’d watch all these films of animals locomoting to try to learn about motion,” says Don Eidam, his first adviser at Millersville and an unapologetic superfan who writes a newsletter about Herr. “He’d put all these ideas on my blackboard, and the chalk would literally be disintegrating. He’d call me at midnight with an idea. I’ve never met anyone so committed or intense.”

In 1991, Herr became the first student from Millersville to be accepted at MIT. The academic degrees, innovations, and honors have since overflowed. He is the holder or coholder of over 100 patents. The powered prosthesis he developed for ankle-foot amputees was the product of a special mind with a special motivation. By copying the behavior of a biologically intact leg, Herr and his biomechatronics lab were able to create a breakthrough replacement. In 2011, Time crowned him the “leader of the bionic age.” Last year he won Europe’s top prize for inventors, the prestigious Princess of Asturias Award.

“In Hugh’s mind, he has not successfully innovated until people are able to benefit from his innovation,” says Tyler Clites, a Harvard-MIT student who has worked in Herr’s lab for six years. “He has said to me, ‘Look, Tyler, I’ve invented hundreds of times, but I’ve only ever innovated twice.’ ” The two items, his prosthetic knee and the ankle-foot, are the only ones commercially available to others.

The idea of an endlessly upgradable human is something Herr feels in his bones. “I believe in the near future, in a decade or two, when you walk down the streets of Boston, you’ll routinely see people wearing bionic systems,” Herr told ABC News in a 2016 interview. In 100 years, he thinks the human form will be unrecognizable. The inference is that the abnormal will be normal, beauty rethought and reborn. Unusual people like Herr will have come home.

At a small luncheon after his talk in New Jersey, the organizers ask me to say a few words about my condition. I give a five-minute recap of my struggles with cancer, the spinal-cord complication, and my up-and-down recovery. It is my first time speaking publicly about my situation. As I do, I sneak a glance or two at Herr. I wonder what he thinks hearing me tell my story. He is sitting immediately to my right, raking through a towering salad.

There is no clear signal from him, but I leave feeling that I’ve pulled ever so slightly into his orbit. I am also beginning to understand the weight he bears of being a savior. A friend who saw his impassioned SXSW talk in 2015 told me how she raced up to thank him afterward, only to encounter a different guy. He was polite but aloof. She was put off, but I think I understand. The man has to set boundaries. He can’t save everybody.

You might say that Herr’s the sort of disrupter the research world needs, or you might say he’s overpromising. One spinal-cord-injury scientist I spoke with wasn’t so sure that a bold tech solution is the answer in a field long focused on the biology of nerve regeneration.

Nicholas Negroponte, the cofounder and former director of the MIT Media Lab, says Herr’s sense of humor helps him handle any negative commentary. “It’s particularly important when you do and say risky things, some of which invite harsh criticism,” he says. “You smile and keep going, because you know you’re right.”

A week after his talk in New Jersey, Herr and I meet up at a seafood restaurant near his MIT office. I arrive 30 minutes early, wanting to get situated. Having lived with my disability for some time now, I understand that I can’t just sweep in like I used to. Herr, to my surprise, given his packed schedule, arrives ten minutes early.

Herr told me earlier that he rarely pushes himself on climbs anymore. He proudly mentioned his two preteen, homeschooled daughters, who are avid hikers and spend almost every weekend with Herr’s former wife, Patricia Ellis Herr, in the White Mountains happily exhausting themselves. They long ago summited Mount Washington and have high-pointed in 46 of the 50 states.

Herr and I talk at length about some of the people he has worked with and why. The Haslet-Davis project took a group from his biomechatronics lab 200 days to create the prosthetic, counting down to the 2014 TED Talk. “She said she wanted to dance again. I really related,” he says. He told himself, I’m an MIT professor, I have resources. The timeline was tight enough that there was a TED Talk plan A (with her) and plan B (without). As everyone knows who has watched the video, Herr’s team hit its deadline. Haslet-Davis unforgettably danced again, and there wasn’t a dry eye because of it.

But as incredible as the moment was, it’s a source of frustration that the prosthetic can’t be permanently handed over to Haslet-Davis. While Herr would love to give it to her, it’s a prototype that would cost millions to reproduce. As for Herr’s climbing buddy Jim Ewing, that’s a similarly uncertain situation. Months after Ewing had his foot amputated, he was fitted with a newly designed ankle-foot prosthetic that responds to his brain waves and allows him to feel his appendage. It is also a prototype that Ewing will eventually have to return.

Haslet-Davis and Ewing understood that they were part of a research project and wouldn’t be able to keep the prototypes. Meanwhile, Herr’s knee and ankle prosthetics, which cost tens of thousands of dollars, aren’t yet widely covered by insurance and remain too expensive for most who have a need for them. Herr has been in discussions with insurers to try and change that. According to Amputee Coalition of America estimates, there are 185,000 new lowerextremity amputations annually in the U.S. By contrast, there are only 1,700 emPower ankles in circulation right now. About half of them are worn by vets, paid for through reimbursements covered by the .

“Herr’s work is important and coming from a good place,” says Alisha Sarang-Sieminski, at the Massachusetts-based Franklin W. Olin College of Engineering, a school involved in numerous projects related to lower-cost accessibility design. “But people have different needs for different contexts. Also, so much of the high tech is really not accessible to very many people financially. Should people keep building them? Definitely. Should we also explore basic solutions? Yes.”

Still, Ewing’s pioneering amputation is a huge success for Herr’s group, the Brigham and Women’s surgical team, and, most notably, Ewing. When I visited him at a climbing gym near Portland, Maine, he was planning a trip back to the Cayman Islands. For Ewing, the amputation has reduced the acute pain he used to feel in his biological foot and dramatically changed his outlook. He says that after his accident, he contemplated suicide. “Being alive isn’t enough,” he says. “Breathing isn’t enough. I had to do something. Hugh understood my motivation probably better than I did.”

Herr hadn’t seen Ewing for years when he got an e-mail from him asking for advice about his foot. “He was in a bad place,” says Herr. “Also, I really felt for his daughter. I know guilt so well, that poor girl.”

Ewing says that the way he’d set up the ropes is to blame for his daughter’s inability to brake the fall. Though she has returned to climbing at the gym and bouldering, she wasn’t interested in rope climbing in the accident’s aftermath, and Ewing worried that he’d ruined the sport—a passion they’d shared for years—for her.

Meanwhile, the gift Herr has given Ewing is exceptional. It might be the first time Herr is not the most technologically advanced lower-limb amputee. Herr often describes himself and others facing disabilities as “astronauts testing new life-enabling technologies.” As for his own legs, Herr wants to go even further but would need to leave the U.S. to undergo the operation he has in mind. “I’d love to do it,” he says, without revealing any details about the procedure. “I’m just weighing the risk. I definitely don’t want to go backwards.”

In the short term, he’s using a newly designed set of titanium legs and pushing forward on his work, noting hoped-for funding this year from the military “to show we can synthetically take over a paralyzed limb.” Herr then asks about my rehabilitation experience. This is finally my chance, I think, to ask if there’s anything he can do for me.

I tell him that I identify with amputees and often wonder how some people without legs are more adept than some of us with them. Every time I watch a person with artificial legs walking, I selfishly wonder, Why not me? Why not us? Herr says they have some good ideas but acknowledges that the field has been way more successful in the amputation arena than with spinal-cord injuries. “It’s hard,” he says.

You might say that Herr’s the sort of disrupter the research world needs, or you might say he’s overpromising.

While Herr has complete autonomy selecting projects in his lab, his interventions are rare, and they don’t happen unless the time and circumstances are right. “Often, people ask for help and I don’t have the resources or the solution,” he says. Exceptions like Haslet-Davis and Ewing come from “feeling deeply about it and being in the position to make it happen.”

I realize talking to Herr that it’s not my story that’s weak, it’s the technology. I’d incorrectly understood his comment about an imminent cure. Paralysis is “lowhanging fruit” in that it’s a condition they can impact in ten to twenty years instead of fifty. There are no toys to play with in Herr’s lab closet. Not yet.

Before Herr and I wrap up our last visit, I ask what he’d do if he were at an impasse. It’s clear, at least to me, that I’m talking about myself. Being a scientist, he focuses on process. He says he throws everything and anything at a problem. He visualizes each idea as a rock and starts turning them over. He mentions an acquaintance who came to see him earlier in the day who was struggling with depression. Herr started in, imagining at hyperspeed all the places the person might go and hadn’t yet. “Acupuncture? No? Meditation? No? Are you running? No? What medications have you tried? One? One! There’s like 20 antidepressants! Go, go, go!” he says he wanted to plead. He chuckles at his overexuberance, but his belief is real. This can be solved!

When I say goodbye to Herr and watch him bound down from the upper level of the restaurant to the rain-drenched sidewalk, I’m struck by a malaise. Maybe it’s the rain. Maybe it’s the opportunity lost. Maybe it’s the way he flipped a switch on his emPower ankle and raced effortlessly into the street. But then I think about Herr turning over one rock at a time and the span of possibilities he presented to help with depression. I’m not out of options. There are hundreds of researchers working on a paralysis cure, and I immediately think of a world map I saw recently on a website with dozens of bright red circles representing centers of innovation. I can hear the words of my neurologist, who on my last visit leaned in with something else when he said goodbye. “Keep moving,” he urged. There’s even a clinic in New Hampshire I heard about where they’ve produced exceptional walking recoveries using a robotic gait trainer available nowhere else in the U.S.

I begin to wonder, was Herr’s story about his depressed acquaintance allegorical? An on-the-spot intervention? Had I just been, ever so lightly, smiled upon, too?

Longtime ���ϳԹ��� contributor Todd Balf is the author of . is an ���ܳٲ��������contributing photographer.