Shinya Tabei liked to tease his mother when she filled out forms. “Why housewife?” he asked. “For your profession, put mountaineer!” “But I am a housewife,” she insisted. “I just climb mountains because I love it.” Self-effacing to a fault, Junko Tabei, the first woman to summit Everest, succumbed to cancer on October 20. She was 77.

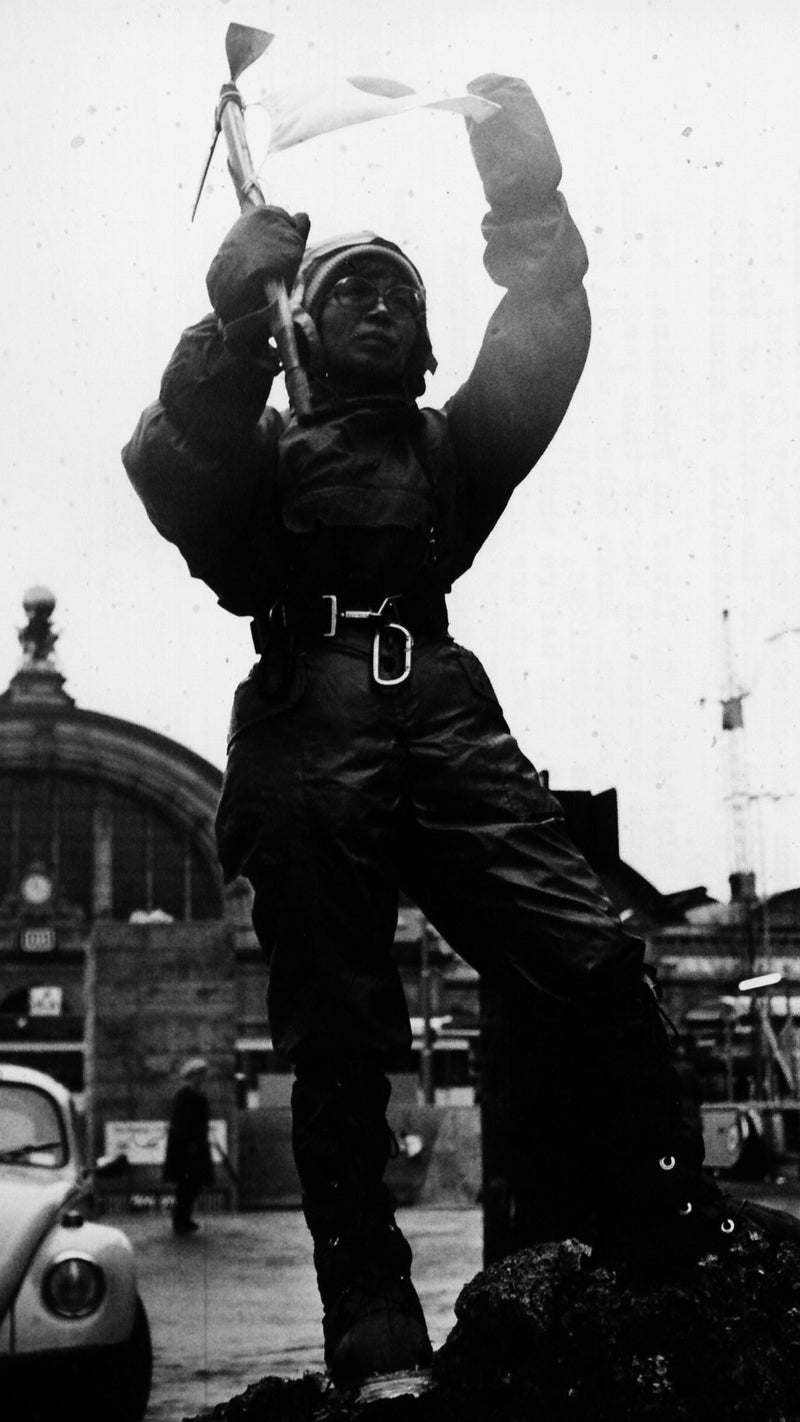

Unlike her personality, there was nothing modest about the expedition that made her famous. The Japanese Women's Everest Expedition of 1975 boasted a television crew, three journalists, four cameramen, 23 support climbers, and some 500 porters. Though Tabei’s credentials were unquestioned—she had established a new line on Annapurna III in 1970—she didn’t quite fit in with the others. She financed her way by teaching piano lessons. Her pants were cut from old curtains. She padded her own sleeping bag and fashioned waterproof gloves from the cover of her car. At home in Tokyo, her husband, Masanobu, was caring for their three-year-old daughter.

She intended to return to them. On Everest, Tabei would follow a simple strategy up the Southeast Ridge route: one step in front of the other. “Make each step sturdy,” she reminded herself. She soon encountered difficulty in the Western Cwm. On May 4, an avalanche scoured the Lhotse and Nuptse wall and entombed Tabei in her tent with two other climbers. Pinned down by chunks of ice, she couldn't get up or see—another woman's hair smothered her face—but she did manage to yank a penknife from a cord around her neck and hold it up. A support climber inside the tent grabbed the blade from Tabei as she blacked out. Slashing the fabric, punching through the snow, he summoned help. Tabei was fished out by her ankles.

Although bruised and shaken, she rallied for a summit attempt less than two weeks later, on May 16. From their bivouac on the South Col, Tabei and her team's sirdar, Ang Tshering Sherpa, rose at first light and set out for the summit. At times, wind and doubt pushed Tabei back. “The route was too steep and too long for a woman,” she later told historian H.P.S. Ahluwalia. But she proved herself wrong. Goaded on by Ang Tshering, she trudged forward, traversed to the South Summit, then balanced across icy boulders and along a knife-edge ridge to the Hillary Step, sometimes called Hillary’s Chimney. “After crossing the Chimney,” she recounted, “it was sturdy going.” After so much effort, the highest point on earth seemed “too small and narrow” for her. Exhausted but euphoric, she buried a thermos of coffee in the snow to wake the resident mountain goddess and announce her arrival.

Nearly every newspaper that covered the feat trumpeted Tabei's diminutive height (she was only four-foot-nine) and featherweight. Elizabeth Hawley, keeper of Everest records, assessed Tabei as “modest… not a great climber in terms of expedition climbing abilities,” but good enough, “a determined one.” Hawley was unenthused, writes her biographer Bernadette McDonald in Keeper of the Mountains, and “somewhat cynical about the 'first woman to climb Everest' objective.” But it was exciting. As word spread of Tabei's achievement, she gained fans across the globe. One, an astronomer, named asteroid 6897Tabei after her. They followed her career as she kept climbing, becoming the first woman to complete the Seven Summits in 1992, just seven years after it was first thought up by Dick Bass.

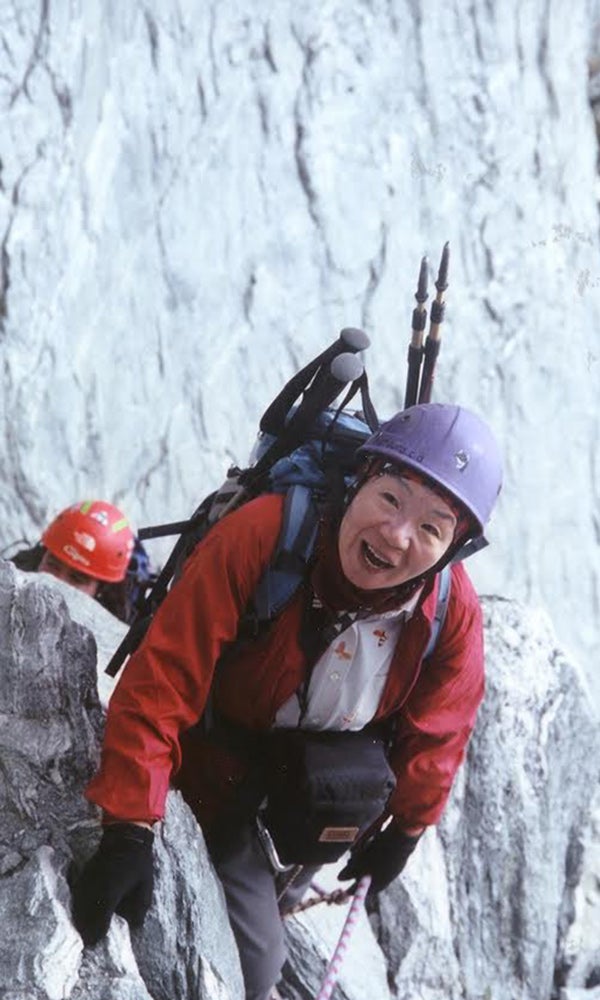

The secret to success, she said, was to remain cheerful, “because it makes everyone around you cheerful.” Still, her unstated profession affected her. Climbers live in proximity to death, and few expect to die in a bed. For Tabei, this was reason to cherish mundane moments. When her children left for school, she would grab them in a bear hug and look them in the eye as though she might never see them again. Everest was family, too, and she cared for it. In later years, Tabei became a vocal advocate for conservation and warned that expeditions were trashing her beloved peak, polluting the locals' water supply, and accelerating deforestation. As she put it, Everest “needs a rest now.”

Tabei never seemed to rest herself. By her 70th birthday, she had climbed to the highest point in 56 countries and authored seven books. Even after she was diagnosed with stomach cancer in 2012, she didn't slow until the final months. “I'm only beginning to understand my mother's full strength,” says her son, Shinya. What’s remarkable about that strength is how quietly determined it was. Tabei showed a generation of girls how to strap on their crampons and ascend above their circumstances. Her climbs remain an anthem to every mother who dreams of handing a fussy toddler over to its father and embracing a mountain.

Additional reporting by Kiyoka Ishibashi.