The revolutionary way we now use maps in our everyday lives has, in the last decade, actually changed the physical world. Businesses succeed or fail based on their . Once quiet streets are now , for the promise of a few seconds saved. Nicaragua almost went to war with Costa Rica because of . But that only applies to street maps. Why are the maps we use outdoors still drawn from the 20th century?

If I gave you an address a few miles from your home, and asked you to meet me there without first checking your phone or computer, you probably couldn’t do it. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. While we’ve largely lost our painstakingly memorized ability to navigate streets, technology has replaced the need to, while augmenting our navigation ability to new levels. Using your phone, you’d know exactly how long it’d take to get to our meeting. You could suggest places for lunch, find parking, and even avoid developing traffic problems.

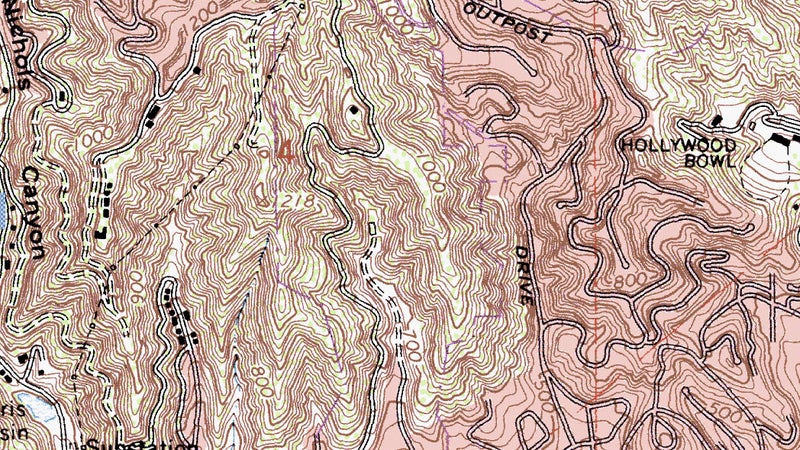

And yet, if you and I were to plan a backpacking trip together, we’d need to visit a physical store (or wait for shipping), purchase a paper topo map, and mark it up with pencils and highlighters. In the field, we’d use a compass to find our position.

Some expert users have, for years, been tracking waypoints and sharing routes and destinations through dedicated GPS devices or navigation apps on their smartphones. But that practice hasn’t approached the pervasiveness of technology in street navigation, and a few dropped pins hardly represents the true potential of what is technically possible. And it still relies on source maps that tend to be incomplete, outdated, or simply lack detailed information.

One man wants to change that.

“I was doing my first really large scale search, in a regional park outside of San Francisco and it was just a giant navigational mess,” says Matt Jacobs. He began working as a software developer in the Bay Area after graduating from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, while also volunteering for the on the side. In that first operation, the 100 plus SAR volunteers were trying to navigate by switching between an outdated topo map missing information on the trail system and trail maps that didn’t accurately show the terrain. Why couldn’t they simply use a computer to combine the two, Jacobs wondered. So he got to work.

“Initially I was just trying to find a way to take different map layers, overlay them on one another, and align them so you could build up your situational awareness,” Jacobs says. That work, which began seven years ago, eventually culminated in a website called , which now offers incredibly detailed mapping data for the Unites States, Canada, and is slowly expanding to other countries. “I just started playing around by trying to layer Google’s terrain maps with their satellite imaging, and it just sorta spiraled from there.”

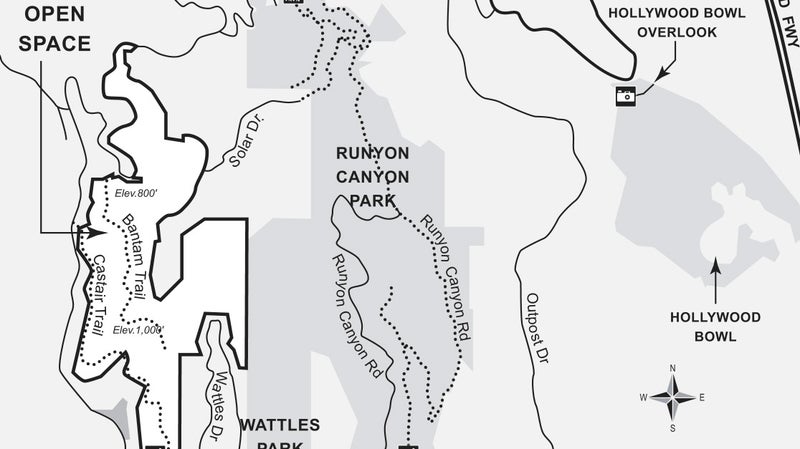

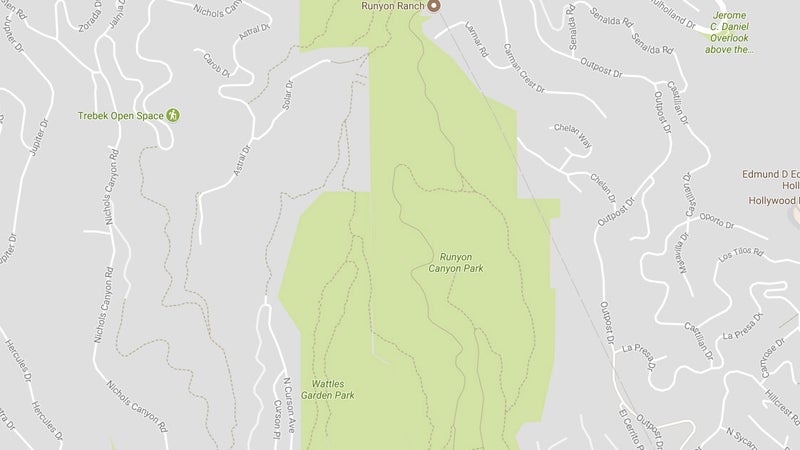

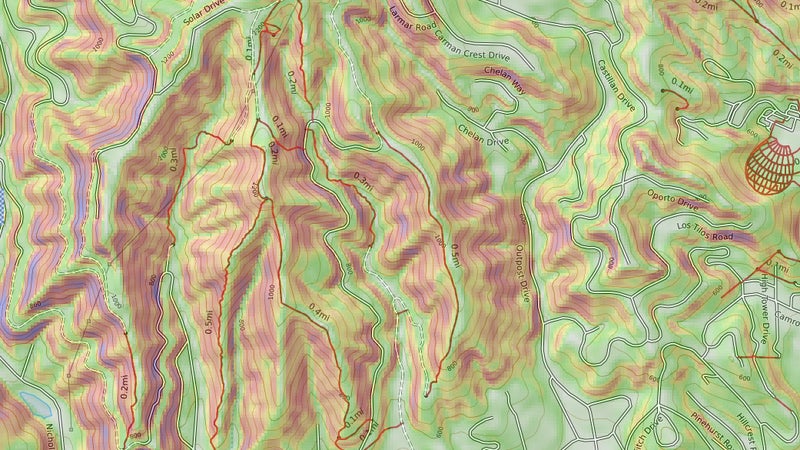

Begun as a little more than a hobby and designed to give Jacobs a useful tool, CalTopo quickly became the go-to mapping resource for BAMRU and other SAR groups in California. So he continued to develop the tool to meet their highly specialized needs. Some areas are best mapped by the Forest Service, while in others, it’s the USGS or maybe even street maps. Often, it’s by combining five or six layers of information that SAR workers are able to achieve the visual information they need to effectively navigate unknown areas with granular detail. (Jacobs rolled a lot of the SAR specific logistical stuff into a dedicated site, .)

In addition to simply layering source maps, Jacobs began building CalTopo out with impressive, SAR-specific datapoints, like viewshed analysis, which allows you to map line-of-sight radio transmissions between hilltop repeaters, and sunlight shading for dog teams. (“Dogs are very dependent on scent,” he says. “When direct sunlight hits a slope, the air tends to rise straight up, and the dogs can’t really follow the scent cone into a subject. So, you want to get them on hills before the sun hits them, or after the sun goes away.”)

That’s a lot deeper functionality than Google Maps or paper maps provide. So how can us civilians use CalTopo’s extremely deep data visualization abilities to simply go play outdoors?

One example is slope shading. Do you climb mountains or ski the backcountry? If you do, you’ll know that calculating avalanche risk is a constant necessity. Comparing map distances to contour line frequency and calculating slope angle is tricky math, especially when you’re looking at a big area. To save you that work, Caltopo offers slope shading, which simply applies a graded color scale across differing slope angles, easily highlighting any areas that may be of concern.

“I try not to sell it as, Just don’t go where it’s shaded, and you’ll avoid avalanches, but this helps you identify and avoid large-scale hazards,” says Jacobs.

Right now, Jacobs is working on adding an accurate temperature forecast layer. “I spend a lot of time playing whack-a-mole with the NOAA forecast, clicking around the map for various point forecasts, but those can be for elevations that are 2,000 feet higher or lower than what I’m looking for,” he says.

Barring other conditions, that’s a six-degree difference right there. What Jacobs is trying to develop is a colored gradient that you can lay over any map, which will display temperatures for each elevation represented. “You could highlight everything that’s going to be below freezing as the daily high, or above freezing, or whatever,” he says. This could inform you on snow or ice conditions up high or simply help you find a more comfortable spot to camp.

The product of one man’s part-time development—after seven years, Jacobs just went full time on the project—CalTopo doesn’t currently match its function with user friendliness. The problems are worse on your phone. But stick with the desktop website, find the best map layers for your upcoming trip, add some waypoints or tracks, and export the result to another app on your phone, and you’ll be rewarded with an unprecedented level of information, accessed with unprecedented ease once you leave cell signal behind.

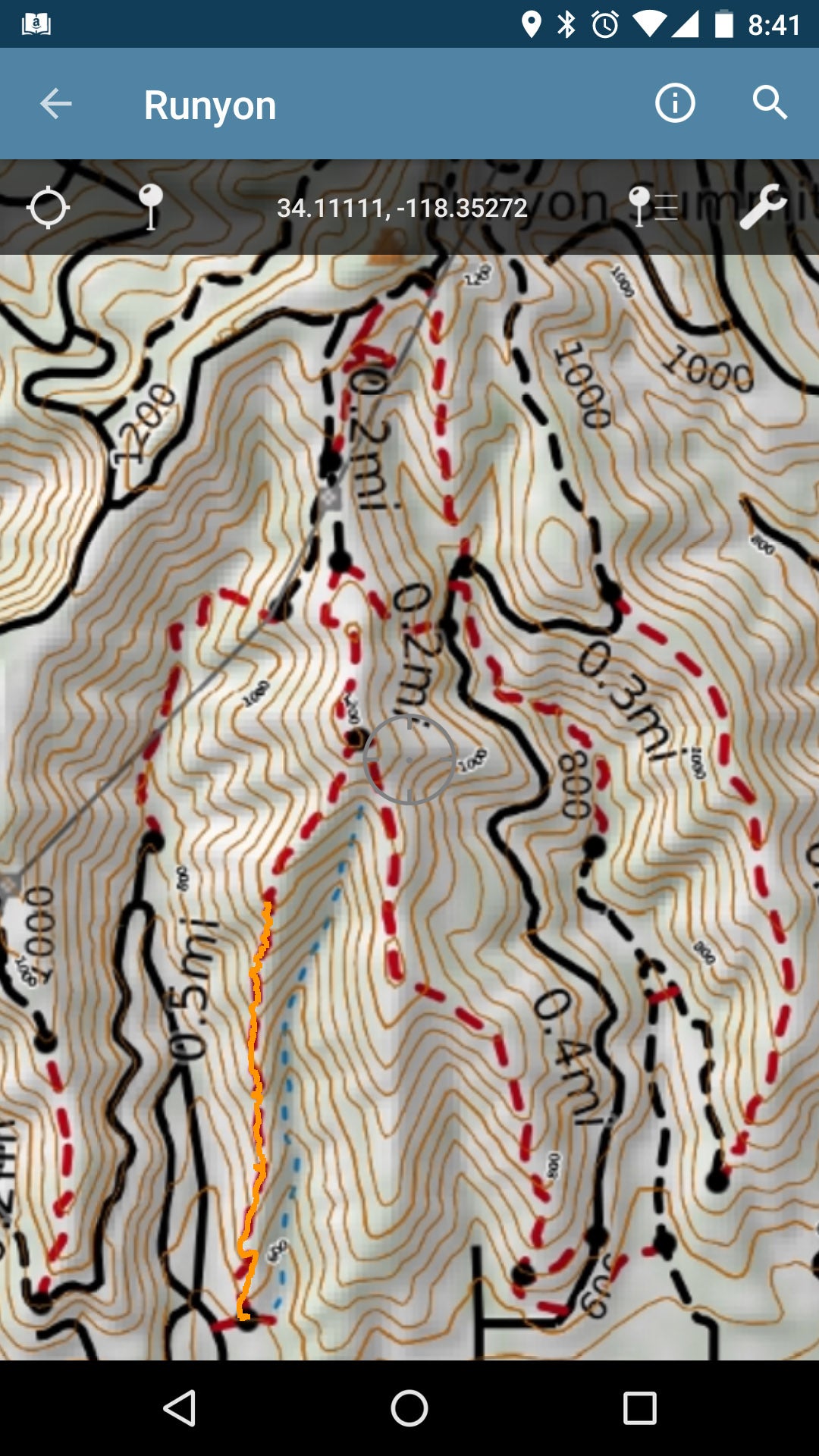

We’ve previously explained how to export most of CalTopo’s layering functionality to your smartphone using powerful navigation apps like (iOS) or (Android). Those apps are great, if you’re prepared to put in the time to learn how to use them, but they share CalTopo’s frustrating user experience.

Lately, I’ve been taking the far simpler approach of building my maps in CalTopo, then exporting them as PDFs (all of CalTopo’s PDFs contain geospatial data). You can—and should—print these out as a non-battery-based, unbreakable backup. But importing them into a simple navigation app like (iOS and Android) gives you a dead simple user experience, combined with vastly powerful and in-depth maps. The result is as simple to use as Google Maps—just open up the Avenza, and a blue dot shows you your location. Just here instead of yellow streets, it’s contour lines, trail locations, slope shading, satellite imagery, and whatever else you want, all working whether or not you have cell signal. That this much navigation information can be accessed so easily is unprecedented. That it’s totally free is freaking awesome.

Jacobs earns money by selling subscriptions for CalTopo to organizations and power users. As described above, those PDF maps are only 8.5-by-11 inches (the dimensions of standard sheet of A4 paper). To save a larger map with more detail, a larger area, or both, you’ll need to subscribe (starting at $20/year). Considering a single paper trail map like created by Tom Harrison are each about $10, that’s good value. Invest a half hour of work, and you’ll be able to create your own, custom maps that are much better than even Harrison’s efforts.

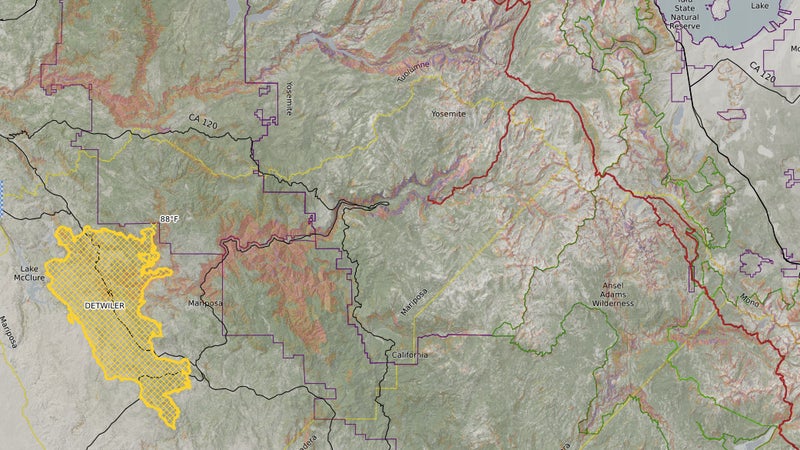

There are, of course, other programs and apps that will allow you to combine various layers of topo, satellite and other data. I use , for example, to show me specific game management units, and hunting zones, paired with land management agency information. But while that specific functionality may not be matched by CalTopo, nothing else offers the ability to compare multiple sources of topo data, with powerful data points like historic fire areas, and even currently active fire boundaries, or the aforementioned slope shading. Heck, you can even input your own, custom geospatial data.

I asked Jacobs to describe what he thinks makes CalTopo unique. “It’s the ability to take a single plot of the earth and look at it 10 different ways using the combination of different map layers, and the ability to collaboratively work on that with someone else remotely,” he says. CalTopo allows you to collaborate on map building in much the same way Google Docs allows you to work on documents or spreadsheets.

How is this enabling people to navigate in entirely new ways? “One example is a user who was recovering from an injury but still trying to climb peaks,” says Jacobs. “Since this involved a lot of talus fields, she would carefully trace her route using satellite imagery in CalTopo, and cross-reference by bringing the track into Google Earth, in order to find the cleanest line that minimized the risk of re-injury. She then loaded the route into her GPS and followed it very carefully.”

A long time ago, I used be reliant on major routes, trails, or destinations to plan my outdoor activities. If it wasn’t illustrated on a map I bought, I didn’t (or couldn’t) visit. Now, thanks to this awkward-to-use, low-budget website, I’m able to not only head into the wilderness armed with vastly more powerful data, but also, by searching forums for waypoints, getting them from friends, or recording them myself, I’m able to leave the beaten path behind. I am free to find and experience much more diverse areas, and enjoy the outdoors much more as a result.

This, or something like it, is going to be what enables you, your friends, and probably even people we don’t like to go farther outdoors, and do so in new ways, new areas, and hopefully with more information that empowers them to make better, safer decisions. Will 21st century mapping tools change the backcountry as much as they’ve changed our cities and suburbs? Undoubtedly. But it’s still too early to say what that will look like.

Backcountry navigation no longer looks like it used to. Hopefully that’s a good thing.