There’s a personal story I’ve told many times about my experience of being African American in the great outdoors.

Back in the late 1990’s I used to live in Bellingham, Washington. One afternoon, I went with a couple of (white) friends on a hike up Mt. Baker. It was a typically overcast day in the Pacific Northwest, and as we hiked, we began to feel the chill in our bones. We stopped at a lodge along the trail with a gift shop and a roaring fire. As my friends perused souvenirs, I walked over to the fire and with my shawl wrapped around me, stood there like a content cat warming my backside. Soon I noticed an elderly white woman staring at me. As I adjusted my stance under her gaze, she jumped. I jumped. Then she walked slowly in my direction. She said, “Dear, I thought you were a beautiful Indian statue!”

To this day I can’t quite remember what I said (I believe I mumbled a thank you). I think I was just confused and astounded, because in one breath she had managed to compliment me and consider me not real.

I have many stories like this. In every circumstance, I usually wonder: Has this person ever seen a black person hiking? Has she or he ever seen a picture or heard a story of someone who looked like me in a similar setting?

While I consider myself a predominately urban person (born and bred in New York), I am no stranger to the backpack and the hiking boot. I’ve had the privilege of backpacking in many different parts of the world, trekking up to 17,000 feet. For a time, I lived in Nepal with regular access to the Himalayas. I have been serving as a member of the National Parks Advisory board for the past seven years, and before that I served on the , a team of advisors who in 2009 gathered to draw out issues and priorities for the National Park Service's next 100 years. During that time, I have had the privilege to visit many national parks across the country.

But I have always been astonished at how often white people are surprised by my presence in these spaces. For the most part, people are not unkind. I’ve been asked more than once to have my picture taken, and people want to know where I come from. Still, it never ceases to leave me with a deep-seated feeling of discomfort, of being different, and feeling decidedly out of place in these outdoor settings.

I have always been astonished at how often white people are surprised by my presence in outdoor spaces. It never ceases to leave me with a deep-seated feeling of discomfort, of being different, and feeling decidedly out of place.

Today, part of my work as a writer, public speaker, and geography professor at the University of Kentucky is challenging all us to think differently about who has something to offer when it comes to the outdoors and environmental issues. But it started off as something personal.

Was that myth true—that “Black people don’t ______ (fill in the blank: swim, camp, ski, and so on)”? I didn’t think so. I watched my parents care for twelve acres of land that belonged to someone else and do so for nearly fifty years. My father cared for every part of that landscape: the flower gardens, the fruit trees, the lawn. My mother was especially skilled at growing tomatoes, basil, and dill in the vegetable garden. And she was always pointing out the wildlife to us—the black squirrels, the white deer, and the snapping turtles. While the estate owners visited on weekends and holidays, my family lived there 24/7. My parents couldn’t afford to take us on vacation to a national park, so that estate was where my brothers and I developed a great appreciation for nature.

Though the outdoors shaped my own childhood, I rarely saw black and other non-white people in mainstream coverage of the topic. Mainstream media and environmental organizations have been slow to consider or represent a large chunk of those who love wild places—and in light of the celebrations around the national park system this year, it’s become even clearer that we still have a lot of work to do.

If, as I have, you sorted through the historical narrative surrounding the national parks, the movies and books about the parks, the magazine and newspaper coverage of the parks—you’d come up with narratives that largely leave out the experiences of people of color.

Some might say that many of these works and organizations are about the parks, not people. But I would respond that the parks are about us. And that “us” has always been diverse, even if those in the positions to write the stories and make the policies have not.

The parks are a repository of memory—only, the different or more challenging parts of our history don’t get as much airtime in our national narrative. We’ve all heard about John Muir and President Roosevelt standing on Glacier Ridge in 1903. But at that same time, African Americans could not move freely in any space around the country because of Jim Crow; American Indians were still fighting about being forcibly removed from much of that park land; Hispanos in New Mexico were watching their access to these lands diminish as federal land agencies took over; and a diverse Asian population was experiencing a variety of challenges for simply being different on this soil.

The parks are about us. And that “us” has always been diverse, even if those in the positions to write the stories and make the policies have not.

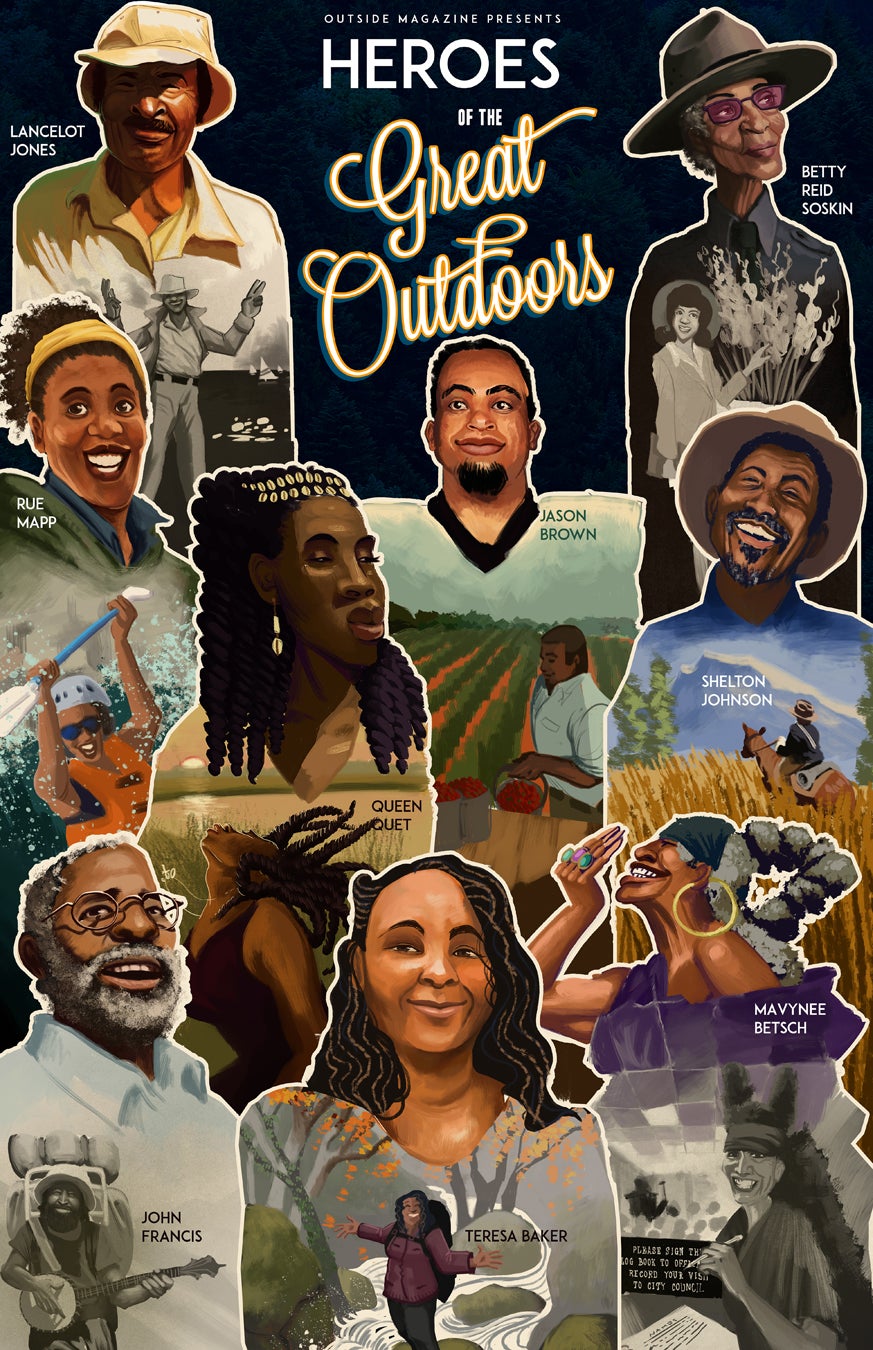

Did you know there was an all-black that was responsible for taking care of the trails at Mt. Rainier? Have you heard about , who bought three islands in Key Biscayne back in the late 1800’s and whose son, , ended up resisting the overtures of developers who wanted the land and instead made a deal with the NPS? Or , a woman who gave away all of her wealth (including her home) to environmental causes starting in the 1970s? She convinced the NPS to protect 8.2 acres of sand dunes on Amelia Island’s American Beach; her great grandfather had purchased it in the 1930’s so that black people could live on and go to the beach in Florida during Jim Crow segregation.

None of these stories are any less important simply because we might choose to universalize one piece of the parks story. That’s why so much of my studies focus on what gets left out. It’s still happening today: films like the recent National Parks ���ϳԹ��� ; mainstream outdoor media (���ϳԹ��� included) still feature a majority of white subjects; and people of color are in environmental organizations.

When I look at the majority of environmental and outdoor media these days, I don’t see me. More specifically, I don’t see a space for me. Making that space is critical: my run-in with the woman on Mt. Baker, for example, gave us a chance to engage and have our worlds shift just a little. By seeing people who look different from us in these spaces—with their histories, memories, and their possibilities—our story about the parks, and environment in general, can more fully embrace the complexity of the human experience.

How can we make this happen? I’m privileged to be part of the Next 100 Coalition—an ethnically and racially diverse group of civil rights, environmental justice, conservation, and community activists. We believe that in this centennial year, staff, leadership and community engagement with all our public lands agencies (National Park, Forest Service, Fish & Wildlife, Bureau of Land Management) does not reflect the growing diversity of our country. We have that addresses workforce diversity, landscape scale conservation, stakeholder engagement, historical and cultural preservation, and access to public lands. We met with Christy Goldfuss, managing director of the White House Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), to discuss our vision and strategize specific policy suggestions. And across the country, we continue to talk with the press and media, both locally and nationally, to tell our stories and make our case.

I believe that people tend to write and create what they know. You want a different story? Let’s get different people to tell it! Part of the challenge of representation is understanding who has the privilege of being part of these structures—and who does not. It’s pretty simple: More diversity at the table means more diverse experiences, knowledge, and ways of seeing the world.

There are folks like , who blogs for the Huffington Post and wrote two books with her husband, Frank, on their national parks experience. Or (known as Queen Quet) who, along with her community in South Carolina, was instrumental in creating the . spent 22 years walking across the U.S. to spread a message of environmental respect (and did it without talking for 17 of those years). , a Harvard-trained anthropologist, founded in Boston to create a new model for sustainability and community engagement in the city. , the NFL center who walked away from millions of dollars to start a thousand acre farm in North Carolina, learned to farm on YouTube (really) and now gives away thousands of pounds of vegetables every year. How cool would it be to have the face of this black football player on a movie or television screen? Can you imagine all the kids who would be surprised and positively impacted by that ����������?��

I hope a lot of people will go watch the movies and read the books celebrating the centennial and our national parks. I’m guessing that for many, the closest they may get to some of our grander spaces like Yosemite or the Grand Canyon is the movie theater or that book. But I also hope that there are those who will wonder why their presence in this story is not apparent; who will take this opportunity to talk about it with others; and who will not be stopped from going to experience the great outdoors wherever they live.