Over the past decade, —from cashew to soy to coconut—has dairy farmers and legislators in bovine-rich states pissed. Last month, 36 members of Congress penned a letter to the FDA for anything but liquid coaxed from a cow’s udder. In the letter, the group claims that nut milks are an imitation and therefore must be labeled similarly to imitation cheese or nondairy creamer. “While consumers are entitled to choose imitation products, it is misleading and illegal for manufacturers of these items to profit from the ‘milk’ name,” Patrick Welch, (D-Vermont) .

The timing of this letter isn’t coincidental. Dairy prices have dropped 40 percent since 2014, , a fact Welch emphasizes in a recent news release. The price drop is mostly due to falling worldwide demand, especially in China, says Jerry Cessna, an agricultural economist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture. While nondairy products are certainly growing in popularity, possibly at the expense of traditional milk—Mintel, a market research firm, published a that found sales of dairy milk had dropped by 7 percent in 2015 while sales of nondairy products over the same period rose 9 percent—deeming soy and almond milk “illegal” is quite the accusation. We decided to look at what’s claiming to be milk, how nutritious it actually is for you, and whether it deserves to be labeled like dairy.

How Healthy Is Milk?

A growing population of Americans is concerned that dairy might not be the healthiest option. The scientific verdict on that, however, is still out. “Milk is complicated,” says David Katz, founding director of the . “Anyone who says it is all good or all bad is expressing an opinion.”

A scan of the scientific literature shows that milk has both beneficial and harmful properties. Katz says that, especially among kids, drinking milk seems to correlate to better health outcomes and lower weights, as documented in a and a . However, not all studies are in agreement. For example, a of previous studies found a mixed bag: eight reported lower rates of high BMI among regular milk drinkers, but seven reported no effect, and one found the opposite to be true. Other research shows that milk could be harmful— published in the European Journal of Nutrition found an association between high-fat dairy intake and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease mortality. Plus, “there’s also the company milk keeps,” says Katz, referring to the potentially worrisome antibiotics and hormones large-scale dairy production relies upon.

Milk does have nutritional benefits, of course. It contains protein and calcium and is usually fortified with vitamin D. The fat in milk can be satiating, which may keep us from eating crappy food alongside it. But it’s easy to get these same nutritional benefits from nondairy options, argues Katz. Soy milk contains good, usable protein, and most almond milks have added calcium. “There’s some evidence that the combo of lactose (found only in dairy products) and calcium are better for absorption, but it’s pretty minimal,” Katz says. And this one fact alone shouldn’t keep you married to dairy, he adds.

Is Milk Even Natural?

You hear this question bandied about among . But arguments for or against milk from an evolutionary perspective are fraught with inconsistencies. Sure, humans are the only mammal to enjoy the mammary bounty of another species; paleo proponents, in particular, . But Katz counters that certain sectors of the human population have clearly adapted to drinking milk.

“Natural selection is continuing to happen,” he says, adding that declaring drinking dairy as unnatural from an evolutionary perspective requires stopping the clock at a somewhat arbitrary point in time. For example, , humans in certain parts of the globe began drinking animal milk and slowly developed the necessary enzymes to digest it. Because milk is nutrient rich, those who could digest it had a clear biological advantage and thus produced more milk-digesting offspring than their counterparts who lacked the adaptation. Katz asks: why is what we ate 8,001 years ago natural and what we started eating 8,000 years ago unnatural?

But there’s a more logical argument against milk than the evolutionary one: milk production today comes with a pretty substantial environmental price tag. According to a in the International Dairy Journal, each gallon of milk creates 17.6 pounds of carbon dioxide, which accounts for everything from the fertilizer used to grow feed and hay to the plastics used in packaging to the gas used in shipping. The entire dairy industry is responsible for 2 percent of America’s annual emissions—. Plus, cows need large amounts of land and water, as do milk alternatives. A from the California Department of Agriculture found that while dairy milk is much more carbon intensive, almond milk production uses substantially more water than traditional milk—1,611.62 gallons of water versus 77, respectively, per one liter of milk—and requires a lot more fertilizer.

So What Is It?

In their letter to the FDA, the legislators mention that milk has “a clear standard of identity defined as ‘the lacteal secretion, practically free from colostrum, obtained by the complete milking of one or more healthy cows.’” What they’re referring to is the FDA’s Electronic Code of Federal Regulation’s definition of milk, which can be found . The legislators argue that because plant milks don’t match this definition, they must be labeled as imposters.

From a legal standpoint, they may be correct. According to the , “a new food that resembles a traditional food and is a substitute for the traditional food must be labeled as an imitation if the new food contains less protein or a lesser amount of any essential vitamin or mineral.” While almond milk can be fortified with calcium and vitamin D, most brands don’t match the protein content of milk.

But what’s less clear is whether limiting “milk” to products extracted from a living thing would mean any living thing’s juice might qualify. Like, say, . We emailed Representative Welch and asked for his take. He didn’t respond.

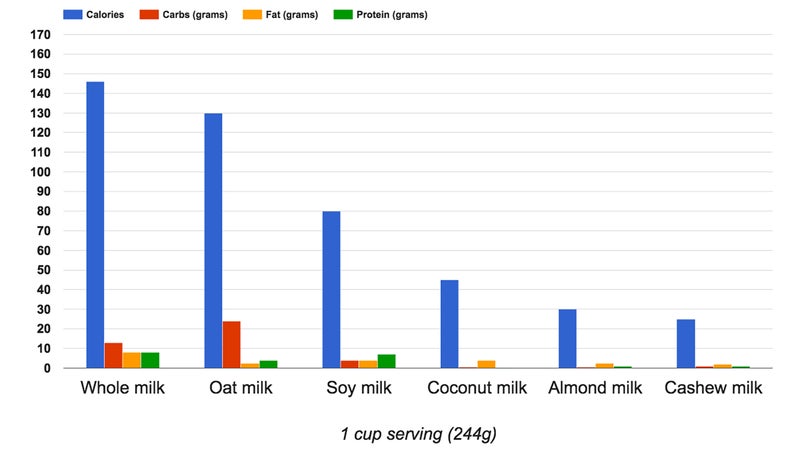

Finally, it’s worth asking: are American consumers truly confused about where plant milks come from? Sure, we can understand Americans scratching their heads at conflicting health research or the evolutionary arguments for or against the beverage, but it seems unlikely that anyone thinks soy milk comes from the breasts of soy beasts. However, Pierre Chandon, a marketing professor specializing in food labeling at , an international business school, thinks it’s less about Americans being confused about where these products come from and more about them equating these products as nutritionally similar. Milk is full of protein and calcium and, in moderation, is completely fine—if not good for you. Neither almond nor soy milk can match the protein of dairy. Many fortified versions of alternative milks get closer, especially in calcium and vitamin D, but they are still not as nutrient rich, ounce per ounce, as good ol’ whole milk.

“The goal of these regulations is to protect real milk,” Chandon says. “If you don’t draw a line and say that milk is only for dairy products, then you wouldn’t be able to forbid future usage, like, I don’t know, ‘vodka milk.’” And while he doesn’t think changes in labeling will alter the buying habits of almond milk devotees, Chandon adds that there are precedents of labeling changes that triggered big market shifts. “A good example is feta cheese, which is made from sheep’s milk only in Greece. However, a lot of the feta cheese sold outside Greece was made from cow milk. After a long judicial fight, Danish producers were banned from using the name feta, and exports of real Greek feta cheese increased by 73 percent in one year.”

The takeaway? While dairy milk gives you the biggest bang for your buck, the term “milk” does an industry good, and banning its use from nondairy products could severely impact plant-based products.