An Oral History of Langtang, the Valley Destroyed by the Nepal Earthquake

You've seen the images from Everest Base Camp and Kathmandu, but one village was hit so hard that it ceased to exist altogether. Half the population was buried. The others had to find a way out. This is their story.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

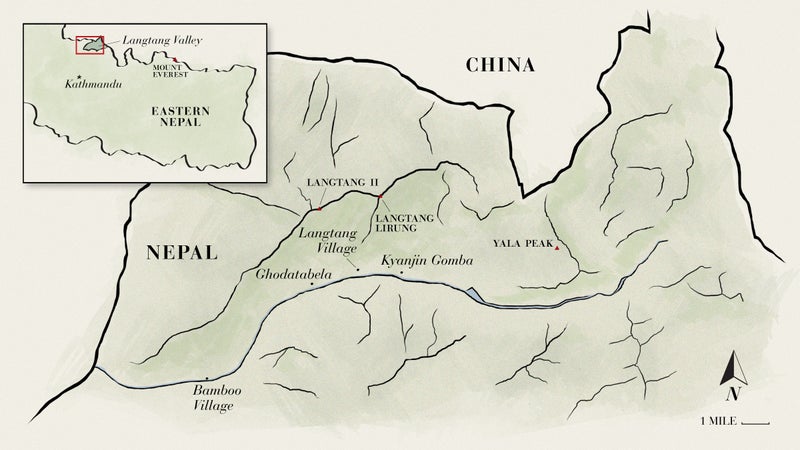

On April 25 of this year, at 11:56 a.m., local time. Half a million homes across the country were leveled and more than 8,500 people were killed, including 19 climbers and Sherpas who died in an avalanche that roared through Mount Everest Base Camp. While images of the devastation in Kathmandu were broadcast around the world, little was heard from people in the Langtang Valley, which sits roughly 40 miles northeast of the capital. The valley is comprised of 20,000-foot Himalayan peaks that tower 8,000 to 10,000 feet over several small settlements. The mountains—and the hiking, biking, and climbing opportunities that accompany such terrain—have long made the area a popular adventure destination.

By late April, with tourism season in full swing, there were approximately 600 people spread throughout the valley, including Bamboo Village, in the west end, Kyanjin Gomba, in the east, and Ghodatabela, the site of a small army outpost between those two spots. Most visitors, however, were in Langtang Village, the closest thing to a town in the valley and the location of over a dozen teahouses and a cheese factory. Langtang Village was full of locals; the night before the earthquake, many of them had traveled to gather at a monastery for a traditional ghewa ceremony, marking the reincarnation of a recently deceased valley resident.

When the earthquake struck, a combination of factors—snow-covered peaks, the height and steepness of the mountains looming over settlements, and the full occupancy of many teahouses—was disastrous. In an instant, the tremors dislodged parts of the hanging glaciers on Langtang Lirung and Langtang II, two of the area’s highest peaks. As the glaciers hurtled down, they shattered and then picked up more snow and debris. What the earthquake didn’t destroy, the avalanche did. It buried 116 houses and generated pressure waves with winds of up to 93 miles per hour—strong enough to flatten forests on the opposite side of the valley. It’s estimated that 308Ěýpeople died, including 176ĚýLangtang residents, 80 foreigners, and 10 army personnel. More than 100 bodies were never recovered. Approximately 300 people were evacuated after four days of being cut off by the numerous landslides and avalanches.

Of all the badly hit areas in Nepal, nowhere was the destruction as in the Langtang Valley. And yet, in the intervening months, few media outlets have spoken with those who witnessed the devastation firsthand. şÚÁĎłÔąĎÍř sought the surviving foreigners who had since returned home, along with Nepalis living in tents outside Kathmandu, and found a story not just of ruin in the aftermath but of chaos—marked by conflicts between locals and tourists as they attempted to collect supplies and food, a bias toward Westerners during the rescue efforts, and a disaster response that was haphazard at best.

Austin Lord (American graduate student in anthropology at Cornell University; Fulbright scholar): I’ve been working in and around the area for three years, mostly studying hydropower development and socioeconomic change. I’ve been up and down the main stem of the valley leading north many times, and three times to Langtang. This time I was with my parents in advance of my wedding, which was to be on April 30. I wanted to show them the places I was working, to show them Langtang, because it’s an incredibly diverse area.

Langtang is a true, functioning village—there are settlements throughout the valley, some permanent, some that have grown as a response to tourism. One of the things that makes Langtang so popular is that, once you get to the higher valleys, it feels similar to the other high valleys in the country, like Dolpo, but it’s far less remote. My parents had never been to Nepal before. They were pretty amazed. You struggle through the forest, then you peek into a glacial, U-shaped valley.

Colin Haley (American alpinist who was in Nepal to climb with Frenchman Aymeric Clouet): I’d only done a little climbing with Clouet before, but we both wanted to do some in the Himalayas. His wife and daughter went into the Langtang Valley with us; they were going to hang out with us for the first week, and then we were going to stay for another four or five weeks and go climbing.

Athena Zelandonii (Australian trekker and photojournalist): On our way to Kyanjin Gomba, we passed through Langtang Village, and it was gorgeous. Yaks everywhere. Women plaiting their hair. It was one of the most beautiful places I’d ever been. I thought, I’m not going to take pictures now. I’ll take them on the way back.

Aviv Rozen (Israeli trekker; former commander in the Israeli military): We’d just gotten out of the army, and I went on a trip like most Israelis do after they finish. After a month traveling around Laos and Cambodia, we wanted to trek to see the mountains, so we decided to go to Nepal. We wanted to do all the treks we could in Nepal: Frozen Lakes [Gosaikunda], Annapurna, maybe even Everest Base Camp. So, just thinking it through geographically, we decided to start with Langtang.

Dhindu Jangba (hotel owner, Ghodatabela): I was talking with Austin [Lord] at the counter of my hotel. There were a lot of other trekkers around, about 100 of them, when the hill right behind us burst like a blasting had happened. There was nowhere to run but ahead. In that narrow space, to have the mountain burst out from both sides and to be in the middle? You can imagine what it was like.

Lord: We were running like hell, then I stopped and the whole ground was moving.

Sheraph Tamang (yak herder from Langtang Village in Bamboo at the time): My wife and I left for the settlement of Bamboo Village around 8 a.m. When the earthquake came, I had no idea what was going on, and I was looking for my wife, who’d panicked and rushed down to the river. There were rocks coming from one side of Bamboo and landslides from the other. This big boulder just missed us and slammed with great force into a hotel and demolished it. There was a mule herder—he was killed right in front of us by a rock. When we saw that, we panicked and headed for a cave.

Della Hoffman (American trekker traveling with her boyfriend, Eric Jean): We watched as huge, car-size boulders came down the mountain above the village and started crushing the buildings. They were rolling right through the tops, shearing them off.

Haley: Most of the buildings in the valley are made of stacked granite blocks with very little, if any, cement. So they just started shedding pieces of rock everywhere. They basically shook apart.

Faye Kennedy (Canadian trekker): I was facing the mountains, and I could see seven yaks. It struck me as funny, because it looked like they were dancing. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw this big cloud of snow coming toward us. I pointed at it and said, “What the hell is that?”

Haley: I’ve seen a lot of big avalanches all over the world, and I’ve never seen anything like that. Normally, you’d have much more warning time, because you’d hear the noise. But with buildings falling apart all around us, we couldn’t hear anything, and we couldn’t see it coming, because there was a cloud ceiling a couple of hundred meters above the village. Most people ran and hunkered down behind rock walls and what was left of some stone buildings. I started sprinting across a meadow, which in hindsight was the wrong decision. All of a sudden, it went from being windy to being extremely windy, and I started getting blown across the meadow. Then the real blast hit.

Kat Heldman (American climber in Nepal to attempt 20,955-foot Gangchempo): There was this giant plume of white and gray, of rock and ice and snow. It looked like Mount St. Helens erupting. We all turned and started running through the village. I felt the first impact hit me, and I knew there was no way I would be able to stay on my feet. I dove behind a rock wall and crouched down.

Kennedy: I thought we were doomed. I thought it was going to bury us alive. We were down behind this wall and were completely showered with snow and debris, and everything went dark gray, almost black. Stones from the wall were falling. I remember thinking that this might be better—a quicker death than suffocating under snow.

Haley: I was flying through the air in this torrent of wind and snow, and I hit the ground a couple times and then got blown off the plateau at the edge of the meadow down a steep hill. Then I slid the rest of the way to the valley floor. I immediately got up and started running, because I had no idea if there was avalanche debris coming behind me.

Ngawang Dorje Tamang (student in Langtang Village): My mother and my cousin and I were working in the fields two hours below Langtang Village. The avalanche caught us just as we got into a cave. The three of us were holding hands, and as we looked up to the sky we saw a black cloud with dust, stones, and huge boulders revolving in it.

Karma Lachung Tamang (resident in Langtang Village; mother of Sheraph, a yak herder trapped downvalley in Bamboo Village): The avalanche was really black—it was swirling and swirling, with rocks, sand, ice, and snow all mixed up. Whoever was outside had no chance. My older daughter was right in the center, completely buried under the snow. We haven’t even found her body yet.

Heldman: Then it stopped and it all went quiet.

Kennedy: I was amazed that it became light outside. I remember saying over and over, “It’s light. We’re OK.”

The Aftermath

In only minutes, most buildings in the Langtang Valley were leveled. Hundreds of people were dead, many more injured. In Bamboo Village, Kyanjin Gomba, and other small settlements, survivors slowly began to realize just how devastating the earthquake had been. But no one was prepared for what they would find in Langtang Village.Ěý

Row Smith (British trekker on a two-week holiday with her husband): In Kyanjin Gomba, it was just chaos and devastation. Most of the buildings had completely collapsed. There were a load of locals huddled under a huge boulder, and some were quite badly injured. It was horrible. It was like a scene out of a war. It was absolutely grim. Dads sitting next to dead children.

Brigida Martinez (American climber traveling with Kat Heldman): I am a pediatric ICU nurse, so I did a lot of wound care and cleaning. We didn’t have a whole lot in the way of medication. I remember there was this little girl who had half the skin on her forehead ripped off. She was sitting there and barely even flinching.

Heldman: We started going through our bags and giving people our extra shoes and coats. I remember seeing a man standing with no shoes or socks. His head was bloody, and he was holding a baby from the village. We followed Brigida around and did what she told us to do. I thought I was watching people die. These people needed to be in hospitals, but we didn’t have that.

Haley: Right afterward, a lot of people in Kyanjin Gomba—I think mostly foreign trekkers but also some nonlocal Nepali people—grabbed their things and started hiking downvalley toward Langtang Village.

Kennedy: The trail that went to Langtang was completely broken in half in parts; pieces of it were down in the river below, and the river was littered with big boulders. There was blood on the trail, and people were beside themselves, running and crying. We could still hear the earth settle and hear rock slides. At one point, we heard a loud crack and the sound of boulders coming down. I found the biggest boulder I could and crouched down under it.

Lord: I ran through the woods along the river to find my parents. There was an incredible amount of debris still coming down. I eventually located them hiding behind a large boulder, with big rocks coming down and breaking off in all directions. I looked up the valley where you could see Langtang Village, and there was just a wall of snow. It was insane. I was standing there with Dhindu, and everyone was saying “Sabai gayo,” which means “It’s all gone.”

Sonam Tamang (student in Langtang Village; Sheraph’s cousin): Karma thought her son was dead, but five hours later they heard him groaning. Only his breath was left, but they dug him out. Karma saw people being taken by the wind that came with the avalanche. Another brother of hers was by the river with the yaks. He was trapped under a tree and was begging an old woman to help him, but she wasn’t strong enough. When they came back for him, he was already dead.

Lhakpa Jangba (owner of Dorje Bakery Cafe in Kyanjin Gomba): In Langtang Village, you couldn’t even pick up some of the bodies. They were in so many pieces, totally mashed up—like mince.

Waiting for Help

The earthquake and avalanche destroyed roads and footpaths in the area, effectively shutting off the Langtang Valley from the rest of the country. If help were to come, it would have to involve helicopters, and until they arrived people in the valley had to survive any way they could. Many in the villages tried to help each other establish shelters, treat the injured, and collect food and water, but there was controversy amid these efforts. Some locals accused Westerners of looting their houses and demanded payment, while some Westerners without supplies believed that locals were trying to profit from a disaster.

Ngawang Dorje Tamang: We stayed in a cave that night and then went down to Ghodatabela. There were two very badly injured people with us: a lady whose daughter was close to death, and her young son, who had a splinter of wood through the back of his head. His face was all swollen up, and he was saying, “I won’t die, I won’t die.”

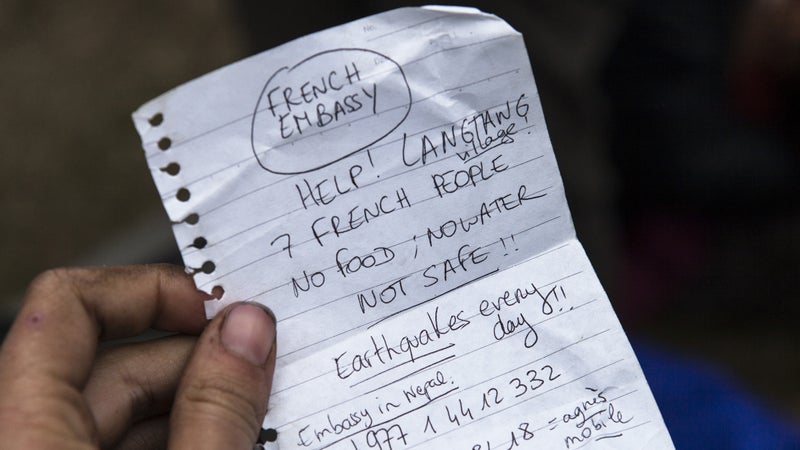

Zelandonii: When we got to a partially completed hospital above Langtang, there were already a lot of people there. Everyone set up with fires and scooted together and settled in for the long haul. There were probably 120 people or so there. Between me and my friend, we had a small bottle of Sprite and a Snickers bar. That became our sustenance.

Rozen: We decided it was time to start building camp, because we were going to stay the night there. I had the only satellite phone, so we started to send the sat signal and made contact with the Israeli insurance agency. We built a small shelter for everyone. We bought ingredients from the locals because they weren’t willing to cooperate a lot, so we just had to bribe them to get food, pots, blankets, pillows. We knew we were going to be there a few days, so we might as well make a better place to stay in. We started thinking of ways to boil the water better, to fill the bottles, to improve the camp. We decided to build a few helipads, so we needed to find a place and split the work.

Kennedy: We started fires to keep warm, and people continued to arrive. There were a lot of extremely injured people being carried, people with blood everywhere. People were beside themselves with grief, crying and wailing. At one point, one of the local men picked up a board and started hammering himself on the head with it.

Haley: We spent our first night there not really sleeping at all, just kind of leaning with our backs against this boulder. It snowed most of the night. Everyone was really on edge, and every time there was an aftershock, people would start screaming and running. I was terrified of every aftershock. We were saying that we couldn’t tell if the earth was still moving or if it was just us trembling.

I had a satellite phone with unlimited minutes, so I became the telephone booth for the village. Some of it was logistical stuff: the leaders of Kyanjin Gomba were using the phone to call the Nepalese army to make arguments for why the helicopters needed to come, but the majority of the calls were people calling family members. Each day, people would line up and have a number written down on a scrap of paper, and we would try calling. These people were crying into the phone. You don’t need to speak Nepalese to understand that.

Martinez: The teahouse owners were trying to lock up the doors and protect what they had left, and others were looking for shelter.

Video by Prasiit Sthapit

Eric Jean (American trekker traveling with his girlfriend, Della Hoffman): We had a few granola bars and snacks. We had to work out an agreement with the villagers, because they had a ton of food in their teahouses. That first night, there was a big pot of instant noodles that everyone got a bowl of. But then tourists started getting blankets and food from the houses. To the villagers, it was like we were taking their stuff without asking, though we paid them money for the value of the goods, and we shared our food and shelter with them.

Hoffman: You could see why they were upset. People had gone into their homes and taken their things without asking. That sort of started it off on a poor note. Even afterward, when tourists would say, “Hey, this is what we need, we’d love to pay you for it,” there was never a really good working relationship.

Rozen: I’ve heard of looting and I’ve heard several versions. The version I heard from one of the Israelis who was accused of looting was that he saw a house that was about to crumble completely. He ran in with a friend, and they tried to save everything they could. Not for themselves, but for the family. Bags of rice, souvenirs from the house, pictures. They tried to pull everything out in time. And apparently one of their rice bags was full of life savings from the owner of the guesthouse, and he figured they were trying to steal it.

In our camp near Bamboo Village, we basically paid them for everything. They really overpriced it, because they knew they weren’t going to stay with us the whole time, they were going to move on to another village. They were afraid that we would loot the entire guesthouse, so they took whatever they could carry themselves and sold us the rest.

Rescue

As survivors in the valley struggled to find provisions and prepare for evacuation, family members and officials tried to reach them. But with trails blocked and telecommunications down, even the Nepalese army had little success. Groups were still spread between a camp of approximately 150 people above Langtang Village and roughly 150 others below, near Bamboo Village and the army outpost at Ghodatabela; many of those in Kyanjin Gomba had descended to Langtang, though some stayed. The first helicopters to arrive were privately contracted to pick up people who had insurance policies—primarily NGO workers and foreigners—which angered many locals and uninsured tourists, who wanted to evacuate the most seriously injured. When army helicopters finally arrived, the conflict over who should go first continued. It would take four days to evacuate everyone still in the valley.

Lieutenant Colonel Laxman Bahadur Thapa (battalion commander, NepalĚýarmy): I contacted all posts in the Langtang Valley, but Langtang Village was out of contact. A soldier then called from Ghodatabela, on a satellite phone borrowed from a foreigner. He said the clouds were blue and black, and it looked like Thangsyap and Gomba Danda were impossible to access. It didn’t look good for those places.

Rozen: The first helicopter that came was a private helicopter, in the morning. There was a group of five or six Japanese and their guide, and it was the guide’s brother who was the pilot, so he came to rescue him, and then he left.

A few hours later, the first Israeli chopper came, and the pilot started explaining what was going on. He had meant to go upvalley, but they saw our camp and dropped there by mistake. There were ten Israelis, and you can fit four in the helicopter. We told him we first wanted him to take the injured and the elderly. He told us he had to take the Israelis as well, so we sent two girls and our guide, who had been hit in the head. The pilot did four rounds. The next one was two Israeli girls and an elderly American woman with her adopted family. And then another round of three Israeli guys and another round, the last one, with the rest of the Israeli guys except me and my friend.

Ashish Sherchan (executive director, Fishtail Air): An engineer in our company had a son in Ghodatabela. He obviously wanted to get his son back safely, so the helicopter went to get his son, but they had a big fight there. The engineer was inside the helicopter, and he was almost pulled out. It was chaos.

Ngawang Dorje Tamang: There was a private helicopter on the first day [Saturday, April 25, the day of the earthquake]. There was an injured foreigner, but there were more seriously injured locals. I saw one foreigner’s guide get into the helicopter, and he kicked at us from the inside so he could get his client in.

Lieutenant Colonel Thapa: The MI-17 came [on Sunday, April 26] at 6:30 a.m., and I went to Langtang Village with a Rangers Disaster Assistance Rescue Team and a team of doctors. When we landed, I started running in the direction of the army post. Snow came up to my thighs, and a ranger and a local shouted at me to stop. There were about 150 survivors gathered, some very seriously injured.

Ngawang Dorje Tamang: You could see very clearly that the army wanted to take the foreigners first, never mind who was injured. The foreigners themselves were actually saying that the injured should be taken first, then the old people, then the foreigners, then the locals. It was the army that said they had to take foreigners first.

Lord: When the first army helicopter arrived [on Sunday, April 26], people started coming down from caves. They were covered in blood and mud. They had massive head wounds, compound fractures. They didn’t have a triage system, and the policy for evacuation was NGO workers first, the rest of the foreigners and their guides next, and Nepalis last. But we arrived at a consensus on sending the injured Nepalis first. Then the helicopter didn’t come back. People were fainting, wailing, trying to figure out who was alive and who wasn’t.

The weather wasn’t good to begin with—but there’s been a lot of talk about how the helicopter system didn’t get going, didn’t make the best use of the weather window, and when the army arrived it was immediately clear they were just a Band-Aid. They came with limited supplies, no radio, and they didn’t know the area very well. Thankfully, when the next helicopter came the next morning [Monday, April 27], it was a big army helicopter, and we loaded 25 injured Nepalis and two very injured foreigners. Then only a couple of small helicopters came, and people began swarming them again. One of the pilots who came went rogue and did as many laps as possible.

Captain Sherchan: There are about 20 helicopters in the private sector, but at a time like this it’s not enough.

Ngawang Dorje Tamang: For days we waited for helicopters. The only thing we wanted was a helicopter. We’d hang from the propellers if we could. We heard from people who came out of the villages after a few days that people who had no other injuries had died asking for water.

Rozen: The others were definitely upset that the helicopter was only taking Israeli people. There was nothing we could do. We told him to take other people first, but he wouldn’t hear us. I think me and my friend that stayed behind, we were as bummed as the rest of the foreigners, because we knew they might get upset. So we discussed it with them and told them what we felt and what the situation was, but we talked to the insurance company, and they told us that as much as they want to help everyone, they paid for a few hours of the helicopter from the Nepali army and they just couldn’t rescue everyone, so they had to prioritize the Israelis first.

Captain Sherchan: To be honest, we just couldn’t meet the demand, with calls coming in from the government, from embassies, from the families. Unlike at Everest, the whole village got washed away, so there was nobody to be rescued in Langtang. The injured had already been rescued. It was people who had been stranded there because of the blockage of the trail.

Dhindu Jangba (hotel owner, Ghodatabela): If the state had been able to send helicopters the first day, then many people would have lived. Even in Langtang.

After the Evacuations

It took four days for helicopters to ferry out the approximately 200 survivors. Many slide victims elsewhere in the Langtang Valley spent a night or two in caves and made for the army post in Ghodatabela. From there they were evacuated by Wednesday, April 29. (A small number stayed in Kyanjin Gomba and were not evacuated until after a large .) Most people in the Langtang Valley were flown to Dhunche and either walked to Kalikasthan, which is connected by road to Kathmandu, or waited for another flight to the capital. Of the dead, approximately 150 bodies have been recovered—most of them locals. Approximately 150 remain buried. Today, most of those who were evacuated are still in camps near Kathmandu, though approximately 80 have moved back to Langtang Valley. While some are focused on making a new life in the capital, many more are concerned with the future of the valley.

Dhindu Jangba: After the evacuation was complete, I walked with eight or nine young men to Langtang, where my mother had been before the earthquake. We had to skirt around gullies in the ice, and there were huge chunks of the glacier, as high as a three- or four-story building. Everything was buried. There was no hope that anyone would be alive. We stayed another four or five days to recover bodies and cremate them, or place them in caves higher up where they don’t decompose. We found the bodies of my mother and her sister.

Captain Sherchan: I got to the valley about four or five days after the earthquake. The bodies of the foreigners were retrieved by the concerned embassies, but those of Nepalis were lying all around. I could see vultures all over.

Ang Gyaljen Sherpa (mountain guide from Khumbu): When we got there on behalf of Trinetra şÚÁĎłÔąĎÍř, we searched for bodies, most of which were in pieces among the debris of the avalanche. We worked all day, looking for bodies, then went up to Kyanjin for the night. We found the bodies of two French trekkers—a guide and a friend of the guide. Their faces were smashed, but the guide was recognizable by his long hair. Most of the whole bodies we found, they were naked. They’d been caught up and blown by the force of the avalanche to the other side of the valley. I’ve seen dead bodies before while climbing along the South Col, but this is the first time I’ve picked up body parts.

Norphu Tamang (yak herder and cheese-factory worker): We stayed about two or three weeks in Kyanjin and looked for bodies in Langtang every day. I didn’t find anyone from my family. My wife had gone to Langtang, and she died there. My older brother, too.

The herders want to go and check on their yaks. Half the people rely on tourism, but the other half depend on livestock, and the yaks can’t go up or down or cross the river because the trails are blocked. If someone can lead them to safety, then they can climb up to find grass. There must be five or six hundred yaks stuck between settlements.

Lhakpa Jangba: There was another avalancheĚýin Langtang Village after the main earthquake. It could have killed everyone working there, but they survived because it happened at night, after they’d gone back to camp. We could have lost another 40 or 50 people.

Lieutenant Colonel Thapa: We were conducting recovery operations of body parts in Langtang Village, where we estimated the avalanche was about a hundred feet deep, by placing salt and black tarps over the snow and waiting for the sun to melt it. But whatever had not been lifted out was lost after May 12.

Sheraph Tamang: When we went up after the second earthquake, there were no people, no yaks, just vultures everywhere. We proceeded in a single group, so no one would go ahead and take valuables they might find. When I saw Langtang Village, I found it was much worse than I’d imagined. You can’t even figure out where your house is. It’s not possible to reconstruct Langtang Village where it was.

We found 15 or 16 bodies. There were four foreigners—just bones, but we found passports in their bags. One was a Spanish girl. We saw a photo of her, she was so pretty. In Langtang Village, people only recognized their family members by the clothes on them.

We stayed there for four days. A lot of the yaks had died or were lost. The remainder were scattered all over, and we shooed them up toward the high pastures, fixing the trail as we went. I found five of my thirteen yaks and sent them toward Kyanjin. They’ll be fine up there throughout the monsoon.

We’re still worried about our future. There’s no way we can use the pastures across the Ganja La, we haven’t thought of it at all. We don’t know what’s going to happen with tourism, and there are no jobs.

Lhakpa Jangba: If Langtang Village isn’t there, there’s no importance to the area. This is the third most-popular trekking destination in Nepal. If we leave the villages, there won’t be anything left. If we stay in Kathmandu, there are no jobs, and our young men will have to go work in Malaysia or Dubai. If that happens, it won’t be possible to build the village again.

Captain Sherchan: I’ve been to that village hundreds of times over 15 years, and I know a lot of people, so I felt very sad. They were a close community, they had a good life, and now there’s no life there, nothing at all. To get back to where they were is going to take a long, long time.

Reported by Anna Callaghan, a freelance writer living in Santa Fe, and by Kathmandu-based Rabi Thapa, author of Ěýand editor of , a literary journal.