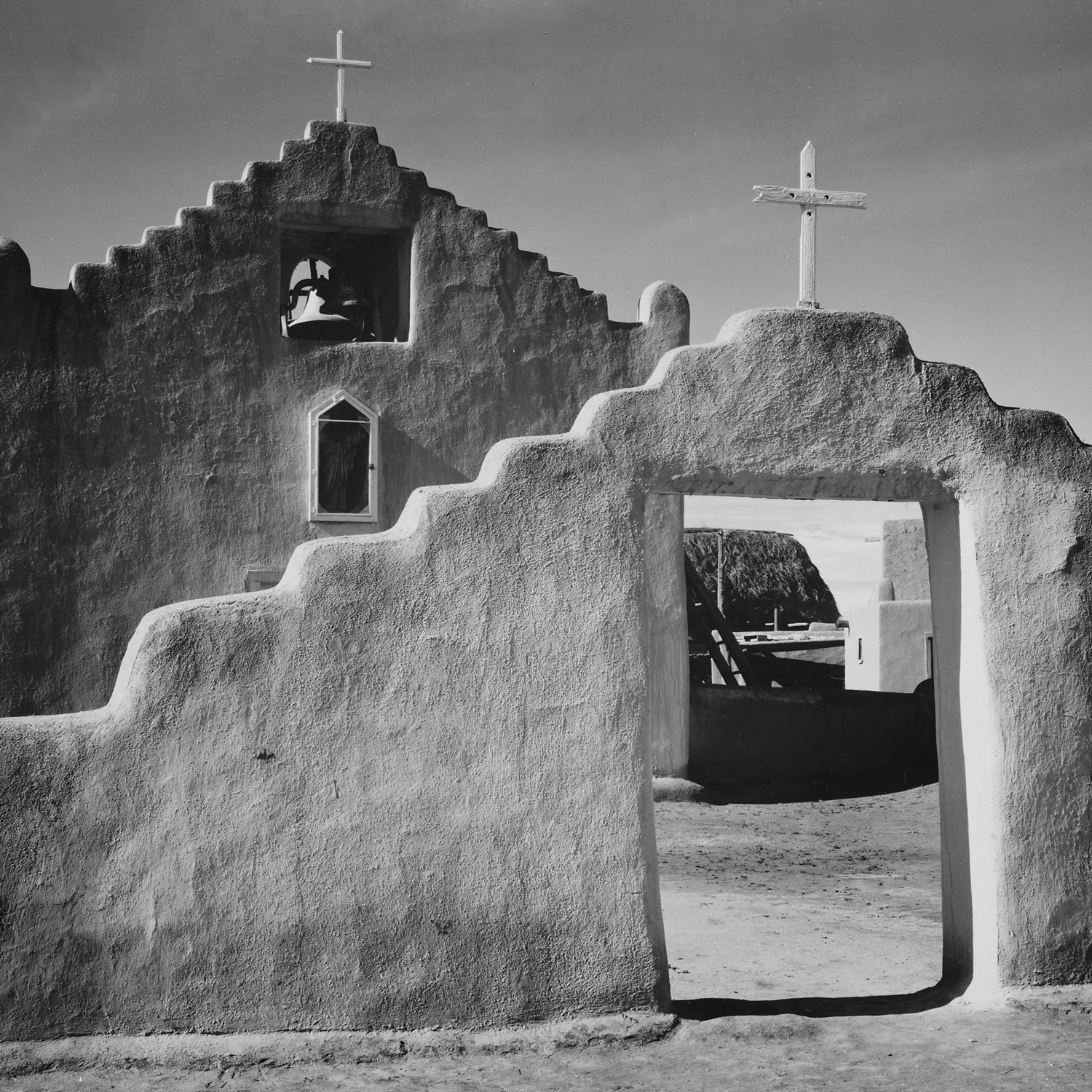

A few months ago our family had the most amazing experience. It was Christmas day at . Thick storm clouds hung over Taos Mountain, snow pelted our faces, and three inches of freshly fallen powder squeaked beneath our boots as we joined several hundred other visitors to watch the pueblo’s traditional Christmas Day Deer Dance. The sign at the entrance was non-negotiable: NO PHOTOGRAPHS OR CAMERAS OF ANY KIND. So we left our phones in the car.

For more than an hour we watched the sacred dance. It’s not a performance; it’s a ceremony. First the women danced, in beautiful bright dresses and bare arms. Then the men appeared, walking silently in two lines from the pueblo buildings. They wore fresh deer hides and little else; others wore mountain lion skins or fox pelts or raven feathers. Some were dressed as hunters, with arrows in their belt. They danced in a tight circle for a long time; they did not appear cold, and they took no notice of us. Occasionally, one of the hunter dancers would catch one of the deer dancers and sling him over his back and make a break for an opening in the circle, whooping as he did. One of the elders had built a fire and we stood around it at a respectful distance, warming our hands.

Except for the clothing worn by visitors, there was nothing to suggest it was 2016. It could have been 1925 or 1825. The women’s dresses and the men’s costumes, too, would have changed little over the centuries. Smoke crept into the sky from chimneys in the . The most notable absence, of course, was smartphones. Nobody was holding them up in front of their faces, arms outstretched above their heads, jockeying for a better position in the crowd. We weren’t watching the dance through our devices, we were witnessing it with our whole selves.

We’re so busy focusing on getting the right image that we miss the moment.

In the 22 years I’ve lived in New Mexico, it was easily the most remarkable thing I’ve ever experienced. I became aware, with a sense of growing alarm, that I wanted to remember everything, but I didn’t have a camera. I would have to remember the smell of the burning juniper boughs and the feel of the frigid wind strafing my face, and the women’s white leather moccasins and elaborately beaded dresses and the awestruck expression on my young daughters’ faces.

We live in an age of hyper-documentation. Resource Magazine estimates that more than ; the average American snaps three per pictures day. That doesn’t sound like much until you do the math: 1,000 per person per year, not including special occasions when you take dozens of rapid-fire outtakes of the same scene.

Psychologists have raised the concern that of themselves. Then there’s the question of memory: Do photographs enhance our memory of certain events or impair it? A 2013 study by psychologist Linda Henkel, published in Psychological Science, followed participants through a museum and found that those who took pictures recalled fewer objects on display and fewer details about those objects; . We’re so busy focusing on getting the right image that we miss the moment.

Photographs also create a mental and technological backlog: they clog our hard drives, our cloud storage, our phones, even our minds. When my eight-year-old daughter saw how frazzled I was by the sheer volume of data in my life—much of it my own creation—she said, “Mama, you need to delete some things from your brain.” My phone is so jammed with photos and data it no longer rings, and I haven’t been able to take a picture in weeks. Even when I delete hundreds at a time, I still have no room.

On one hand, it’s a drag to leave the camera tucked away. I miss taking pictures of my daughters moving through their days, the little loveliness I might otherwise forget, like the two of them reading side by side at our neighborhood bookshop, heads bent over a page. Or my six-year-old repeatedly leaping into the air on the walk to school today, trying to touch a tree branch just out of reach, would have made good video, and I would have liked to photograph the pretty tulips and lilac bushes lining the street. And yet, like that magical day at Taos Pueblo, it’s also strangely liberating. I’m not walking through my days looking for ways to capture them for the future; I feel less like a consumer of my life, and more like the one living in it right now, moment by moment. Maybe the universe is trying to send me a message. . These are the details you will never forget.

I feel less like a consumer of my life, and more like the one living in it right now, moment by moment.

The solution to our photo deluge isn’t black and white. Henkel, the study’s author, concedes that . The key is to be conscious of how, when, and why we’re taking photographs—to preserve a moment, to capture a feeling, or to publish on social media? And, once in a while, as I learned at Taos Pueblo, it’s helpful to leave your camera or phone behind and be fully present in the moment. Afterwards, encourage your children to find other ways to preserve the memory, by writing stories or poems or drawing pictures.

Finally, make an effort to edit and . Make a photo book or picture album or frame favorite images for your wall. Pictures can’t reinforce or shape our memories, and our family’s personal stories, if they’re stored in files we rarely open. We need to be able to see them.

My father was a photographer and picture editor at National Geographic for nearly 30 years. He spent his whole career taking pictures and then his whole retirement editing and archiving them. When he was diagnosed with terminal cancer in 2010, his project took on a new urgency and became a race to the end. Seven years later, his professional collection seems almost quaint compared to the , but the task plagued him until the very end. And yet I’m so glad he finished. I keep his pictures on an indestructible hard drive under my desk, and looking at them from time to time is like having a little visit with Dad—and my childhood. Someday I’ll get around to having some printed in black-and-white for my walls. Just as soon as I delete some other stuff from my brain.