On a recent Tuesday evening in Santa Fe, a handful of people gathered at Collected Works Bookstore to hear read from his new book, . It was one of the first really cold nights of the season and half a dozen members of the audience were clad in sheepskin and down. Tomine, a father of two from Bainbridge Island in Puget Sound, Washington, showed up in standard Pacific Northwest attire: a crinkly, bright blue rain jacket. Every so often, he'd interrupt himself to take a big swig of water and say, “I’ve never felt so dry in my whole life.”

Tomine and his family are avid adventurers, but their sport of choice isn’t climbing or paddling, cycling or surfing. It’s foraging. In all weather and seasons, they take to their motorboat, the local beaches, forests, and trails to hunt for crabs, king salmon, razor clams, chanterelle mushrooms, oysters, and blackberries. Listening to someone describe the outrageous edible bounties of the Pacific Northwest while landlocked in the high desert is a little surreal, to say the least, and the experience was much like that of reading Tomine's book: Saltwater seemed to drip from every word; I could taste the brine in the pages.

The first thing Tomine will tell you is that his family isn't made up of die-hard foraging survivalists. “We’re just a regular suburban family that spends time outside looking for food,” he said. “It’s not like my kids don’t know what Cheetos taste like. We still shop at Costco. We’re not very extreme in any way.” But nor is this a short-term experiment, a one-year trial run in fishing, foraging, and gardening. It’s not a whim. “It’s just how we’ve evolved to live.”

All humans share a latent foraging instinct, Tomine believes, but it’s especially pronounced in kids. “These instincts aren’t dulled and muted in small children like they are in adults,” he explained. “They’re close to the surface. I’m constantly surprised at the levels of patience and aptitude my kids bring to finding their growing food.”

His daughter, Skyla, now nine, has been fishing on Puget Sound since she was two, swaddled in a life vest in their small skiff. In one short chapter entitled “Conversation With a Six Year Old” it’s almost dark when Tomine finds Skyla down at the dock, fishing rod in hand, tiny, three-inch bass on the hook. “Dad … they’re really biting now. Can’t we please stay longer? I want to catch one more….” Tomine obliges. How could he not? Like him, sea air and fish are in his daughter's blood.

Tomine, a Japanese American raised in western Oregon, has been finding his own growing food since he was a boy, foraging mushrooms with his grandparents. He studied creative writing at University of California, Davis, guided at a sport fishing lodge in Alaska for six years, then worked as a copywriter in Seattle before chucking the nine-to-five grind to fish and forage and freelance from his home on Bainbridge Island. “I’ve been a fish bum my whole life. And a gardening bum. And a chanterelle-picking bum.”

All humans share a latent foraging instinct, Tomine believes, but it’s especially pronounced in kids.

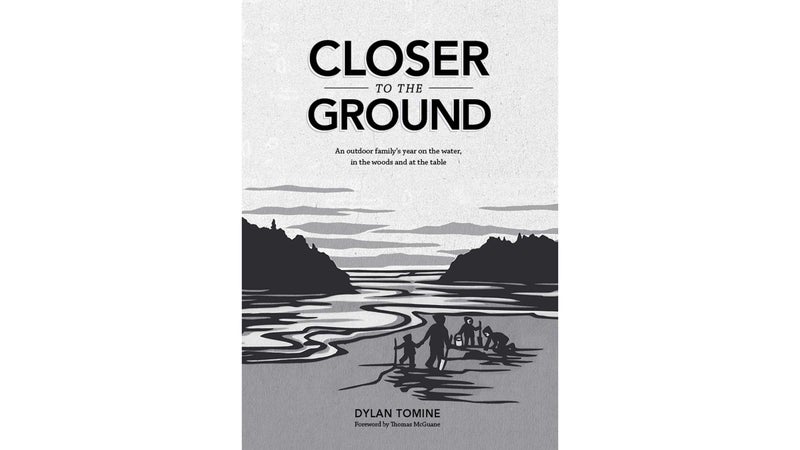

Tomine is too modest to boast, but he's clearly an adept writer, and Closer to the Ground is as understated as its author, a quietly compelling account of four seasons of foraging just out the back door. In Puget Sound, something’s always in season: king salmon, Dungeness crab, razor clams, Christmas crab, wild black huckleberries, dandelion greens, wild thistle. There are multi-family oyster outings, communal seed-planting parties for his wife Stacy’s vegetable garden, and obsessive 23-hour striker missions (sans kids). And lots and lots of cooking and eating. This is some of the most evocative, mouthwatering food writing I’ve ever read. In one particularly tantalizing/tormenting episode, Tomine’s got a gourmet assembly line going in the kitchen, “rich, citrusy amber ale from 7 Seas Brewery down in Gig Harbor” is flowing, and kids—freshly hosed off from the rainy day oyster hunt—are happily underfoot:

“Candace has the big crab pot loaded with clams, butter, garlic, white wine, and parsley. A couple of big crusty loaves from the bakery up in Port Townsend are warming in the oven. Stacy’s tossing winter greens with dried cranberries, sunflower seeds, and vinaigrette…. Using long bamboo chopsticks, I get into a rhythm of lifting, turning, pulling finished oysters out and adding new ones. As each oyster reaches golden perfection, I set it on a rack and drop another one in. I sprinkle the hot oysters with a pinch of kosher salt and slide it into the oven next to the warm bread…. We are getting down to some serious eating now.”

The fresh vegetables from their garden last all summer, and by fall they’ve frozen everything they can’t eat; they’re eating homegrown broccoli all winter. The salmon they catch from July through September is enough to feed them once a week all year. Last year they bought their own blueberry farm, and were knee deep in berries all summer, canning what they couldn’t eat. It’s both old-fashioned and totally of the moment, like a modern-day .

The strength of the book, of course, is that, like Tomine, it leads by example. It’s a paean to eating (and drinking) locally without ever being preachy. A self-taught fisherman and forager, who relied on the generous guidance of outdoor mentors, Tomine doesn’t pass himself off as an expert—even when it comes to his children. “It’s easy to assume that this is a book about what a father teaches his kids about the outdoors,” he told the gathering in Santa Fe, “but we're just learning it all together. This is really about what they teach me.”

After listening to him talk and read about seafood for nearly an hour, there was only one sensible thing to do. I absolutely had to go eat fish—and lots of it—or I might die. Tomine tagged along to a sushi bar down the street, even though he’d eaten there the night before. You can take the fisherman out of Puget Sound but you can’t take Puget Sound out of the fisherman. Over green chile and salmon Santa Fe rolls, he spilled a few of his favorite lessons from the kids:

Encourage Children to Be Part of the Process

“If you want to do more with kids outside, basing it around food is a good strategy. There’s a level of intensity to it for kids if the goal is food, whether it’s fishing or crabbing. But it doesn’t have to be foraging, per se. Kids love to grow carrot seeds in a pot. If they participate in the food process, they’re so much more apt to enjoy eating whatever it is.”

Expose Kids to New Flavors When They're Young

“We protect our kids from strange flavors. You hear about picky eaters—it’s common. I sympathize. But if kids grow up thinking these flavors are normal, they’ll get used to them. My daughter eats the oiliest, fishiest part of the salmon, the collar.”

Establish Ground Rules

“We’re pretty controlling about the wild edible stuff. We have a rule that they have to show us everything before they eat it. We don’t want them just picking it and stuffing it in their mouth.”

Be Prepared, Worry Less

“I worry so much about safety. Before we go, I’ve thought it out from every angle. But there are always worst-case scenarios you can’t predict. On the last day of chanterelle season last year, Weston got stung 37 times by hornets. Then on the first day this fall, he got stung by another. You can’t protect them from all outcomes. I’m a worrywart by nature. I try to figure out the safest best way to go about it. If it’s windy and rough on the water, we don’t go. If the kids are miserable, we go home early. I could easily be overbearing, so I need to manage that and let the kids have the experience. I know myself: I’m never going to not worry enough.”

Give Them Jobs

“Our kids love to participate in every part of the food process: from catching the fish, to cleaning it, to eating it. We put them to work in the kitchen, squeezing lemons, mixing a marinade. It’s the same as being outdoors: you weigh what’s safe and appropriate for them. But you don’t need to convince them to participate. The pride they have in the finished product is so uplifting.”