These Images May Be the Last Chance to Save Our Reefs

'Chasing Coral,' a new film premiering at Sundance, chronicles the desperate adventure of documenting the most imperiled ecosystems on earth

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

Over the past two years,��the worst thing that has ever happened to the oceans on humans’��10,000-year watch��has been unfolding in the tropics—and if not for one fanatical diver and his outrageous project, we would have mostly missed it.

I first clued in on November 2, 2015, when the New York Times ran a story titled “” that featured a jaw-dropping photo of a coral reef viewed from the waterline. In intense colors and depth of field, it showed a tree-topped cliff island in American Samoa surrounded by bleached elkhorn coral in all directions. I’d never seen a photo that captured so much reef in one hypersharp image��or that kicked you in the gut with so much bleaching, and it was all the more moving for the accompanying article, which explained that climate change and an El Niño weather cycle had combined to bring mind-boggling warmth to the Pacific, which had triggered the worst mass-bleaching event in history.

Corals are tiny, anemone-like, reef-building animals that derive much of their nourishment and color from symbiotic algae that live on their surfaces. But when temperatures rise too high, the algae turn toxic, and the corals must eject them to survive. Without the algae, the corals bleach bone-white and begin to starve. If water temperatures soon return to normal, the corals can recruit new algae and recover, but if not, they die within months. It takes water temperatures only one degree Celsius��above the average monthly maximum to trigger bleaching. Four weeks of that and serious bleaching sets in. Eight weeks (or fewer in even warmer water) and mortality begins.

The credit on the Times photo said XL Catlin Seaview Survey. I didn’t think much about it until a new Times story in April 2016��: a��sea turtle swimming forlornly over a vast bone field of bleached staghorn, nothing living in sight. Credit: XL Catlin Seaview Survey.

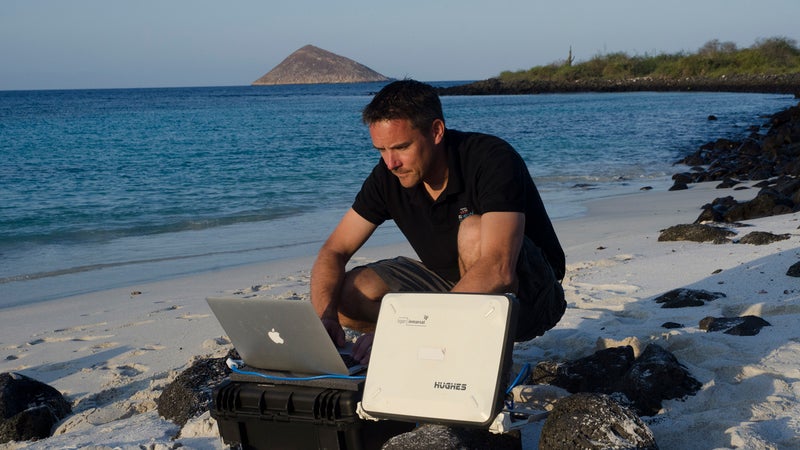

The environmental news site Grist featuring sickening photos of dead coral covered in brown ooze on the Great Barrier Reef. Another site displayed a shot of a diver photographing dead coral with some crazy-looking camera in Kaneohe Bay, Hawaii. Then the same diver shooting a killing field off Lizard Island on the Great Barrier Reef, and in New Caledonia, Florida, Indonesia, and the Maldives. Every time, the shots were breathtaking and deeply disturbing, and every time, the credit said XL Catlin Seaview Survey.

What on earth is the XL Catlin Seaview Survey? We all get to find out��on��January 21, because��it’s the subject of��, a new film by Jeff Orlowski, of��Chasing Ice��fame, that’s��premiering at the Sundance Film Festival. The film charts the survey’s efforts to document the world’s reefs in a series of unprecedented words, maps, photos, and eye-popping 360-degree virtual dives.

The diver in all those shots is Richard Vevers,��founder of the survey. Vevers is a tough guy to get ahold of, but I tracked him down in Australia as he was returning from two weeks diving and filming at Raja Ampat, Indonesia, one of the world’s last pristine reefs. “It was a reward to myself,” he said, almost apologetically. “For the last year and a half, I’ve been chasing around the world looking at dead things, and I needed to see something living. It was quite refreshing to see what we’re actually doing this for.”

Vevers had an unlikely transformation from Don Draper to Jacques Cousteau. After ten years as an ad man in London, he burned out, traveled the world, wound up in Australia, and trained himself to be one of the world’s top underwater photographers. Through his work, he became aware that coral reefs were the most imperiled ecosystems on earth, which is extremely bad news, because they are one of the most important. They support more than a million species—one quarter of everything in the ocean—on less than 0.1 percent��of the earth’s territory. When they go, so do those species, as well as the 500 million people who depend on reefs for their livelihoods.

Unfortunately, reefs get very little attention. “A lot of the issues were basically advertising issues,”��Vevers said. “Because what happens underwater is out of sight and out of mind. So I thought, let’s get together my old advertising friends and set up a nonprofit with the mission of revealing the oceans.”

They had no way of knowing that they were taking the final shots of a world no one will ever see again.

The Ocean Agency was born in 2010. Vevers designed a with three extreme wide-angle lenses that could take high-resolution 360-degree images. At a barbecue in Sydney, he met a representative from XL Catlin, a reinsurance company, which offered to fund the entire project on the condition that it be a scientific survey. So Vevers approached Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, the University of Queensland’s leading coral reef scientist, whose eyes lit up. There was no comprehensive survey of coral reefs, just small-scale local surveys that all used different methodologies. Hoegh-Guldberg told Vevers that the XL Catlin Survey could revolutionize the monitoring of coral reefs.

In 2012, they tackled the Great Barrier Reef, using a protocol developed by Hoegh-Guldberg. They photographed 150 kilometers of reef, taking a 360-degree image every two meters. Soon they had 105,000 images of the Great Barrier Reef, all GPS- and directionally located so the same photos could be taken in the future. They developed image-recognition software that could identify the species in each photo as accurately as a marine biologist, but 50 times faster. They made the entire database freely available online. And then they expanded their project to reefs worldwide.

This was no snorkel-tour joyride. Many of the world’s inshore reefs have already been hammered by boaters and pollution, so the Catlin team focused on remote, outer reefs, and that meant two-week trips on a live-aboard boat, often in heavy seas. The five-person diving team would wake at 5:30 a.m., prep their cameras, pack a lunch, and head out on small tenders for the day. At each site, two divers would enter the water while two other scientists wrestled the 150-pound camera and a second support scooter into the water.

They were rarely alone. At these remote sites, the marine life had rarely seen a human, and it was engrossed. “As soon as you jump in the water, the sharks just fly at you,” Vevers told me with a chuckle. “Big silver-tip sharks, over two meters, and they turn just at the last minute. You can actually hear the divers underwater squealing.”

The work was treacherous. Divers could be caught in underwater waterfalls, as massive amounts of water poured off a reef with the tide, or in currents that sucked them into the reefs. They always trailed surface buoys that could be tracked by the tender. They would do three dives, each 45 minutes long, returning to the main boat late in the day. “That’s when the work really begins,”��said Vevers. There was data to be downloaded, discs to be cleared, batteries to be charged. They’d collapse in their bunks and do it all over again.��They had no way of knowing that they were taking the final shots of a world no one will ever see again.

In 2013, on a long flight, Vevers watched Jeff Orlowski’s film Chasing Ice, which chronicles the photographer James Balog’s efforts to capture receding glaciers. “I called Jeff as soon as we landed,” Vevers said. “I felt like we had very similar projects. Coral reefs seemed like such a logical follow-up. We met a couple of times, and then Jeff decided to do a film.”

At the time, it wasn’t certain that Chasing Coral would include any images of mass bleaching, something Vevers himself had rarely seen.

“I jumped in the water, and I was absolutely shocked by what I saw. The hard corals looked like they’d been dead for years. It looked desolate.”

Then, in 2014, his life changed forever. The Catlin team was in American Samoa with Orlowski’s film crew to revisit a reef they’d shot a few months earlier. It had been extremely healthy, but there were rumors that it was starting to bleach, so Vevers returned to check it out. “I jumped in the water, and everything was bright white as far as the eye could see. That’s when it dawned on me how quickly this happens and how potentially devastating it could be for coral reefs globally.”��The American Samoa reef was known to be resilient. It had bleached during previous mass-bleaching events, then quickly bounced back as temperatures cooled. So a few months later, Vevers again returned to document the recovery. “It was completely dead,” he recalled. “This time, it didn’t bounce back.” The Catlin team released some shocking images to the media, and for the first time, the term mass-bleaching entered the public discourse.

“We realized we were the only team documenting this event globally, and we’d been there from the start, and we were in a unique position to tell the story.”��And the Chasing Coral team was with them all the way, shooting hundreds of hours of footage.

Working with Mark Eakin, the Coordinator of NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch program, , the XL Catlin team transformed into a rapid-response squad. Within days of getting an alert from Eakin, they’d grab their cameras and hop on a plane. They shot in Hawaii, Fiji, Taiwan, Maldives, Okinawa, New Caledonia, and the Great Barrier Reef.

Never before had the world seen what massive bleaching really looked like. “Because we’ve got the 360-degree cameras, it allows us to take the shots that really show the scale,” Vevers explains. “Generally it’s been hard to get news coverage of bleaching because there hasn’t been good imagery to back up the story.”

It was at Lizard Island, on the far north of the Great Barrier Reef, that Vevers received his worst shock. “It’s a beautiful island,”��Vevers said, “a real hub for science with a great coral cove, and it had a beautiful, healthy reef. It was my favorite spot in the world.”��The team had already photographed Lizard Island at the height of the bleaching, but Vevers returned with a second expedition four weeks later. “I jumped in the water, and I was absolutely shocked by what I saw. The hard corals looked like they’d been dead for years. . The soft corals were hanging down, and they were rotting. Just falling apart and literally dripping off the reef. It was shocking enough to see that transformation from healthy to dead in such a short time, but then when I got out of the water, I realized that I absolutely stank of rotting animals. I’d never heard of that, and I wasn’t expecting it. Often you look at a reef and it’s like looking at a garden, and it’s hard to appreciate that these are all animals. So when you smell it, that’s when the scale of the tragedy really hits home.”

For those of us who can’t smell it, numbers should suffice. . Some previously pristine reefs in the South Pacific lost almost everything. So far, about 20 percent of the world’s reefs have died during this bleaching event. And it isn’t over yet. The oceans are so hot, they no longer need an El Niño to kill coral. “The models indicate that we will see the return of bleaching in the South Pacific soon,”��NOAA’s Mark Eakin told me, “along with a possibility of bleaching in both the eastern and western parts of the Indian Ocean.”��NOAA forecasts a 90-percent chance of serious bleaching across that region by March.

Our only chance��is to reduce emissions to zero and then to start removing heat-trapping gases from the atmosphere. On the off chance that happens fast enough, 90 percent of the world’s reefs will still die, but there will be that other 10 percent.

“CO2 levels are already higher than corals can tolerate,”��Eakin confirmed to me. Our only chance, he explained, is to reduce emissions to zero and then to start removing heat-trapping gases from the atmosphere. “That process needs to start very soon and be very fast,”��he said. “Unfortunately, all indications are that it will happen much slower than needed.”

On the off chance that happens fast enough, 90 percent of the world’s reefs will still die, but there will be that other 10 percent. Maybe they’re in deeper spots that will remain just cool enough, or maybe they have corals that adapt particularly well. With his documentation of the mass bleaching nearly complete, Vevers is embarking on a new mission to survey—and save—those last refuges. With time, and a stable planet, they could repopulate the world’s oceans.

It sounds like a long shot, but Vevers likes to cite another long shot. In 1966, the humpback whale population was down to 5,000 individuals, just 4 percent of their original numbers. Most observers were getting ready to write their obituary. But then we stopped killing them, and they recovered better than anyone predicted. “I was expecting humpback whale numbers to be up 20 or 30 percent,”��Vevers wrote on his blog. “However, their recovery has been far more impressive than I expected. There are now around 80,000 individuals (65 percent of their original numbers) and their numbers are still improving at about 8 percent per year. That’s phenomenal recovery. There is no reason to think an ecosystem, like coral reefs, can’t bounce back in the same way.”

That’s an inspiring vision, but it only comes true, as Mark Eakin implies, if we bite the bullet right now. That means stopping emissions and beginning to sequester carbon now. It means taking a pass on that hamburger and munching a mushroom patty today. And stepping away from your car, hopping on your bike, and pedaling your ass off. Today.��