For our 40th anniversary, we're featuring people who have changed our world by redefining risk and making human limits seem like just a failureĚý´Ç´ÚĚýimagination.Ěý

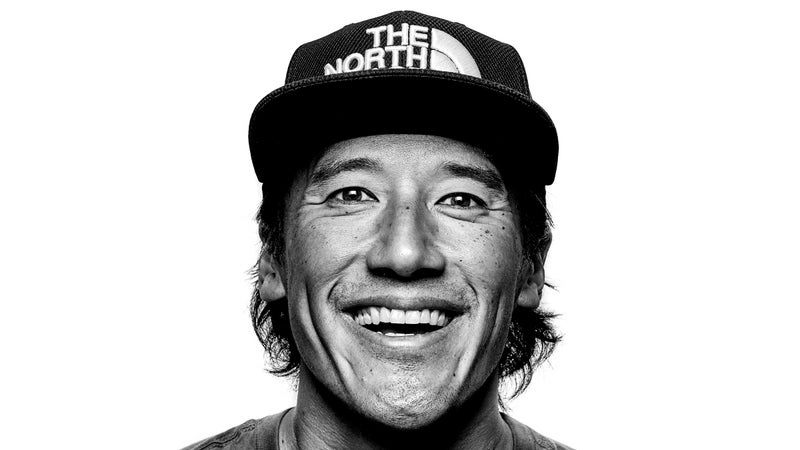

Jimmy Chin

You may not think of Jimmy Chin as the absolute greatest photographer, cinematographer, or even mountaineer who ever lived. But name one other guy who can do all three at his level. He’s shot a ±·˛ąłŮľ±´Ç˛Ô˛ą±ôĚýłŇ±đ´Ç˛µ°ů˛ą±čłóľ±ł¦Ěýcover, completed a first ascent of Mount Meru, and produced an award-winning documentary about that climb with codirector Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi, his wife.

His career began in 1999, when he grabbed fellow Yosemite big-wall rat Brady Robinson’s camera as he slept atop El Capitan and shot a picture of Robinson that was quickly featured in a gear catalog. Since then, I’ve written about both his successes (like skiing the Southeast Ridge route down Mount Everest with Kit DesLauriers in 2006) and his failures (like an attempt to document snowboarder Steven Koch’s abortive 2003 descent of a couloir on Everest). In that time, I’ve realized that there are three secrets that have helped him along the way. First, he doesn’t worry too much about what gear he’s using. When I was interviewing him back in 2004, he had a mid-grade Nikon. Though he’s since upgraded, he uses the same 24–70 f/2.8 lens for many of his shots, proof that it’s the archer and not the arrow.

Keeping it simple hasn’t held him back, and that’s because of his second secret: he anticipates where the world is going.ĚýChin launched production house  with his pals Renan Ozturk and Tim Kemple just as brands like the North Face realized that they needed content creators as much as professional hardmen. (Chin and Camp4 have since parted ways.) He was  soon after it launched, and his 1.5 million followers demonstrate that popular photographers don’t need magazines to find an audience.

Finally, he surrounds himself with people who raise his game—like Conrad Anker, media moguls Arthur Sulzberger Jr. and Vice’s Shane Smith, and, most important, VasarÂhelyi. In 2013, what he’d hoped would be his first feature documentary, House of Cards, about the 2011 Meru climb with Ozturk and Anker, was still in shambles. It was rejected by Sundance and could easily have been abandoned. But Vasarhelyi, who had already directed two successful documentaries, was convinced that there was an amazing film there. She hired New York editor Bob Eisenhardt, reshot most of the interviews, and łŮłÜ°ů˛Ô±đ»ĺĚýMeru into the highest-grossing indie doc of 2015.

Chin now lives with Vasarhelyi and their two children on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, where Chin has become mountaineering’s first pop-culture celebrity. In April,  the 400-foot spire atop One World Trade Center to shoot a Ěý´Ç´ÚĚýThe New York Times Magazine. It’s the kind of ascent most climbers who’ve visited New York City dream of. Of course, it was Chin who figured out how to make it happen. —Grayson Schaffer

Jeb Corliss

With a genius for heart-pounding spectacle in breathtaking locations, California daredevil , 40, has plumÂmeted from the Eiffel Tower, the Golden Gate Bridge, and Angel Falls in Venezuela. Last year he darted in his wingsuit through a target suspended above the Great Wall of China. Beyond the stunts, Corliss—with his all-black wardrobe, blunt sound bites, and attitude seemingly calculated to provoke (he stuck out his tongue at news photographers after he was arrested for attempting to parachute from the Empire State Building in 2006)—has forged an image as an action figure in the most dangerous sport ever devised.

Twenty years ago, when Corliss began jumping, BASE was clandestine. But he learned that he could make a name for himself by filming his jumps and selling the footage to TV producers. He set new standards for midair acrobatics, enrolling in diving classes with a coach at USC who taught him how to pull off backflips and twisting somersaults while plunging from buildings and cliffs. The result: Corliss pioneered professionalism in BASE.

When wingsuits came on the scene in the 2000s, coinciding with smaller POV cameras and YouTube, Corliss envisioned fresh possibilities. In 2011, buzzing just feet from a Swiss mountainside, he narrowly avoided colliding with a friend clutching a group of balloons as a prop. An online edit of the hair-raising footage, called “,” has been viewed more than 31 million times. Months later he flew through an arch in the side of a mountain in China as tens of millions of people watched the multimillion-dollar production on television.

Just as any high-adrenaline sport takes its toll, BASE jumping—Âparticularly with wingsuits—has seen mounting fatalities, including nearly 40 in 2016. A leading cause is the kind of close-call proximity flying, popularized by Corliss, that has killed many of the sport’s most accomplished practitioners. But Corliss remains undeterred. Crashes and broken bones have simply become part of his highlight reel.

In 2012, for example, while filming for HBO on Table Mountain in Cape Town, South Africa, Corliss clipped a ledge, nearly killing himself and breaking both ankles, his feet, and a leg. Asked by a reporter if he had a death wish, Corliss replied: “If you wanted to die doing the shit I do, you’d die right away.” His wish, he explained, is to live and pursue his abiding childhood dream of flying. Fear of death doesn’t stand in his way. —Matt Higgins

Kelly Slater

Never mind the surfing for the moment—just take in his physical presence. At 21, Kelly Slater looked as if he’d been cloned from a bead of Elvis Presley’s Jailhouse Rock sweat. Today, at 45, he can out-handsome Jason Statham. At 70, he will be three-quarters Paul Newman and (sun damage taking its bitter toll) one-quarter Iggy Pop.Ěý

We looked at Slater a lot in 2017, as he says it will be his . And as we looked, we pondered many Slater-related stats and metrics, ranging from the wondrous to the surreal, beginning with his 11 world titles spread across a 28-year run as a professional. Then there are his 55 World Tour wins, seven Pipeline Masters victories, and 19 Surfer Poll Awards. The list goes on. Break Slater’s career into two pieces, right around the year 2000, and he’d be both the first and second winningest surfer on the tour. Or try this. When ÂSlater made his pro debut in 1990, current world champ John John Florence was negative two years old. Florence today gets the kind of rave reviews Slater did in his unbeatable prime. Still, ÂSlater holds an eight to five advantage in head-to-head matches against his young rival. Last August, when the two met in a final, in coral-Âgrinding barrels at TeaÂhupoo, Tahiti, Slater did everything but take Florence over his knee for a fatherly spanking on the way to an easy win.

Meanwhile, with the and its machine-made, pool-spawned, endlessly replicable perfect surf, Slater has performed the wave rider’s equivalent of solving cold fusion while simultaneously driving the sport into its first existential crisis. The rarity of good waves, and the eternal chess game a surfer must play to be in the right place at the right time to catch them, has Âalways defined surfing, shaped it, given it character. The pursuit is 98 percent longing, 2 perÂcent fulfillment. To surf is to suffer. Thus, on December 18, 2015, when Slater dropped a surprise video debut of his freakishly perfect wave, located in the manure-scented flats of Lemoore, California, the surf world froze on its axis. Wave scarcity is over. Or it will be at some now visible point in the future.Ěý

. Watch it again. There’s Slater at daybreak, looking like a million bucks in a winter jacket and wool cap, breathing steam, standing at the foot of his pool, waiting to get a look at his machine operating at full strength. The wave comes, but we don’t see it. The camera stays tight on ÂSlater as his eyes go wide, his mouth breaks into a huge, shocked grin, and he lifts his arms, saying “Oh, my God!” It’s a joyous moment. And maybe a little chilling. Slater jumps up and down and starts laughing the laugh of a man who has changed his sport forever. —Matt Warshaw

Stephanie Gilmore

learned to surf on a boogie board near her hometown of Murwillumbah, Australia, when she was ten. Nine years later, in 2007, she won the world title during her first year on the World Championship Tour. The 29-year-old now has six titles (and is currently on the hunt for number seven), has already been inducted into the Surfers’ Hall of Fame, is on the advisory board of the , and shreds the guitar. It’s no wonder she goes by Happy Gilmore. We asked Kelly Slater, the only person we could find who has won more titles, to explain just what makes her so good.

Kelly Slater: I first saw Steph surf on the Gold Coast of Australia when she was still a teenager. Her style is beautiful, a perfect balance of masculine and feminine, power and speed. She doesn’t over-surf or use too much aggression. She’s one of my favorites to watch. She’s always surprising everyone in the water with what she busts out on a wave. In my opinion, she’s the best female surfer of all time by a good margin. She was one of the first people I invited to my wave pool in Lemoore, California, and she had the best first ride of anyone yet. It was really easy for her to adjust and figure out how to ride the wave. Ten of my friends were around that week, and we all just hung on the side of the lake and watched her do her thing.

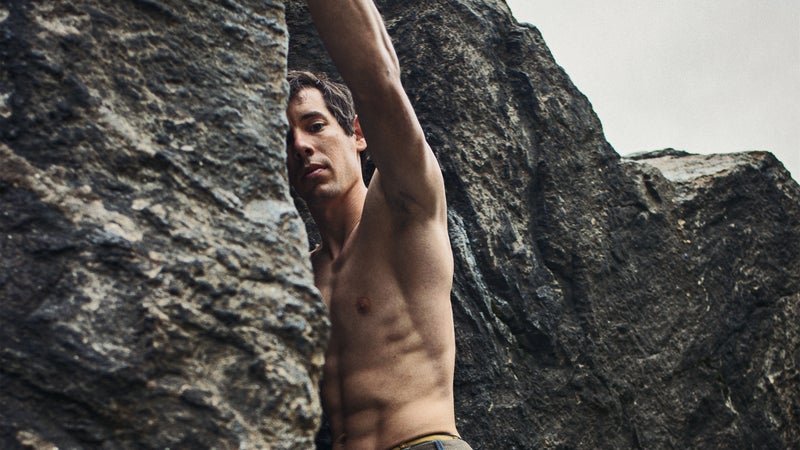

Alex Honnold

When Alex Honnold free-solos, climbing unroped, he has pretty limited options for retreat. He’s either got to climb up to the top or, maybe in a pinch, back down to the bottom or onto a ledge to await rescue. So far he hasn’t encountered any trouble he couldn’t get out of by himself.

For anybody who’s ever climbed, whether at a gym or on a local crag, the idea that you could go year after year, soloing routes as long as 2,500 feet and as difficult as 5.13, without ever falling would require magical thinking. Honnold’s continued solo-climbing practice has caused his friends to wonder whether his brain is wired differently, or whether he’s got a streak of pathological focus.

A few years ago, I accompanied Honnold, who is now 31, on a , where we discussed risk. His position on the topic is almost Vulcan: . Somehow his mind is capable of rationally separating danger from fear in situations that for the rest of us would induce panic, palm sweats, and sewing-machine leg.

During that speaking tour, the prospect of seeing Honnold packed auditoriums. He is part unassuming rock star and part circus oddity. Some of that reputation is thanks to a 2011 broadcast of 60 Minutes . (It also had climbers in hysterics over correspondent Lara Logan’s innuendo-laced fascination with Honnold’s large hands and whether or not they can fit in small cracks.) His household fame reached a new zenith in 2015, when he was the subject of a New Yorker cartoon.

But beyond the spectacle, Honnold offers a small grasp of how each of us might better manage our own fear: by breaking it into smaller components and dealing with them individually. Honnold has sometimes called the technique his “mental armor,” allowing him to function under acute stress. Famously, when he first free-soloed Yosemite’s Half Dome in 2008, his armor cracked and doubt flooded in. While filming the 2009 documentary , Honnold had a similar freakout while the cameras rolled. He stands there on Thank God Ledge, a twelve-inch-wide shelf 1,800 feet off the ground, with his back pressed to the wall and very calmly tells the camera, “Just a sec. I’m freaking out, actually.” To the observer, the meltdown is about as exciting as watching a computer reboot—he’s that much in control of his mind. Or as the South African tourist who happened to be standing atop Half Dome when Honnold pulled himself up over the edge said, “He’s stupid, but impressive nevertheless.”

Lately, Honnold has been spending more time climbing with a rope. In 2014, he teamed up with rock climber Tommy Caldwell to do the Fitz Traverse, a fantasy route in Patagonia that encompasses the entire Fitz Roy Massif. Their historic climb was chronicled in the short film A Line Across the Sky, which appeared on the 2015 Reel Rock Film Tour. Like the , it was hilarious, terrifying, and mind-blowing. —Grayson Schaffer

Marianne Vos

Imagine a woman on a bike in the rain, tearing up pancake-flat roads in a country without mountains. Dreaming of the Alps, she hammers into her only substitute: a nasty Dutch headwind. It’s cold and wet and bleak and gray, but this is her happy place. Because this is .Ěý

In Vos’s native Netherlands, . Vos was also born to stand on a podium. After earning her first rainbow stripes at 18—the prize for winning the Cyclocross World Championships—she systematically conquered nearly every major women’s race in the world. In 2012, at just 25, she was as the greatest female cyclist of all time and was named , edging out Sir Bradley Wiggins, that year’s Tour de France winner.

Now 30, Vos has , including two Olympic gold medals and 12 world championships across road, track, and cyclocross.Ěý

She is often referred to as the Cannibal, a comparison to Belgian rider , who dominated men’s cycling in the sixties and seventies. Coming in behind either athlete has long been regarded by much of the peloton as a win. “Second to Marianne isn’t too shabby,” said after taking the silver in the 2013 Cyclocross World Championships, a 94-second eternity behind Vos. “I can’t think of anyone as talented as she is, as motivated as she is. But it only makes everyone better.”

Once a self-described “shy schoolgirl,” Vos has turned the podium into a platform to elevate women’s cycling. In 2013, she joined a group of female pros in successfully petitioning for a women’s race at the Tour de France, called La Course. Launched in 2014, the 56-mile competition awarded $31,000 to the winner, the same amount the men’s winner receives. Of course, Vos won that, too.

In 2015, Vos for the first time in her life by overtraining syndrome. Never one to sit still, she used the break to found , an international club of female riders that aims to “bridge the gap between genders” by empowering women of all ages and abilities to spend more time on a bike. Cycling has always been about equality for Vos. When she was six, she watched her older brother race and saw no reason why she couldn’t compete. Her dad bought the smallest bike he could find, and Vos began her decades of domination. Many of her earliest wins required dropping all the boys.Ěý

Currently, Vos is looking to add to a list of career wins that tops 300. Where does one put so many awards? A Woolfian trophy room of one’s own? Actually, they’re crammed in a shed behind her house. She hardly ever looks at them. She’s too busy riding her bike. —Kim Cross

Laird Hamilton

Laird Hamilton’s life has played out like a tall tale. Raised by a single mother on Oahu’s North Shore, he was a toddler when he approached surf legend Bill Hamilton and asked him to be his dad. Bill obliged, marrying Laird’s mom shortly thereafter. Fast-forward 15 years, and young Laird, already six foot three and 210 pounds, is plucked from a similar stretch of beach by a modeling scout. Soon he’s perched on a motorcycle, with Brooke Shields on the back, in Life magazine.Ěý

After a modeling stint in Southern California, he moves back to the North Shore and quickly establishes himself as the alpha dog among a sea of alpha dogs. He’s fearless in giant surf and doesn’t mind jockeying for waves. He won’t enter contests on principle but is competitive to a fault. He takes up windsurfing and in no time is one of the best in the world. He stars in a hokey Hollywood surf flick called . He invents tow-in surfing—launching into heavy seas with the aid of a personal watercraft—and Âcatches some of the biggest waves ever ridden. He popularizes stand-up paddleboarding and paddles across the English Channel. He invents hydrofoil surfing, riding above the water on open ocean. He appears in as a James Bond stunt double.

Through it all, he’s had an uncanny ability to turn his lowest lows into his highest highs. In , a new biopic directed by Rory Kennedy, Hamilton describes a 2000 trip to Tahiti. He was on the brink of divorce from his wife, pro volleyball player Gabrielle Reece. And the surf world had mixed feelings about him—his ardent embrace of jet skis didn’t go over well with purists, who resented the motor assist.

So when a huge swell arrived at the shallow meat grinder of a spot called Teahupoo, bigger than anything ever surfed there before, Hamilton went out. His first wave was a terrifying 15-footer—small in height by big-wave standards, but pushed squarely into the world of the unrideable by the thickness of the lip, the shallowness of the reef, and the power of the open-ocean swell. He bottom-turned and pulled up into the barrel. In the moment, he thought of his soon-to-be-ex-wife, his life falling apart. He considered jumping off his board. But instead he held on, rocketing onto the safety of the shoulder. Pictures were soon on every surf-magazine cover in the world. Hamilton sat on the back of his jet ski and cried.Ěý

He went back to Hawaii with nothing left to prove and patched up his relationship with Reece. Now, at age 53, with arthritis in his hip and repeated Âankle breaks, he still hasn’t slowed down. He’s working on perfecting his foil-board technique with a single goal, the same one he’s had his entire life: to ride the biggest wave he can find, forever. —Matt Skenazy

Lindsey Vonn

Looking back, the first phase of Lindsey Vonn’s 26-year career seems pretty run-of-the-mill for a world-class athlete. As a teen in Vail, Colorado, she was a slalom prodigy. Then, in her early twenties, she was a downhill star on the World Cup circuit. There was some drama around the 2010 Vancouver Olympics—a crash while training—but she ended up winning gold there, too. In 2012, Vonn petitioned FIS, skiing’s governing body, to let her enter men’s races. Maybe she was making a point about gender relations, or maybe she was just bored.

The second phase of Vonn’s career—which is also the celebrity-dating, gala-attending phase—has revealed a more interesting side. She went public about her struggle with depression, then suffered a series of potentially career-ending crashes. Starting in 2013, in five separate wrecks, she broke her left ankle and both knees, tore her medial collateral and anterior cruciate ligaments, and fractured her right humerus. At least, those are the injuries we know about. Vonn also has a hisÂtory of racing with undisclosed ligament tears.Ěý

But here is what’s most amazing: during that injury-riddled period, Vonn, who is now 33, won 23 World Cup races. That’s only ten fewer than Bode Miller did in his entire career. She has worked and willed her way out of casts and knee braces, into the weight room, onto the ski hill, and back atop the podium. Again and again.Ěý

There was a time when it looked like Vonn’s rocky relationship with her dad, her divorce from Thomas Vonn, or her romance with Tiger Woods might distract from her brilliance. Today, with Vonn’s final Olympics around the corner and a ten-inch scar on her right arm still scalpel fresh, it’s hard to think of her as anything but the best American skier ever. She is technically pristine, fearless, and, in race after race—77 and counting—the fastest woman on the hill. —Peter Vigneron