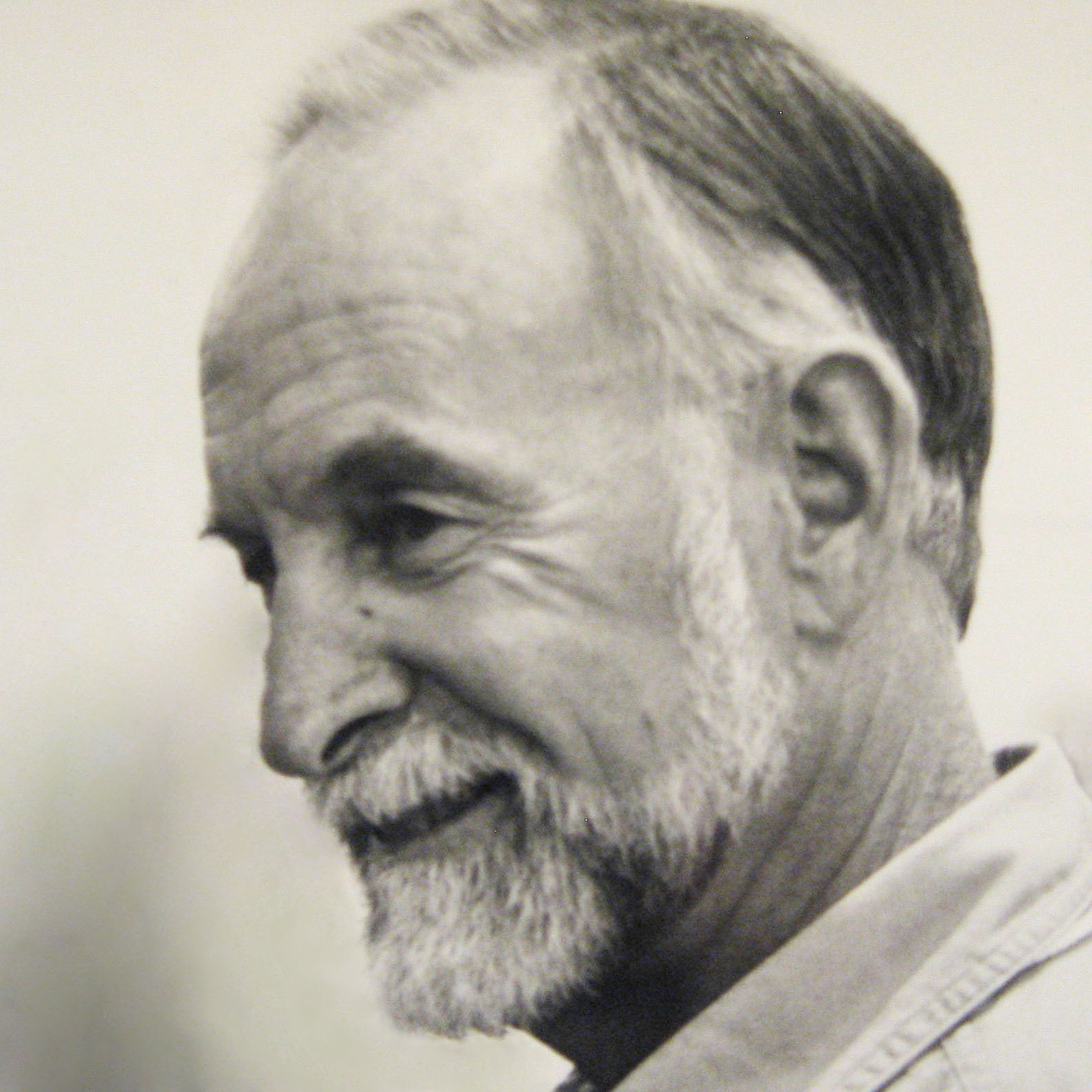

Rock climbing is a game of rules. It has no meaning without arbitrary limits on the use of gear—drilling bolts, not drilling bolts, hanging ropes from above—and shared agreement about what constitutes a great achievement. Nobody in the history of North American rock climbing did more to define those rules, and the culture of climbing today, than Royal Robbins, who died Tuesday, March 14, at the age of 82. Put another way, every man and woman who currently climbs outdoors, regardless of whether or not they’ve heard of the guy, lives in a world that Royal Robbins created.

Robbins was born in 1935 and grew up working-class poor in trailer parks around Southern California. He learned to climb in the early 1950s at a granite crag called Tahquitz, outside Los Angeles, and immediately established a pattern of audacious bravery. First, at the age of 17, Robbins tackled the then-infamous Open Book, the first multipitch 5.9-rated climb in the United States, which had been climbed for the first time only one year before with the use of so-called direct aid, meaning those original climbers hammered gear into the cliff—2×4 lumber, as it happened—then attached stirrups to that lumber and stepped into the stirrups to make upward progress.

“So Royal goes up there with a white yachting rope and cheap-ass tennis shoes and leads the whole thing free, meaning he’s got a rope tied around his waist, but he’s pulling on the rock to make upward progress, not on gear,” says John Long, a leading Yosemite climber of the generation after Robbins. “And he’s got no protection except the few chunks of wood that the older guys left behind—no way that stuff was going to hold a fall—so Robbins basically free-solos the first multipitch 5.9 in the United States. People today have no way of appreciating how extreme that is.”

Robbins did the same thing in Yosemite for the second ascent of the great Steck-Salathé route, the most significant rock climb in North America at the time, on Sentinel Rock. Instead of the five-and-a-half days taken by Allen Steck and John Salathé, Robbins took two days. “If you were to give today’s gym-climbing national champion the garbage pitons Robbins was using, a hammer, and a cheap rope and tennies, and tell them to go have a crack at that, I guarantee they’d come back with horror stories,” says Long, who knew Robbins well.

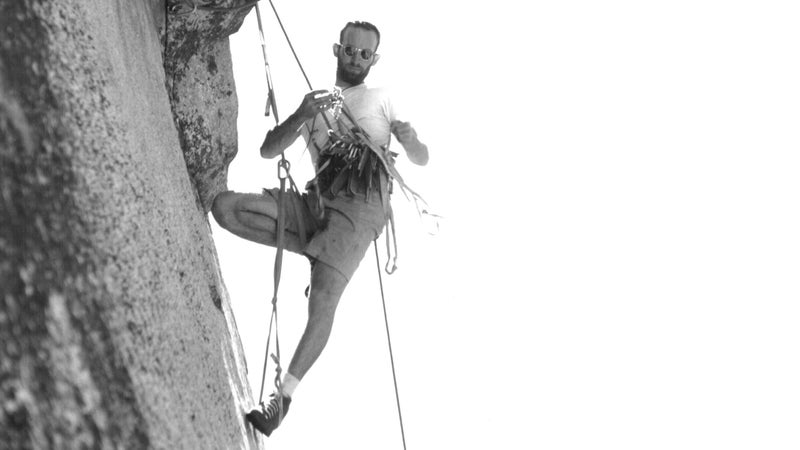

Robbins soon became a regular at Camp Four, the Yosemite rock climbers’ campground, and his climbing career over the next 20 years reads like a litany of all the most important ascents of the so-called golden age of climbing. He did the first ascent of the Northwest Face of Half Dome in 1956 and watched in horror as Warren Harding did the first ascent of El Capitan, spending 18 months laying siege to the wall with fixed ropes and 125 metal bolts drilled into the cliff. Harding finally finished the job with a 47-day push in 1958, after which Robbins did the second ascent in just seven days. It was an ascent so impressive, and so glaring in its contrast to Harding’s, that it served as a manifesto for the future of Yosemite rock climbing—declaring, in essence, that boldness and commitment and speed would forever count for more than engineering and logistics.

Robbins turned that manifesto into a masterpiece of his own three years later, when he, Chuck Pratt, and Tom Frost established the second-ever route on El Capitan, the Salathé Wall, arguably the greatest pure rock climb on earth, then and now. “It was perfectly clear to us that given sufficient time, fixed ropes, bolts, and determination,” , “any section of any rock wall could be climbed.” To remove this element of certainty, “which tends to diminish our joy in climbing,” as he put it, Robbins and his teammates dropped their fixed ropes after day three, and then, on a rock face vastly more intimidating than anything ever attempted in that fashion, spent six more days pioneering a pathway up through an overhanging headwall toward the summit—with absolutely zero hope of locating a single extra cup of water, much less of rescue. “It is just so wildly steep up there,” says Alex Honnold, “To be nailing pitons in there, for the second-ever route on El Cap…I mean, they were basically questing up a virgin wall.”

“I think he was aware that he was bigger than life, and he knew that he had a responsibility to share that with people.”

The competition between Robbins and Harding turned bitter for a while in the late 1960s, when Harding established the Dawn Wall route by drilling many hundreds of permanent metal bolts into the cliff. Robbins—like a self-appointed minister of righteousness—promptly repeated Harding’s Dawn Wall route with a hammer and cold chisel, chopping Harding’s bolts along the way as if to erase an abomination in the eyes of the mountain gods. That episode has gone down in climbing history as an ugly one, but it represents the essence of Robbins’s contribution to climbing today—an insistence that rules and ethics matter. In practical terms, that means always using whatever gear will cause the least possible damage to the rock. It means respecting the first ascent of a given climb as a work of art, such that later climbers never change the essential nature of the route by, say, adding new permanent safety hardware. Lastly, it means celebrating the constant push toward bolder and braver ways of climbing.

Robbins later became a world-class whitewater kayaker, joining The North Face founder Doug Tompkins and Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard on first descents of many of the great rivers of the Sierra Nevada. Reg Lake, who was part of that crew, recalls carrying their kayaks up to 8,000 feet on the eastern side of the Sierra, and then spending nearly a week running the headwaters of the San Joaquin—through Class V rapids in boats heavily loaded with camping gear. “Things got quiet out there,” Lake says. “That’s really when Royal’s insights and philosophies would come out—almost like Zen quotes. I think he was aware that he was bigger than life, and he knew that he had a responsibility to share that with people.”

For elite climbers like Long, however, the core of Robbins’ legacy is pure guts. “The guy was just always trying to up the boldness quotient,” Long says. “He brought raw courage and preternatural talent and drive, and there’s no way to match that experience now.”