Base Camp Confidential

An oral history of Everest's endearingly dysfunctional village

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

This month, some 500 climbers from around the world, along with their support crews and hired Sherpas, will set up camp on a rock-strewn glacier at the foot of 29,035-foot Mount Everest, in the Khumbu region of northeastern Nepal. By all accounts, the strip of moraine that serves as Everest Base Camp is a barren wasteland, capable of sustaining little save the few single-cell creatures and lichens that live on the million-year- old granite. It affords no view of the upper section of the mountain that weighs so heavily on the minds of the many climbers who venture there. But twice each year, in the spring and the fall, this barren slag heap gives rise to a thriving ripstop metropolis, home to several hundred Sherpas, the native people of the Khumbu region, as well as an elite mountaineering citizenry who can afford the permits and equipment necessary to scale the monolith.

Like any city, Everest Base Camp has its own social structure, an astonishing collection of amenities, and just as many problems. It even has an official waste-removal staff that empties dozens of latrines on a regular basis. With pulses quickening in anticipation of clear skies and a chance to make the summit, ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° decided to take a look back at the history of this little village at the top of the world. What follows is a catalog of recollections, edited for length and clarity, as told by the hardy individuals who've made it their home over the last 48 years.

Modern Base Camp is a far cry from the solemn, holy ground where Sherpa Tenzing Norgay and New Zealander Edmund Hillary launched their historic bid for the summit in the name of the British Crown in 1953. At that time, very few Westerners had laid eyes on the mountain's southern, or Nepalese, side. The British had made several attempts to climb Everest via the Tibetan side as far back as the early 1920s, but the Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1950 closed off the north to foreign expeditions until the late seventies. When Hillary and Tenzing showed up, only three years after the Kingdom of Nepal opened the southern routes to mountaineers, they came with an army of over 350 porters, 20 climbing Sherpas, and 14 Westerners.

SIR EDMUND HILLARY: We were the only expedition on the mountain in 1953. Of course, the base camp we used is not the Base Camp where everybody goes now. We were rather closer to the bottom of the Icefall. There were lots of ice pinnacles and plenty of loose rocks lying around. It was not a comfortable place by any means for camping, but we had a magnificent view at the bottom of the Icefall and up toward the summit. I didn't regard it as a particularly special place. It was like all base camps: It had piles of equipment and food and climbing gear. I don't remember doing a great deal of relaxing there.

In those days, the expedition members worked hard. We helped carry loads up with the Sherpas. Nowadays, the Sherpas do most of the work and the expedition members sit around a great deal. We did not sit around. We were constantly sorting loads, carrying loads. We very quickly discovered which of the containers held the better food…so toward the end we had all the food that wasn't all that popular. We had some potatoes there, and tinned meat. But it wasn't very exciting, our food, I can assure you.

In the decade following Hillary's climb, seven other people from two teams, Swiss and Chinese, managed to reach the top. It wasn't until 1963 that an American teamÔÇöJim Whittaker, Luther Jerstad, Barry Bishop, Willi Unsoeld, Norman Dyhrenfurth, and Tom HornbeinÔÇöarrived in Base Camp for a first attempt at Everest. The ascent almost didn't happen. On March 23, two days after arriving, team member John “Jake” Breitenbach was crushed by a falling wall of ice. Breitenbach was the first to die on the shifting Khumbu Icefall, a much-feared place that would claim at least 17 more lives over the next 38 years.

JIM WHITTAKER, first American to summit Mount Everest: It was a hell of a walk to Base CampÔÇö185 miles. We moved in with quite an army. Nineteen Americans, 37 Sherpas, 907 porters. We were in fantastic shape when we got there; it took almost a month to get in. The place was empty, with a foot and a half of new snow. Everything was as nature intended it to be.

TOM HORNBEIN, who with Willi Unsoeld summited via the perilous West Ridge route that year and completed the first traverse of the mountain: Hmmm, it was a little intimidating, with these big walls around, peeling off stuff that fell down, and then just a mass of rubble that became our home. And then you're looking right into the jaws of the Icefall, and at first encounter that all seems a little bit frightening. I think the first impulse [after Breitenbach's death] was, The game isn't worth killing people, but there was a lot committed, and the idea of turning this whole behemoth around, with all the support that people had put into it in the way of money and expectations, it didn't seem very feasible. And then there was the rationalizationÔÇöprobably not unreasonableÔÇöthat Jake would not have wished the whole thing to be aborted.

JIM WHITTAKER: [After reaching the summit on May 1], I thought, OK, you made it, but now you've got to get back down. We fought our way down. We had high winds. It was a hell of a climb, and our faces were frostbitten. We got into Camp II and I soaked my feet to get the blackness out of the toes. I'm thinking, I've captured this jewel off the summit, but now I've got to live to tell about it. We raced through the IcefallÔÇöjust shot through that damn thing. Finally we got down to the solid rock of Base Camp. And it was like coming down into spring. Jesus, it was just incredible. I lay in the sun and did a few push-ups. Oh, GodÔÇöand eat like a horse! I was just skinny as hell. It was like being born again. My first meal was Spam. And dill pickles. And they'd saved a Rainier beer for me. They were a sponsor.

With the traditional Southeast Ridge route already conquered, climbers, especially British climbers, began looking for new, difficult, and more aesthetically pleasing routes to the top. By the 1970s many expeditions had done away with huge, militaristic assaults in favor of smaller, lighter expeditions. Base Camp became a tad more homey in the process, but after 20 years of human traffic, the surrounding glacier was beginning to show signs of environmental decay.

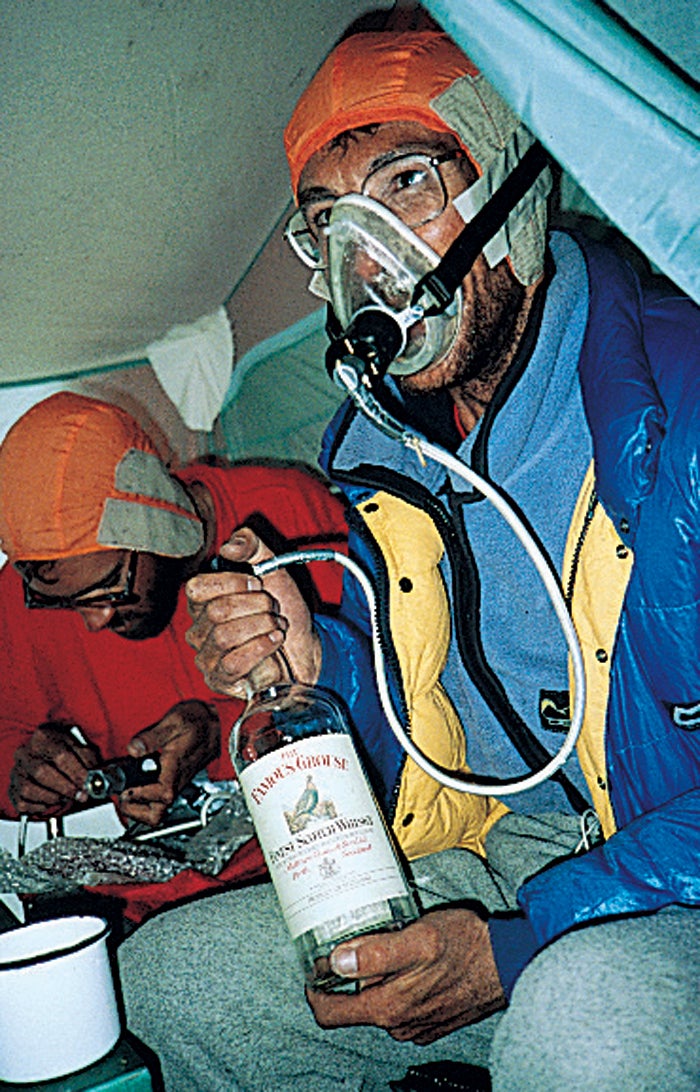

SIR CHRISTIAN BONINGTON, British climber and author, ne plus ultra of Himalayan expedition leaders, who has climbed on Everest four times and summited once: I think what people don't understand about expeditions is how comfortable you can make yourself. And how much leisure there actually is. All you really need is a tent to call home, a good thermos, a good down sleeping bag, and a good down jacket. And a deck of cards. Indeed, we played a lot of very good poker there, high-low straight, brilliant game. And of course we had scotch. I think a bit of alcohol is absolutely essential at Base Camp. You spend a good deal of time sitting around doing nothing.

DOUG SCOTT, free-spirited British climber who in 1975 with Dougal Haston became the first to climb the brutal Southwest Face: At the time, Base Camp wasn't the rubbish heap that it later became. But there definitely was a disturbing trend going on. In those days there wasn't a great deal of thought given to environmental matters, such as deforestation. Almost every other day you'd see a long line of yaks bringing stacks of juniper wood up from the valley for our cooking fires. You know how long juniper takes to grow? Over the years, climbers contributed significantly to the stripping of juniper from the surrounding valleys and crags, till there was almost none left.

PETER HACKETT, Base Camp physician emeritus, who became a leading authority on high-altitude health and medicine over the course of three decades of Everest expeditions: Back in the seventies there were doctors who really didn't know what the heck they were doing. Probably the most dramatic case was a Swiss physician who signed up to be an expedition doctor because he had just broken up with his girlfriend and he wanted to take an interesting trip. But he didn't know anything about altitude. I briefed him in Kathmandu all about altitude illness so he'd know what to look for. The next time I saw him, he was in a deep coma. His last words were, “I think I have cerebral edema.”

DOUG SCOTT: It was like camping in the bottom of a quarry, really. I mean, it had its moments. When we climbed the Southwest Face, Dougal Haston and I returned from the summit very late, only to realize as the days went by that [our fellow climber] Mick Burke wasn't going to come back, that he somehow disappeared around the summit area. That was bad business.

Perhaps no expedition has been touted for boldness like Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler's 1978 summit of Everest without supplemental oxygen.

REINHOLD MESSNER, Italian Tyrolean climber considered by many of his peers to be the greatest alpinist of the modern era; in 1980, he completed the first solo climb of Everest via the North Face: Everest Base Camp in '78 was a cloudy, quiet, dirty place. It was dirty from many, many expeditionsÔÇö25 years of Everest ascents. But it was acceptable. We were a dozen climbers, another dozen Sherpas, and half a dozen Base Camp staffÔÇökitchen and so on. During the period we were there, there were more or less 32 trekkers who came to visit. They came for one hour, and then left. In my view this was the maximum the glacier could support. [Since then] I know there come 500 to 600 people in one season. Now it's a totally different thing. I was reading and writing and sitting together with the others and going to the mess tent. I did not do any strategizing. I will never do an expedition which I cannot write out or design on one piece of paper. It's a tragedy now at camp with all the computers there. It's like a huge factory. You don't need it. You need nothing for climbing EverestÔÇösurely not a computer.

Despite the increased climbing traffic, Everest remained a solitary place into the early 1980s, with just one team occupying Base Camp per season. That changed, in sometimes startlingly cushy ways, in 1983, when the Nepalese government opened up the mountain to five teams per season, each on a different route. Base Camp metamorphosed into a bustling international village, with a rudimentary media operation, better heating, and the occasional prize ham.

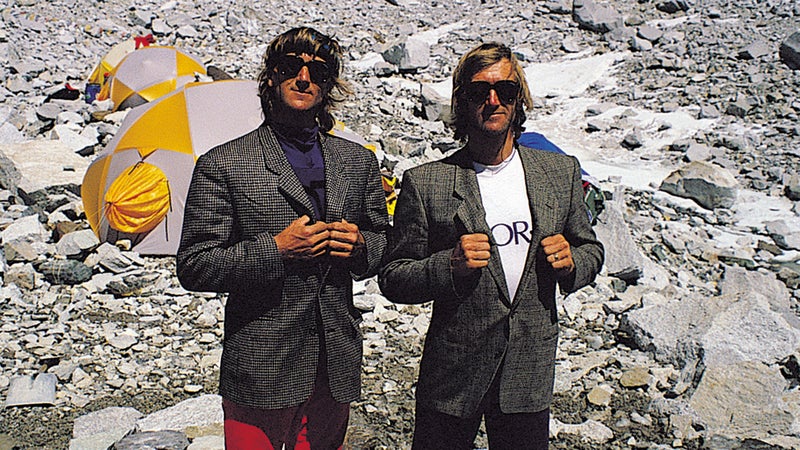

AL BURGESS, member of the British West Ridge Expedition in 1980 and one-half of the notorious Burgess Twins, whose style pushed the limits both on the mountain and at Base Camp social gatherings: It was winter. There was no fresh snow. It was just a glacial moraine on top of dry ice. We were cooking with kerosene, and I remember the kerosene freezing. It was minus 30 every day. We just hung around in full down suits, and there was no running water anywhere. Nobody really knew what giardia was. Even our doctor didn't know. Our stomachs were just riddled. We didn't have filter pumps or iodizing. We were swallowing antibiotics like candy.

KURT DIEMBERGER, Austrian cinematographer and grandfather of the fast-and-light approach to climbing in the Himalayas: Ah, we had fabulous food. At Base Camp you must always eat to keep your body weight up. I remember the Italians, they had a tent full of hams, hams big like a guitar, hanging there in two rows. The Spanish even beat the Italians. They had the best food I have ever had in my life. They had big hams, lots of hams, and they brought lots of tomato juice and big bags full of garlic, which they bought in the villages, ja? One year we had freeze-dried food, but we all got the shits, ja? People at Base Camp would often get the shits. Every year the expedition leader set a rule. He says, “OK, we agree. We take the water for the kitchen from the left side of the moraine and everybody goes to shit on the right side of the moraine.” But nobody ever remembers what the orders were the following year. It could be just the reverse, ja?

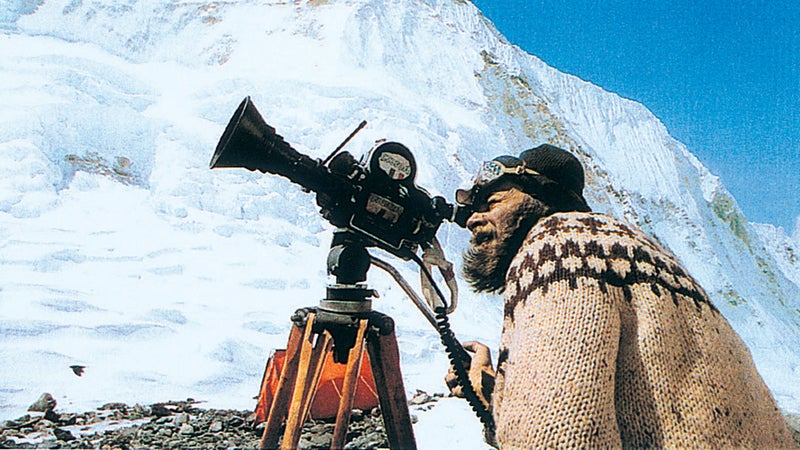

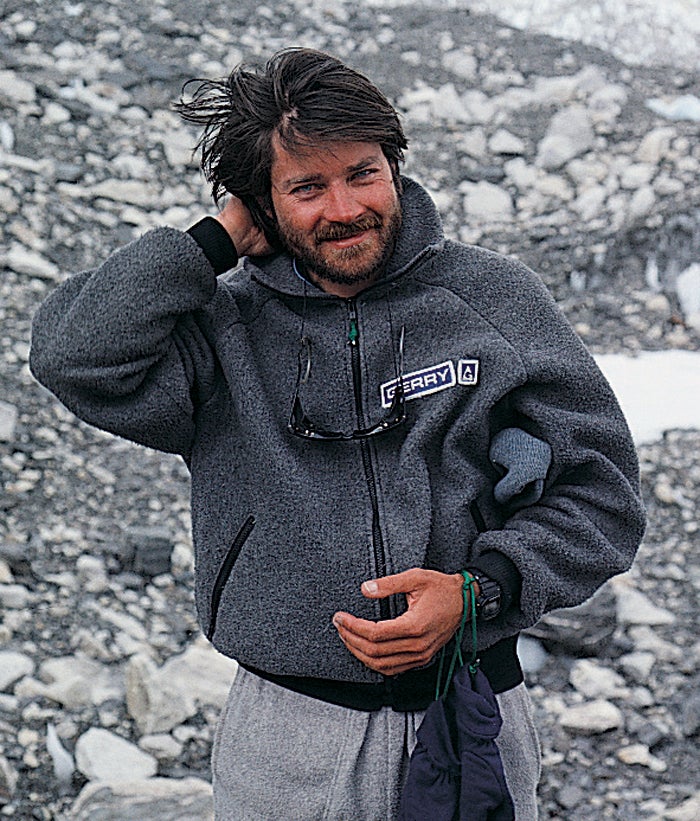

RICK RIDGEWAY, American climber and filmmaker who covered Texas oil tycoon Dick Bass's summit attempt in 1983 for Bass didn't make it to the top, but David Breashears, working as a cameraman for ABC, did: That one was a different expedition for everybody. I was a producer for ABC and at the same time I was the correspondent, so I had a microphone that had the ABC logo on it, and I had an ABC patch that I was supposed to pin on my jacket and stand in front of the camera and file reports and do interviews as those guys went up the mountain. We had this young hotshot named David Breashears rope-gun the camera to the summit. He microwaved the signal off the top to a receiver dish on top of the Everest View Hotel [in the Khumbu Valley] and then it was transmitted to Kathmandu and then to New York. It was the first live transmission off the summit. Kind of neat.

PETE ATHANS, consummate American guide known to his peers as “Mr. Everest” for taking part in 13 expeditions up the mountain: Boy, it's ironic, because my first experience at Base Camp was extremely negative. In 1985 there was really no environmental ethic. There were still huge piles of trash that were just smoldering up there. We did have contact via shortwave radio to the [Nepalese] Ministry of Tourism, but it was incredibly unreliable. Occasionally it would work wellÔÇöwhen everyone's antennas were lined up and the god Vishnu was smiling on everybody. It was almost a comedy. We'd run wires all over the place and put tinfoil on 'em and do the best we could to try to get the weather forecasts.

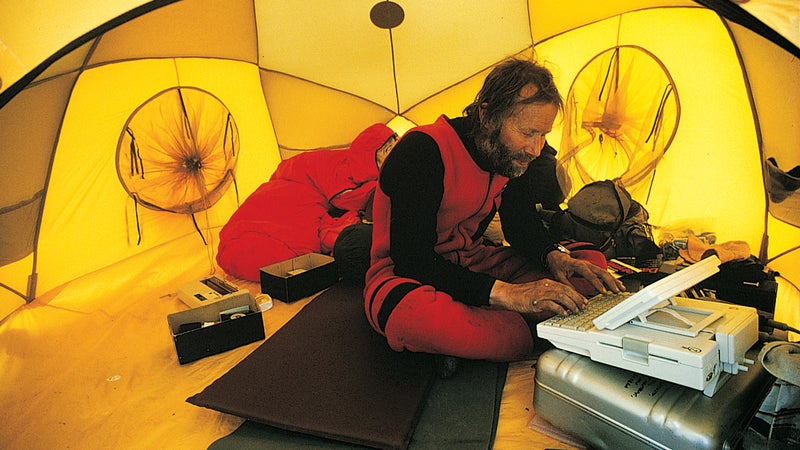

ED WEBSTER, American climber, writer, and photographer who lost eight fingertips and three toes to frostbite on Everest: [In 1985] we had a propane space heater for our dining tent. We called it the “wuss machine.” Everybody wanted to sit next to the wuss machine in the mess tent to warm up in the evenings. That was basically the only luxury item in the camp. Although Chris Bonington did have an Apple IIc computer, we had one tooÔÇöprobably one of the first years a computer had been to Base Camp, I think. We had solar-powered battery rechargers. Our journalists would type their dispatches on the computer, print 'em out, and then they would be sent by mail runner down the trail.

PETER HACKETT: I had my share of drama, but a lot of what I saw in Base Camp was pretty routine. A lot of headaches, from both the altitude and the occasional hangover. Lots of broken ribs caused by incessant coughing. I'd say that codeine was the wonder drug at Base CampÔÇöand still is. It kills the headache, stops up your bowelsÔÇöwhich climbers like when they're on the mountainÔÇöand stops your cough. A few times we had climbers whose blood had thickened too much. We'd treat it by bleeding off a bunch of blood. All I needed was a flat place for the climber to lie down, and then I'd stick a big needle in his arm. Basically, I'd run a small tube out of the body and into an empty tin can. We'd bleed off about a pint at a time. The Sherpas thought it was really crazy, because they thought of the blood as a source of strength. They wouldn't allow their own blood to be drawn, and they didn't want to deal with anybody else's blood either. So I'd have to go empty it away from Base Camp, just sort of hide it from the Sherpas, behind a rock. You can imagine, the Sherpas coming over to my place for tea, and there's this climber there with blood pouring out of him.

In 1987 Nepal opened Everest up even more, allowing multiple permits on routes. The number of climbers swelled from about 100 annually to 500, and Base Camp faced a new problem: urban sprawl. The 1988 season also saw a series of other firsts: the fastest summit, in 22 hours, by Frenchman Marc Batard; the first person to parapente from the summit, Frenchman Jean-Marc Boivin; the first American woman on top, Stacy Allison; and the first woman to summit without oxygen, New Zealander Lydia Bradey.

STACY ALLISON: The size of Base Camp kind of hit me smack in the face. It's like, “My God, Everest is a big mountain, but can it accommodate so many people at the same time?” But back then people weren't taking their computers, their cell phones, their weather stations. We were there to climb. There weren't all these other agendas going on. When the girls and I had free time, we went over to the other side of the glacier and did our toenails. And gossiped. Very simple pleasures.

GEOFF TABIN, zany American climber and ophthalmologist who has completed the Seven Summits: It was a small Base Camp and virtually everyone was a character [in 1988]. There was Marc Batard, who was this Napoleonic figure, about five-foot-six, very skinny. This was in the days before titanium became well known. He was going to do this speed ascent and he had titanium crampons and a titanium ice ax, and a one-piece suit with this bladder which held, like, two and a half liters of black coffee. And then Jean-Marc Boivin, who [was going to] jump from the summit with a parapente. He was your basic French cool personified. Everything he had had the logo “Jean-Marc Boivin Extreme Dream Team.” He jumped and landed down at Camp II in 11 minutes. Unfortunately, he died two years later BASE jumping Angel Falls.

We had a guy on our team named Johnny Petroske [who] took a big blue-and-white barrel and painted red stars on it, and lined the inside with toilet paper. He brought it over to the French television crew and started telling them about how he started out barrel-rolling on Mount Rainier, and then Niagara Falls and Mount McKinley, and now he was going to barrel-roll from the summit of Everest. Whenever they asked him why he was doing this, he would go, “IT IS MY DESTINY!”

Lydia Bradey was an incredible person…kinda laid back, hard climbing. She had the most unbelievably killer body. She wore this skin-tight Lycra suit around Base Camp. She had absolutely flash white teeth, really sparkling eyes, and blond dreadlocks. A lively, wisecracking, good spirit. She was a little bit of a wild woman. Lydia had this summit suit designed to make it easier for women to pee out of, but we joked that it also gave easy access for other activities. She ended up climbing solo up the mountain after a feud with her teammates. Lydia came down a heroine. [She] came down and said, “I made it to the summit of Everest.” Everyone said, “Hey, congratulations!”

KAREN FELLERHOFF, American expedition organizer in the late eighties: ShoSho was my dog that followed the yak trains up to Everest Base Camp in the spring of 1989. I think he survived on a diet of yak manure. He appeared under the flap of my team's dining tent our first night at Base Camp. He was covered in the little yellow and brown dags he acquired sleeping in the rock latrines. I fed him Vienna sausages and disinfected him with surgical soap purloined from the hospital tent. ShoSho is Sherpa for “come here.” He had a stash of bones he hoarded near my tent. He enjoyed the sunny part of the day gnawing on a good rib. I was curious. Barbecue spareribs were not on the menu at Base Camp. One morning I followed him on his daily trek through the pinnacles and discovered the source of his bones. It was a mummified, shrunken climber wrapped in a sun-bleached tent. The poor fellow had probably been laid to rest in a crevasse 20 years earlier and spit out by the glacier that spring. I gathered the bones from ShoSho's cache and folded the rest of the remains in a cloth and cast them in a crevasse.

By the 1990s, Base Camp social life no longer consisted of playing cards and having a nip of scotch. With tents full of adrenaline-soaked residents waiting for the weather to clear, the boredom often got too strong to bear sober. Or alone.

BRENT BISHOP, son of 1963 American team member Barry Bishop and leader of several environmental cleanup expeditions to Everest in the nineties: There's a lot of debauchery in Base Camp. You've got the yak train coming up, so there's always beer or chang to be consumed. You have good food. You have sat phones. You have computers. There's rock-n-roll music. There's hash to be smoked, if your lungs can take it. Hey, it's a big party. Anybody in the outside world who thinks you're suffering is delusional. Don't you realize what's going on here? It's very colonial. You've got a staff, for God's sake. Even if you want to work, the Sherpa staff won't let you. You might be a low-life climber back home in the U.S., but once you get to Base Camp you're catered to. You get there and take a look around and it's like, “We're kings at Base Camp!”

ADRIAN BURGESS, the other half of the notorious Burgess twins: There's enough hardship on an expedition. You don't want people dreaming of steak and salads and stuff. And beer. I've always believed that if you can quench some of these dreams, you can keep your teammates focused on the mountain.

AL BURGESS: So me twin brother and I always brewed a good English ale in Base Camp. It was too cold, so we didn't get much fizz, but it wasn't bad.

ADRIAN BURGESS: We had some parties with it, that's for sure. But oh, GodÔÇöthe hangovers! They're quite annihilating. You feel like you've slept at 26,000 feet.

ED VIESTURS, famously strong climber and guide, and an almost constant presence at Everest since 1987: I remember this buddy of mine made it halfway into his tent. He just passed out. He woke up the next day with his legs still laying outside, and he thought his feet were nearly frostbitten.

TODD BURLESON, founder and director of Alpine Ascents International, one of the first guide outfits to offer trips up the mountain: The Sherpas like to have quite a party. When they start drinking… I remember one year we literally had a stretcher to carry Sherpas who had passed out in the snow. And then you'd get these Sherpa fights. Some porter would call one of our Sherpas, you know, a high-altitude dork or something, and this guy would rip his shirt off, and 20 of them would get into it. We had some good times that way.

HENRY TODD, Scottish expedition organizer and perennial figure in Base Camp throughout the 1990s: One of the very best parties was when [expedition leader] Mal Duff died in Base Camp [in 1997]. He was a great raconteur and we were having a very serious wake. Mal was Scottish. After we did our bit of talking, we were singing the Scottish national anthem, and the only two people who knew the words were myself and Pete Athans. But after we repeated it a couple of times, everyone knew it. Just about everyone had brought a bottle of whiskey. And in no time at all it got very, very wild. We went back to Jon Tinker's mess tent and Guy Cotter has this amazing act that he can do; he can swing like a chimpanzee from rafter to rafter. Tinker's tent had these rafters, and so we had Cotter going up and down and up, up above a table absolutely littered with glass. If he had fallen, which looked to be incredibly probable, he would have smashed himself and all that glass.

NEAL BEIDLEMAN, American guide and climber, best known for saving several lives during the deadly 1996 storm on Everest: You know, it used to be information that was the most coveted item from the real world. Now the big thing everybody craves is young female climbers. No price can be put on their worth to the lecherous, tongue-dragging, testosterone-riddled male climbers.

LYDIA BRADEY: We females would take my little stereo and go to the other side of the moraine to where we were really private. And we found this big flat rock and we used to go dancing to the techno-pop of the late eighties. We just loved dancing. That was our retreat, really. We did a lot of dancing or talking, or I guess a little bit of smoking or drinking. It was quite funny. Good way to acclimatize.

AL BURGESS: I really can't tell you some of the stories because, you know, some people are married. Of course, the Sherpas always knew who was sleeping with whom. I'm certainly not putting any names to this story, but I've heard of climbers leaving girls' tents in the middle of the night and walking backwards between tents so the tracks in the snow confuse the nosy people in Base Camp. That's a pretty common trick.

HEIDI HOWKINS, American climber and expedition organizer who attempted the summit in 1999: It's not a difficult thing to pull off, even up higher on the mountain, as long as you have supplementary oxygen. I mean, you've got down sleeping bags and down suits. And the confines of the tent is no big deal. It's more the… uh…can you do it? I'm pretty sure I know who holds the altitude record now. I'm not saying. But let's just say this couple made it happen at the South Col, at 26,200 feet.

ADRIAN BURGESS: You know, whenever you've got a few women in a dangerous situation, you better look out. Death and sex are very closely linked, right? That's what Freud reckoned. So it never surprised me when people started having it off in dangerous situations.

G├ľRAN KROPP, unorthodox adventurer who rode his bike from Sweden to Everest in 1996 and summited: I heard a lot of rumors about sex in Base Camp, but I was not invited. Yes, I have felt the glacier moving. [Laughs] That was a bad joke.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, crime increased at 17,500 feet. Often it took the form of small-time thievery, requiring locks on many tent-door zippers, but there were some brutal assaults.

STACY ALLISON: [In 1988] we actually had to kick a Sherpa out of Base Camp. He had become very difficult. And he got very mad at the Korean leader, pulled a knife on him. We had to restrain him, tie him up. Isn't that awful? We weren't sure what he was going to do if we let him go. Ultimately, he was escorted down off Base Camp.

HEIDI HOWKINS: Violence is not unusual. Some people say it's because climbers' personalities tend to be deviant. I don't think it's just that. I think it's also because the process of acclimatization, of generating red blood cells, is very hormonal. And it primarily involves estrogen, right, which is the thing that upsets women's attitudes and psychology every month. I always approach Base Camp with the attitude: OK, here's 300 men who have PMS and really don't know what's going on. And then it all makes sense.

TODD BURLESON: One year these Russians were in camp, and everybody seemed to be climbing illegally. One of the cooks got really mad about that and he picked up a huge boulder and smacked it on top of the leader's head. And so he's laying there unconscious, and this guy is about to finish him off when Pete [Athans] jumped him from behind and tied him up. The Russians wanted justice for this attack, they wanted to send him to jail. But we came in with our own version of high-altitude justice. We decided that the punishment for climbing illegally was getting smacked in the head with a rock.

The 1990s saw the biggest increase in the number of commercially guided trips. No longer did you have to be an experienced mountaineer with dozens of Himalayan peaks on your r├ęsum├ę. All you needed to get a spot on a team was a pulseÔÇöand $64,000. The unexpected consequence was a simultaneous increase in high-altitude rubberneckers yearning to mingle with Everest's glamorous new media darlings.

JEFF RHOADS, American climber and cinematographer who in 1998 became the first non-Sherpa to summit twice in one season: You get a lot of random people just walking through camp, and the climbers get a little bummed. Climbers don't want to have anything to do with the trekkers; they're afraid they're going to get sick. A couple years ago, two guys came walking into Base Camp carrying bikes. Their plan was to bike to Everest. So these dudes were like, “God, we don't have any food, could you give us a cup of tea?” And you know what? We were doing our own thing right then. We said, like, “No, we can't. See you guys later.”

NEAL BEIDLEMAN: I've seen some really bizarre trekkers who don't have a friggin' clue. You know the type: The world travelers, the hippies of past years reincarnated. They come cruising in, and they don't have much gear, and they're all happy, and they've got drums or tambourines or whatever, and poof, they get themselves to Base Camp and get ill. They go, “Oh, my God, it's really fucking cold up here,” and you've got to help them out.

G├ľ├ľRAN KROPP: There was a man who was trying to put his son's umbilical cord up on the summit of Everest. I think that was quite amazing. He had been there four times before to try to carry that silly cord up there. And then there was a Russian guy in leopard-skin tights flying a parapente over the Base Camp with his wife hanging below him on a rope, lower down, sometimes hitting the rocks. That was also crazy.

PETER HILLARY, son of Edmund and veteran Himalayan climber: We established the Royal Khumbu Angling Association and Men's FellowshipÔÇöa pseudo fishing club at 17,500 feet. It was a lot of fun. We had fixed lines going out to frozen pools on the glacier. I remember trekkers coming up and they'd say, “What on earth are these ropes for?” And I'd just say, “Fishing lines. Ah, you should have been here this morning. The fish were biting. They were absolutely delicious. We had them for breakfast.” I'm pretty sure the poor trekkers thought we must be suffering from cerebral edema. We told them there was a specific species that lived on the glacierÔÇöthe chisel-headed salmon. The chisel-shaped head allowed them to swim through the ice. Ah, yes, the Royal Khumbu Angling Association. Royal in the Nepalese sense, of course. We even had certificates.

NEAL BEIDLEMAN: Even though this is at 17,500 feet and it's in the middle of Nepal, Everest Base Camp is a thriving economic place now. You can get whatever you want, in exchange for money. People know the value of a dollar. You can buy Cokes and beers. You can buy equipment. Crampons. You could pretty much outfit yourself right there.

ED VIESTURS: Boy, the noises are unforgettable. You hear everything: coughing, hawking up a loogey, vomiting. And you've got noisy generators going all day. People yelling into the radios to talk to somebody up on the mountain. They figure if they yell, it will transmit better. Yak bells coming and going as other teams arrive. Satellite phones ringing. And in the morning, at about two or three, you'll hear another team tromping past your tent, heading up into the Icefall. You hear this whole entourageÔÇöyou know, the crampons crunching through the ice and gravelÔÇöfiling by your tent while you're snuggling in your bed thinking, “Ah, I'm kinda glad that's not me today.” But, man, you're also thinking, “I hope whoever is out there is going to have a good dayÔÇöand that they make it back down to Base Camp.“

In 1993 the new record for people on top hit 129. Now the whole world really was watching. But as the successes skyrocketed, so did the tensionÔÇöand the death. The loss of 15 climbers in the spring of 1996 brought the Everest overcrowding debate to fever pitch and led to a lot of soul-searching among Base Camp veterans. But it hasn't stopped them from coming back.

NGIMA KALE SHERPA, cook who worked several years for the late expedition leader Scott Fischer: When we arrive at Base Camp, before the climbing begins, we have to make a puja ceremony to please the gods. People think that Mount Everest is a big rock, but it's not just a rock. We believe that Mount Everest is a god. If you're lot of shitty job doing there, lot of things happen, you know? If a girl and boy stay together in tent, then something bad will happen. Sometimes people will break their legs. Sometimes Sherpas get killed. So what do? We make a little, short tent, which has a flat rock for burning juniper. We bring out all our expedition gear, like crampons and ice axes, and then we bring a couple bottles of chang, and then beer, and then we put all this stuff together with the Sherpa stuff, with the rice and juniper. And then we each other making little celebrating for blessing from the gods, make sure we can have permission to go on the mountain.

NEAL BEIDLEMAN: As people start to go higher, tension in the camps goes from lighthearted to dead serious. People down in Base Camp start wandering around to the other camps that have radios, they start tuning in, and the rumors are flying. And then when people start coming off the mountain, either there's just complete euphoria and joy and happiness shared by the team, or there's complete meltdowns. It really brings out some very, very deep emotions.

AL BURGESS: I don't know why anybody wants to particularly hike there. It's still a physical wasteland. It's ironic, because if you look at Hindu and Buddhist pilgrimage sites, usually they're places where water, air, fire, earth all come together. There's some significance. But the Western shrine is Everest Base Camp. The pilgrimage is like rusted tin cans and strung-out egos.

DAVID BREASHEARS, American climber and filmmaker whose work includes the IMAX film: One night in 1996, several weeks before the tragedy, I went outside my tent around 4 a.m. I just stood there, with the prayer flags flapping in the gentle breeze. There was a pretty good moon, and I could see ice glistening thousands of feet above on the West Shoulder. I could hear the pops, the creaks, the rumbling of the ice underfoot and all around. It reminded me that the place was alive, that it was dangerous, unpredictable. Above the silhouette of the surrounding peaks was the comet Hayakutake. I asked myself, When will this comet come around again, and when did it last come around? I could feel the timelessness of this patch of rock that's Base Camp, the ephemeral nature of our existence. Yes, we're driven by all sorts of different things. We're goal-oriented, we're trophy hunters, we're Walter Mitty types. But when you're on Everest, the basic rhythms of night take over: You eat and you rest. All is quiet. In the morning the sun will come, and all of this ambition and all of this drive and all of the different forces that work on the mountain these days will come to life.