Fitness and clean living feel good, but being bad feels really good. In a radical kiss-off to our better angels, we asked some of our favorite writers to gallop with the devil and confess their most sinful pleasures. Hoo boy, did they respond.

I, Rothario

Ever wonder if river rats get all the women? They do.

I knew I was in trouble as soon as I picked up Judith at her motel in Stanley, the staging ground for trips on the Middle Fork of Idaho's Salmon River. She was gorgeous, urbane, in her mid-thirties, with long black hair. On the shuttle drive to the put-in, I snagged a long look in the rearview mirror, which only confirmed my first impression: She was hot.

I was 28. I'd worked on western rivers for nearly a decade, taking hundreds of scantily clad women on floats through the canyons. And if you're already thinking, Man, those river guides must get laid a lot, I'll tell you straight up: We do. Most outfitters forbid guides from sleeping with customers, and most river rats do it anyway. When I was 20 and working on the river, I lost my virginity with an older womanÔÇöwhile her father and her minister snored in a neighboring tent. Another time, I hooked up with a woman whose husband was along.

By now, the “initial survey” had become routine. I mentally sorted the new arrivals into couples, singles, and potential “temporary singles.” Eager to impress Judith, I chatted her up in the van. At the launch ramp, I picked her to demonstrate rescue techniques. But on the first day out, I watched with disappointment as Judith chose to ride with Chip, another guide. Over the next few days, she sometimes rode in my raft, too, but whenever she did I had to share her with an elderly couple from WisconsinÔÇöwho favored me because I looked like their son.

Finally, on our last night, I got lucky. A few of us had stayed up late, passing wine around the campfire. Judith was getting super-loaded, and we were flirting big-time. Guide etiquette requires that you get lost when you see a pal making headway, so everybody left. Not long after that, I offered to help Judith back to her tent.

We staggered over to it. I had grabbed a candle from the camp kitchen andÔÇöto add to the ambienceÔÇöI lit it next to her sleeping bag. Wined up as I was, my judgment was seriously impaired. Not only did I risk burning down the tent; I forgot that our frolicking could be projected onto the wall like Balinese shadow theater. I closed my eyes and savored Judith's embrace.

Soon enough, I opened my eyes to see that Judith's fine, long tresses had caught fire. Hoping to resolve things before the mood got ruined, I patted the flames out with my hands. Judith figured out what was happening; we laughed and got back down to business.

The next morning, I was making pancakes when Judith appearedÔÇöhung over, and with her hair in a ponytail to disguise the considerable chunk missing on one side. Nobody asked about it, so the candle episode apparently had gone unnoticed.

On the final night in Salmon, the guides whooped it up at a local bar, and Judith came along. Hoping for a repeat, I walked her to her motel. This time, though, I got shut down. We weren't out in nature anymore; the rules of civilized society had kicked back in. She said goodbye and closed the door in my face.

I heard later that Judith had gone straight home to move in with her longtime boyfriend. I tried to find consolation in her $100 tip. I'd like to think it was for services rendered. ÔÇöMichael Engelhard

Class VI Sex

Admit it, ladies: There's nothing like a man with an oar.

City girls go on wilderness river trips for the same reason British girls visit Italy in E.M. Forster novels: to kick off their confining shoes, feel the heat of the sun on their skin, and learn a thing or two about raw male energy. At least, that was my intention, and it was plenty easy to realize.

Without meaning to, my father set the stage. He remarried and decided that rafting the Grand Canyon with his new bride would be the perfect honeymoon. He pulled me along, and I gladly went, fully hoping to get some action of my own. I didn't have much experience yet; my most compelling squeeze to date had been a prep-school boy from Model UN.

After that, how can a girl not be moved by the sight of a man who has virtually no gender insecurity even while he's wearing sandals? A man with an oar in one hand and a beer in the other, who can recite a few lines of wilderness poetry and comes with high-definition lateral traps?

In river guides is to be found a population of Real Men. They're competent with a hatchet. They will safely see you through Hermit Rapid at 12,000 cubic feet per second. They're skilled with complicated knots. And no man can spend the bulk of his adult life coursing through a canyon unless he possesses something almost as irresistible: a deeply romantic nature.

So it was with a man I'll call Joe. He'd been rowing the Grand for more than a decade and was as faithful to it as an altar boy to his home church. He was tanned and tousle-haired. He was languid, but quick and strong when the river demanded it. He was peaceful. He was happy. He was simple. He was exquisite.

But river sex is not just about the boatmen, delicious as they are. It's about the strong lure of the river itself. Joe walked me back to my patch of sand after a day of rapids and a night of drift-net beer and brilliant stars. When he grabbed my elbow and kissed me, I was gone.

Dad had no idea; he was having his own nocturnal adventures. So were the cook and another boatman, as well as a middle-aged divorc├ęe and yet another boatman. A pagan mood swept through camp like a flood. Whatever rules once governed client-guide relations were waiting out the high water with the humpback chub.

Of course, to borrow a phrase from that other den of vice, Las Vegas, what happens on the river stays on the river. It would be as ill-advised to bring Joe back to civilization as it would be to bring Paolo the grape crusher home to meet the Queen Mum.

But until we part, pass me another grape. ÔÇöMs. X

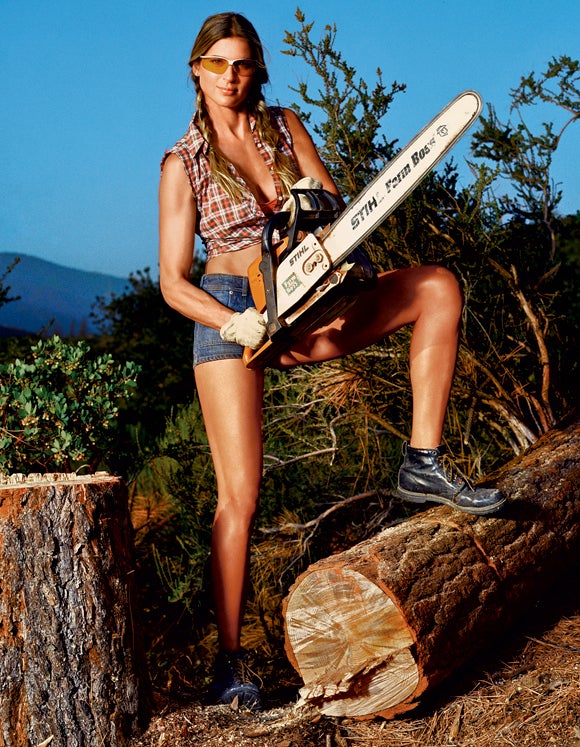

Lumber Whack

The sweet science of chopping a huge tower of wood.

First I hugged the tree. Then I cut it down.

The hug was a supplication: Fall here, and not there; but whatever you do, please don't fall on me. My embrace confirmed that this ponderosa was the biggest pine I'd ever tackled. Nine feet around at my shoulder, it rose 170 feet, as true as the mast of a sailing ship. Stored in its ten-ton body was enough energy to heat our house all winter.

As I plotted the epic crash of this colossus, my heart began to pound in anticipation. Although I pretend that felling a big tree is a necessary but regrettable task, in truth I adore the power of the saw, the thunder of the fall, and the sublime triumph of bringing to earth something that's far bigger than I'll ever be.

Back at the shop, positively giddy, I fitted a brand-new chain around the 20-inch bar of my Stihl Farm Boss saw. Then I bolted on the plate, used a screwdriver to ratchet up the tension, checked the reservoir to see that there was plenty of chain lubricant, and filled the fuel tank. I grabbed my safety glasses and earplugs and went to work.

The Stihl roared to life and bit hungrily into the ponderosa, spraying shavings with an eagerness that seemed feral. I guided the blade slowly through the lines I'd sketched with a marker on the rough plates of sienna-colored bark. To my great pleasure, these cuts produced exactly the notch I wanted, a foot-deep, foot-wide wedge all the way across the side of the tree, facing its landing site. Now that the path of least resistance was established, I fished out the wedge and moved to the other side for the coup de grâce.

I began making a deep cut aimed at the notch. At the moment of truth, when there issued from the tree an almost imperceptible shudder of forward motion, I pulled out the blade and escaped. The ponderosa hesitated, as if making some final decision. Then it surrendered to gravity and began its fall in an elegant arc toward the precise place I'd chosen for it. My cheer was drowned out by a boom that was four times louder than I'd expected, a primal whump that jumped from the ground straight into my brain.

Even before the tree's limbs stopped tossing in its final throes, I began to feel the regret of seeing a great thing leave the world. But this tree was doomed before I cut it down. It was infested with bark beetles, and if they didn't kill it, the meandering river would have taken out the bank around its taproot in a year or two.

Scattered all around the trunk were pinecones knocked loose by the crash. I gathered up a dozen and dropped them on the floor of the forest, far away from our reckless river, at a spot where the sun was shining through. ÔÇöBill Vaughn

Crunch Time

When critters are getting eaten, I'll be there.

I like to watch things get eaten. I know this minor outdoor pastime is not entirely healthy, but it scratches an itch, somehow. On a river I can get so absorbed in watching trout feed on mayflies that I forget to fish. When I lived near the Clark Fork River in Montana, I sometimes would go to it without my fishing rod and observe the armadas of newly hatched mayflies as they floated downstream over pods of hungry rainbows. I would choose a mayfly that looked especially lucky and root for him to make it through. (Often I imagined the mayfly was me.) With amazing predestination, he would float unscathed past the sinks of trout mouths sucking in his pals around him. My mayfly's wet wings began to flutter, he was about to fly awayÔÇöand then GULP! Too bad! I used to put minutes, quarter-hours, half-hours into this game, like ever larger sums into a slot machine.

I've watched sparrows eat grasshoppers in a Missouri River parkÔÇöa good-size hopper can give a sparrow quite a tussleÔÇöand peregrine falcons eat pigeons in Brooklyn, and bald eagles swoop down on spawning salmon in Glacier National Park. Once an outdoor-writer friend in Missoula, Montana, told me that in late summer in the Mission Mountains, north of town, there is an enormous hatch of ladybugs on a particular mountainside, and sometimes officials have to close the area to hikers so they won't meet up with the grizzly bears that come to feed. A grizzly eating masses of ladybugs is a sight I'd love to see.

During a reclusive period, I spent a couple of months by myself at a campsite in northern Michigan. In the evenings I fished, and in the afternoons I read Proust. I was proceeding through a volume of Remembrance of Things Past when I noticed, in the sandy soil of the hilltop where I sat, several cone-shaped holes. These were the holes of the ground spider, an architecturally gifted predator who traps insect pedestrians. The ground spider excavates a hole and gets the grade of its sides just right, and then he waits under a thin layer of sand at the bottom. When an ant or beetle steps in and tries to scramble out, the ground spider instantly throws spurts of sand up the sides so they become like a fast-moving down escalator hurrying the victim to him.

As Proust's narrator, Marcel, offered yet another multi-thousand-word disquisition on the suspected infidelities of his girlfriend, Albertine, I counted on the ground spider to provide an action sequence or two. Sure enough, pretty soon an ant came along and fell into the hole, and the exciting part began. Once a bee walking on the forest floor tumbled in, and you never saw such a fightÔÇöwings buzzing, sand flying. During slow periods, I was not above helping the plot along by tossing in a deerfly that had become entangled in my hair. The thoughtful way the spider dined afterwards, with just his victim's rear legs sticking up above the sand, revealed deep truths about storytelling. Remembrance of Things Past, ground spider version, is the translation I recommend. It makes the underlying who-eats-who easier to understand. ÔÇöIan Frazier

Breaking All the Rules

At Walden Pond, they forbid inflatable pool toys. Sounds ripe for disobedience, don't you think?

Eleven-thirty a.m., July 10. It's already 85 degrees, humidity rising. We park the rented Ford Mustang illegally on Boston's Route 126 and slip into Walden Pond State Reservation through the white pine woods in the park's northwest corner.

My friend Jake and I are engaged in an act of protest. Last night, boozing at Boston's 21st Amendment bar, we decided that these were heavy times, burdened with laws needlessly forbidding our God-given rights. What rights, we couldn't think of right off, but we pledged to be “men first, and subjects afterward,” as Thoreau put it in his 1849 essay “Civil Disobedience.”

Indeed, we knew, Thoreau's old home had itself been snared in petty regulations. Sure, they were enacted after a weighty preservation battle against developers in the early 1990s, and sure, they mitigate the damage of weekend crowds that can hit 10,000 a day. But they do so at the expense of our civil liberties!

You doubt me? Behold the long list of shalt-nots at Walden: No dogs, no alcohol, no fires. Neither “boats powered by internal combustion engines” nor “novelty flotation devices” shall profane these waters. And P.S.: No swimming all the way across the pond.

There was only one thing to do. We would smash as many of these restrictions as possible, in a single act. We would captain not one but two novelty flotation devices all the way across the pond. And we'd do it in plain view, on a crowded day, drinking, smoking, and wearing Hawaiian shirts.

Now we're huddled in the sumac on the 62-acre lake's northwestern shore, not far from Thoreau's cabin site, and the idea seems as sound as ever. Which is to say, we're still drunk. While Jake turns blue blowing up Emerson and HorseyÔÇöhis green Dragon Super Jumbo Pool Rider and my yellow Seahorse Ride-OnÔÇöI sort through our provisions: Sunbrella parasol; battery-powered hand fan; stash of wooden-tipped cigarillos; and, not least, our high-capacity beer-drinking device, improvised from ten feet of clear plastic tubing and a Boston Red Sox Styrofoam cooler.

“How far you think that beach is?” I ask Jake, waddling into the water with swim fins.

“Maybe half a mile,” he replies, struggling to center his 180 pounds on the pool toy.

“No problem,” I say, hugging Horsey's neck for stability.

And with that, we're off.

And we're still off. Ten minutes later, Jake is barely 15 feet from shore, and a crowd of mothers and children has gathered on the bank to take pictures of him. He is half underwater and making deep strokes on his starboard side. Emerson spins in place.

“What's going on?” I yell.

“I'm using the J-stroke,” he assures me.

“Looking good, my man!”

Forty-five minutes later, we're in the middle of the pond, and no ranger has motored out to jail us. This is OK. We'll surely have to explain ourselves when we get closer to the ranger station on the crowded main beach. But the very contraption that powers our voyageÔÇöthe beer-drinking deviceÔÇöis now threatening to sink us. Each time I paddle, the blade catches on the ten-foot-long tube snaking from the Styrofoam cooler to my helmet. My head jerks to the side, causing Horsey to tip, affording me a clear view into the pond's 100-foot depths.

Jake flippers back lazily. “Looks like we have to make the tough call,” he says.

“Disconnect the slurpie tube?” I ask fearfully. He nods.

As the beer dribbles away, so does hope that our one good act will “leaven the whole lump,” as Thoreau put it, quoting the Bible. Over the next half-hour, a few boaters come by to compliment Emerson and Horsey, but none cares to hear about our mission. The last straw comes when three old Russian ladies snub my invitation to join our flotilla, dog-paddling away as if no one had ever offered them a slug of beer through a ten-foot hose.

Then, hope! Two hundred yards off Main Beach, a lifeguard paddles a surfboard out to reprimand us. “You know you aren't supposed to take inflatables on the pond,” she says, looking inconvenienced. “And there's no drinking, either.”

Jake, a trained lawyer, argues in our defenseÔÇö”We're not bad men…”ÔÇöbut she'll have none of it. She turns around midsentence to power back to her chair.

It's clear that our enterprise has failed: When we hit the shore, young children start bouncing on Emerson and Horsey. But thenÔÇöfinally!ÔÇöanother young lifeguard ambles into the crowd.

“You know you're not supposed to do that,” she says, pointing at our soggy stuff. We nod. “But I'll let you go, 'cause your inflatables are so cool.” She smiles and walks away. As if we were just some goofball drunks! We aren't going to jail. We won't even get to make a statement!

No, our protest is sunk. We will need to return with props that won't overshadow our message, something that will truly encourage people to, as Thoreau once wrote, “cast your whole vote, not a strip of paper merely, but your whole influence.”

“Dude,” I say to Jake. “We gotta come back with a hovercraft.”ÔÇöEric Hansen

I Love My Hummer

Big wheels keep on rollingÔÇöover everything in sight.

It's hard to admit but harder to deny: Some part of us enjoys nature only when we're grinding her face beneath the heel of our jackbootsÔÇöor, say, the skid plate of a $120,000 Hummer.

It was the lure of sweet abuse that carried me to southwestern Pennsylvania's remote Nemacolin Woodlands Resort and Spa, a swank getaway named for an Indian scout, allegedly, not an intestinal worm. Nemacolin is one of those retreats where wild nature is tucked discreetly behind the faux ch├óteau and around an ever-expanding set of golf courses. Bill Clinton and George Bush the Younger have both chilled here, and stressed-out CEOs routinely arrive on the private airstrip to sample skeet shooting, paintball, andÔÇönew this springÔÇöan Off-Road Driving Academy offering access to a fleet of aircraft-grade-aluminum-plated Hummers.

For $275 per two-hour session, would-be corporate chieftains like me can get out our ya-yas popping ollies on pristine ridges, conquering the resort's Rock and Crater obstacle courses. Yes, I'll be nipple-clamping Mother Nature using the “brute strength of the Hummer,” as Nemacolin puts it, but according to the Off-Road Driving Academy's Tread LightlyÔäó principles. Which means I'll somehow get the “ultimate off-road-driving rush” and learn how to “minimize erosion” at the same time.

Apparently there's a right way to rape and a wrong way. In either event, we'll be raping in style.

On the morning of my ride, the hot mugginess from the previous night's downpour is no match for the Hummer H1's arctic air conditioner. I've got a CD changer for my OutKast collection, and enough cupholders to keep the martinis of my theoretical vice-presidents happy through the big muddy. Riding shotgun is my coach, Jordan. A handsome guy in his twenties, Jordan coaxes me toward the vehicle's more subtle pleasures. “Off-roading in a Humvee,” he intones gently, “is more about power than speed.”

So it is. Out on the mile-long Crater course, the road is a sluice of squishy mud. Spinning deeply in black slop, only one wheel has any real grip on the ground. I can literally feel the onboard computers reallocating the massive torque as the Hummer works itself onto one then two tires, coming out of the muck like a fat man from a lawn chair.

That was sweet, in a power-mad sort of way, but soon I'm battling to keep my tires out of two-foot-deep ruts as soft and thin as yogurt. Jordan guides me toward my first moment of off-road Zen. “Don't fight the machine,” he murmurs, as if to say, Be the Hummer.

This is how powerful the low-lock setting on a Humvee is: At one point I come to the lip of a ledge and drive the vehicle out and over a 45-degree, 20-foot drop, before slamming down. Not since I first rappelled have I felt this mix of fear and uncertainty. I let go of the brakes and, just as my guru predicted, the machine quickly seizes the ground and moseys down as amiably as a giant armadillo.

There's a kind of┬áWhen Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth┬ápleasure in zipping through nature unfazed by anything wet, thick, tilted, or rocky. I hop out of the Humvee with a bowlegged cowboy swagger and a Ronald Reagan aw-shucks grin. But after our final boulder descentÔÇöI have to be “spotted” on that one, my teacher calling the shots from the sidelinesÔÇöJordan can't help but take pride in the giant construction effort that went into making the final rock pile doable.

“They take a plywood cutout of the undercarriage of the Humvee and slide it down the rocks,” he says. “If it's too deep, they add another rock. If it's too high, they use the backhoe to smash it down.” Those swampy gullies I forded earlier? They were all undergirded with concrete to provide solid underwater traction.

That's right: Far from harming Mother Nature on this ride, I was hardly even touching her. It was like showering in a raincoat. Or some other prophylactic experience like that. ÔÇöJack Hitt

99 Bottles of Beer in the Tent

Why camping and alcohol are always a good mix.

Camping can theoretically be performed sober, but as far as I know, no one's tried it. For many of us, camping is essentially an elaborate drinking ritual. My own preference is red wine by the fireÔÇöwhite wine, backlit by flames, becomes indistinguishable from Gatorade. But canned beer is the archetypal camping beverage, something that, like the sleeping bag and the Sierra cup, falls under the heading of “essential gear.”

Beer is particularly pleasant if it can be cooled in a tumbling stream and retrieved dramatically, with frigid mountain water dripping off it like you see in the commercials. My brother not only puts his beer in the stream but frequently goes over and checks it, the way some gardeners constantly fuss with their tomatoes. It's as if he's cultivating his brew.

Beer will get you through times of no civilized shelter better than civilized shelter will get you through times of no beer. The alcohol takes the edge off what otherwise is a physically uncomfortable experience, marred by bugs, snakes, rocky ground, bad food, unspeakably rank Porta-Potties, and nearby campers who want to come over and share their elaborate personal theories about the “real causes” of the War of 1812.

The big problem with drinking and campingÔÇöor is this the greatest glory?ÔÇöis that it's difficult to judge your limit. The woods are innately disorienting, so you can't tell whether your stumbling gait is a result of topography or intoxication. You hear strange noises: Is that nature, or just the booze? When you're by the fire clutching a beezo or a good bottle of wine or some tequilaÔÇöor perhaps all threeÔÇöyou sense that you're doing the right thing in the right place. My friend Angus says, “It's like drinking in a padded cell. You can't get in trouble.”

In the summer of 1978, I was hitchhiking through the Smoky Mountains and nabbed a ride from a group of Army grunts on leave. I went along as they hiked five miles into the deepest woods, lugging a military-surplus cooler jammed with cheap beer on ice. That cooler probably weighed 200 pounds, and the endurance of those young soldiers as they marched up a winding trail, straining under the load, made me proud to be an American. Where do we find such men? For them, camping was a battle, and they'd brought plenty of ammo.

Yes, there are those who disapprove of such activity, who believe that the whole point of camping is to refresh our physical and spiritual selves, to feel fully alive and virtuous. And it's good to have one such person aroundÔÇöbecause somebody has to get up and make the coffee. ÔÇöJoel Achenbach

Sticky Fingers

Confessions of a teenage taxidermist.

One day when I was 12, I sat eavesdropping and snickering at the top of the stairs as my parents discussed some creepy kid in our Jackson, Mississippi, neighborhood. The snickering stopped when I realizedÔÇöcue melodramatic organ musicÔÇöthat the creepy kid was me.

“This is awful,” said my dad. He was a pathologist, which means he worked on dead bodies and tissue samples all day. He knew awful.

“Well,” my mom rationalized, “maybe this will lead to an interest in surgery later on.”

They were co-retching over my decision, which I'd announced out of nowhere, to take up taxidermy as a hobby. Understandably, they wanted to know why. Why had I decided to become a pint-size ghoul? Was it something they'd done?

No. It was something I'd done. And the really weird part is that I'm glad I did it. Even today, with my fingers free of their long-ago aroma of bird blood, I recall my motives, which seemed pretty sound at the time. I'd had a run-in with the juvenile authorities, and I needed a Boy ScoutÔÇôflavored hobby that represented a return to innocence. I chose taxidermy because…well, I guess because I was a weird little bastard.

But I also blame Teddy Roosevelt. Around this time, I read a biography of T.R. and eagerly noted that the bully president had been a boy naturalist himself, one who shot and stuffed his own birds and small animals. Since I came from a hunting and fishing family, this seemed like just the thing. I saw myself loping through the woods with a shotgun and a sketchpad, “collecting” specimens as I filled my expanding lungs with clean, woodsy air.

So I bummed some money off Mom, sent for a mail-order taxidermy course, and raided my dad's old autopsy bag for necessary tools, including a razor-sharp scalpel, curved needles, and all the gauze I could grab.

Have you ever tried taxidermy at home? No? Well, believe me when I say it ain't easy. To mount a bird, you start by making an incision down the front and skinning the thing in one clean, undamaged pieceÔÇöan act that requires adult dexterity and lots of patience. I had neither, but I did have a powerful pellet gun that I used to collect all too many sparrows in nearby backyards, and for naught. Skinning was too difficult. Months passed, but as the carcasses piled up, I never produced a feathered friend suitable for mounting.

That changed the next year, when Dad moved the family to Garden City, Kansas. Uprooted to this distant prairie outpost, I plunged into more serious bird hunting (doves, pheasants, and ducks) and became grimly serious about honing my taxidermy skills. Eventually I got it. My first successful mount was a sparrow that I stuffed with a lumpy artificial body, and whose glassy-eyed look of reproach (“Why me? Why this?”) haunts me still. I mounted a starling. Then a wood duck. My crowning achievement came when I mounted a flying pheasant as a Christmas present for my oldest brother. It was a damn good job, too, and you should have seen the look on big bro's face when he opened that box!

And, yeah, there were bad moments. Like the day a bird-phobic member of my mom's bridge club rounded the wrong corner in our house and nearly had a thrombo. Or the day I found a dead coyote by the Arkansas River and dragged it home, thinking I could mask the stench with hair spray and tan it into a fine, soft rug.

Before long, I quietly transitioned out of my taxidermy phase for good, but I still take a measure of pride in my work. These days, I don't huntÔÇöin fact, I strive to make my backyard an irresistible bird sanctuary, to offload the karmic debt. And sometimes, when it's early and the finches are just raising their voices in song, I'll look at my hands, think about what might have been, and quietly say, “Ewwwww.” ÔÇöAlex Heard

Boom, Boom, Ain't It Great?

This lollapalooza says guns and explosives are a blast.

Shooting cans, paper targets, and clay pigeons can be satisfying. But nothing quite compares to the tingly bliss of firing at something that is itself an explosive, giving you the unmatched thrill of sending fireballs into the sky and shaking pictures off farmhouse walls a mile away.

This is why I recently traveled to Moscow, Idaho, for a personalized day of blastitude with 48-year-old pyrotechnics whiz and landowner Joe Huffman, who created Boomershoot, an annual gunfest that, every May, draws 200 people to his family's farmland to detonate 2,000 pounds of explosives by shooting them. Sadly, I missed that. But, nice guy that he is, Huffman invited me up for some solo action.

A self-described “gun nut,” Huffman works by day as a researcher at a government-owned national laboratory. In his leisure hours he's a National Rifle AssociationÔÇôcertified shooting instructor who holds a federal license that allows him to manufacture high-explosive targets, all of them lovingly hand-mixed (think Dirty Harry meets Ben & Jerry's) in a steel shed that houses enough ingredients to make hundreds of fireballs.

I know. It sounds wrong on so many levelsÔÇöthe guns, the noise, the NRAÔÇöbut what can I say? Sometimes a girl just has to get the kinks out, and firing guns is a great way to do it.

Huffman knows my type. On the day of my arrival, he lets me help make the explosives, a process that brings back memories of baking snickerdoodles with MomÔÇöminus licking the bowl. I easily slide into the routine: measuring out potassium chlorate, blending the secret recipe in a KitchenAid. Properly combined, the mixture has the consistency of tabbouleh. We pack it into cardboard tubes, four to eight inches wide.

It's only when we stack the tubes in milk crates and load them into a minivan that I get a bit apprehensive. I try to act blas├ę when, en route to the blast site, the van fishtails on a muddy hillside, hits a small tree, and gets stuck in the mud. The tree is sacrificed. Huffman cuts it down so he can dislodge the van, and then, to my distress, we speed down the hill and jolt across a creek before reaching the field where we plant the targets.

When we drive back to the shooting area, 380 yards away, Huffman sets me up with a loaner gun: a svelte .300 Winchester Magnum with a megascope to die for. He rests it atop a sandbag on a small plywood table; I sit on a folding chair and prepare to fire.

Attempting to center the crosshairs on a distant six-inch cardboard disk, I regret my earlier double latte. But I hold my breath and, at the very moment my target bobbles into the center of the scope, squeeze the trigger. No kaboom.

“You're three inches to the left,” announces Huffman, who's watching from a tripod-mounted scope behind me. My next shot is followed by enough fire and brimstone to fill the horizon with smoke. I dance a maniacal jig. I'm drooling for more explosions.

I get lots of them when we go in for the “cleanup,” a process in which we both assume a “warrior” yoga pose and I get to fire an AR-15 at a dozen targets only 20 yards away.

I've shot guns in the past. I was the top-rated ten-year-old with a .22 at my day camp. I took skeet shooting as a phys-ed course in college. And for me, the undeniable truth is thatÔÇöin the right context, of courseÔÇöblowing things up with semiautomatic rifles has only one real downside: At some point you run out of bullets. ÔÇöLisa Anne Auerbach

Coca Fiend

There's nothing as invigorating as a good chew.

I got hooked on coca leaf ten years ago, crossing an unmapped part of the Peruvian rainforest. Late in a day of falling into waist-deep slime, being bitten by ants, and clawing up mudslides, my expedition mates, our porters, and I crawled under a rock to escape the cold, driving rain. Huddled together, watching darkness fall on vertical swamps, it was easy to imagine how the last foreign visitors might have died out here.

The garbage bag of coca came out, big as a bed pillow. I'd been told by our German-Peruvian expedition leader that it was more important than food. The leaves smelled reassuring, like dogs' paws. I learned how to grab a few leaves, pick off the stems, fold, and stuff the wad (bola) between my molars. I added a few crumbs of mineral lime and the alkaloids in the leaves were activated. My lips went numb, and, subtly, things began to seem less dire. Soon we pushed on, miraculously finding a place to camp.

Moments of grace come easier if you're acullicando, as the Aymara, descendants of the Tiwanaku empire of Bolivia and Peru, call chewing coca. Who cares if you look like a green-drooling goat? Coca accompanied me on a walk from the Peruvian coast to the jungle, leaving a horizon behind each day. It made it possible for me to dance as a devil in the Gran Poder (“Great Power”) festival in La Paz last June, where 45,000 costumed revelers pour through the city's streets to a heady mix of music, alcohol, and spiritual devotion. Friends warned against trying this daylong ordeal only 48 hours after landing at 12,001 feet. But I'd been a devil dancer four times already, and I'd be damned if I would sit it out. So I found a great tin maskÔÇöa skull with a knife stuck through itÔÇöand made a 12-cent investment in coca. Twice what I needed, but in the Andes, coca is for sharing, and the rigors of the dance make chewers of abstainers.

Compared with cocaine hydrochloride, the powdered drug made from it, coca leaf is relatively mild. It's also nonaddictive, and still legal in most of the Andean region, where it grows. It's definitely an antidepressant and endurance enhancer; it's used to treat ulcers and altitude sickness. If you chew all day, you get quite a boost, but you also get your daily requirement of calcium, iron, and vitamin A.

Of course, it may be the transgression I love most. I used to smuggle some coca leaves home through the Miami airport every summer. Then I learned it's a Schedule II narcotic, the same category as cocaine. That's crazy. I firmly believe coca should be legal all over the world. Things go better with coca. Isn't this as good a definition of a sacrament as any? ÔÇöKate Wheeler

Fine Liner

A roughing-it guy gets fancy aboard the Queen Mary 2.

If the prospect of booking a cruise ship evokes in you an edgy, nonspecific queasiness, then the Queen Mary 2 is an ideal choice, because she is not a cruise ship. She's an ocean liner, as aficionados will explain to you once, then correct you over and over with steely impatience should the slander continue.

Ocean liners are elegant transports for elegant people. Cruise ships are floating budgetels for sunburned party dudes who pass out in the hot tub. Ocean liners are built stronger, faster, sleeker, and more stable, and they cost about twice as much per square foot as a cruise ship. Christened by Cunard in 2004, the QM2 cost a whopping $800 million.

I knew none of this before I boarded near Fort Lauderdale. I wish I had, because my dread about being trapped with cruise-ship bozos would have been replaced by a more accurate dread of being trapped with ocean-liner snobs. But the truth is, neither of these demographics fits my travel philosophy, which is about embracing back-of-beyond destinations, unstable governments, and the sort of uncertain, primitive conditions that I truly love.

Or thought I loved. I'm not so certain anymore. Eleven days aboard the QM2 severely challenges one's roustabout sensibilities and causes even veteran trekkers to feel vaporous, even traitorous.

I'd been invited to lecture on fiction writing as part of the ship's Oxford Discovery Program, described in brochures as an “ambitious series of educational presentations by some of the world's best-known scholars.” (Shows how much they know.) The QM2 had been in service for only a few months when she arrived in Lauderdale, and there were procedural gaffes typical of all shakedown cruises. The boarding terminal was overcrowded, and pissed-off, affluent passengers vented by stomping on the toes of us lower-deck types who were wearing Birkenstocks. Because I was, technically, an employee, the staff couldn't find my name on the passenger manifest. That night, for the same reason, the French ma├«tre d' refused to assign me a table in the Britannia Restaurant, where 1,300 or so irritable paying patrons had descended.

But it's impossible to stay crabby aboard the QM2. The ship itself is an architectural marvel, a floating work of art. The QM2 is the largest passenger ship in historyÔÇö169 feet longer than and twice as heavy as its sister ship, the Queen Elizabeth 2. There's a shopping promenade on board, a casino, more than a dozen restaurants, a superb spa, pubs and bars, exercise facilities, and just about anything else you'd expect to find in Palm Beach or Paris.

The first couple of days, I explored the behemoth, got lost, then explored some more. By the third day I'd not only adjusted to life on a liner, but I was coming to enjoy it, God help me. Afternoon tea became an unexpected pleasure once I found out you didn't have to drink tea to participate; every day, the staff served tiny sandwiches filled with interesting stuff like cucumbers, and it was relaxing to sit outside on a deck chair, plate on one knee, bloody mary on the other, and engage strangers in conversation. The couple of times I dumped my plate or spilled my drink, they pretended not to notice. Now, that's class.

A watershed moment came during one of several private cocktail parties I was invited to. It was held in an upper-deck lounge, a room of leather, varnish, and brass, walled with hurricane glass so that the moon outside, blue with sea haze, seemed to match our speed and course. I was wearing a rental tux: a slightly baggy white jacket, red bow tie, pressed black slacks. I'd never worn a tux before, and whenever I saw my reflection in a mirror, it took a second or two before I realized that it was me, and not some exÔÇôpro wrestler on his way to a promoter's wedding or a wake.

All good trips acquire their own rhythm, and I was soon enamored of my routine. Each morning, my cabin steward would tap politely and I'd open the door to find breakfast served on fine china. There was an abundance of daily recreational activities: yoga, watercolors, golf, quoits (whatever that is), dance lessons, blackjack, shuffleboard, trivia contests, and bingo. I took salsa lessonsÔÇöfun. I attended a wine tastingÔÇölots of fun. I dedicated my mornings to working on my laptop and my afternoons to exercise, counterbalancing whatever overindulgence I had planned for after sunset. Deck 7 is encircled by a teak outboard promenade, and it's a good place to jog. Six laps is just over two miles.

After dark on the QM2, the ship is devoted to exactly what she represents: the tasteful opulence of a long-gone era. Everyone I met looked forward to nights at sea. I did, tooÔÇöa shocker, because I've spent a lifetime dodging pomp and dressing any damn way I please (usually shabbily). But the QM2 really does have a grace about her that elevates; plus, some of the theme nights were just too good to miss. My favorite was Pirates Night, complete with ship-provided buccaneer garb for any guest who wanted to attend. I chose to watch. It was sufficiently bizarre to see men and women in their late sixties and seventies tottering around the decks wearing eye patches, death's-head do-rags, and plastic hooks while muttering, “Avast, matey!”

Of course, I had a costume fixation of my own: Late in the voyage, I decided to plunk down $600 and buy my own personally tailored tuxedo. The ship's seamstress did the fitting, and the garment came out beautifully. The next night, standing among champagne fountains, I felt right at homeÔÇöalmost Bogart-like, because I'd been advised to select a white jacket, very much like the one in Casablanca.

“Tropical dress,” I was told.

Who am I to argue with the tailor of the Queen Mary 2? ÔÇöRandy Wayne White

Excuse My Prop Wash

The joys of jet-skiing like a slob. Editor's note: All events in this story are true. Some are more true than others.

To: Bill Gates, Microsoft Corporation

Seattle Public Schools

Audubon Washington

University of Washington crew

Kirkland Parks and Community Services

Please allow me to express regret for the inexcusable behavior exhibited by me and my associate Scott earlier this week on Lake Washington. (Scott asks that I not use his last name. Frankly, I don't know what it is. To his friends, he's known simply as “Frickin' Scotty.”) It has come to our attention that a number of shoreline residents and lake recreationists have expressed a desire to identify the “two clowns on jet skis” who caused such irritation and distress last Saturday.

We are those clowns. We write seeking both forgiveness and avoidance of legal action.

In our defense, let me say that Nate the rental-shop guy purposely put us in the water with two Polaris Freedoms, the fastest machines in his fleet. “You're gonna like these bad boys,” he said, running his hand over the Freedoms' electric-blue cowling.

That we did. Perhaps too much.

First, to Mr. Gates: We're sorry about buzzing your lakeside mansion. Scotty and I only wanted a closer look, and once inside the security perimeter, those white buoys proved too tempting not to slalom. Regrets also to the Seattle school district for the lewd gestures exhibited by me in a moment of irrational exuberance while pacing a school bus on the Highway 520 floating bridge. I understand that school officials are concerned about the corruptive effect of my gestures, but I'm confident the students were educated in nothing more than the ability of a twin-cylinder wave rocket to “book it” across a clear stretch of glassy water.

To the UW crew and the bearded dude in the kayak: I so did not see you. Nate tells me he knows a guy who does killer fiberglass work on the side. I'll hook you up.

About the harassment of Canada geese: That was Scotty. He says he's sorry. Sort of. “You walk around with a hammer for a couple hours,” he tells me, “you start looking for nails.”

As for the woman whose white-tablecloth picnic was “utterly ruined” by the “maddening whine” of our machines at Waverly Beach Park: Frickin' Scotty again. Once the wind kicked up, he got some wicked airs off that tasty chop. The funny thing is, when you're actually out there riding, you can't hear the noise, 'cause the wind is rushing so fast past your ears. Thus: not our fault.

Nonetheless, as a gesture of repentance I have made an anonymous donation to the Noise Pollution Clearinghouse. Scotty pledges to cut a check to the Audubon Society as soon as he gets paid for his last roofing job. And we both promise to have absolutely no fun on the water for the next 12 months. ÔÇöBruce Barcott

Hog Wild

I stuff my face with charred, greasy pork. Got a problem with that?

Like most men of middle age and modest culinary expertise, I'm big on grilling animal fleshÔÇöthough I don't restrict myself to summertime conditions or trivial cuts of meat. (Hot dogs? Please.) I have braved a hailstorm on Thanksgiving Day to barbecue a turkey. I've stood in half a foot of snow while smoke-roasting a Christmas ham. Through it all, I had never suffered even a twinge of remorseÔÇöuntil my girlfriend and some buddies bought me a Weber Ranch Kettle and my life took a turn for the compulsive.

The charcoal-fired Ranch Kettle is to conventional grills what Shaq is to peewee hoopsters. Priced at $1,099, with four wheels and a bulbous black lid, the thing is four times larger than a standard backyard rig. With 1,104 square inches of cooking space, it's vast enough to handleÔÇöshould the need ariseÔÇöhalf a dozen rib roasts or 27 game hens all at once.

Presiding over a grill is like commanding an army: When you have this much firepower, you feel compelled to use it. Once I had the Ranch Kettle on my patio, the charring of increasingly formidable carcasses began consuming my nights and weekends. The neighbors started to whine about living downwind from a smokehouse; my kitchen was reduced to a glorified pantry, used for almost nothing except storing condiments and beer. After several months on the Ranch Kettle diet, I felt like a human sausageÔÇöand my dog, after feasting on a metric ton of scraps, resembled an overstuffed ottoman.

Arguably, I should have stomped on the brakes. Instead, I hit the gas. Among barbecue fetishists like me, pork is the One True Meat. So, having already tackled loins, ribs, chops, and butts, I decided to devote a summer holiday weekend to roasting an entire side of pig.

Though my Brooklyn neighborhood has much to offer, butchered hog is sadly unavailable at the corner bodega. For that I needed to phone Jon Payton, chief curator at Dines Farms, in the Catskills, a purveyor of succulent, pasture-raised livestock. Not only did Payton have what I wanted; he was able to deliver it to my 'hood. The 50-pound beast was a sight to see: precisely half a Wilbur, split down the spine, headless, gleaming, alabaster-white. To inject it with a mojo brineÔÇösugar, salt, water, orange juice, and lime juiceÔÇöI went to a vet and procured a giant syringe. (“You're going to use it to cook a pig?” the vet's assistant asked. “Wait here. I'll get the doctor.”) As I laid the torso across the grate, I couldn't help noticing a distinct resemblance to a Damien Hirst installation.

Seven hours later, the hog was good to go: tail charred, skin caramelized, flesh golden, soft, and sweaty. Hacking it to pieces on my countertop, I saw years of my life pass before my eyes. Still, whatever the damage done to my arteries, it was a trifling price to pay. The pork was so sweet, one dinner guest declared that it tasted like “pig brownie.”

When the table was cleared, I had a moment to ponder. Perhaps the hog roast was a kind of climaxÔÇöthe achievement that would free me from the Kettle's iron grip? I went to bed that night in a blissful state: fat, happy, fully pleasured, seemingly sated. But then the next morning I woke with one thought: Easter, by God, is only nine months away. I wonder if Jon Payton can score me a lamb? ÔÇöJohn Heilemann